THE GREATEST URDU STORIES EVER TOLD Also by Muhammad Umar Memon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Expect with My New Mattress

What To Expect With a New Set of Bedding Expect An Adjustment Period. Just as your new dress shoes take some time to feel good, your new mattress might take some time for your body to become adjusted. This is especially true if you are changing from a very old bed set, a damaged bed set, or a poor quality bed set. This is also true if you are changing “comfort” levels, for example moving from a firm to a new fluffy pillow top mattress. It can take days or weeks for your body to adjust to a new mattress. Slight Comfort Impressions Are Normal. You can expect your mattress to develop slight indentations called “body impressions” as soon as you start sleeping on it. These slight indentations are normal and are the result of the quilt and upholstery layers settling and conforming to your individual body. As these layers compress, the mattress will actually improve in performance. True sagging resembles the dipping look of a hammock in which the dip measures greater than 1 1/2 inches. While slight body impressions are normal, they are usually not greater than 1 1/2 inches in depth and are therefore not reason to exchange your mattress under warranty. Although most mattresses now only have one sleep surface, your mattress may benefit in comfort and durability if it is rotated regularly (clockwise). Visible Ridge Down The Middle Is Normal. When two people share a bed, they usually each sleep on one side therefore settling the layers of comfort on each side. Often times, there is a visible ridge down the middle of a king or queen bed where the comfort layers have not been compressed. -

W2990 Sleigh Toddler

Toddler bed (2990) - Assembly and Operation Manual Congratulations on purchasing a MDB Family product. This bed will provide many years of service if you adhere to the following guidelines for assembly, maintenance and operation. This bed is for residential use only. Any institutional use is strictly prohibited. Please be sure to follow the instructions for proper assembly. Use a Phillips head screwdriver for the assembling of the bed. Do not use power screwdrivers. All of our toddler beds are made from natural woods. Please understand that natural woods have color variations which are the result of nature and are not defects in workmanship. DO NOT SUBSTITUTE PARTS. ALL MODELS HAVE THE SAME QUANTITY OF PARTS AND HARDWARE. YOUR MODEL MAY LOOK DIFFERENT FROM THE ONE ILLUSTRATED DUE TO STYLISTIC VARIATIONS. Please read the Caution and Warning Statements insert before using your bed. revised 29DEC2011 page 1 PARTS C. Slats (10) D. Center slat A. Headboard B. Footboard E. Left side rail F. Right side rail HARDWARE G. 2” Allen head bolt (4) H. Barrel nut (14) K. Allen wrench J. 3 1/2” Allen head bolt (10) L. Lock washer (10) READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE ASSEMBLING BED. WARNING: KEEP THE MANUAL FOR FUTURE USE. page 2 STEP 1. Fit the dowels of the slats (C) into the pre-drilled holes of the E left side rail (E). Attach the center slat (D) to the left side rail (E) using two 2” Allen head bolts (G) and two barrel nuts (H). C E G C G D H STEP 2. Attach the right side rail (F) in the same manner as step 1. -

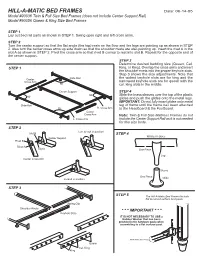

HILL-A-MATIC BED FRAMES Date: 06-14-05 Model #90036 Twin & Full Size Bed Frames (Does Not Include Center Support Rail) Model #90056 Queen & King Size Bed Frames

HILL-A-MATIC BED FRAMES Date: 06-14-05 Model #90036 Twin & Full Size Bed Frames (does not include Center Support Rail) Model #90056 Queen & King Size Bed Frames STEP 1 Lay out bed rail parts as shown in STEP 1. Swing open right and left cross arms. STEP 2 Turn the center support so that the flat angle (the top) rests on the floor and the legs are pointing up as shown in STEP 2. Also turn the center cross arms up side down so that the shoulder rivets are also pointing up. Insert the rivet A in the slot A as shown in STEP 2. Pivot the cross arm so that rivet B comes to rest into slot B. Repeat for the opposite end of the center support. STEP 3 Determine desired bedding size (Queen, Cal. STEP 1 King, or King). Overlap the cross arms and insert the shoulder rivets into the proper keyhole slots. Step 3 shows the size adjustments. Note that the widest keyhole slots are for king and the Center Slide Rail Cross Arm narrowest keyhole slots are for queen with the 900 cal. king slots in the middle. Center Support STEP 4 900 Slide the brass sleeves over the top of the plastic 900 glides and push the glides onto the metal legs. IMPORTANT: Do not fully insert glides onto metal Slide Rail leg of frame until the frame has been attached 900 R. Cross Arm to the Headboard & the Footboard. Center Cross Arm Note: Twin & Full Size Mattress Frames do not L. Cross Arm include the Center Support Rail as it is not needed for this size beds. -

The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan

Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims return to religion-online 47 Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan Kenneth W. Morgan is Professor of history and comparative religions at Colgate University. Published by The Ronald Press Company, New York 1958. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock. (ENTIRE BOOK) A collection of essays written by Islamic leaders for Western readers. Chapters describe Islam's origin, ideas, movements and beliefs, and its different manifestations in Africa, Turkey, Pakistan, India, China and Indonesia. Preface The faith of Islam, and the consequences of that faith, are described in this book by devout Muslim scholars. This is not a comparative study, nor an attempt to defend Islam against what Muslims consider to be Western misunderstandings of their religion. It is simply a concise presentation of the history and spread of Islam and of the beliefs and obligations of Muslims as interpreted by outstanding Muslim scholars of our time. Chapter 1: The Origin of Islam by Mohammad Abd Allah Draz The straight path of Islam requires submission to the will of God as revealed in the Qur’an, and recognition of Muhammad as the Messenger of God who in his daily life interpreted and exemplified that divine revelation which was given through him. The believer who follows that straight path is a Muslim. Chapter 2: Ideas and Movements in Islamic History, by Shafik Ghorbal The author describes the history and problems of the Islamic society from the time of the prophet Mohammad as it matures to modern times. -

A Survey of Urdu Literature, 1850-1975 by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

Conflict, Transition, and Hesitant Resolution: A Survey Of Urdu Literature, 1850-1975 by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi [Note: the definitive version of this article was published in K. M. George, ed., Modern Indian Literature--An Anthology; Volume One: Surveys and Poems (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1992), pp. 420-442.] For much of North India, the world changed twice in 1857. It first changed in May, when columns of Company soldiers marched into Delhi and proclaimed the end of Company Bahadur's rule. The world changed again in September, by which time it was clear that the brief Indian summer of Indian rule was decisively over. If the first change was violent and disorderly, it was also fired by a desperate hope, and a burning anger. Anger had generated hope--hope that the supercilious and brutal foreigner, who understood so little of Indian values and Indian culture, could still be driven out, that he was not a supernatural force, or an irrevocable curse on the land of Hindustan. The events of 1857-1858 drove the anger underground, and destroyed the hope. The defeat, dispersal, and death of the rebels signalled the end of an age, and the ushering in of a new order. It was an order which was essentially established by force, but which sought to legitimate itself on the grounds of moral superiority. It claimed that its physical supremacy resulted from its superior intellectual apparatus and ethical code, rather than merely from an advantage in numbers or resources. It was thus quite natural for the English to try to change Indian society from both the inside and outside. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial Celebrations)

© Nischint Bhatnagar Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial celebrations) Born September 01, 1915 at Lahore Cantonment, Sadar Bazaar; Died November 11, 1984 in Bombay. His father, S. Hira Singh Bedi was a Postmaster. He was very fond of Urdu and Farsi. His Mother Smt. Sewa Dei was from a Hindu family and very knowledgeable of Sikh and Hindu religion, the stories of the Puranas and also of Muslim lore. She was a wonderful painter and had covered the walls of the house with scenes from the Mahabharata. The house had a mixed culture of Sikhism and Hinduism and father took part in Muslim festivals enthusiastically. Rajinder’s imaginative skills were developed under their fond care, storytelling and father’s witticisms. He matriculated from the S.B.B.S. Khalsa High School, Lahore and joined the DAV College, Lahore. He passed his Intermediate but could not go for BA studies. Mother had died March 28, 1933 of tuberculosis and father wanted him to marry so that there may be a caregiver in the family. He left his studies and joined the postal service as a clerk in 1933. He got married in 1934. His wife’s maiden name was Soman and married name Satwant Kaur. His first son, Prem, was born in 1935. Father who was then working as Postmaster in Toba Tek Singh came to Lahore to celebrate the arrival of a grandson but died there on August 31, 1935. The whole burden for fending for his family, his two brothers and sister fell on him and Satwant. The son Prem also passed away in 1936. -

Gurpurab Greetings

www.punjabadvanceonline.com Gurpurab Greetings Sri Guru Nanak Dev's 550th birth anniversary (Nov 23) 2 Punjab Advance August 2016 Editorial The Boy Who Cried Wolf is one of my favourite Aesop's Fables, I don’t know why but it appears to fit into the current Delhi smog tale. For the third year running Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal repeated his ‘stubble burning’ cries. His hat-trick of alarm calls remind me of the shepherd boy who cried wolf, with no wolf around. Initially the people came to his aid, but when he repeated the cries no one turned up and ultimately he fell vic - tim to his own follies. The Punjab Chief Minister Capt Amarinder Singh has been quick in ridi - culing the nonsensical claim of his Delhi counterpart asking him to stop in - dulging in political theatrics and to check the facts before shooting from the mouth. He has trashed as yet another attempt by the Delhi Chief Min - ister to divert public attention for his own government’s abysmal failure on all counts. As per data provided by private and government agencies stubble burn - ing accounts for a bare 4 per cent of the total smog enveloping the National Capital Region. More than 80 per cent of the deadly cocktail of soot, smoke, metals, nitratres, sulphates is the result of the local activities like vehicu - lar traffic, industrial pollution, construction activity, garbage burning etc. Vehicular pollution alone contributes 40 per cent of the total pollution level. According to the latest data released by the Ministry of Earth Sciences and the Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) crop burning, which lasts for about 15-20 days during this period, contributes just 4 per cent of the total pollution in Delhi-NCR on an average. -

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls Upto 31-01-2018

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls upto 31-01-2018 S.No. Name/ Father Name Qualification Address Date of Registration Validity Registration Number 1. Dr. Yash Pal Bhandari S/o L.M.S.F. 1948 81, Vijay Nagar, Jalandhar 12.04.1948 45 22.10.2018 Sh. Ram Krishan M.B.B.S. 1961 M.D. 1965 2. Dr. Balwant Singh S/o LSMF 1952 1814, Maharaj nagar, Near Gate No.3, 28.10.1952 3266 17.03.2021 Sh. Suhawa Singh M.B.B.S. 1964 of P.A.U., Ludhiana 3. Dr. Kanwal Kishore Arora S/o M.B.B.S. 1952 392, Adarsh Nagar Jalandhar 15.12.1952 3312 09.03.2019 Sh. Lal Chand Pasricha 4. Dr. Gurbax Singh S/o LSMF 1952 B-5/442, Kulam Road, Tehsil 11.03.1953 3396 23.04.2019 Sh. Mangal Singh M.B.B.S. 1956 Nawanshahr Distt. SBS Nagar D.O. 1957 5. Dr. Jawahar Lal Luthra L.S.M.F. 1953 H.No.44, Sector 11-A, Chandigarh 27.10.1953 3555 07.10.2018 M.B.B.S. 1956 M.S. (Ophth.) 1970 6. Dr. Kirpal Kaur M.B.B.S. 1953 490, Basant Avenue, Amritsar 09.12.1953 3599 31.03.2019 M.D. 1959 7. Dr. Harbans Kaur Saini L.S.M.F. 1954 Railway Road, Nawan Shahr Doaba 31.05.55 4092 29.01.2019 8. Dr. Baldev Raj Bhateja L.S.M.F. 1955 Raj Poly Clinic and Nursing Home, Pt. 08-06-1955 4106 09.10.2018 Jai Dayal St., Muktsar. -

Pdf APPEAL (October 2005)

PAKISTANIAAT A Journal of Pakistan Studies Volume 1, Number 1, 2009 ISSN 1946-5343 http://pakistaniaat.org Sponsored by the Department of English, Kent State University Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies ISSN 1946-5343 Pakistaniaat is a refereed, multidisciplinary, open-access academic journal, published semiannually in June and December, that offers a forum for a serious academic and cre- ative engagement with various aspects of Pakistani history, culture, literature, and politics. Editorial Team Proof Readers Andrew Smith, Florida State University. Editor Elizabeth Tussey, Kent State University. Masood Raja, Kent State University, United Benjamin Gundy, Kent State University. States. Editorial Board Section Editors Tahera Aftab, University of Karachi. Masood Raja, Kent State University. Tariq Rahman, Quaid-e-Azam University, Deborah Hall, Valdosta State University, Pakistan. United States. Babacar M’Baye, Kent State University David Waterman, Université de La Ro- Hafeez Malik, Villanova University. chelle, France. Mojtaba Mahdavi, University of Alberta, Yousaf Alamgiriam, Writer and Independent Edmonton. Scholar, Pakistan Pervez Hoodbhoy, Quaid-e-Azam Univer- sity, Pakistan. Layout Editor Robin Goodman, Florida State Universi- Jason W. Ellis, Kent State University. ty. Katherine Ewing, Duke University. Copy Editors Muhammad Umar Memon, University of Jenny Caneen, Kent State University. Wisconsin, Madison. Swaralipi Nandi, Kent State University. Fawzia Afzal-Khan, Montclair State Univ- Kolter Kiess, Kent State University. eristy. Abid Masood, University of Sussex, United Kamran Asdar Ali, University of Texas, Kingdom. Austin. Robin L. Bellinson, Kent State University. Amit Rai, Florida State University. Access Pakistaniaat online at http://pakistaniaat.org. You may contact the journal by mail at: Pakistaniaat, Department of English, Kent State Univeristy, Kent, OH 44242, United States, or email the editor at: [email protected]. -

Travel, Travel Writing and the "Means to Victory" in Modern South Asia

Travel, Travel Writing and the "Means to Victory" in Modern South Asia The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Majchrowicz, Daniel Joseph. 2015. Travel, Travel Writing and the "Means to Victory" in Modern South Asia. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467221 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Travel, Travel Writing and the "Means to Victory" in Modern South Asia A dissertation presented by Daniel Joseph Majchrowicz to The Department of NELC in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Language and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Daniel Joseph Majchrowicz All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Ali Asani Daniel Joseph Majchrowicz Travel, Travel Writing and the "Means to Victory" in Modern South Asia Abstract This dissertation is a history of the idea of travel in South Asia as it found expression in Urdu travel writing of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Though travel has always been integral to social life in South Asia, it was only during this period that it became an end in itself. The imagined virtues of travel hinged on two emergent beliefs: that travel was a requisite for inner growth, and that travel experience was transferable.