Re-Diversification of French Hip Hop Through Islam, Gender, and Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT

1 Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média 2Bal 2Neg 3X plus efficacae CD Rap Fr 1996 2 6,80 2pac How do u want it CD Single Hip Hop 1996 1 5,50 2pac Until the end of time CD Single Hip Hop 2001 1 1,30 2pac Until the end of time CD Hip Hop 2001 1 5,99 2 Pac Part 1 THUG CD Digi Hip Hop 2007 1 12 3 eme type Ovnipresent CD Rap Fr 1999 1 20 11’30 contre les lois CD Maxi Rap Fr 1997 1 2,99 racists 44 coups La compil 100% rap nantais CD Rap Fr 1 15 45 Scientific CD Rap Fr 2001 1 14 50 Cent Get Rich or Die Trying CD Hip Hop 2003 1 2,90 50 CENT The new breed CD DVD Hip Hop 2003 1 6 50 Cent The Massacre CD Hip Hop 2005 2 1,90 50 Cent The Massacre CD dvd Hip Hop 2005 1 7,99 50 Cent Curtis CD Hip Hop 2007 1 3,50 50 Cent After Curtis CD Diggi Hip Hop 2007 1 5 50 Cent Self District CD Hip Hop 2009 1 3,50 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 5 Reggaetton 113 Prince de la ville CD Rap Fr 2000 2 4,99 113 Jackpotes 2000 CD Single Rap Fr 2000 1 3,80 2 113 Tonton du bled CD Rap Fr 2000 1 0,99 113 Dans l’urgence CD Rap Fr 2003 1 3,90 113 Degrès CD Rap Fr 2005 1 4,99 113 Un jour de paix CD Rap Fr 2006 1 2,99 113 Illegal Radio CD Rap Fr 2006 1 3,49 113 Universel CD Rap Fr 2010 1 5,99 1995 La suite CD Rap Fr 1995 1 9,40 Aaliyah One In A Million CD Hip Hop 1996 1 9 Aaliyah I refuse & more than a CD single RNB 2001 1 8 woman Aaliyah feat Timbaland We need a resolution CD Single -

Resituating Culture

Resituating culture edited by Gavan Titley Directorate of Youth and Sport Council of Europe Publishing This publication is an edited collection of articles from the resituating culture seminar organised in the framework of the partnership agreement on youth research between the Directorate of Youth and Sport of the Council of Europe and the Directorate-General for Education and Culture, Directorate D, Unit 1, Youth, of the European Commission. The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not neces- sarily reflect the official position of the Council of Europe. All correspondence relating to this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to: Directorate of Youth and Sport European Youth Centre Council of Europe 30, rue Pierre de Coubertin F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex Tel: +33 (0) 3 88 41 23 00 Fax: +33 (0) 3 88 41 27 77 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.coe.int/youth All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc.) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the Publishing Division, Communication and Research Directorate. Cover: Graphic Design Publicis Koufra Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex ISBN 92-871-5396-5 © Council of Europe, April 2004 Reprinted May 2005 Printed at the Council of Europe Contents Pags List of contributors ........................................................................................... 5 Resituating culture: an introduction Gavan Titley ...................................................................................................... 9 Part l. Connexity and self 1. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

L'expression Musicale De Musulmans Européens. Création De Sonorités Et

Revue européenne des migrations internationales vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009 Créations en migrations L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse The Musical Expression of European Muslims. Creation of Tones in the Event of the Religious Norms La expresión musical de musulmanes europeos. Creación de sonoridades a la luz de las normas religiosas Farid El Asri Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 DOI : 10.4000/remi.4946 ISSN : 1777-5418 Éditeur Université de Poitiers Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2009 Pagination : 35-50 ISBN : 978-2-911627-52-1 ISSN : 0765-0752 Référence électronique Farid El Asri, « L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse », Revue européenne des migrations internationales [En ligne], vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 octobre 2012, consulté le 17 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.4946 © Université de Poitiers Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 2009 (25) 2 pp. 35-50 35 L’expression musicale de musulmans européens Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse Farid EL ASRI* La présence musulmane en Europe est, pour une grande partie, originellement issue de l’immigration (Göle, 2005 ; Modood, Triandafyllidou, Zapata-Barrero, 2006 ; Nielsen, 1984 ; Nielsen, 1995 ; Parsons et Smeeding, 2006). Cette présence est également alimentée par des conversions à l’islam1 (Alliévi, 1998 ; Alliévi, 1999 ; Alliévi and Robert Schuman Centre, 2000 ; Minet, 2007 ; Rocher et Cherqaoui, 1986). Ses origines ne sont certainement pas monolithiques. Elle est originaire de nombreuses aires culturelles musul- manes. -

Rap and Islam in France: Arabic Religious Language Contact with Vernacular French Benjamin Hebblethwaite [email protected]

Rap and Islam in France: Arabic Religious Language Contact with Vernacular French Benjamin Hebblethwaite [email protected] 1. Context 2. Data & methods 3. Results 4. Analysis Kamelancien My research orientation: The intersection of Language, Religion and Music Linguistics French-Arabic • Interdisciplinary (language contact • Multilingual & sociolinguistics) • Multicultural • Multi-sensorial Ethnomusicology • Contemporary (rap lyrics) Religion This is a dynamic approach that links (Islam) language, culture and religion. These are core aspects of our humanity. Much of my work focuses on Haitian Vodou music. --La fin du monde by N.A.P. (1998) and Mauvais Oeil by Lunatic (2000) are considered breakthrough albums for lyrics that draw from the Arabic-Islamic lexical field. Since (2001) many artists have drawn from the Islamic lexical field in their raps. Kaotik, Paris, 2011, photo by Ben H. --One of the main causes for borrowing: the internationalization of the language setting in urban areas due to immigration (Calvet 1995:38). This project began with questions about the Arabic Islamic words and expressions used on recordings by French rappers from cities like Paris, Marseille, Le Havre, Lille, Strasbourg, and others. At first I was surprised by these borrowings and I wanted to find out how extensive this lexicon --North Africans are the main sources of Arabic inwas urban in rap France. and how well-known --Sub-Saharan Africans are also involved in disseminatingit is outside the of religiousrap. lexical field that is my focus. The Polemical Republic 2 recent polemics have attacked rap music • Cardet (2013) accuses rap of being a black and Arab hedonism that substitutes for political radicalism. -

Champ Lexical De La Religion Dans Les Chansons De Rap Français

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav románských jazyků a literatur Francouzský jazyk a literatura Champ lexical de la religion dans les chansons de rap français Bakalářská diplomová práce Jakub Slavík Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Alena Polická, Ph.D. Brno 2020 2 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. Zároveň prohlašuji, že se elektronická verze shoduje s verzí tištěnou. V Brně dne ………………… ………………………………… Jakub Slavík 3 Nous tenons à remercier Madame Alena Polická, directrice de notre mémoire, à la fois pour ses conseils précieux et pour le temps qu’elle a bien voulu nous consacrer durant l’élaboration de ce mémoire. Par la suite, nous aimerions également remercier chacun qui a contribué de quelque façon à l’accomplissement de notre travail. 4 Table des matières Introduction ......................................................................................................... 6 1. Partie théorique ............................................................................................. 10 1.1. Le lexique religieux : jalons théoriques ................................................................... 10 1.1.1. La notion de champ lexical ..................................................................................... 11 1.1.2. Le lexique de la religion ......................................................................................... 15 1.1.3. L’orthographe du lexique lié à la religion .............................................................. -

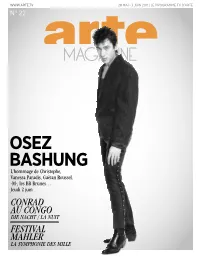

Osez Bashung

WWW.Arte.tv 28 MAI › 3 JUIN 2011 | LE PROGRAMME TV D’ARTE N° 22 OSEZ BASHUNG L’hommage de Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, Gaëtan Roussel, -M-, les BB Brunes… Jeudi 2 juin CONRAD AU CONGO DIE NacHT / LA NUIT FESTIVAL MAHLER LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE ARTE LIVE WEB ARTE LIVE WEB PARTENAIRE DU FESTIVAL DE FÈS MUSIQUES SaCRÉES DU MONDE DU 3 AU 12 JUIN 2011 Ben Harper, Youssou Ndour, Abd Al Malik, Maria Bethânia... Retrouvez les concerts sur arteliveweb.com LES GRANDS RENDEZ-VOUS SAMEDI 28 MAI › VENDREDI 3 JUIN 2011 “Ainsi pénétrions- nous plus avant chaque jour au cœur des ténèbres.” Joseph Conrad dans Die Nacht / La Nuit, mardi 31 mai à 0.50 Lire pages 6-7 et 19 SOULOY / GAMMA BASHUNG Une évocation inspirée du chanteur de “La nuit je mens”, à travers les voix de l’album hommage Tels - Alain Bashung : Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, -M-, Gaëtan Roussel, les BB Brunes... Jeudi 2 juin à 22.20 Lire pages 4-5 et 23 LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE DIRIGÉE PAR RICCARDO CHAILLY Pour le concert de clôture du Festival Mahler de Leipzig, Riccardo Chailly ILS SE MARIÈRENT dirige la Symphonie n° 8 du composi- PATHÉ teur disparu il y a tout juste cent ans. ET EURENT BEAUCOUP Dimanche 29 mai à 18.15 Lire page 12 D’ENFANTS La crise de la quarantaine perturbe le quotidien de Vin- cent et Gabrielle, tout comme celui de leurs amis. Une comédie d’Yvan Attal drôle et touchante qui vous cueille sans prévenir. Avec Charlotte Gainsbourg, lumineuse. Jeudi 2 juin à 20.40 Lire page 22 N° 22 – Semaine du 28 mai au 3 juin 2011 – ARTE Magazine 3 EN COUVErtURE ARÈME C UDOVIC L BASHUNG PAR LES BB BRUNES C’est l’une des plus belles promesses de la scène rock française. -

Cultural Centre Will Host the Francofolies Festival

FRI SUN TJIBAOU 08>10 CULTURAL sept. 2017 CENTRE SAT SUN NC 1 ÈRE 09>10 FRANCOFOLIES sept. 2017 VILLAGE press release Press relations Fany Torre Tél : (+687) 74 08 06 @ : [email protected] Organisation Stéphanie Habasque-Tobie Chris Tatéossian Tél : (+687) 74 80 03 Tél : (+687) 84 37 12 @ : [email protected] @ : [email protected] MusiCAL Productions 1 ST EDITION OF THE Francofolies Festival in New Caledonia From the 8th to the 10th of September 2017, the Tjibaou Cultural Centre will host the Francofolies Festival. Three days of partying, French language music and numerous local and international artists of renown are expected. Parallel to these concerts, on Sunday, 9th and Sunday, 10th of September, the “NC 1ère Village of the Francofolies” will be dedicated to the Caledonian scene. It will also be a place where the public can meet international artists. At the Tjibaou cultural centre days of Caledonian artists or bands on stage 3 concerts 6 before the international artists NC 1ère Festival Village, with over international artists 20 local artists (music, theatre, 8 or bands 1dance, etc.) A festival rooted in the Pacific as much as in the francophone world The festival is of course linked to the famous Francofolies Festival in La Rochelle, France, but it is also strongly oriented towards the world of Oceania. The aim is to present the different cultures in the entire Pacific, including the English-speaking regions. The Francofolies New Caledonia will also present numerous groups interpreting the Kaneka, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of this style of music. -

Tinashe Flame Release

RELEASES NEW SINGLE “FLAME” “FLAME” IS AVAILABLE TODAY ON ALL PLATFORMS TINASHE SET FOR GUEST STARRING ROLE ON THE NEW SEASON OF EMPIRE, NAMED PEPSI’S SOUND DROP ARTIST EARNS ANOTHER BILLBOARD #1 WITH BRITNEY SPEARS COLLABORATION “SLUMBER PARTY” ON THE DANCE CHARTS March 16, 2017 – Los Angeles, CA – Platinum selling singer, songwriter, producer and entertainer Tinashe releases her brand new single today, “Flame.” The track, which was produced by Sir Nolan, is available at all digital retail and streaming partners. Listen to “Flame” iTunes/Apple Music: http://smarturl.it/iFlame Spotify: http://smarturl.it/spFlame Vevo: http://smarturl.it/pvFlame Amazon Music: http://smarturl.it/azFlame Google Play: http://smarturl.it/gpFlame The release of “Flame” follows on the heels of Tinashe’s critically acclaimed Nightride project, released late last year. The 14-track project, a companion piece to her upcoming studio album, includes stand-out track “Company.” The song recently received an attention-grabbing video clip, a full-on dance assault, all done in one take. To view the video for “Company,” click here. Nightride is the first of a two-part series, which will include Tinashe’s sophomore studio album, Joyride. With the projects representing two different sides of Tinashe, “Flame” is taken from the latter. Tinashe told Rolling Stone, “I see them as two things that are equally the same. I think you can be a combination of things, and that's what makes people human and complex. They are equally me. I don't like to be limited to one particular thing so I want to represent that duality and that sense of boundlessness in my art." As a go-to collaborator and hit maker, Tinashe has also recently appeared on tracks with the likes of Britney Spears, Davido, Tinie Tempah, Enrique Iglesias, KDA and Lost Kings. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

New Jersey LFN 2012-10 Packet for QUILL CORPORATION

New Jersey LFN 2012-10 Packet for QUILL CORPORATION CONTRACT #R141704 Solicited and awarded by REGION 4 EDUCATION SERVICE CENTER on behalf of itself and National IPA/TCPN participants New Jersey LFN 2012-10 Packet Table of Contents Required Document Contract Documents Screenshot Page from original solicitation that indicates Lead Agency and issuance of solicitation on behalf of themselves and National IPA and/or TCPN members nationally New Jersey Business Registration Certificate for the contractor and any subcontractors Statement of Corporate Ownership Public Contract EEO Compliance Non-Collusion Affidavit Solicitation Posting Documents Award and evaluation criteria from solicitation Bid opening and late submission policy from solicitation Notice of Intent to Award---Sample Disclosure of Investment Activities in Iran Checklist CONTRACT DOCUMENTS SCREENSHOT FROM WEBSITE PAGE FROM SOLICITATION THAT INDICATES LEAD AGENCY AND ISSUANCE OF SOLICITATION ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND NATIONAL IPA AND/OR TCPN MEMBERS 7145 West Tidwell Road ~ Houston, Texas 77092 (713) 744-6835 www.esc4.net Publication Date: August 28, 2014 NOTICE TO OFFEROR SUBMITTAL DEADLINE: Wednesday, October 8, 2014 @ 2:00 PM CDT Questions regarding this solicitation must be submitted in writing to Robert Zingelmann at [email protected] or (713) 744-6835 no later than October 1, 2014. All questions and answers will be posted to both www.esc4.net and www.tcpn.org under Solicitations. Offerors are responsible for viewing either website to review all questions and answers prior to submitting proposals. Please note that oral communications concerning this RFP shall not be binding and shall in no way excuse the responsive Offeror of the obligations set forth in this proposal. -

Artistes, Professionnels, Stars. L'histoire Du Rap En Français Au

Artistes, professionnels, stars. L’histoire du rap en français au prisme d’une analyse de réseaux Karim Hammou To cite this version: Karim Hammou. Artistes, professionnels, stars. L’histoire du rap en français au prisme d’une analyse de réseaux. Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel avec la collaboration de Luc Sigalo Santos. L’Art et la Mesure. Histoire de l’art et méthodes quantitatives, Editions Rue d’Ulm, 600 p., 2010. halshs-00471732 HAL Id: halshs-00471732 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00471732 Submitted on 8 Apr 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Artistes, professionnels, stars L’histoire du rap en français au prisme d’une analyse de réseaux Karim Hammou, chercheur associé au Centre Norbert Élias Les recherches que j’expose aujourd’hui s’inscrivent dans le cadre plus large d’une enquête socio- historique sur le développement d’une pratique professionnelle du rap en France. La sociologie du travail artistique a tendance à faire l’impasse sur la question de la valeur des artistes et de leurs œuvres. Deux positions principales dominent : l'analyse sociale de l’art rend compte d’un contexte professionnel, d’une division du travail, et abandonne la question du talent, de la valeur aux critiques et aux amateurs.