Restoring Housing Security and Stability In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Re Motion of Propublica, Inc. for the Release of Court Records [FISC

IN RE OPINIONS & ORDERS OF THIS COURT ADDRESSING BULK COLLECTION OF DATA Docket No. Misc. 13-02 UNDER THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT IN RE MOTION FOR THE RELEASE OF Docket No. Misc. 13-08 COURT RECORDS IN RE MOTION OF PROPUBLICA, INC. FOR Docket No. Misc. 13-09 THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 25 MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS, IN SUPPORT OF THE NOVEMBER 6,2013 MOTION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, ET AL, FOR THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS; THE OCTOBER 11, 2013 MOTION BY THE MEDIA FREEDOM AND INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THIS COURT'S SEPTEMBER 13, 2013 OPINION ON THE ISSUE OF ARTICLE III STANDING; AND THE NOVEMBER 12,2013 MOTION OF PRO PUBLICA, INC. FOR RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS Bruce D. Brown The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Amici Curiae November 26. 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE .................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................. -

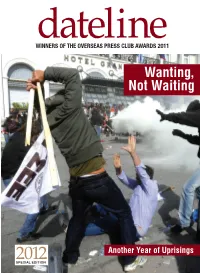

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

The Pentagon Papers Case and the Wikileaks Controversy: National Security and the First Amendment

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2011 The Pentagon Papers Case and the Wikileaks Controversy: National Security and the First Amendment Jerome A. Barron George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 1 Wake Forest J. L. & Pol'y 49 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V._JB_FINAL READ_NT'L SEC. & FA (DO NOT DELETE) 4/18/2011 11:10 AM THE PENTAGON PAPERS CASE AND THE WIKILEAKS CONTROVERSY: NATIONAL SECURITY AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT JEROME A. BARRON † INTRODUCTION n this Essay, I will focus on two clashes between national security I and the First Amendment—the first is the Pentagon Papers case, the second is the WikiLeaks controversy.1 I shall first discuss the Pentagon Papers case. The Pentagon Papers case began with Daniel Ellsberg,2 a former Vietnam War supporter who became disillusioned with the war. Ellsberg first worked for the Rand Corporation, which has strong associations with the Defense Department, and in 1964, he worked in the Pentagon under then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.3 He then served as a civilian government employee for the U.S. State Department in Vietnam4 before returning to the United † Harold H. Greene Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School (1998–present); Dean, The George Washington University Law School (1979– 1988); B.A., Tufts University; J.D., Yale Law School; LL.M., The George Washington University. -

Journalism 1

Journalism 1 deficiencies in foreign language who receive a Deferred Admission or JOURNALISM Admission by Review, may be considered for admission to the college. Students who are admitted through the Admission by Review process Description with core course deficiencies will have certain conditions attached to their enrollment at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. These conditions The journalism major is built on a solid base of instruction in reporting are explained under Admission to the University, Removal of Deficiencies. and writing, copy editing, visual communication and multimedia High school deficiencies must be removed during the first 30 credit hours journalism. The major also has broadened its curriculum in response to of enrollment at Nebraska (60 hours for foreign language) or the first advancing technology and new electronic and mobile media. Elective calendar year, whichever takes longer. choices include courses in magazine writing, depth reporting, feature writing, sports writing, business writing, photography, design, data Admission Deficiencies/Removal of Deficiencies visualization, Web design, videography and advanced editing. You must remove entrance deficiencies in geometry and foreign language before you can graduate from the College of Journalism and Mass Many of the journalism faculty members have extensive industry Communications. experience at a wide variety of media organizations such as The Miami Herald, ProPublica, The Detroit News, Business Week, Omaha Removing Foreign Language Deficiencies World-Herald, Seward County Independent, Lincoln Journal-Star and A student will need to complete the second semester of the first-year The New York Times. The faculty continues to be connected to the language sequence to clear the deficiency and the second semester of industry, and its members are actively involved in professional media the second-year language sequence to complete the college graduation organizations. -

Nothing Protects Black Women from Dying in Pregnancy and Childbirth Not Education

Journalism in the Public Interest MATERNAL HEALTH Nothing Protects Black Women From Dying in Pregnancy and Childbirth Not education. Not income. Not even being an expert on racial disparities in health care. by Nina Martin, ProPublica, and Renee Montagne, NPR Dec. 7, 8 a.m. EST This story was co-published with NPR. On a melancholy Saturday this past February, Shalon Irving’s “village” — the friends and family she had assembled to support her as a single mother — gathered at a funeral home in a prosperous black neighborhood in southwest Atlanta to say goodbye and send her home. The afternoon light was gray but bright, flooding through tall arched windows and pouring past white columns, illuminating the flag that covered her casket. Sprays of callas and roses dotted the room like giant corsages, flanking photos from happier times: Shalon in a slinky maternity dress, sprawled across her couch with her puppy; Shalon, sleepy-eyed and cradling the tiny head of her newborn daughter, Soleil. In one portrait Shalon wore a vibrant smile and the crisp uniform of the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service, where she had been a lieutenant commander. Many of the mourners were similarly attired. Shalon’s father, Samuel, surveyed the rows of somber faces from the lectern. “I’ve never been in a room with so many doctors,” he marveled. “… I’ve never seen so many Ph.D.s.” At 36, Shalon had been part of their elite ranks — an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the preeminent public health institution in the U.S. -

Propublica Report to Stakeholders May-August, 2014

ProPublica Report to Stakeholders The Power of Partnerships May-August, 2014 The latest in a series of periodic reports to our stakeholders about progress at ProPublica. Earlier reports, including our annual report for 2013 and report for the first period of 2014, are available at ProPublica.org. An Unequalled Breadth of Partnerships ProPublica has had 111 different publishing partners over six years—but per- haps more remarkable is the fact that we had 26 partners in the middle four months of 2014 alone. Both the quality and the range of these partnerships were noteworthy, including stories published exclusively with the New York Times, NPR News, the Washington Post, the Atlantic and WNYC. Our work also appeared in BuzzFeed, the Daily Beast, Mashable, Source, the Lens, Center for Investigative Reporting, Univision and Upworthy. We worked with Amazon on ebooks, and with other newspapers including the Albany Times Union, Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Dallas Morning News, Miami Herald, Newark Star-Led- ger, New York Daily News, Philadelphia Inquirer and Tampa Bay Times. Pro- Publica stories also ran in the magazines Marie Claire and Sports Illustrated. We pursue such partnerships carefully. Some are de- signed to get greater reach for important stories. But most are intended to maximize the chances that our work will have impact and spur change. So when we undertake a national story with a local angle, we’ll often publish the re- sult with a lead local outlet, where the story will naturally be of greater salience. A tale of abusive charges under Medicare that centered in Chicago, published in July in the Chicago Tribune, is a perfect example; so is the story published just two weeks later in the Tampa Bay Times about how a statute designed to protect against predatory auto title loans had been undermined in Florida. -

The New York Times 2014 Innovation Report

Innovation March 24, 2014 Executive Summary Innovation March 24, 2014 2 Executive Summary Introduction and Flipboard often get more traffic from Times journalism than we do. The New York Times is winning at journalism. Of all In contrast, over the last year The Times has the challenges facing a media company in the digi- watched readership fall significantly. Not only is the tal age, producing great journalism is the hardest. audience on our website shrinking but our audience Our daily report is deep, broad, smart and engaging on our smartphone apps has dipped, an extremely — and we’ve got a huge lead over the competition. worrying sign on a growing platform. At the same time, we are falling behind in a sec- Our core mission remains producing the world’s ond critical area: the art and science of getting our best journalism. But with the endless upheaval journalism to readers. We have always cared about in technology, reader habits and the entire busi- the reach and impact of our work, but we haven’t ness model, The Times needs to pursue smart new done enough to crack that code in the digital era. strategies for growing our audience. The urgency is This is where our competitors are pushing ahead only growing because digital media is getting more of us. The Washington Post and The Wall Street crowded, better funded and far more innovative. Journal have announced aggressive moves in re- The first section of this report explores in detail cent months to remake themselves for this age. First the need for the newsroom to take the lead in get- Look Media and Vox Media are creating newsrooms ting more readers to spend more time reading more custom-built for digital. -

Rebooting' Journalism, a Free Press – 2.6 Terabytes at a Time

A4 LIFESTYLESCLASSIFIEDCOMICSSPORTSJUMPEDIT A4 MONDAY, APRIL 11, 2016 OPINION THE NEWS-ITEM, SHAMOKIN, PA COMMENTARY Cheers and jeers The News-Item’s cheers and jeers for the past week of news: • Cheers to the effort by a a group of local resi- dents to honor police with their Spring Saunter/ Walk to Support Law Enforcement on Thursday night in Shamokin. There was a great turnout, including the presence of some young girls who recognize the value of local police. It’s always nice — no matter the cause — to see the commu- nity come together (and getting some exercise in a walk across town on a chilly spring evening — there’s another plus). It was sadly fitting that on the same front page in which we covered the walk was the story on the child porn-suicide attempt case in Shamokin — a reminder of Rebooting’ journalism, a free exactly the difficult circumstances that law enforcement face every day that were recognized by the walk. press – 2.6 terabytes at a time • Jeers to the Trevorton woman who wreaked havoc with her Ford 150 pickup when she BY GENE POLICINSKI INSIDE THE FIRST AMENDMENT crashed it into parked vehicles along Shamokin Street (Route 225) in the village Thursday, result- The rising global furor over the news operations. WikiLeaks’ 2010 sioned by this nation’s founders for a release of classified diplomatic cables robust and free press. From challeng- ing in damage to six other vehicles that simulat- trove of financial records and other came to just 1.7 gigabytes. Edward ing the nature of million-dollar con- ed a NASCAR pileup. -

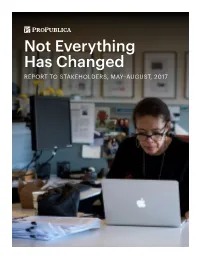

Not Everything Has Changed REPORT to STAKEHOLDERS, MAY–AUGUST, 2017 Not Everything Has Changed

Not Everything Has Changed REPORT TO STAKEHOLDERS, MAY–AUGUST, 2017 Not Everything Has Changed Much has changed since Election Day, November 8, including at ProPublica. We added new beats on immigration, the President’s personal business interests, white supremacy and hate crimes, extra reporting firepower on environmental issues, and much more—not to mention extensive coverage of the new administration, much of it focused on transparency. But the need for the deep-dive investigative report- Renee Montagne. It takes an unsparing look at why ing for which ProPublica is best known remains as the U.S. has the highest maternal death rate in the de- critical as it has ever been. In a short attention-span veloped world. Every year, 700 to 900 American wom- world, in an atmosphere of politics that sometimes en die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes seems divorced from policy, in a news ecosystem of- (with 60 percent of these deaths being preventable), ten addicted to quick clicks, shallow answers and an and some 65,000 women come very close to dying. absence of context, ProPublica proudly marches to a And while maternal mortality has declined signifi- different drummer. cantly in other wealthy countries in recent years, it is Over the middle period of 2017, ProPublica took on rising in the U.S. stories that other news organizations would pass on as After launching the series with the harrowing being too complex, time-consuming or legally risky. story of Lauren Bloomstein, a neonatal nurse who This kind of journalism is an essential and effective died in childbirth in the hospital where she worked weapon against abuses of power and betrayals of the — of preeclampsia, a preventable type of high blood public trust. -

ANNUAL REPORT Highlights of the Year at Propublica

At the Frontiers of the New Data Journalism 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Highlights of the Year at ProPublica ▪▪Impact: Real change produced as a result of our ▪▪Award-winning: Generous recognition from journalism, from an abusive lender driven out of our peers, including ProPublica’s first two Emmy business to heightened vigilance for drug use in Awards—for outstanding long-form investigative nursing homes, from more aggressive enforcement journalism and research, Online Journalism and against housing discrimination to important limits Investigative Reporters and Editors Awards for in- on the use of physical restraints on school children. novation, the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for new media, the Gerald Loeb Award for business ▪▪Great stories: Memorable journalism on critical commentary, the Hechinger Grand Prize for Distin- areas ranging from patient safety and patient pri- guished Education Reporting, a Society for News vacy to efforts to undermine the nation’s workers’ Design Gold Medal and the PEN Center USA Award comp system, from management shortcomings of Honor. at the American Red Cross to inequities in debt collection, from revealing shortcomings in rape ▪▪Analytic rigor: Important advances in the so- investigations to exploding myths about the war on phistication of statistical analyses accompanying drugs—and much, much more. many of our major stories, and the development and refinement of “white papers” making this work ▪▪Growing platform: Considerable growth in our transparent and comprehensible. audience and publishing platform, with monthly average page views at 2.3 million, up 39% over 2014 ▪▪Business success: Further steps toward sus- and monthly average unique visitors at 960,000, tainability, with our sixth straight year of operating up 43%, while our Twitter following ended the year surplus, the reduction of the proportion of funding over 412,000 up 23% and our cadre of Facebook from our founding donors to less than 24% even fans stands above 124,000, up 32%. -

Pooled Journalism Funds Could Help Save Local Newspapers by Julie Sandorf MARCH 3, 2021

OPINION Pooled Journalism Funds Could Help Save Local Newspapers By Julie Sandorf MARCH 3, 2021 Thank you for reading the Chronicle of Philanthropy. You have 1 free article remaining. Subscribe for unlimited access. Save more than 20% off our lowest rate. Claim This Offer JOHN J. KIM, CHICAGO TRIBUNE, TNS, ZUMA WIRE The civic health of communities across the country was dealt yet another blow last month when the hedge fund Alden Global Capital announced it would acquire Tribune Publishing. If past is prologue, Alden’s takeover means major jobs cuts and shuttered newsrooms at such storied institutions as the Chicago Tribune, the Hartford Courant, the New York Daily News, the Orlando Sentinel, and many others in cities large and small. This troubling development did come with one bright spot. A nonprofit supported by Maryland business executive and philanthropist Stewart Bainum Jr. acquired the Baltimore Sun and several other newspapers in the state from Tribune Publishing rather than see them decimated by Alden. Bainum’s Sunlight for All Institute intends to operate the newspapers “for the benefit of the community,” the Sun reported. The divergent paths taken by Alden and Bainum illustrate the two increasingly common ways local journalism is financed: by investors with little connection to the communities in which their publications operate and by philanthropists and civic leaders who see the publications as essential community assets. The first option is unsustainable, and the second is often unrealistic since wealthy philanthropists like Bainum can’t save every struggling local newspaper in the country. Fortunately, there is a third option and one that philanthropy should enthusiastically embrace — pooled funds or giving circles to support local media. -

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCES the 104Th ANNUAL PULITZER PRIZES in JOURNALISM, LETTERS, DRAMA and MUSIC

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCES THE 104th ANNUAL PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM, LETTERS, DRAMA AND MUSIC New York, NY (May 4, 2020) – The 104th annual Pulitzer Prizes in Journalism, Letters, Drama and Music were announced today. The winners in each category, along with the names of the finalists in the competition, follow: A. PRIZES IN JOURNALISM 1. PUBLIC SERVICE For a distinguished example of meritorious public service by a newspaper or news site through the use of its journalistic resources, including the use of stories, editorials, cartoons, photographs, graphics, videos, databases, multimedia or interactive presentations or other visual material, a gold medal. Awarded to The Anchorage Daily News, in collaboration with ProPublica, for a riveting series that revealed a third of Alaska’s villages had no police protection, took authorities to task for decades of neglect, and spurred an influx of money and legislative changes. Also nominated as finalists in this category were: The New York Times for exemplary reporting that exposed the breadth and impact of a political war on science, including systematic dismantling of federal regulations and policy, and revealed the implications for the health and safety of all Americans; and The Washington Post for groundbreaking, data-driven journalism that used previously hidden government records and confidential company documents to provide unprecedented insight into America’s deadly opioid epidemic. 2. BREAKING NEWS REPORTING For a distinguished example of local reporting of breaking news that, as quickly as possible, captures events accurately as they occur, and, as time passes, illuminates, provides context and expands upon the initial coverage, Fifteen thousand dollars ($15,000).