Rapid Assessment of Aama Programme Roundxi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

COVID19 Reporting of Naukunda RM, Rasuwa.Pdf

स्थानिय तहको विवरण प्रदेश जिल्ला स्थानिय तहको नाम Bagmati Rasuwa Naukunda Rural Mun सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृत पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृतसुमित कुमार संग्रौला 9823290882 ६ गोसाईकुण्ड गाउँपालिका जिम्मेवार पदाधिकारीहरू क्र.स. पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 प्रमुख प्रशासकीय अधिकृतनवदीप राई 9807365365 १३ विराटनगर, मोरङ 2 सामजिक विकास/ स्वास्थ्यअण प्रसाद शाखा पौडेल प्रमुख 9818162060 ५ शुभ-कालिका गाउँपालिका, रसुवा 3 सूचना अधिकारी डबल बहादुर वि.के 9804669795 ५ धनगढी उपमहानगरपालिका, कालिका 4 अन्य नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 ६ पिपरा गाउँपालिका, महोत्तरी 5 6 n विपद व्यवस्थापनमा सहयोगी संस्थाहरू क्र.स. प्रकार नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 n ारेाइन केको ववरण ID ारेाइन केको नाम वडा ठेगाना केन्द्रको सम्पर्क व्यक्तिसम्पर्क नं. भवनको प्रकार बनाउने निकाय वारेटाइन केको मता Geo Location (Lat, Long) Q1 गौतम बुद्ध मा.वि क्वारेन्टाइन स्थल ३ फाम्चेत नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 विध्यालय अन्य (वेड संया) 10 28.006129636870693,85.27118702477858 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q11 Qn भारत लगायत विदेशबाट आएका व्यक्तिहरूको विवरण अधारभूत विवरण ारेाइन/अताल रफर वा घर पठाईएको ववरण विदेशबाट आएको हो भने मात्र कैिफयत ID नाम, थर लिङ्ग उमेर (वर्ष) वडा ठेगाना सम्पर्क नं. -

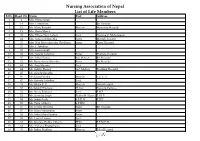

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

Bangad Kupinde Municipality Profile 2074, Salyan All.Pdf

aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsf aguf8 s'lk08] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] sfof{no ;Nofg, ^ g+= k|b]z, g]kfn gu/ kfZj{lrq @)&$ c;f/ b'O{ zAb o; gu/kflnsf cGtu{t /x]sf ;fljs b]j:yn, afd], 3fFem/Llkkn, d"nvf]nf uf=lj=;= df k|rlnt aGuf8L ;F:s[lt / ;Nofg lhNnfnfO{ g} /fli6«o tyf cGt/f{li6«o ¿kdf lrgfpg ;kmn s'lk08]bxsf] ;+of]hgaf6 gfdfs/0f ul/Psf] aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsfsf] klxnf] k|sflzt b:tfj]hsf] ¿kdf cfpg nfu]sf] kfZj{lrq 5f]6f] ;dod} tof/L ug{ kfpFbf cToGt} v';L nfu]sf] 5 . /fHosf] k'g;{+/rgfsf] l;nl;nfdf :yflkt o; gu/kflnsfsf] oyfy{ ljBdfg cj:yf emNsfpg] kfZj{lrq tof/Ln] gu/sf] ljsf;sf] jt{dfg cj:yfnO{ lrlqt u/]sf] 5 . o:tf] lrq0fn] cfufdL lbgdf xfdLn] th'{df ug'{kg]{ gLlt tyf sfo{qmdx¿nfO{ k|fyldsLs/0f u/L xfdLnfO{ pknAw ;Lldt >f]t tyf ;fwgsf] clwstd ;b'kof]u u/L gu/ ljsf;nfO{ ult k|bfg ug{ cjZo klg ;xof]u k'¥ofpg] cfzf tyf ljZjf; lnPsf] 5' . o; cWoog k|ltj]bgn] k|foM ;a} If]q tyf j:t'ut oyfy{nfO{ ;d]6\g k|of; u/]sf] ePtfklg ;Lldt ;do tyf ;|f]t ;fwgsf] ;Ldfleq ul/Psf] cWoog cfkm}df k"0f{ x'g ;Sb}g . o;nfO{ ;do ;Gbe{cg';f/ kl/is[t / kl/dflh{t ug]{ bfloTj xfd|f] sfFwdf cfPsf] dxz'; xfdL ;a}n] ug'{ kg]{ x'G5 . of]hgfj4 ljsf;sf] cfwf/sf] ¿kdf /xg] of] kfZj{lrq ;dod} tof/ ug{ nufpg] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] ;Dk"0f{ l6d, sfo{sf/L clws[t tyf cGo j8f txdf dxTjk"0f{ lhDd]jf/L k'/f ug]{ sd{rf/L Pj+ lgjf{lrt hgk|ltlglw nufot tYofÍ pknAw u/fpg] ;Dk"0f{ ljifout sfof{no, ;+3;+:yf tyf cGo ;a}df gu/kflnsfsf] tkm{af6 cfef/ k|s6 ug{ rfxG5' . -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Whitewater Packrafting in Western Nepal a Senior Expedition Proposal for the SUNY Plattsburgh Expeditionary Studies Program ______

Whitewater Packrafting in Western Nepal A Senior Expedition Proposal for the SUNY Plattsburgh Expeditionary Studies Program ______________________________________________________________________ Ted Tetrault Professor Gerald Isaak EXP435: Expedition Planning December 1, 2016 Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 2. Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………….... 7 3. Design and Methodology…………………………………………………………………… 16 4. Risk Management……………………………………………………………………………. 29 5. References……………………………………………………………………………………. 38 6. Appendix A: Expedition Field Manual…………………………………………………… 39 7. Appendix B: Related Maps and Documents……………………………………………. 42 8. Appendix C: Budget………………………………………………………………………… 44 9. Appendix D: Gearlist………………………………………………………………………... 47 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________________________ This expedition plan outlines a whitewater packrafting trip on the Bheri and Seti Karnali rivers in western Nepal that will serve as my capstone project for the Bachelor’s of Science in the Expeditionary Studies program at SUNY Plattsburgh. While these rivers will count as my own personal senior expedition, the trip in its entirety will also include the running of the Sun Kosi river in eastern Nepal, and that plan can be found in a separate document authored by Alex LaLonde as that segment will be serving as his capstone project for the same program. Adventure travel expeditions give us the -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (Muan) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN)

Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (MuAN) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden European Sverige Union "This document has been financed by the Swedish "This publication was produced with the financial support of International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of does not necessarily share the views expressed in this MuAN, NARMIN, ADCCN and UCLG and do not necessarily material. Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the reflect the views of the European Union'; author." Publication Date June 2020 Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal (MuAN) National Association of Rural Municipality in Nepal (NARMIN) Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden Sverige European Union Expert Services Dr. Dileep K. Adhikary Editing service for the publication was contributed by; Mr Kalanidhi Devkota, Executive Director, MuAN Mr Bimal Pokheral, Executive Director, NARMIN Mr Krishna Chandra Neupane, Executive Secretary General, ADCCN Layout Designed and Supported by Edgardo Bilsky, UCLG world Dinesh Shrestha, IT Officer, ADCCN Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... -

An Inventory of Nepal's Insects

An Inventory of Nepal's Insects Volume III (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera & Diptera) V. K. Thapa An Inventory of Nepal's Insects Volume III (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera& Diptera) V.K. Thapa IUCN-The World Conservation Union 2000 Published by: IUCN Nepal Copyright: 2000. IUCN Nepal The role of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in supporting the IUCN Nepal is gratefully acknowledged. The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for education or non-profit uses, without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. IUCN Nepal would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication, which uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purposes without prior written permission of IUCN Nepal. Citation: Thapa, V.K., 2000. An Inventory of Nepal's Insects, Vol. III. IUCN Nepal, Kathmandu, xi + 475 pp. Data Processing and Design: Rabin Shrestha and Kanhaiya L. Shrestha Cover Art: From left to right: Shield bug ( Poecilocoris nepalensis), June beetle (Popilla nasuta) and Ichneumon wasp (Ichneumonidae) respectively. Source: Ms. Astrid Bjornsen, Insects of Nepal's Mid Hills poster, IUCN Nepal. ISBN: 92-9144-049 -3 Available from: IUCN Nepal P.O. Box 3923 Kathmandu, Nepal IUCN Nepal Biodiversity Publication Series aims to publish scientific information on biodiversity wealth of Nepal. Publication will appear as and when information are available and ready to publish. List of publications thus far: Series 1: An Inventory of Nepal's Insects, Vol. I. Series 2: The Rattans of Nepal. -

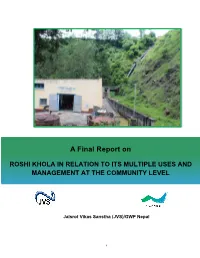

A Final Report On

Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha A FinalKathmandu Report on ROSHI KHOLA IN RELATION TO ITS MULTIPLE USES AND MANAGEMENT AT THE COMMUNITY LEVEL December 2016 Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha (JVS)/GWP Nepal i Disclaimer The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the institution. ii Foreword This research was part of WACREP activity of Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha (JVS)/GWP Nepal. JVS/GWP Nepal highly appreciates the contribution of Mr. Prakash Gaudel for conducting the research. Our sincere gratitude also goes to Mr. Batu K. Uprety and Dr. Vijaya Shrestha for reviewing the draft by providing valuable suggestions. JVS/GWP Nepal also acknowledges the contribution from Mr.Tejendra GC and Ms. Anju Air during the preparation of this publication. Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha (JVS)/GWP Nepal iii Acronyms DDC : District Development Committee DHM : Department of Hydrology and Meteorology DoED : Department of Electricity Development GoN : Government of Nepal GWP : Global Water Partnership HEP : Hydroelectric Project JVS : Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha KVIWSP : Kavre Valley Integrated Water Supply Project MoEn : Ministry of Energy MoI : Ministry of Irrigation MoUD : Ministry of Urban Development MW : Megawatt NEA : Nepal Electricity Authority NGO : Non-governmental Organization NPC : National Planning Commission NWSC : Nepal Water Supply Corporation VDC : Village Development Committee WUA : Water Users Association iv Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................