Social Movements in Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Social Movement and Collective Action Area Exam

Social Movement and Collective Action Area Exam Updated August 2020 Format, Expectations, and Scope Students taking the social movements and collective action area exam are expected to be familiar with the development of the field, the dominant theoretical traditions, the major substantive questions and debates, and the various methodological approaches employed. At the same time, we want to make explicit that the canon upon which this field is based is largely dominated by white cis-men and by Americanist and Eurocentric perspectives. This is a problem not just in the social movements and collective action field, but across sociology more broadly. While the reading list provided here intends to be as inclusive as possible, we face the dilemma of ensuring that students are conversant in foundational works while keeping the list concise. This necessarily limits the inclusivity of the list. We therefore acknowledge this disparity and welcome students to challenge these inequities. Students may do so by providing critiques of canonical texts’ standpoints and biases; by suggesting how inclusivity, marginalized scholars, and under-examined cases can advance the field theoretically, empirically, and methodologically; and by bringing in under-utilized texts. At the same time, any challenge to the canon is going to be ineffective without deep familiarity with the canon. This reading list will therefore provide the foundation for innovation. On the day of the exam, students will answer three out of six questions (students will skip the three questions they least want to answer). Students can bring the reading list (below) and two single-spaced pages of notes to the exam (font must be at least 11 point). -

Downloadhs4016 Social Movements

COURSE OUTLINE Course Code / Title : HS4016 Social Movements Pre-requisites : HS1001 Person and Society HS2001 Classical Social Theory HS2002 Doing Social Research HS3001 Contemporary Social Theory HS3002 Understanding Social Statistics No. of AUs. : 4 Contact Hours : 52 Course Aims From revolutionary movements that overthrew regimes, to women’s movements that have radically altered and continue to challenge gender norms, to contemporary environmental and labor movements that shape the ways governments and businesses behave, social movements have been and continue to be major forces in human history. They account for why power relations are organized in particular ways in given contexts; they shape group identities and boundaries; and they help us understand the limitations and possibilities of social change in our own times and contexts. This course serves as an introduction to the vast and rich research in sociology on this important subject. We will explore social movements through a sociological lens, asking: what are the conditions for their emergence? What are social movement organizations’ and activists’ tactics and strategies, and how do these come about? How do social movements shape the worlds in which we live? Intended Learning Outcomes (ILO) By the end of the course, you should be able to: 1. Discuss the diversity of social movements past and present 2. Evaluate the different ways sociologists have approached the study of social movements 3. Describe the key theories that account for social movements 4. Articulate connections -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

The Sociology of Social Movements

CHAPTER 2 The Sociology of Social Movements CHAPTER OBJECTIVES • Explain the important role of social movements in addressing social problems. • Describe the different types of social movements. • Identify the contrasting sociological explanations for the development and success of social movements. • Outline the stages of development and decline of social movements. • Explain how social movements can change society. 9781442221543_CH02.indd 25 05/02/19 10:10 AM 26 \ CHAPTER 2 AFTER EARNING A BS IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING from Cairo University and an MBA in marketing and finance from the American University of Egypt, Wael Ghonim became head of marketing for Google Middle East and North Africa. Although he had a career with Google, Ghonim’s aspiration was to liberate his country from Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship and bring democracy to Egypt. Wael became a cyber activist and worked on prodemocracy websites. He created a Facebook page in 2010 called “We are all Khaled Said,” named after a young businessman who police dragged from an Internet café and beat to death after Said exposed police corruption online. Through the posting of videos, photos, and news stories, the Facebook page rapidly became one of Egypt’s most popular activist social media outlets, with hundreds of thousands of followers (BBC 2011, 2014; CBS News 2011). An uprising in nearby Tunisia began in December 2010 and forced out its corrupt leader on January 14, 2011. This inspired the thirty-year-old Ghonim to launch Egypt’s own revolution. He requested through the Facebook page that all of his followers tell as many people as possible to stage protests for democracy and against tyranny, corruption, torture, and unemployment on January 25, 2011. -

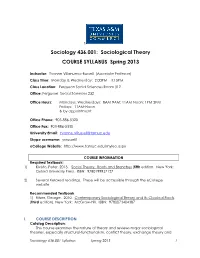

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

Discussion of Frames

10 Frames and Their Consequences Francesca Polletta and M. Kai Ho In 1979, the nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania suffered a partial meltdown and sent hundreds of thousands of residents fleeing as radiation leaked into the atmosphere. The resulting media coverage made “Three Mile Island” into an international symbol of the dangers of nuclear energy, prompted nationwide opposition to nuclear power, and shut down the nuclear industry for more than a decade. Yet, Three Mile Island was not the first accident of its kind. In 1966, the Fermi reactor outside Chicago experienced a partial meltdown followed by a failure of the automatic shut-down system. Officials discussed evacuation plans for area residents as they tried to avert the possibility of a secondary accident. The Fermi accident was no secret: the press was alerted as it was happening. But newspapers, including the New York Times, gave the episode only perfunctory coverage, mainly repeating company spokespeople’s assurances that the reactor would soon be up and running. Why did the Fermi accident not produce the public crisis that Three Mile Island did? Because it was viewed through different frames, says William Gamson (1988). At the time of the Fermi accident, nuclear power was covered by the press mainly in terms of a “faith in progress” frame that viewed nuclear power unequivocally as a boon to technological development and human progress. By Three Mile Island, however, media stories about nuclear power were less confident about nuclear power’s safety and effectiveness. The stage was already set for a critical and alarmist interpretation of the accident. -

SOCY S216 Summer 2019, Session B (July 1 – August 2) Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9:00 - 12:15 AM

Social Movements SOCY S216 Summer 2019, Session B (July 1 – August 2) Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9:00 - 12:15 AM ** Draft Syllabus, Subject to Change ** Instructor Roger Baumann [email protected] Description This course is about how people act collectively to challenge the status quo of powerful political, social, economic, and cultural systems that resist change. Social movements that challenge such systems vary widely in terms of their group identities, social locations, strategies for action, particular demands, and tactics. In order to better understand social movements, we will begin broadly with some key questions: What are social movements and how do we approach the task of defining them? What tools do we need to analyze how movements work? And how can we appreciate how and why some movements succeed in achieving their goals while others apparently fail? In this intensive 5-week summer course, we will focus on one case study per week, using each case to work through a set of concepts that will help us understand particular social movements and how movements work more generally. We will pay attention to how movements operate both inwardly (oriented towards their own members) and outwardly (oriented towards opponents and others). Our primary empirical focus will be on social movements within the United States, but we will also pay close attention to the ways that collective behavior and protest in the U.S. matters globally. Our study of social movements will move back and forth between abstract concepts and particular case studies. Our primary empirical case studies are: 1) The U.S.