Discussion of Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Movement and Collective Action Area Exam

Social Movement and Collective Action Area Exam Updated August 2020 Format, Expectations, and Scope Students taking the social movements and collective action area exam are expected to be familiar with the development of the field, the dominant theoretical traditions, the major substantive questions and debates, and the various methodological approaches employed. At the same time, we want to make explicit that the canon upon which this field is based is largely dominated by white cis-men and by Americanist and Eurocentric perspectives. This is a problem not just in the social movements and collective action field, but across sociology more broadly. While the reading list provided here intends to be as inclusive as possible, we face the dilemma of ensuring that students are conversant in foundational works while keeping the list concise. This necessarily limits the inclusivity of the list. We therefore acknowledge this disparity and welcome students to challenge these inequities. Students may do so by providing critiques of canonical texts’ standpoints and biases; by suggesting how inclusivity, marginalized scholars, and under-examined cases can advance the field theoretically, empirically, and methodologically; and by bringing in under-utilized texts. At the same time, any challenge to the canon is going to be ineffective without deep familiarity with the canon. This reading list will therefore provide the foundation for innovation. On the day of the exam, students will answer three out of six questions (students will skip the three questions they least want to answer). Students can bring the reading list (below) and two single-spaced pages of notes to the exam (font must be at least 11 point). -

Module 6 Social Protests and Social Movements Lecture 31 Theories of Social Movements

NPTEL – Humanities and Social Sciences – Introduction to Sociology Module 6 Social Protests and Social Movements Lecture 31 Theories of Social Movements A variety of theories have attempted to explain how social movements develop. Some of the better-known approaches are outlined below. Deprivation Theory Deprivation theory argues that social movements have their foundations among people who feel deprived of some good(s) or resource(s). According to this approach, individuals who are lacking some good, service, or comfort are more likely to organize a social movement to improve (or defend) their conditions (Morrison 1978). There are two significant problems with this theory. First, since most people feel deprived at one level or another almost all the time, the theory has a hard time explaining why the groups that form social movements do when other people are also deprived. Second, the reasoning behind this theory is circular – often the only evidence for deprivation is the social movement. If deprivation is claimed to be the cause but the only evidence for such is the movement, the reasoning is circular (Jenkins and Perrow 1977). Mass-Society Theory Mass-Society theory argues that social movements are made up of individuals in large societies who feel insignificant or socially detached. Social movements, according to this theory, provide a sense of empowerment and belonging that the movement members would otherwise not have (Kornhauser 1959). In fact, the key to joining the movement was having a friend or associate who was a member of -

Fascism 10 (2021) 202-227

Fascism 10 (2021) 202-227 Fascism and (Transnational) Social Movements: A Reflection on Concepts and Theory in Comparative Fascist Studies Tomislav Dulić Hugo Valentin Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden [email protected] Abstract Scholars have recently begun advocating for the application of social movement theory in the analysis of the rise and development of fascist political entities. While representing a welcome effort to increase the theoretical depth in the analysis of fascism, the approach remains hampered by conceptual deficiencies. The author addresses some of these by the help of a critical discussion that problematises the often incoherent ways in which the concept of ‘movement’ is used when describing fascist political activity both within and across national borders. The analysis then turns to the application of social movement theory to the historical example of the Ustašas. While recent research on social movements has begun to explore the role and character of transnationalism, this case study analysis suggests that the lack of supra-national organisations during the period of ‘classic’ fascism prevented the emergence of a ‘transnational public space’ where fascist movements could have participated. The conclusion is that rather than acting and organising on a ‘transnational’ level, fascist entities appear to have limited themselves to state-based international ‘knowledge-transfer’ of a traditional type. Keywords Croatia – fascism – social movements – transnationalism – Ustaša (uhro) In a recent article, Kevin Passmore argued for the need to use social move- ment theory in the analysis of fascism. Departing from a critique of ‘generic © Tomislav DuliĆ, 2021 | doi:10.1163/22116257-10010008 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailingDownloaded cc-by license from Brill.com06/24/2021at the time of 02:39:11PM publication. -

25+ YEARS SINCE "FRAME ALIGNMENT”* David A. Snow, Robe

THE EMERGENCE, DEVELOPMENT, AND FUTURE OF THE FRAMING PERSPECTIVE: 25+ YEARS SINCE "FRAME ALIGNMENT”* David A. Snow, Robert D. Benford, Holly J. McCammon, Lyndi Hewitt, and Scott Fitzgerald† It has been more than twenty-five years since publication of David Snow, Burke Rochford, Steven Worden, and Robert Benford’s article, “Frame Alignment Processes, Micro- mobilization, and Movement Participation” in the American Sociological Review (1986). Here we consider the conceptual and empirical origins of the framing perspective, how its introduction fundamentally altered and continues to influence the study of social movements, and where scholarly research on social movement framing is still needed. Over twenty-five years ago, David Snow, Burke Rochford, Steven Worden, and Robert Benford published an article in the American Sociological Review (1986) titled, “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” In the years since, this foundational work has altered the direction of social movement research in profound ways. In the following pages, David Snow and Rob Benford describe the inception, emer- gence, and development of the framing perspective. Holly McCammon charts recent direc- tions in framing scholarship, and Lyndi Hewitt and Scott Fitzgerald point to a number of areas in which framing research continues to need the close attention of scholars. We see our collective reflection on the trajectory of this major theoretical paradigm as instructive in a number of ways: (1) it reveals the backstage dynamics entailed in the for- mation of significant intellectual ideas, reminding us that genuine curiosity about human behavior often informs powerful research ideas; (2) it proffers an explanation of the rise and wide reception of the framing perspective; (3) it provides an extensive overview of current empirical research on framing; and (4) it offers us an opportunity to take stock of the framing perspective—to articulate twenty-five years after this seminal work what we do and still do not know. -

Applying Social Movement Theory to Nonhuman Rights Mobilization and the Importance of Faction Hierarchies

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 10-2012 Applying Social Movement Theory to Nonhuman Rights Mobilization and the Importance of Faction Hierarchies Corey Lee Wrenn Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/anirmov Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Wrenn, C. L., & Collins, F. (2012). Applying Social Movement Theory to Nonhuman Rights Mobilization and the Importance of Faction Hierarchies. Peace Studies Journal, 5(3), 27-44. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 5, Issue 3 October 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________ Applying Social Movement Theory to Nonhuman Rights Mobilization and the Importance of Faction Hierarchies Author: Corey Lee Wrenn, M.S. Adjunct Professor, Liberal Arts Department Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design 1600 Pierce St. Denver, CO 80214 Instructor, Sociology Department Colorado State University B271 Clark Building Ft. Collins, CO 80523 Email: [email protected] APPLYING SOCIAL MOVEMENT THEORY TO NONHUMAN RIGHTS MOBILIZATION AND THE IMPORTANCE OF FACTION HIERARCHIES Abstract This paper offers an exploratory analysis of social movement theory as it relates to the nonhuman animal rights movement. Individual participant motivations and experiences, movement resource mobilization, and movement relationships with the public, the political environment, historical context, countermovements, and the media are discussed. In particular, the hierarchical relationships between factions are highlighted as an important area for further research in regards to social movement success. -

Socg222 · Social Movement Theory and Social Movement Research

SOCG222 · SOCIAL MOVEMENT THEORY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENT RESEARCH Winter 2012 · Mondays · 2-5 PM · SSB 414 Professor Isaac Martin · [email protected] · SSB 469 Graduate office hours by appointment “Sociology is not a science; even if it were, there are particular reasons why the study of revolution would not admit of scientific treatment.... It seems that the best way to prove that something does not admit of a particular treatment is honestly and forthrightly to make the attempt, and to persevere until it no longer works.” -- Gustav Landauer, Revolution (1907) Why and how do social movements emerge? When and how should we expect them to transform society? These questions have been central preoccupations of sociology since the beginning. Indeed, answering questions like these was arguably the very raison d'etre of sociology. Lorenz von Stein, who coined the term “social movement” in 1850, used it to refer both to the struggle of French workers for social equality, and to the dawning awareness that “society” was a thing distinct from the state. Although sociologists have been asking questions about social movements for more than a century, we have not yet pinned down the answers. Perhaps a social movement is, as Gustav Landauer said of revolution, a particularly elusive phenomenon. Consider one common definition: a social movement is a sustained, collective, and extra-institutional challenge to authority. How are we to study something that meets this definition? Because a movement is sustained and collective, any individual fieldworker will usually find it difficult to observe more than a small part of the action directly. -

Collective Behavior and Social Movements Preliminary Examination Reading List Last Edited: June 2012

Collective Behavior and Social Movements Preliminary Examination Reading List Last Edited: June 2012 Introduction and Overview Note: read as many of the following as necessary in this section to familiarize yourself with the major concepts, definitions, debates, developments, issues, methods, theoretical paradigms, etc. in the field. If in doubt, read all of them. It is highly recommended that you read them in chronological order (oldest first, newest last) so you can understand the growth of the field. However, for convenience in retrieving citations, they are listed alphabetically within each section. Klandermans, Bert and Suzanne Staggenborg. 2002. Methods of Social Movement Research. MN: University of Minnesota Press. Snow, David A., Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2004. “Mapping the Terrain.” Pp. 3-16 in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, and H. Kriesi. Oxford: Blackwell. Snow, David A. 2004. “Social Movements as Challenges to Authority: Resistance to an Emerging Conceptual Hegemony.” Research in Social Movements, Conflicts, and Change 25:3-25. Tarrow, Sidney. 1998. Power in Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Ch. 1 & 2 (pages 1-25), “Introduction” & “Contentious Politics and Social Movements.” Tilly, Charles. 2006. Regimes and Repertoires. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Ch. 8 (pages 179-208), “Social Movement.” Collective Behaviorist Tradition: Classical Statements, Applications, Elaborations, and Criticisms Bergesen, Albert, and Max Herman. 1998. “Immigration, Race, and Riot: The 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.” American Sociological Review, 633: 39-54. Buechler, Steven M. 2004. “The Strange Career of Strain and Breakdown Theories of Collective Action.” Pp. 47-66 in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D. -

Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory: Conditions, Mechanisms, and Effects

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 10 Number 4 Article 3 Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory: Conditions, Mechanisms, and Effects D.W. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 42-63 Recommended Citation Lee, D.W.. "Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory: Conditions, Mechanisms, and Effects." Journal of Strategic Security 10, no. 4 (2017) : 42-63. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.10.4.1647 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol10/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory: Conditions, Mechanisms, and Effects This article is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol10/ iss4/3 Lee: Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory Introduction Contemporary conflicts have become more transnational, protracted, irregular, and resistance-centric.1 They can be best described as protracted internal conflicts with multiple state actors and non-state actors intervening much like the multidimensional hybrid operational environment discussed in Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) 2022.2 This article aims to explain how to harness the emerging strategic utility of non-state actors by utilizing well-established bodies of knowledge on resistance dynamics. This objective is based upon the observation that an increasing number of external state actors overtly or covertly intervene in intrastate conflicts by exploiting the environment’s resistance potential in order to increase their respective strategic influence.3 Similarly, both internal and external non-state actors take advantage of interstate conflicts or political instability stemming from failing states. -

The Impact of Social Media on Social Movements: the New Opportunity and Mobilizing Structure

The Impact of Social Media on Social Movements: The New Opportunity and Mobilizing Structure Amandha Rohr Lopes Creighton University 4/1/2014 The Impact of Social Media on Social Movements: The New Opportunity and Mobilizing Structure Amandha Rohr Lopes This paper seeks to explain and test the formation process of social movements by addressing two overarching interrelated factors: opportunity structures and mobilizing structures. I hypothesize that social movements are caused by opportunity structures such as economic, institutional, and social contexts of a country conditioned by its access to social media. Social movements are not created by a single variable but rather by a set of variables that create an interaction effect. Discovering ways to mass organize is as essential for the occurrence of social movements as the grievances that make people want to organize in the first place. The introduction of social media into the discussion is thought to have completely changed the way people are able to organize. In order to test my hypothesis, I use data from a number of different sources for all countries in 2008 - 2012. Research Question Scholars have long considered under what conditions social movements are most likely to emerge. The communication revolution brought about from the rapid emergence of social media has led scholars to shift the direction of such questions to the impact of social media in social movements. Social movements have been implemented in many different forms and on different levels in order to transform societies. New studies are now looking at social media as a tool in shaping social movements’ agendas and aiding collective action both online and offline at the local or global level. -

Social Movement Theory and Far Right Organizations Frank Tridico Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2011 Social movement theory and far right organizations Frank Tridico Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Tridico, Frank, "Social movement theory and far right organizations" (2011). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 481. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. SOCIAL MOVEMENT THEORY AND FAR RIGHT ORGANIZATIONS by FRANK TRIDICO DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2012 MAJOR: SOCIOLOGY Approved by: ___________________________________ Advisor Date ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ©COPYRIGHT BY FRANK TRIDICO 2012 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents Orlando and Immacolata Tridico, who sacrificed all their lives for their family, and taught the most important principles to live by through their example. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am most appreciative to my wife Rita, who has been supportive throughout this process. She has listened, helped offer different perspectives, and encouraged objectivity. She has been instrumental in helping me achieve my goals and to become a better person. I am blessed to have my sons James and Daniel, who have given me a greater understanding of the miracle of life and the gift of family. I am thankful to Dr. Leon H. -

Frames and Ideologies in Social Movement Research

What a Good Idea! Frames and Ideologies in Social Movement Research Pamela E. Oliver University of Wisconsin [email protected] Hank Johnston San Diego State University [email protected] What a Good Idea! Frames and Ideologies in Social Movement Research Abstract Frame theory is often credited with “bringing ideas back in” to the study of social movements, but frames are not the only useful ideational concepts. In particular, the older, more politicized concept of ideology needs to be used in its own right and not recast as a frame. Frame theory is rooted in linguistic studies of interaction, and points to the way shared assumptions and meanings shape the interpretation of any particular event. Ideology theory is rooted in politics and the study of politics, and points to coherent systems of ideas which provide theories of society coupled with value commitments and normative implications for promoting or resisting social change. Ideologies can function as frames, but there is more to ideology than framing. Frame theory offers a relatively shallow conception of the transmission of political ideas as marketing and resonating, while a recognition of the complexity and depth of ideology points to the social construction processes of thinking, reasoning, educating, and socializing. Social movements can only be understood by genuinely linking social psychological and political sociology concepts and traditions, not by trying to rename one group in the language of the other. What a Good Idea! Frames and Ideologies in Social Movement Research The study of social movements has always had one foot in social psychology and the other in political sociology, although at times these two sides have seemed to be at war with each other. -

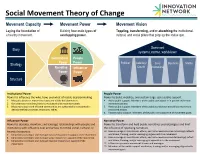

Social Movement Theory of Change

Social Movement Theory of Change Movement Capacity Movement Power Movement Vision Laying the foundation of Building four main types of Toppling, transforming, and/or absorbing the institutional, a healthy movement. overlapping power. cultural, and social pillars that prop up the status quo. Dominant Story systems, norms, worldviews Institutional People Power Power Strategy Political Judiciary/ Civic Business Media Narrative Influencer Courts Institutions Power Power Structure Institutional Power People Power Power to influence the who, how, and what of visible decisionmaking. Power to build, mobilize, and sustain large-scale public support. 1. Mutuality between movement actors and visible decisionmakers. 4. Active public support: Members of the public participate in in-person and virtual 2. Decisionmaker decisions/actions are aligned with movement goals. movement actions. 3. Movement actors and affected communities are authentically represented in 5. Active public support: Members of the public contribute financially to movement decisionmaking processes, structures, tables. actors and actions. 6. Passive public support: Members of the public are supportive of movement goals. Influencer Power Narrative Power Power to develop, maintain, and leverage relationships with people and Power to transform and hold public narratives and ideologies and limit institutions with influence over and access to critical social, cultural, or the influence of opposing narratives. financial resources. 10. Issue coverage in mainstream, ethnic, and niche media sources increasingly reflects 7. Influencers contribute and leverage cultural resources in support of the movement. worldview, framing, and/or messaging aligned with the movement. 8. Influencers contribute and leverage social resources in support of the movement. 11. Issue coverage in mainstream, ethnic, and niche media sources decreasingly reflect 9.