The Pentagon Papers Case and the Wikileaks Controversy: National Security and the First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Tape Subject

1 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) Conversation No. 140-1 Date: August 14, 1972 Time: 7:55 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The Camp David operator talked with the President. Request for a call to John D. Ehrlichman -Ehrlichman’s location Conversation No. 140-2 Date: August 15, 1972 Time: Unknown between 8:43 pm and 9:30 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with the Camp David operator. [See Conversation No. 202-12] Request for a call to Julie Nixon Eisenhower Conversation No. 140-3 Date: August 15, 1972 Time: 9:30 pm - 9:35 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with Julie Nixon Eisenhower. [See Conversation No. 202-13] 2 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) ***************************************************************** BEGIN WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [Personal returnable] [Duration: 4m 57s ] END WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 ***************************************************************** Conversation No. 140-4 Date: August 16, 1972 Time: Unknown between 8:15 am and 8:21 am Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with the Camp David operator. [See Conversation No. 202-14] Request for a call to Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Conversation No. 140-5 Date: August 16, 1972 Time: 8:21 am - 8:29 am Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with Alexander M. Haig, Jr. [See Conversation No. 202-15] Paul C. Warnke -George S. McGovern's statement -Possible briefing of Warnke -Security clearance process -Questions on Pentagon Papers 3 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) -The President’s instructions -Report by Richard M. -

NAPF Report to UN Secretary General on Disarmament Education

Report to UN Secretary-General on NAPF Disarmament Education Activities The Nuclear Age Peace Foundation (NAPF) has been educating people in the United States and around the world about the urgent need for the abolition of nuclear weapons since 1982. Based in Santa Barbara, California, the Foundation’s mission is to educate and advocate for peace and a world free of nuclear weapons, and to empower peace leaders. The following document was submitted to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. It will make up a portion of the “Report of the Secretary-General to the 69th Session of the General Assembly on the Implementation of the Recommendations of the 2002 UN Study on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Education.” Websites www.wagingpeace.org NAPF’s primary website, www.wagingpeace.org, serves as an educational and advocacy tool for members of the public concerned about nuclear weapons issues. During this reporting period, there were over 700,000 unique visitors to this site. The Waging Peace site covers current nuclear weapons policy and other relevant issues of global security. It includes information about the Foundation’s activities and offers visitors the opportunity to participate in online advocacy and activism. The site additionally offers a unique archive section containing hundreds of articles and essays on issues ranging from nuclear weapons policy to international law and youth activism. The site is updated frequently. www.nuclearfiles.org The Foundation’s educational website, www.nuclearfiles.org, details a comprehensive history of the Nuclear Age. It is regularly updated and expanded. By providing background information, an extensive timeline, access to primary documents and analysis, this site is one of the preeminent online educational resources in the field. -

In Re Motion of Propublica, Inc. for the Release of Court Records [FISC

IN RE OPINIONS & ORDERS OF THIS COURT ADDRESSING BULK COLLECTION OF DATA Docket No. Misc. 13-02 UNDER THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT IN RE MOTION FOR THE RELEASE OF Docket No. Misc. 13-08 COURT RECORDS IN RE MOTION OF PROPUBLICA, INC. FOR Docket No. Misc. 13-09 THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 25 MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS, IN SUPPORT OF THE NOVEMBER 6,2013 MOTION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, ET AL, FOR THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS; THE OCTOBER 11, 2013 MOTION BY THE MEDIA FREEDOM AND INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THIS COURT'S SEPTEMBER 13, 2013 OPINION ON THE ISSUE OF ARTICLE III STANDING; AND THE NOVEMBER 12,2013 MOTION OF PRO PUBLICA, INC. FOR RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS Bruce D. Brown The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Amici Curiae November 26. 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE .................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................. -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

The American War in Indochina: Injustice and Outrage Revista De Paz Y Conflictos, Núm

Revista de Paz y Conflictos E-ISSN: 1988-7221 [email protected] Universidad de Granada España Gray, Truda; Martin, Brian The American War in Indochina: Injustice and Outrage Revista de Paz y Conflictos, núm. 1, 2008, pp. 6-28 Universidad de Granada Granada, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=205016386002 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto issn: 1988-7221 Th e American War in Indochina: Injustice and Outrage. número 1 año 2008 número La guerra del Vietnam: Injusticia y Ultraje Truda Gray and Brian Martin School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, Australia. Resumen Muchas de las acciones del ejército de los Estados Unidos durante la guerra de Indo- china, en las que se utilizó la capacidad de disparo en una escala sin precedentes, eran potenciales generadores de indignación en Indochina, en los Estados Unidos y en otros lugares. El examen de tres aspectos interconectados de las operaciones militares de los Estados Unidos en la guerra de Indochina (los bombardeos, el Programa Phoenix y la masacre de My Lai) proporciona numerosos ejemplos de cómo trató el gobierno esta- dounidense de impedir que sus acciones generaran indignación. Los métodos usados se pueden clasifi car en cinco categorías: ocultamiento de la acción; minusvaloración del objetivo; reinterpretación de la acción; uso de canales ofi ciales para hacer parecer justa la acción; fi nalmente, intimidación y soborno de personas implicadas. -

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Adam Yarmolinsky Interviewer: Daniel Ellsberg Date of Interview: November 28, 1964 Place of Interview: Length: 29 Pp

Adam Yarmolinsky Oral History Interview –JFK #2, 11/28/1964 Administrative Information Creator: Adam Yarmolinsky Interviewer: Daniel Ellsberg Date of Interview: November 28, 1964 Place of Interview: Length: 29 pp. Biographical Note Yarmolinsky, Adam; Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense (1961-1965). Yarmolinsky discusses his role in converting the Civil Defense program into the Department of Defense. He discusses the Kennedy Administration’s concern for nuclear war, Robert S. McNamara’s involvement, and McNamara’s position regarding nuclear war, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed July 14, 1967, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

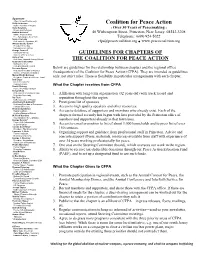

Read the Guidelines for Chapters

Sponsors Titles for identification only Philip Anderson Coalition for Peace Action Nobel Laureate in Physics Harry Belafonte Over 30 Years of Peacemaking Singer and Performer Balfour Brickner* 40 Witherspoon Street, Princeton, New Jersey, 08542-3208 Rabbi, Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, New York Telephone: (609) 924-5022 Noam Chomsky Professor of Linguistics, MIT [email protected] www.peacecoalition.org William Sloane Coffin* President Emeritus National Peace Action George Councell Episcopal Bishop GUIDELINES FOR CHAPTERS OF Diocese of New Jersey Harvey Cox Professor, Harvard Divinity School THE COALITION FOR PEACE ACTION Sudarshana Devadhar Bishop, NJ Area United Methodist Church Freeman Dyson Below are guidelines for the relationship between chapters and the regional office Professor Emeritus of Physics Institute of Advanced Studies (headquarters) of the Coalition for Peace Action (CFPA). They are intended as guidelines Marian Wright Edelman President, Children’s Defense Fund only, not strict rules. There is flexibility in particular arrangements with each chapter. Bob Edgar Executive Director Common Cause Daniel Ellsberg What the Chapter receives from CFPA Former Pentagon Analyst Richard Falk Professor of International Law 1. Affiliation with long-term organization (32 years old) with track record and Princeton University Val Fitch reputation throughout the region. Nobel Laureate in Physics John Kenneth Galbraith* 2. Prestigious list of sponsors Professor Emeritus of Economics Harvard University 3. Access to high quality speakers and other resources. Thomas Gumbleton Roman Catholic 4. Access to database of supporters and members who already exist. Each of the Auxiliary Bishop of Detroit W. Reed Gusciora chapters formed recently has begun with lists provided by the Princeton office of Assemblyman, NJ Legislature George Kennan* members and supporters already in that town/area. -

Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 1 Article 3 2016 Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit Floyd Abrams Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Floyd Abrams, Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 11 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE SPEECH AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN THE SECOND CIRCUIT Floyd Abrams* INTRODUCTION Much of the development of First Amendment law in the United States has occurred as a result of American courts rejecting well-established principles of English law. The U.S. Supreme Court has frequently rejected English law, permitting far more public criticism of the judiciary than would be countenanced in England, rejecting English libel law as being insufficiently protective of freedom of expression1 and holding that even hateful speech directed at minorities receives the highest level of constitutional protection.2 The Second Circuit has played a major role in the movement away from the strictures of the law as it existed in the mother country. In some areas, dealing with the clash between claims of national security and freedom of expression, the Second Circuit predated the Supreme Court’s protective First Amendment rulings. -

The New York Times Paywall

9-512-077 R E V : JANUARY 31, 2013 VINEET KUMAR BHARAT ANAND SUNIL GUPTA FELIX OBERHOLZER - GEE The New York Times Paywall Every newspaper in the country is paying close, close attention [to the Times paywall], wondering if they can get readers of online news to pay. Is that the future, or a desperate attempt to recreate the past?. Will paywalls work for newspapers? — Tom Ashbrook, host of On Point, National Public Radio1 On March 28, 2011, The New York Times (The Times) website became a restricted site. The home page and section front pages were unrestricted, but users who exceeded the allotted “free quota” of 20 articles for a month were directed to a web page where they could purchase a digital subscription. The paywall was launched earlier on March 17, 2011, in Canada, which served as the testing ground to detect and resolve possible problems before the global launch. The Times website had been mostly free for its entire existence, except for a few months in 2006–2007 when TimesSelect was launched. Traditional newspapers had been struggling to maintain profitability in the online medium, and they were eager to see how the public would react to the creation of a paywall at the most popular news website in the U.S. Martin Nisenholtz, the senior vice president of Digital Operations at The Times, was optimistic about the willingness of users to pay: I think the majority of people are honest and care about great journalism and The New York Times. When you look at the research that we’ve done, tons of people actually say, “Jeez, we’ve felt sort of guilty getting this for free all these years. -

Wikileaks, the First Amendment and the Press by Jonathan Peters1

WikiLeaks, the First Amendment and the Press By Jonathan Peters1 Using a high-security online drop box and a well-insulated website, WikiLeaks has published 75,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Afghanistan,2 nearly 400,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Iraq,3 and more than 2,000 U.S. diplomatic cables.4 In doing so, it has collaborated with some of the most powerful newspapers in the world,5 and it has rankled some of the most powerful people in the world.6 President Barack Obama said in July 2010, right after the release of the Afghanistan documents, that he was “concerned about the disclosure of sensitive information from the battlefield.”7 His concern spread quickly through the echelons of power, as WikiLeaks continued in the fall to release caches of classified U.S. documents. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton condemned the slow drip of diplomatic cables, saying it was “not just an attack on America's foreign policy interests, it [was] an attack on the 1 Jonathan Peters is a lawyer and the Frank Martin Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he is working on his Ph.D. and specializing in the First Amendment. He has written on legal issues for a variety of newspapers and magazines, and now he writes regularly for PBS MediaShift about new media and the law. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Noam N. Levey and Jennifer Martinez, A whistle-blower with global resonance; WikiLeaks publishes documents from around the world in its quest for transparency, L.A. -

Conflicted: the New York Times and the Bias Question Epilogue CSJ-10

CSJ‐ 10‐ 0034.2 PO Conflicted: The New York Times and the Bias Question Epilogue New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller’s rebuttal ran adjacent to Ombudsman Clark Hoyt’s column on the Times’ website on February 6, 2010. Neither Hoyt’s column nor Keller’s response ran in the paper. Keller opened by offering a quick and forceful endorsement of the Times’ Jerusalem bureau chief, Ethan Bronner. Then Keller argued that the decision to keep Bronner in Jerusalem was made out of respect for open‐minded readers who, he said, Hoyt improperly implied were not capable of distinguishing reality from appearances. He noted that the paper’s rulebook properly gave editors wide latitude to act in conflict of interest cases. Indeed, he continued, a journalist’s personal connections to a subject could contribute depth and texture to their reporting. As examples, he cited C.J. Chivers, Anthony Shadid, and Nazila Fathi. However, he chose not to go into detail about their biographies. Nor did he write about columnist Thomas Friedman and the instances in which he was touched by the Israeli‐Palestinian conflict. Instead, Keller observed that, as a reader, he could discern nothing in these journalists’ reporting that betrayed their personal feeling about the issues they covered. Finally, he closed with the argument that the paper had to be careful not to capitulate to partisans on either side of a conflict. To submit to their demands would rob the paper of experienced journalists like Bronner, whereas in fact the partisans were incapable of fairly evaluating him. This did not mean, he said, that he was denying the significance of Bronner’s family connections to Israel.