Soc 0150 Social Theory Syllabus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

Durkheim and Organizational Culture

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #108-04 June 2004 Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot Cite as: James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot. (2004). “Durkheim and Organizational Culture.” IRLE Working Paper No. 108-04. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/108-04.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 Didier Guillot INSEAD Singapore June , 2004 Prepared for inclusion in Marek Kocsynski, Randy Hodson, and Paul Edwards (editors): Social Theory at Work . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Durkheim and Organizational Culture “The degree of consensus over, and intensity of, cognitive orientations and regulative cultural codes among the members of a population is an inv erse function of the degree of structural differentiation among actors in this population and a positive, multiplicative function of their (a) rate of interpersonal interaction, (b) level of emotional arousal, and (c) rate of ritual performance. ” Durkheim’ s theory of culture as rendered axiomatically by Jonathan Turner (1990) Introduction This paper examines the significance of Emile Durkheim’s thought for organization theory , particular attention being given to the concept of organizational culture. We ar e not the first to take the project on —a number of scholars have usefully addressed the extent and relevance of this giant of Western social science for the study of organization and work. Even so, there is no denying that Durkheim’s name appears with vast ly less frequency in the literature on these topics than is true of Marx and W eber, sociology’ s other founding fathers . -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Jonathan White the Social Theory of Mass Politics

Jonathan White The social theory of mass politics Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: White, Jonathan (2009) The social theory of mass politics. Journal of Politics, 71 (1). pp. 96-112. ISSN 1468-2508 DOI: 10.1017/S0022381608090075 © 2009 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/23528/ Available in LSE Research Online: January 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. WHITE The Social Theory of Mass Politics Journal of Politics 71 (1). 96-112 Jonathan White (LSE) Abstract This paper argues the study of mass politics is currently weakened by its separation from debates in social theory. A preliminary attempt at reconnection is made. The implications of an interpretative turn in social theorising are explored, and the interpretative perspectives of mentalism, intersubjectivism, textualism and practice theory examined in detail, in particular regarding how they and their equivalents in political study differ on units of analysis and how to understand one of the key social practices, language. -

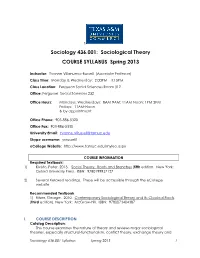

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

Augustine's Contribution to the Republican Tradition

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Peer Reviewed Articles Political Science and International Relations 2010 Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Cornish, Paul J., "Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition" (2010). Peer Reviewed Articles. 10. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science and International Relations at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peer Reviewed Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. article Augustine’s Contribution to the EJPT Republican Tradition European Journal of Political Theory 9(2) 133–148 © The Author(s), 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav [DOI: 10.1177/1474885109338002] http://ejpt.sagepub.com abstract: The present argument focuses on part of Augustine’s defense of Christianity in The City of God. There Augustine argues that the Christian religion did not cause the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 ce. Augustine revised the definitions of a ‘people’ and ‘republic’ found in Cicero’s De Republica in light of the impossibility of true justice in a world corrupted by sin. If one returns these definitions ot their original context, and accounts for Cicero’s own political teachings, one finds that Augustine follows Cicero’s republicanism on several key points. -

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise Max Coleman Oberlin College Sociology Department Senior Honors Thesis April 2014 Table of Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 I. What Is Anomie? Introduction 6 Anomie in The Division of Labor 9 Anomie in Suicide 13 Debate: The Causes of Desire 23 A Sidenote on Dualism and Neuroplasticity 27 Merton vs. Durkheim 29 Critiques of Anomie Theory 33 Functionalist? 34 Totalitarian? 38 Subjective? 44 Teleological? 50 Positivist? 54 Inconsistent? 59 Methodologically Unsound? 61 Sexist? 68 Overly Biological? 71 Identical to Egoism? 73 In Conclusion 78 The Decline of Anomie Theory 79 II. Why Anomie Still Matters The Anomic Nation 90 Anomie in American History 90 Anomie in Contemporary American Society 102 Mental Health 120 Anxiety 126 Conclusions 129 Soldier Suicide 131 School Shootings 135 III. Looking Forward: The Solution to Anomie 142 Sociology as a Guiding Force 142 Gemeinschaft Within Gesellschaft 145 The Religion of Humanity 151 Final Thoughts 155 Bibliography 158 2 To those who suffer in silence from the pain they cannot reveal. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Professor Vejlko Vujačić for his unwavering support, and for sharing with me his incomparable sociological imagination. If I succeed as a professor of sociology, it will be because of him. I am also deeply indebted to Émile Durkheim, who first exposed the anomic crisis, and without whom no one would be writing a sociology thesis. 3 Abstract: The term anomie has declined in the sociology literature. Apart from brief mentions, it has not featured in the American Sociological Review for sixteen years. Moreover, the term has narrowed and is now used almost exclusively to discuss deviance. -

Habermas's Theory of Communicative Action Udc: 316.286:316.257

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 6/2, 1999 pp. 217 - 223 Editor of Special issue: Dragoljub B. Đorđević Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18-547-950 NEW SOCIAL PARADIGM: HABERMAS'S THEORY OF COMMUNICATIVE ACTION UDC: 316.286:316.257 Ljubiša Mitrović Faculty of Philosophy, Niš Abstract. The paper discusses the contribution of J. Habermas to the foundation of a new social paradigm in the form of the communicative action theory. The author first gives a global survey of Habermas's intellectual development, starting from Marx through the critical theory to post-Marxism that Habermas finally left behind since oriented towards convergence and integration of the social action theory, the system theory and the symbolic interactionism theory. Unlike Marx's paradigm of production and social labor as the basic category Marxist theory is built upon, Habermas has built a new paradigm of the communicative action focused upon the communicative mind, communication and rationality as well as the communicative community. The author critically points to the values as well as inner limits of Habermas's theory that reduced a complex and controversial class nature of the society to the "communicative community" thus promoting idealistic worship of the role of the rational discourse. Key words: Communicative Action, Rational Discourse, Communicative Mind, Communicative Community, Post-Marxism The theory of communicative action belongs to the set of modern post-Marxist theories. Its author is Jurgen Habermas (1929-), the German philosopher and sociologist who pertains to the second generation of the Frankfurt philosophical circle. -

Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan Devore

“The Labors of our Occupation”: Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan DeVore Megan DeVore is Associate Professor of Church History and Early Christian Studies in the Department of Theology, School of Undergraduate Studies at Colorado Christian University, Lakewood, Colorado. She earned her PhD specializing in Early Christianity from the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in the United Kingdom. Dr. DeVore is a member of the North American Patristic Society, the American Society of Church History, the Society of Biblical Literature, the Evangelical Theological Society, and the American Classical League. Around the year 401, a curious incident transpired near Roman Carthage. A cluster of nomadic long-haired monks had recently wandered into the area, causing a stir among locals. These monks took the gospel quite seriously; that is, they lived very literally one part of a gospel, “Consider the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor reap, nor gather into barns … Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they labor not” (Matt 6:26-29). They were apparently not only shunning all physical labor on behalf of medita- tive prayer, but they were also (at least according to Augustine’s depiction of the situation) imposing such unemployment upon others, namely local barbers. In response, Augustine penned a unique pamphlet. It takes the form of a retort, but as it unfolds, a commentary on the dignity and duty of work emerges—manual labor, in itself significant, as well as “the labors of our occupation” (labores occupationem nostrarum) and “labor according to our rank and duty” (pro nostro gradu et officio laborantibus, De Op.