Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

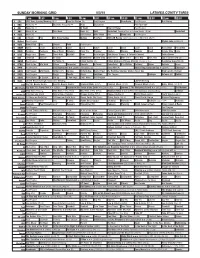

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Index to Academy Oral Histories Leo C. Popkin

Index to Academy Oral Histories Leo C. Popkin Leo C. Popkin (Producer, Director, Exhibitor) Call number: OH142 Academy Award Theater (Los Angeles), 343–344, 354 Academy Awards, 26, 198, 255–256, 329 accounting, 110-111, 371 ACE IN THE HOLE, 326–327 acting, 93, 97, 102, 120–123, 126–130, 138–139, 161, 167–169, 173, 191, 231–234, 249–254, 260–261, 295–297, 337–342, 361–362, 367–368, 374-378, 381–383 Adler, Luther, 260–261, 284 advertising, 102-103, 140–142, 150–151, 194, 223–224 African-Americans and film, 186–190, 195–198, 388-392 African-Americans, depiction of, 111–112, 120–122, 126–130, 142–144, 156–158, 165- 173, 186–189, 199–200, 203, 206–211, 325, 338–351, 357, 388–392 African-American films, 70-214, 390-394 African-Americans in the film industry, 34–36, 43–45, 71–214, 339–341, 351–352, 388- 392 agents, 305-306, 361–362 Ahn, Philip, 251 alcoholism in films, 378 Aliso Theater (Los Angeles), 66 Allied Artists, 89 American Automobile Association (AAA), 315 American Federation of Musicians (Local 47 and Local 767, AFL), 34, 267, 274 American Legion Stadium (Hollywood), 55–56 Anaheim Drive-in Theater (Anaheim), 28, 69 AND THEN THERE WERE NONE, 11-12, 54, 114–120, 166, 224–236, 276, 278, 283, 302–304, 317–318 Anderson, Ernest, 339–341 Anderson, Judith, 226 Anderson, Richard, 382–383 Andriot, Lucien, 226, 230 Angel's Flight railway (Los Angeles), 50 animation, 222 anti-Semitism, 107 Apollo Theater (New York City), 45, 178–179, 352 architecture and film, 366–367 Armstrong, Louis, 133 art direction, 138, 162, 199, 221–222, 226, 264, 269, -

Choreography for the Camera: an Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1992 Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study Vana Patrice Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Vana Patrice, "Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study" (1992). Master's Theses. 894. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/894 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY by Vana Patrice Carter A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1992 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY Vana Patrice Carter, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1992 This study investigates whether a dance choreographer’s lack of knowledge of film, television, or video theory and technology, particularly the capabilities of the camera and montage, restricts choreographic communication via these media. First, several film and television choreographers were surveyed. Second, the literature was analyzed to determine the evolution of dance on film and television (from the choreographers’ perspective). -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Grand Vinyl Weekend! 24-25 October 2020 20 Happening

GRAND VINYL WEEKEND! 24-25 OCTOBER 2020 20 HAPPENING HITS VOL 2 BRANDY SCOTT ENGLISH MOST PEOPLE I KNOW THINK THAT I'M CRAZY BILLY THORPE & THE AZTECS OPEN UP YOUR HEART G WAYNE THOMAS THEME FROM SHAFT ISAAC HAYES LEVON ELTON JOHN COZ I LUV YOU SLADE SHOW ME THE WAY BRIAN CADD/DON MUDIE 1986 WAY TO GO TALK TO ME STEVIE NICKS CHAIN REACTION DIANA ROSS DEATH DEFYING HOO DOO GURUS DISCO DAZZLER EVERY 1'S A WINNER HOT CHOCOLATE BABY HOLD ON EDDIE MONEY IF YOU CAN'T GIVE ME LOVE SUZI QUATRO SUPERSOUND GLAD ALL OVER HUSH GONNA MAKE YOU A STAR DAVID ESSEX BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN WORLD OF MAKE BELIEVE STYLUS FROM THE INSIDE MARCIA HINES ONCE BITTEN TWICE SHY IAN HUNTER TOO MUCH FANDANGO RITZI 1980 THE MUSIC CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE QUEEN TIRED OF TOWING THE LINE ROCKY BURNETTE SAME OLD GIRL DARYL COTTON HOW DO I MAKE YOU LINDA RONSTADT 24 HAPPENING HITS WOMAN YOU'RE BREAKING ME GROOP I THINK WE'RE ALONE NOW TOMMY JAMES & THE SHONDELLS WOMAN WOMAN GARY PUCKETT & UNION GAP 83 THRU THE ROOF BOP GIRL PAT WILSON TELL HER ABOUT IT BILLY JOEL MAXINE SHARON O'NEIL RAIN DRAGON NO SENSE COLD CHISEL SHAKE YOUR TAILFEATHER BLUES BROTHERS/RAY CHARLES KARMA CHAMELEON CULTURE CLUB 20 SOLID HITS ALL RIGHT NOW FREE BAND OF GOLD FREDA PAYNE MR BOJANGLES NITTY GRITTY DIRT BAND YOUR SONG ELTON JOHN CHIRPY CHIRPY CHEEP CHEEP MIDDLE OF THE ROAD SAN BERNADINO CHRISTIE RIPPER HORROR MOVIE SKYHOOKS I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU GARY SHEARSTON DOWN DOWN STATUS QUO NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE GLORIA GAYNOR GIRLS ON THE AVENUE RICHARD CLAPTON IF YOU LOVE ME OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN FREEDOM SHERBET PRIME CUTS ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS INTO THE NIGHT BENNY MARDONES ROCK HARD SUZI QUATRO ACCORDING TO MY HEART THE REELS LITTLE JEANNIE ELTON JOHN FAME IRENE CARA I AM THE BEAT THE LOOK FANTASTIC DANCIN' (ON A SATURDAY NIGHT) BARRY BLUE COME ON FEEL THE NOIZE SLADE STANDING ON THE INSIDE NEIL SEDAKA I REMEMBER WHEN I WAS YOUNG MATT TAYLOR BAND PLAYED THE BOOGIE C.C.S. -

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business.