Reintegrating Theories, Methods, and Historical Analysis in Teaching Sociology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acknowl Edgments

Acknowl edgments This book has benefited enormously from the support of numerous friends, colleagues, and institutions. We thank the Wenner-Gr en Foundation and the National Science Foundation for the generous grants that made this research pos si ble. We are also grateful to our respective in- stitutions, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Stanford University, for the faculty research funds that supported the preliminary research for this proj ect. Fellowships from the Stanford Humanities Center and the Mi- chelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research provided crucial support for Sylvia Yanagisako’s writing. The Shanghai Social Sciences Institute was an ideal host for our research in Shanghai. We especially thank Li Li for help with introductions. The invitation to pres ent the Lewis Henry Morgan Distinguished Lecture of 2010 gave us the opportunity to pres ent an early analy sis and framing of our ethnographic material. We thank Robert Foster and Thomas Gibson and their colleagues in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Rochester for extending this invitation to us. The astute commentaries on our Mor- gan Lecture by Robert Foster, David Horn, Rebecca Karl, Eleana Kim, John Osburg, and Andrea Muehlebach wer e invaluable in the development and writing of this book. Donald Donham, Leiba Faier, James Ferguson, Gillian Hart, Gail Hershat- ter, George Marcus, Megan Moodie, Donald Moore, Anna Tsing, and Mei Zhan read vari ous chapters and gave the kind of honest feedback that makes all the difference. Conversations with Gopal Balakrishnan, Laura Bear, Chris- topher Connery, Karen Ho, Dai Jinhua, Keir Martin, and Massimilliano Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/chapter-pdf/678904/9781478002178-xi.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Mollona invigorated our analyses of transnational capitalism. -

National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2009

2009 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Advancing Excellence in Health Care • www.ahrq.gov 2009 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 AHRQ Publication No. 10-0004 March 2010 www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr09.htm Acknowledgments The NHDR is the product of collaboration among agencies across the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Many individuals guided and contributed to this report. Without their magnanimous support, this report would not have been possible. Specifically, we thank: Primary AHRQ Staff: Carolyn Clancy, William Munier, Katherine Crosson, Ernest Moy, and Karen Ho. HHS Interagency Workgroup for the NHQR/NHDR: Girma Alemu (HRSA), Roxanne Andrews (AHRQ), Hakan Aykan (ASPE), Magda Barini-Garcia (HRSA), Douglas Boenning (HHS-ASPE), Miriam Campbell (CMS), Cecelia Casale (AHRQ- OEREP), Fran Chevarley (AHRQ-CFACT), Rachel Clement (HRSA), Daniel Crespin (AHRQ), Agnes Davidson (OPHS), Denise Dougherty (AHRQ-OEREP), Len Epstein (HRSA), Erin Grace (AHRQ), Tanya Grandison (HRSA), Miryam Gerdine (OPHS-OMH), Darryl Gray (AHRQ-CQuIPS), Saadia Greenberg (AoA), Kirk Greenway (IHS), Lynne Harlan (NIH/NCI), Karen Ho (AHRQ-CQuIPS), Edwin Huff (CMS), Deloris Hunter (NIH/NCMHD), Memuna Ifedirah (CMS), Kenneth Johnson (OCR), Jackie Shakeh Kaftarian (AHRQ-OEREP), Richard Klein (CDC-NCHS), Deborah Krauss (CMS/OA/OCSQ), Shari Ling (CMS), Leopold Luberecki (ASPE), Diane Makuc (CDC-NCHS), Ernest Moy (AHRQ-CQuIPS), Ryan Mutter (AHRQ- CDOM), Karen Oliver (NIH-NIMH), Tanya Pagan-Raggio (HRSA/CQ), Judith Peres (ASPE), Susan Polniaszek (ASPE), Barry Portnoy (NIH-ODP), Georgetta Robinson (CMS), William Rodriguez (FDA), Rochelle Rollins (OMH), Susan Rossi (NIH), Asel Ryskulova (CDC-NCHS), Judy Sangl (AHRQ-CQuIPS), Adelle Simmons (HHS-ASPE), Alan E. -

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Making Markets and Constructing Crises: a Review of Ho's Liquidated

The Qualitative Report Volume 17 Number 15 Book Review 3 4-9-2012 Making Markets and Constructing Crises: A Review of Ho’s Liquidated Alexandra B. Cox University of Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Social Statistics Commons Recommended APA Citation Cox, A. B. (2012). Making Markets and Constructing Crises: A Review of Ho’s Liquidated. The Qualitative Report, 17(15), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1786 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Making Markets and Constructing Crises: A Review of Ho’s Liquidated Abstract This book review is a beginning academic researcher’s interpretation of the robust methods and rich data Ho presents in her study of investment banking culture and the market in Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street (2009). A unique contribution of the text is Ho’s combining of ethnographic methods in order to practice polymorphous engagement in her study. A weakness of the text is Ho’s lacking autoethnographic analysis of her experience as an Asian American woman on Wall Street. The book will be helpful for a scholarly audience interested in studying rigorous ethnographic methodologies and exploring the culture of Wall Street. Keywords Ethnography, Polymorphous Engagement, Pre-fieldwork, allW Street Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. -

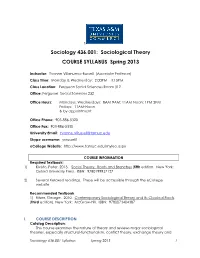

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

Melissa S. Fisher WALL STREET WOMEN

Wall Street Women Melissa S. Fisher WALL STREET WOMEN Melissa S. Fisher Duke University Press Durham and London 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. For my Bubbe, Rebecca Saidikoff Oshiver, and in the memory of my grandmother Esther Oshiver Fisher and my grandfather Mitchell Salem Fisher CONTENTS acknowledgments ix introduction Wall Street Women 1 1. Beginnings 27 2. Careers, Networks, and Mentors 66 3. Gendered Discourses of Finance 95 4. Women’s Politics and State-Market Feminism 120 5. Life after Wall Street 136 6. Market Feminism, Feminizing Markets, and the Financial Crisis 155 notes 175 bibliography 201 index 217 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A commitment to gender equality first brought about this book’s journey. My interest in understanding the transformations in women’s experiences in male-dominated professions began when I was a child in the seventies, listening to my grandmother tell me stories about her own experiences as one of the only women at the University of Penn- sylvania Law School in the twenties. I also remember hearing my mother, as I grew up, speaking about women’s rights, as well as visiting my father and grandfather at their law office in midtown Manhattan: there, while still in elementary school, I spoke to the sole female lawyer in the firm about her career. My interests in women and gender studies only grew during my time as an undergraduate at Barnard College. -

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise Max Coleman Oberlin College Sociology Department Senior Honors Thesis April 2014 Table of Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 I. What Is Anomie? Introduction 6 Anomie in The Division of Labor 9 Anomie in Suicide 13 Debate: The Causes of Desire 23 A Sidenote on Dualism and Neuroplasticity 27 Merton vs. Durkheim 29 Critiques of Anomie Theory 33 Functionalist? 34 Totalitarian? 38 Subjective? 44 Teleological? 50 Positivist? 54 Inconsistent? 59 Methodologically Unsound? 61 Sexist? 68 Overly Biological? 71 Identical to Egoism? 73 In Conclusion 78 The Decline of Anomie Theory 79 II. Why Anomie Still Matters The Anomic Nation 90 Anomie in American History 90 Anomie in Contemporary American Society 102 Mental Health 120 Anxiety 126 Conclusions 129 Soldier Suicide 131 School Shootings 135 III. Looking Forward: The Solution to Anomie 142 Sociology as a Guiding Force 142 Gemeinschaft Within Gesellschaft 145 The Religion of Humanity 151 Final Thoughts 155 Bibliography 158 2 To those who suffer in silence from the pain they cannot reveal. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Professor Vejlko Vujačić for his unwavering support, and for sharing with me his incomparable sociological imagination. If I succeed as a professor of sociology, it will be because of him. I am also deeply indebted to Émile Durkheim, who first exposed the anomic crisis, and without whom no one would be writing a sociology thesis. 3 Abstract: The term anomie has declined in the sociology literature. Apart from brief mentions, it has not featured in the American Sociological Review for sixteen years. Moreover, the term has narrowed and is now used almost exclusively to discuss deviance. -

Sociology of Finance

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY European Electronic Newsletter Vol. 2, No. 2 (January 2001) XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Editor: Johan Heilbron Managing Editor: Arnold Wilts Distributor: SISWO/Institute for the Social Sciences Amsterdam TABLE OF CONTENTS Articles A Dutch treat: Economic sociology in the Netherlands by Ton Korver 2 Sociology of Finance – Old and new perspectives by Reinhard Blomert 9 Sense and sensibility: Or, how should Social Studies of Finance behave, A Manifesto by Alex Preda 15 Book Reviews Ludovic Frobert, Le Travail de François Simiand (1873-1935), by Frédéric Lebaron 19 Ruud Stokvis, Concurrentie en Beschaving, Ondernemingen en het Commercieel Beschavingsproces by Mario Rutten 21 Herbert Kalthoff et al., Facts and Figures: Economic Representations and Practice by Johan Heilbron 23 Conference Reports The Cultures of Financial Markets (Bielefeld, Nov. 2000) by Alex Preda 25 Auspicious Beginnings for the Anthropology of Finance (San Francisco, Nov. 2000) by Monica Lindh de Montoya 27 Social Capital: Theories and Methods (Trento, Oct. 2000) by Giangiacomo Bravo 30 PhD’s in Progress 32 Just Published 36 Announcements 37 ***** Back issues of this newsletter are available at http://www.siswo.uva.nl/ES For more information, comments or contributions please contact the Managing Editor at: [email protected] 1 A DUTCH TREAT: ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY IN THE NETHERLANDS By Ton Korver Dept. PEW, Tilburg University, PO Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg The Netherlands [email protected] 1. The demise of sociology a. failed professionalization Sociology in the Netherlands is a marginal enterprise in the academic marketplace. Peaking in the sixties and early seventies, by the end of the 20th century, sociology (and with it: political science) has been reduced to a dismally small scale.