Living Obituary – Derek K Hitchins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Putting Systems to Work

i PUTTING SYSTEMS TO WORK Derek K. Hitchins Professor ii iii To my beloved wife, without whom ... very little. iv v Contents About the Book ........................................................................xi Part A—Foundation and Theory Chapter 1—Understanding Systems.......................................... 3 An Introduction to Systems.................................................... 3 Gestalt and Gestalten............................................................. 6 Hard and Soft, Open and Closed ............................................. 6 Emergence and Hierarchy ..................................................... 10 Cybernetics ........................................................................... 11 Machine Age versus Systems Age .......................................... 13 Present Limitations in Systems Engineering Methods............ 14 Enquiring Systems................................................................ 18 Chaos.................................................................................... 23 Chaos and Self-organized Criticality...................................... 24 Conclusion............................................................................ 26 Chapter 2—The Human Element in Systems ......................... 27 Human ‘Design’..................................................................... 27 Human Predictability ........................................................... 29 Personality ............................................................................ 31 Social -

Une Approche Paradigmatique De La Conception Architecturale Des Systèmes Artificiels Complexes

Une approche paradigmatique de la conception architecturale des systèmes artificiels complexes Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Paris-Saclay préparée à l’École Polytechnique NNT : 2018SACLX083 École doctorale n◦580 Sciences et technologies de l’information et de la communication (STIC) Spécialité de doctorat : Informatique Thèse présentée à Palaiseau, le 19 novembre 2018, par Mr. Jean-Luc Wippler Composition du Jury : Mr. Vincent Chapurlat Professeur, IMT Mines Alès Président Mme. Claude Baron Professeur des universités, INSA Toulouse Rapporteur Mr. Eric Bonjour Professeur des universités, Université de Lorraine, ENSGSI Rapporteur Mme. Marija Jankovic Professeur associé, CentraleSupélec Examinateur Mr. Olivier de Weck Professeur, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Examinateur Mr. Eric Goubault Professeur, École Polytechnique Examinateur Mr. Dominique Luzeaux IGR, École Polytechnique Directeur de thèse Une approche paradigmatique de la conception architecturale des systèmes artificiels complexes Jean-Luc Wippler c Copyright Jean-Luc Wippler – 2018 Certaines images utilisées dans ce manuscrit sont protégées par une licence c (Creative Commons). Plus particulièrement : b Gan Khoon Lay. b Lluisa Iborra. b Alice Noir et Yasser Magahed. ii À Élisa, mon amour de toujours. À Alfredo, il mio nonno, et à Luciano, mon parrain. «Perché l’architettura è tra tutte le arti quella che più arditamente cerca di riprodurre nel suo ritmo l’ordine dell’universo, che gli antichi chiamavano kosmos, e cioè ornato; in quanto è come un grande animale su cui rifulge la perfezione e la proporzione di tutte le sue membra. E sia lodate il Creatore Nostro che, come dice Agostino, ha stabilito tutte le cose in numero, peso e misura.» « Car l’architecture est, d’entre tous les arts, celui qui cherche avec le plus de hardiesse à reproduire dans son rythme l’ordre de l’univers, que les anciens appelaient kosmos, à savoir orné, dans la mesure où elle est comme un grand animal sur lequel resplendit la perfection et la proportion de tous ses membres. -

Report 2018-19

REPORT 2018-19 The annual report of Trinity College, Oxford CONTENTS The Trinity Community Obituaries President’s Report 2 Peter Brown 63 The Fellowship and Lecturers 4 Sir Fergus Millar 65 Fellows’ News 8 Justin Cartwright 67 REPORT 2018-19 Members of Staff 15 Bill Sloper 69 New Undergraduates 17 Old Members 70 New Postgraduates 18 Degrees, Schools Results and Awards 19 Reviews The annual report of Trinity College, Oxford The College Year Book Review 91 On the cover Some of the JCR Access Senior Tutor’s Report 25 Ambassadors and helpers Outreach & Access Report 26 Notes and Information at an Open Day for Estate Bursar’s Report 28 potential applicants Information for Old Members 92 Domestic Bursar’s Report 30 Inside front cover Editor’s note 92 Director of Development’s Report 31 Old Members attending Benefactors 33 the Women at Trinity day in September, which marked Library Report 41 the 40th anniversary of the Archive Report 47 admission of women Garden Report 51 Junior Members JCR Report 54 MCR Report 55 Clubs and Societies 56 Blues 62 1 THE TRINITY COMMUNITY President’s Report Marta Kwiatkowska, Professorial Fellow in Computing Systems, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in recognition of her outstanding s I write this report, work on contribution to the field of computer the new building means that science, with further recognition Athe college estate is being through the award of the prestigious transformed around us with a fairly constant low-level rumble of earth- moving equipment. Following planning ‘Trinity’s Fellowship has permission gained in October 2018, again distinguished itself we moved swiftly to detailed designs, with a raft of awards.’ demolition and preparation of the site, through to the start of the construction Lovelace Medal. -

AA08 A4 16Pg Hbook

INCOSE UK SEASON Report 2009 (Systems Engineering Annual State of the Nation) Prepared by the SEASON Working Group Published by the UK Chapter of the International Council on Systems Engineering © INCOSE UK Ltd, February 2009 Distribution This report will be available to INCOSE UK and UKAB membership from 1 February 2009 as an exclusive member benefit. It will be available on the INCOSE UK public web site on or after 1 July 2009. Disclaimer and Copyright Reasonable endeavours have been used throughout its preparation to ensure that the SEASON REPORT is as complete and correct as is practical. INCOSE, its officers and members shall not be held liable for the consequences of decisions based on any information contained in or excluded from this report. Inclusion or exclusion of references to any organisation, individual or service shall not be construed as endorsement or the converse. Where value judgements are expressed these are the consensus view of expert and experienced members of INCOSE UK and UKAB. The copyright of this work is vested in INCOSE UK Ltd. Where other sources are referenced the copyright remains with the original author. Any material in this work may be referenced or quoted with appropriate attribution. © INCOSE UK Ltd 2009 issue 01 february 2009 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Background to the SEASON report 4 What is INCOSE? 4 Invitation to participate 4 Disclaimer and Copyright 4 POSTSCRIPT June 2009 4 Systems Engineering in the UK 5 What is a system? 5 What is Systems Engineering? 5 Application of Systems -

Reengineering Systems Engineering Joseph Kasser, National University of Singapore; Derek Hitchins, ASTEM, Consultant Systems Architect; Thomas V

rd 3 Asia-Pacific Conference on Welcome from the Systems Engineering General Chair APCOSE 2009 Singapore Welcome to the 19th Annual INCOSE International Symposium (INCOSE 2009), which will be held in conjunction with the 3rd July 20 - 23 Asia-Pacific Conference on Systems Engineering (APCOSE 2009) from 20-23 July 2009. As the General Chair, I have the pleasure to welcome you to the choice international forum of the systems engineering community. The theme of the symposium, East meets West: The Human Dimension to Systems Engineering, highlights the human cognitive dimension as an integral part of systems thinking and systems engineering processes across different cultures. Moreover, human capital and capability form the fundamental basis for large-scale systems engineering. This is the first time that the INCOSE Symposium is held in Singapore and in Asia. Jointly hosted by INCOSE Region VI Chapters of Australia, Beijing, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan, the symposium reflects the growth of systems engineering as an emerging discipline in the region. This premier event will present researchers, students, educators, academics, professionals, public and private organisations from the East and East Meets West the West the opportunity to share and deliberate on the latest The Human Dimension to Systems Engineering systems engineering developments in education, research and applications. I believe this mutual exchange of ideas across different cultures can only spur greater dynamism and thinking in stretching the existing boundaries of systems engineering. Hosted by the Region VI Chapters of Finally, Singapore with its strategic location and world-class Australia, Beijing, Japan, Korea, infrastructure, serves as the logical meeting place for industry, Singapore and Taiwan academia and government from East and West to network, develop and grow partnerships. -

System Evaluation and Description Using Abstract Relation Types (ART)

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine Engineering Management and Systems Engineering Management and Systems Engineering Faculty Research & Creative Works Engineering 01 Apr 2007 System Evaluation and Description Using Abstract Relation Types (ART) Joseph J. Simpson Ann K. Miller Missouri University of Science and Technology Cihan H. Dagli Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/engman_syseng_facwork Part of the Operations Research, Systems Engineering and Industrial Engineering Commons Recommended Citation J. J. Simpson et al., "System Evaluation and Description Using Abstract Relation Types (ART)," Proceedings of the 1st Annual IEEE Systems Conference 2007, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Apr 2007. The definitive version is available at https://doi.org/10.1109/SYSTEMS.2007.374670 This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Engineering Management and Systems Engineering Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2007 1st Annual IEEE Systems Conference Waikiki Beach, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA April 9-12, 2007 SYSTEM EVALUATION AND DESCRIPTION USING ABSTRACT RELATION TYPES (ART) Joseph J. Simpson Dr. Cihan H. Dagli Dr. Ann Miller System Concepts UMR-Rolla UMR- Rolla 6400 32nd Ave. NW #9 229 EMSE Dept. Dept. of E&CE Seattle, WA 98107 Rolla, MO 65409-0370 Rolla, MO 65409-0040 206-781-7089 573-341-4374 573-341-6339 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract - Two abstract relation types (ART) represented as matrices, directed graphs or are developed to represent, describe and lattices [2]. -

4.3.2 Integrating Systems Science, Systems

Integrating Systems Science, Systems Thinking, and Systems Engineering: understanding the differences and exploiting the synergies (Mr) Hillary Sillitto Thales UK Copyright (c) Thales 2012, Permission granted to INCOSE to publish and use Abstract: There is a need to properly define the “intellectual foundations of systems engineering”; and we need to look beyond systems engineering to do this. This paper presents a new framework for understanding and integrating the distinct and complementary contributions of systems science, systems thinking, and systems engineering to create an “integrated systems approach”. The key step is to properly separate out and understand the relationship between the triad of: systems science as an objective “science of systems”; systems thinking as concerned with “understanding systems in a human context”; and systems engineering as “creating, adjusting and configuring systems for a purpose”. None of these is a subset of another; all have to be considered as distinct though interdependent subjects. A key conclusion of the paper is that the “correct” choice of system boundary for a particular purpose depends on the property of interest. The insights necessary to inform this choice belong in the domain of “systems thinking”, which thus provides a key input to “systems engineering”. In many systems businesses, the role of “systems architect” or “systems engineer” integrates the skills of systems science, systems thinking and systems engineering - which are therefore all essential competencies for the role. Background An integrated systems approach for solving complex problems needs to combine elements of systems science, systems thinking and systems engineering. But as these different communities come together, they find that assumptions underpinning their worldviews are not shared. -

Characterization and Application of User-Centred System Tools As Systems Engineering Support for Satellite Projects

UNIVERSITÄT DER BUNDESWEHR MÜNCHEN FAKULTÄT FÜR LUFT- UND RAUMFAHRTTECHNIK INSTITUT FÜR RAUMFAHRTTECHNIK UND WELTRAUMNUTZUNG Characterization and Application of User-Centred System Tools as Systems Engineering Support for Satellite Projects Tanja Nemetzade Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Luft- und Raufahrttechnik der Universität der Bundeswehr München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN (DR.-ING.) genehmigten Dissertation. Gutachter/Gutachterin: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Roger Förstner 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Kristin Paetzold Diese Dissertation wurde am 23.05.2019 bei der Universität der Bundeswehr München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Luft- und Raumfahrttechnik am 12.12.2019 angenommen. Die mündliche Prüfung fand am 16.01.2020 statt. Das Ganze ist mehr als die Summe seiner Teile. Aristoteles Danksagung Diese Arbeit wäre nicht möglich gewesen, wenn ich die letzten Jahre nicht durch viele Menschen unterstützt worden wäre. Meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr.-Ing. Roger Förstner vom Institut für Raumfahrttechnik und Weltraum- nutzung der Universität der Bundeswehr München danke ich herzlich für die umfassende akademische Betreuung dieser Arbeit. Jede der vielen kurzweiligen Besprechungen führte zu wertvollen Denkanstößen und vermittelte das gute Gefühl, als Systemmensch verstanden zu werden. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Kristin Paetzold vom Institut für Technische Produktentwicklung der Universität der Bun- deswehr München danke ich für die Inspirationen aus einer Nicht-Raumfahrtbranche. Ehemaligen und aktuellen Mitarbeitern der Firma Airbus Defence and Space GmbH, die mir diese Arbeit erst ermöglicht haben, gilt mein besonderer Dank. Insbesondere möchte ich Herrn Andreas Lindenthal und Herrn Dr. Marc Steckling danken, die stets an mich und den Erfolg dieser Arbeit geglaubt haben. Herrn Dr. -

A Systems Engineering Approach to Design of Complex Systems

A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems Sagar Behere 03 July 2014 Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Stockholm A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 1 / 99 N Contents 1 Systems Engineering 2 Requirements 3 Architecture 4 Testing, Verication and Validation 5 Safety 6 Model based systems engineering A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 2 / 99 N Who are we? KTH: Machine Design/Mechatronics & Embedded Control Systems A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 3 / 99 N Who am I? 10+ years of systems development Diesel engines, autonomous driving, robotics, aviation A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 4 / 99 N Question How will you go about developing a quadrocopter? A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 5 / 99 N Systems Engineering What is Systems Engineering? A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 6 / 99 N Systems Engineering A plethora of denitions ;-) "...an interdisciplinary eld of engineering that focuses on how to design and manage complex engineering projects over their life cycles." [source: Wikipedia] "...a robust approach to the design, creation, and operation of systems." [source: NASA Systems Engineering Handbook, 1995] "The Art and Science of creating eective systems..." [source: Derek Hitchins, former President of INCOSE] A systems engineering approach to design of complex systems 7 / 99 N Systems Engineering The systems engineering process [source: A. T. Bahill and B. Gissing, Re-evaluating -

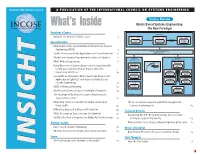

Systems Engineering

December 2009 | Volume 12 Issue 4 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON SYSTEMS ENGINEERING What’s Inside Model-Based Systems Engineering: The New Paradigm President’s Corner SysML Tools Inclusive Thinking for INCOSE’s Future 3 RSA/E+/SysML No Magic/SysML RSA/E+/SysML Operational Factory Excavator Excavator Model System Model Scenario Executable Special Feature Scenario Introduction to this Special Edition on Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE) 7 Interface & Transformation Tools SysML: Lessons from Early Applications and Future Directions 10 (VIATRA, XaiTools,…) Model-based Systems Engineering for Systems of Systems 12 Traditional Traditional Descriptive Tools Simulation & Analysis Tools MBSE Methodology Survey 16 Model Center NX/MCAD Tool Optimization Using Model-based Systems Engineering to Supplement the Excavator Model Certification-and-Accreditation Process of the U.S. Boom Model Ansys Mathematica Department of Defense 19 Reliability Factory CAD FEA Model Model Factory Executable and Integrative Whole-System Modeling via the Layout Model Application of OpEMCSS and Holons for Model-based Excel Dymola Dig Cycle Cost Model Systems Engineering 21 Excel Model Production MBSE in Telescope Modeling 24 Ramps eM-Plant Factory Model-based Systems Praxis for Intelligent Enterprises 34 Simulation 2009-02-25a The Challenge of Model-based Systems Engineering for Space Systems, Year 2 36 Integrating System Design with Simulation and Analysis The Use of Systems Engineering Methods to Explain the Using SysML 40 Success of an Enterprise -

Enterprise Architecture in the Rail Domain

EA, IA, O Enterprise Architecture in the Rail Domain [email protected] [1] Wikipedia "Old MacDonald Had a Farm" is a children's song about a farmer named MacDonald (or McDonald) and the various animals he keeps on his farm. Each verse of the song changes the name of the animal and its respective noise. In many versions, the song is cumulative, with the noises from all the earlier verses added to each subsequent verse. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 745. Renowned computer scientist Donald Knuth jokingly shows the song to have a complexity of in "The Complexity of Songs," attributing its source to "a Scottish farmer O. McDonald." [2] [3] Systems Engineering (SE) Systems of Systems (SoS) Enterprise Architecture (EA) Information Architecture (IA) Ontology (O) [4] Systems Engineering The Art and Science of creating effective systems, using whole system, whole life principles" OR "The Art and Science of creating optimal solution systems to complex issues and problems"[8] — Derek Hitchins, Prof. of Systems Engineering, former president of INCOSE (UK), 2007. [5] A logical sequence of activities and decisions that transforms an operational need into a description of system performance parameters and a preferred system configuration. (MIL-STD-499A, Engineering Management, 1 May 1974. Now cancelled.) An interdisciplinary approach that encompasses the entire technical effort, and evolves into and verifies an integrated and life cycle balanced set of system people, products, and process solutions that satisfy customer needs. (EIA Standard IS-632, Systems Engineering, December 1994.) An interdisciplinary, collaborative approach that derives, evolves, and verifies a life-cycle balanced system solution which satisfies customer expectations and meets public acceptability. -

Clarifying the Relationships Between Systems Engineering, Project

Asia-Pacific Council on Systems Engineering Conference (APCOSEC), Yokohama, 2013 Clarifying the Relationships between Systems Engineering, Project Management, Engineering and Problem Solving Joseph Kasser Derek Hitchins Temasek Defence Systems Institute ASTEM National University of Singapore, Consultant Systems Architect Block E1, #05-05 1 Engineering Drive 2, Singapore 117576 [email protected] Abstract. This paper resolves the problem of the overlap between systems engineering and project management. The paper uses the “systems engineering – the activity” (SETA) paradigm to view the activities performed in realizing a system. The paper: 1. Shows that problem solving and systems engineering are identical in concept but vary in de- tail depending on whether the problem is complex or non-complex. 2. Provides a concept map showing a non-overlapping relationship between the activities known as project management, systems engineering, Engineering and holistic thinking in the SETA paradigm. 3. Links risk management activities and domain knowledge into the relationships. Key words systems engineering, project management, engineering, problem solving. 1. Introduction The relationship between systems engineering, project management, engineering and problem solving in the literature is confusing, containing overlaps and contradictions. This paper attempts to clarify the situation based on research that distinguished between the following two systems engineering para- digms (Kasser, 2013a) Chapter 29): systems engineering – the role (SETR), a job being what systems engineers do in the work- place, and systems engineering – the activity (SETA), an activity that can be, and is being, performed by anyone. Section 2 compresses 15 years of research into the nature of systems engineering by summarising the nature of two different systems engineering paradigms, SETR and SETA.