State Building and Exit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Balkans | 65

westeRn BalKans | 65 3.4 Mission Reviews Western Balkans he Western Balkans have been a testing-ground Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) and Kosovo. T for a huge range of political missions since the Each of these figures also has responsibility for early 1990s. These have ranged from light-weight some sort of field presence, although these are civilian monitoring missions meant to help contain not straightforward European political missions. the Yugoslav wars to long-serving presences tasked The EUSR in BiH also serves as the Interna- with promoting good governance, fair elections, tional High Representative, answering to a Peace minority rights and economic rehabilitation. Implementation Council of fifty-five countries and These long-term presences were usually organizations.1 The EUSR in Kosovo is similarly deployed to support or replace peacekeepers. double-hatted as the International Civilian Repre- The large military forces that stabilized the region sentative (ICR, answering to a Steering Group of have now downsized, while some international 28 countries that recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty). civilian missions are likely to remain in place for a The EUSR in FYROM has also acted as the head considerable time. of the European Commission’s delegation there Today, two organizations have prominent since late 2005. political missions in the Balkans. The Organization In addition to the OSCE and EU, the UN has for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) a residual presence in the Western Balkans. The maintains field presences in Albania and all the for- UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo mer constituent parts of Yugoslavia except Slovenia (UNMIK), having had executive authority and a (its presence in Croatia, however, is now an office in large civilian police arm from 1999 to 2008, has an Zagreb and will not be discussed here). -

Leaflet Policy Forum on Eusrs

Policy Forum “The role and achievements of EU Special Representatives in EU foreign policy” Friday, 15 June 2012, 11.40h – 14.00h Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel Since 1996, the Council of the EU has deployed over 40 EU Special Representatives (EUSRs) to various crisis regions where they are involved in the European Union’s conflict resolution efforts. They also contribute to the formulation of the EU’s policies, to the coordination of EU actors 'on the ground' and to the EU’s cooperation with other international actors in the field. While Catherine Ashton, High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission, initially intended to phase out the EUSRs, new officeholders have been appointed in 2011 and 2012. This demonstrates the added value of the EUSRs as a rather flexible tool in EU foreign policy. The Policy Forum focuses on the role and the achievements of the EUSRs in the implementation of the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy in the past sixteen years. It looks at their contribution to conflict resolution, their interplay with other diplomats, their institutional setting within the External Action Service and their relations with the European Commission and the EU delegations. Speakers and discussants include acting and former EUSRs and officials from the External Action Service: § Ambassador Philippe Lefort (EU Special Representative for the South Caucasus and the crisis in Georgia) § Ambassador Pieter Feith (International Civilian -

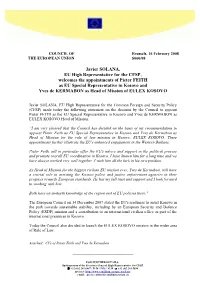

Javier SOLANA

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 16 February 2008 THE EUROPEAN UNION S060/08 Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the CFSP, welcomes the appointments of Pieter FEITH as EU Special Representative in Kosovo and Yves de KERMABON as Head of Mission of EULEX KOSOVO Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) made today the following statement on the decision by the Council to appoint Pieter FEITH as the EU Special Representative in Kosovo and Yves de KERMABON as EULEX KOSOVO Head of Mission. “I am very pleased that the Council has decided on the basis of my recommendation to appoint Pieter Feith as EU Special Representative in Kosovo and Yves de Kermabon as Head of Mission for the rule of law mission in Kosovo, EULEX KOSOVO. These appointments further illustrate the EU's enhanced engagement in the Western Balkans. Pieter Feith will in particular offer the EU's advice and support in the political process and promote overall EU coordination in Kosovo. I have known him for a long time and we have always worked very well together. I wish him all the luck in his new position. As Head of Mission for the biggest civilian EU mission ever, Yves de Kermabon, will have a crucial role in assisting the Kosovo police and justice enforcement agencies in their progress towards European standards. He has my full trust and support and I look forward to working with him. Both have an in-depth knowledge of the region and of EU policies there." The European Council on 14 December 2007 stated the EU's readiness to assist Kosovo in the path towards sustainable stability, including by an European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) mission and a contribution to an international civilian office as part of the international presences in Kosovo. -

Why EU Promotion Is at Odds with Successful

EUC Working Paper No. 10 Working Paper No. 10, September 2012 Why EU promotion is at odds with successful crisis management: Public relations, news coverage, and the Aceh Monitoring Mission Stephanie Anderson Photo © Aceh Monitoring Mission ABSTRACT The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and its accompanying Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions can be tools used to increase the international profile of the European Union. Nevertheless, CSDP missions garner little news coverage. This article argues that the very nature of the missions themselves makes them poor vehicles for EU promotion for political, institutional, and logistical reasons. By definition, they are conducted in the middle of crises, making news coverage politically sensitive. The very act of reporting could undermine the mission. Institutionally, all CSDP missions are intergovernmental, making press statements slow, overly bureaucratic, and of little interest to journalists. Logistically, the missions are often located in remote, undeveloped parts of the world, making it difficult and expensive for European and international journalists to cover. Moreover, these regions in crisis seldom have a thriving, local free press. Using the Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) as a case study, the author concludes that although a mission may do good, CSDP missions cannot fulfil the political function of raising the profile of the EU. The EU Centre in Singapore is a partnership of 13 EUC Working Paper No. 10 Why EU promotion is at odds with how the very nature of CSDP missions undermines successful crisis management: Public their use as a political promotion tool. relations, news coverage, and the Aceh Visibility and the CSDP: Increasing the EU’s Monitoring Mission International Prestige and Support among its Citizens2 1 STEPHANIE ANDERSON The EU’s foreign and security policy is supposed to increase its profile both at home and abroad. -

Whole-Of-Society Peacebuilding

Whole-of-Society Peacebuilding Edited by Mary Martin and Vesna Bojicic-Dzelilovic First published 2019 ISBN13: 978-0-367-23688-5 Chapter 6 Coordinating international interventions in complex settings. An analysis of the EU peace and state-building efforts in post-independence Kosovo Chris van der Borgh, Puck le Roy and Floor Zweerink (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) LONDON AND NEW YORK Coordinating international interventions in complex settings. An analysis of the EU peace and state-building efforts in post-independence Kosovo Chris van der Borgh, Puck le Roy and Floor Zweerink ABSTRACT This paper assesses coordination as a salient capability of interna- tional interventions in complex settings characterised by weak states, the dominance of political elites whose interest in reforms is questionable and multiple local and international stakeholders. It focuses on the challenge of integrating a range of national and international actors and multiple policy domains, assessing this operational capability in terms of a Whole-of-Society approach. Using the example of the EU’s intervention in Kosovo through the mechanisms of the EULEX mission, and the EU-facilitated Dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo, the paper argues that the EU’s impact in Kosovo was weakened by its limited ability to include and engage a broad range of local stakeholders. While a Whole-of-Society approach could address this weakness, the paper also argues that a better understanding of the context-specific opportunities and limitations placed on international organisa- tions like the EU is needed. Introduction Over the past 20 years, the EU has transformed from an actor with limited leverage to a major player in Kosovo. -

Aldo Ajello Was Appointed EU Special Envoy for the African Great

Pieter Feith was appointed appointed European Union Special Representative in Kosovo on 4 February 2008. His current mandate, which runs until 30 April 2011, includes the tasks of offering the EU's advice and support in the political process and of promoting overall EU political coordination in Kosovo, thereby implementing the policy objectives of the EU in Kosovo. This includes the aim of developing a stable, viable, peaceful democratic and multi- ethnic Kosovo. Mr Feith is also "doubled-hatted" as the International Civilian Representative. 1. Pieter Feith, EU Special Representative in Kosovo Mr Pieter Feith EUSR website Mission Statement - International Support for a European future The objective of the EU in Kosovo is to support and assist the Kosovo authorities in developing a stable, viable, peaceful and multi-ethnic society in Kosovo, cooperating peacefully with its neighbours. These aims are high and I believe they are rightly so. The EU will offer a multifaceted approach in assisting Kosovo's security and development. We will make use of all our political, financial and security mechanisms in a unified and coherent manner with the aim of reaching this objective. My tasks will be to assist the political process and to promote coordination of all these efforts, including by providing local political guidance to the EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo. I believe that the future of Kosovo is of immense importance to the European Union and in my role as EU Special Representative in Kosovo I will tirelessly assist the local authorities by offering the EU's advice and support. My aim is a Kosovo that is committed to the rule of law and to the protection of minorities and of cultural heritage. -

Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2008

United Nations S/2008/106* Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2008 Original: English Letter dated 18 February 2008 from the Secretary-General to the President of the Security Council I have received today the attached letter from Mr. Javier Solana, European Union High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, informing me of the decision by the European Union to deploy a rule of law mission to Kosovo within the framework provided by resolution 1244 (1999), and of the decision by the European Union to appoint a European Union Special Representative for Kosovo. I should be grateful if you would bring this document to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) Ban Ki-moon * Reissued for technical reasons. 08-24262* (E) 200208 *0824262* S/2008/106 Annex Letter dated 18 February 2008 from the Secretary-General and High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations [Original: French] I have the honour to inform you that, on 4 February, the Council of the European Union, on the basis of the conclusions of the European Council of 14 December, adopted the Joint Action and the concept of operations enabling the deployment of the European Union operation in Kosovo. This operation, relating to the rule of law (essentially police and justice), aims to ensure the maintenance of an international civilian presence within the framework of Security Council resolution 1244 (1999) and to contribute as effectively as possible to the maintenance of regional peace and security. -

Weekly Newsletter07 180208 View

OMCT-Europe Weekly Newsletter 2008 N°7, 12.02- 18.02.2008 SUMMARY REGIONS: AFRICA Sudan Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the CFSP, condemns the escalating violence in Darfur (14/02/2008) AMERICAS ASIA Pakistan MEPs to observe elections in Pakistan (14/02/2008) Declaration by the Presidency on behalf of the European Union on the general elections in Pakistan (15/02/2008) EUROPE (OUTSIDE OF UE ) AND CIS Uzbekistan Declaration by the Presidency on behalf of the European Union on the release of human rights defenders in Uzbekistan (14/02/2008) Kosovo ► Javier Solana, EU High Representative for the CSP welcomes the appointments of Pieter Feith as EU Special Representative in Kososvo and Yves de Kermabon as Head of Mission of EULEX Kosovo ( 16/02/2008) ► Council establishes an EU Rule of Law Mission and appoints an EU Special representative( 16/02/2008) ► Javier Solana, EU High Representative for the CFSP on the latest developments in Kosovo (17/02/2008), MAGHREB AND MIDDLE EAST THEMATIC : FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVES JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS EXTERNAL RELATIONS & DEVELOPMENT-RELATED ISSUES EU / UN REFORM MISCELLANEOUS Fundamental Rights Agency Civil Liberties Committee backs Morten Kjaerum for director of the Funadamental Rights Agency (12/02/2008) IMPORTANT COMING MEETINGS EU - THIRD COUNTRY MEETINGS EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT MEETINGS Committee on Development February, 26, 27, 2008 Committee on Foreign Affairs February, 18, 2008 (Strasbourg) Subcommittee on Human Rights February, 27, 28, 2008 Subcommittee on security and defence February, -

CSDP Missions and Operations- Lessons Learned

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES OF THE UNION DIRECTORATE B POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY CSDP MISSIONS AND OPERATIONS: LESSONS LEARNED PROCESSES Abstract The first Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission was launched in 2003. Since then the EU has launched 24 civilian missions and military operations. Despite the tendency of military operations to attract more attention, the majority of CSDP (Common Security and Defence Policy) interventions have been civilian missions. Since the beginning the actors involved in CSDP recognised the need to learn from the different aspects of missions and operations. The tools and methodologies to guarantee a successful learning process have evolved over time together with the evolution of CSDP. This study represents a first stock-taking exercise of the lessons learned processes at the EU level. The study is divided in three major components. The first component looks at the available literature on the subject of knowledge management with regard to CSDP missions and operations. The study then draws upon short case-studies from the 21 missions and operations to-date with a specific focus on the lessons identified and (possibly) learned in practice. The study concludes with a number of recommendations targeted at how the lessons learning processes could be improved including specific recommendations on the role of the European Parliament. EXPO/B/SEDE/FWC/2009-01/Lot6/16 APRIL 2012 PE 457.062 EN This study was requested by the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Security and Defence AUTHORS: -

Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the CFSP, Welcomes the Appointment of Pieter FEITH As EU Special Representative in Kosovo

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 16 February 2008 THE EUROPEAN UNION S060/08 Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the CFSP, welcomes the appointment of Pieter FEITH as EU Special Representative in Kosovo Javier SOLANA, EU High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) made today the following statement on the decision by the Council to appoint Pieter FEITH as the EU Special Representative in Kosovo. “I am very pleased that the Council has decided on the basis of my recommendation to appoint Pieter Feith as EU Special Representative in Kosovo. This appointment further illustrates the EU's enhanced engagement in the Western Balkans. Pieter Feith will in particular offer the EU's advice and support in the political process and promote overall EU coordination in Kosovo. I have known him for a long time and we have always worked very well together. I wish him all the luck in his new position. He has an in-depth knowledge of the region and of EU policies there." The European Council on 14 December 2007 stated the EU's readiness to assist Kosovo in the path towards sustainable stability, including by an European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) mission and a contribution to an international civilian office as part of the international presences in Kosovo. Today the Council also decided to launch the EULEX KOSOVO mission in the wider area of Rule of Law. Attached: CV of Pieter Feith ______________________________ FOR FURTHER DETAILS: Spokesperson of the Secretary General, High Representative for CFSP +32 (0)2 281 6467 / 5150 / 5151 / 8239 +32 (0)2 281 5694 internet: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/solana e-mail: [email protected] Pieter Cornelis FEITH Place and date of birth: Rotterdam, 9 February 1945 Nationality: Dutch Education M.A. -

37Th Asser Colloquium on European Law

T.M.C. ASSER INSTITUUT 37th Asser Colloquium on European Law The European Union and International Crisis Management: Legal and Policy Aspects 11 – 12 October 2007 Paleiskerk, The Hague, The Netherlands T.M.C. Asser Instituut (est. 1965), a renowned interuniversity centre in the fields of international and European law, organized the first sessions of its Colloquium on European Law in 1972. Since then, conferences on European Law have been held annually and quickly gained the reputation of being a major event in the European Union law calendar. www.asser.nl The European Union and International Crisis Management: Legal and Policy Aspects Programm During the 1990’s, the European Union stood by and watched EU has been rather successful in carrying out its new tasks as an the Balkans burn. Reliance upon US diplomacy and NATO's international crisis manager. Cleverly, it has sought the cooperation military power to put the fire out condemned the EU to paying of other 'security' organisations to back up diplomacy by military the bills for reconstruction, while not moving the emphasis to force in potentially highly inflammable situations. conflict prevention and crisis management. Frustration at such inadequacies and calls for change by others led France and the The proliferation of the EU's institutional and operational United Kingdom, the EU Member States that pack the most mechanisms and cooperation with other international military punch, to prod their colleagues at the European Council's organisations to manage crises on its doorstep and farther afield, December 1999 summit at Helsinki in carrying forward work on has led to a whole series of new legal and political questions which the development of the Union's own military and non-military will be addressed at the 37th edition of the T.M.C. -

Ten Years After: Lessons from the EUPM in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2002-2012

European European Union EUPM Union EUPM Institute for Institute for Security Studies Security Studies Ten years after: lessons from the EUPM in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2002-2012 Joint Report January 2013 Edited by Tobias Flessenkemper and Damien Helly Contributors: Edina Bećirević, Maida Ćehajić, Eric Fréjabue, Srećko Latal, Michael Matthiessen, Susan E. Penksa, Dominik Tolksdorf European Union Institute for Security Studies www.iss.europa.eu • [email protected] This report derives from a seminar on ‘The impact of the EU Police Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 2002-2012’, organised jointly by the EU Police Mission (EUPM) and the European Institute for Security Studies, that took place in Sarajevo on 7-8 June 2012. The event marked 10 years of EU civilian crisis management in the Western Balkans and sought to examine the impact of the EUPM in Bosnia and Herzegovina and assess the lessons learned for the future of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The seminar was attended by representatives of the EU institutions (European Commission, EU Delegation in BiH), representatives of the Bosnian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Security and the Parliamentary Assembly as well as academics, think tankers and key players in civil society. The publication was financially supported by the European Union Police Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 [email protected] http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies 2013. All rights reserved.