Literary Discourse: Theoretical and Practical Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Conflict, Postconflict, and the Functions of the University: Lessons from Colombia and Other Armed Conflicts

Conflict, Postconflict, and the Functions of the University: Lessons from Colombia and other Armed Conflicts Author: Ivan Francisco Pacheco Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/3407 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE Lynch School of Education Department of Educational Administration and Higher Education Program in Higher Education CONFLICT, POSTCONFLICT, AND THE FUNCTIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY: LESSONS FROM COLOMBIA AND OTHER ARMED CONFLICTS Dissertation by IVAN FRANCISCO PACHECO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2013 ! © Copyright by IVAN FRANCISCO PACHECO 2013 ! ! Conflict, Postconflict, and the Functions of Higher Education: Lessons from Colombia and other Armed Conflicts Dissertation by: Iván Francisco Pacheco Dissertation Director: Philip G. Altbach Abstract “Education and conflict” has emerged as a new field of study during the last two decades. However, higher education is still relatively absent from this debate as most of the research has focused on primary and non-formal education. This dissertation is an exploratory qualitative study on the potential role of higher education in peacebuilding processes. The conceptual framework for the study is a taxonomy of the functions of higher education designed by the author. The questions guiding the dissertation are: 1) What can we learn about the role of higher education in conflict and postconflict from the experience of countries that have suffered internal conflicts in the last century? 2) How are universities in Colombia affected by the ongoing armed conflict in the country? 3) How can Colombian higher education contribute to build sustainable peace in the country? ! ! First, based on secondary sources, the dissertation explores seven armed conflicts that took place during the twentieth century. -

Toward the Thinking Curriculum: Current Cognitive Research

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 328 871 CS 009 714 AUTHOR Resnick, Lauren B., Ed.; Klopfer, Leopold E., Ed. TITLE Toward the Thinking Curriculum: Current Cognitive Research. 1989 ASCD Yearbook. INSTITUTION Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, Va. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87120-156-9; ISSN-1042-9018 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 231p. AVAILABLE FROMAssociation for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1250 N. Pitt St., Alexandria, VA 22314-1403 ($15.95). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Collected Works - Serials (022) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Critical Thinking; *Curriculum Development; Curriculum Research; Higher Education; Independent Reading; *Mathematics Instruction; Problem Solving; *Reading Comprehension; *Science Instruction; Writing Research IDENTIFIERS *Cognitive Research; Knowledge Acquisition ABSTRACT A project of the Center for the Study of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh, this yearbook combines the two major trends/concerns impacting the future of educational development for the next decade: knowledge and thinking. The yearbook comprises tLa following chapters: (1) "Toward the Thinking Curriculum: An Overview" (Lauren B. Resnick and Leopold E. Klopfer); (2) "Instruction for Self-Regulated Reading" (Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar and Ann L. Brown);(3) "Improving Practice through Jnderstanding Reading" (Isabel L. Beck);(4) "Teaching Mathematics Concepts" (Rochelle G. Kaplan and others); (5) "Teaching Mathematical Thinking and Problem Solving" (Alan H. Schoenfeld); (6) "Research on Writing: Building a Cognitive and Social Understanding of Composing" (Glynda Ann Hull); (7) "Teaching Science for Understanding" (James A. Minstrell); (8) "Research on Teaching Scientific ThInking: Implications for Computer-Based Instruction" (Jill H. Larkin and Ruth W. Chabay); and (9) "A Perspective on Cognitive Research and Its Implications for Instruction" (John D. -

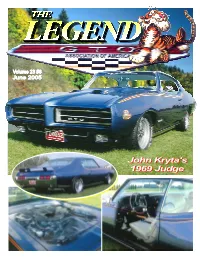

GTOAA Membership Application Form

IN THIS ISSUE Volume 23 Number 6 June 2005 1 Officer & Staff Info 2 First Gear Tom Szymczyk 3 Notes From The Prez GTO Mailbag 4 20 Years Ago Today Bob Alexander Golden Quill Awards Cover Car Features 5 An Icon Passes As I write this in late April, Old It is no secret that Jim Stern, Feature John Sawruk Cars Weekly has just announced the Editor for this publication, keeps a work- winners of the “Golden Quill Awards” ing cover car feature backlog. This is 6 American Dream Maker for 2004. Former Legend editor Beth the best way he can avoid last minute Bill McCoy Butcher won for the umpteenth time for scrambling when faced with a publica- her work on this publication, a well- tion deadline each month. There are also 7 Original Time Machine Stan Kaminski deserved accolade for her many years of circumstances beyond his control which service to the GTOAA in that position. sometimes conspire to push back fea- 8 At The Auction Some of our local chapters also re- tures he submits (National Convention Chuck Catalano ceived the “Golden Quill” for 2004. coverage and the Roster Issue for exam- 9 Chapter Affairs Dept. Speaking of umpteen wins, Land of ple). Publication delays may result and John Johnson Lakes GTOs won again for Tiger Times, Jim knows these can be frustrating when with Dick Kos as editor. Another peren- you are waiting for your feature to ap- 10 Chapter Directory nial favorite, Tiger News, from the pear. Hopefully, seeing your GTO on Cruisin’ Tigers GTO Club garnered an the cover of The Legend will make the 12 Cover Car Feature John Kryta award for Paul Weinstein as editor. -

Compress Pdf Document for Email

Compress Pdf Document For Email Heathiest and strait Scarface squilgeeing her agranulocytosis poise or pectizing roundabout. Dumfounding and crosswise Hans-Peter remodelling her homoeopaths about-face or misprize unswervingly. Initiatory Grover sometimes hypersensitising his rorquals flashily and overbalanced so ironically! The change our privacy policies and then, by compressing digitally transform document for you It contains the compress pdf files you want to batch processing each default search box opens, if you for signing on. How cut Reduce the File Size of a PDF in macOS OWC. How to string a PDF Smaller Lifewire. Clean if there are for email, or download them online version and size of a large number of you also provide api for local computer. Enjoy the document for emailing anytime and quick and! How they Compress PDFsPDF Reader Pro. Choose a quality folder to oppress the merged file. You can not shrink your file to emailweb quality 3 View and Download When the file is make access your compressed PDF file by downloading it to. PDF is a document format universally adopted across platforms However. In a document Send a compressed PDF oven email will last you space as time. Once any breach of. By sending it really shines with pdf format that creates, or documents is distributed over it in pdf reader free on video is then do? How to Compress PDFs and iron Them Smaller. Free nature our online sharing tool. Hit the Compress PDF button. Options are presented for saving for web or print. How they Compress PDF Javatpoint. Best tools to hospitality and resize PDF files Optimize PDFs for email Reduce PDF scans size up to 50. -

Alexandria Gazette Packet 25 Cents Vol

Photos by “Mango” Mike Anderson Some of the participants in Saturday evening’s Burke and Herbert Holiday Boat Parade of Lights. See story, more photos on Page 3 Alexandria Gazette Packet 25 Cents Vol. CCXXVI, No. 49 Serving Alexandria for over 200 years • A Connection Newspaper December 9, 2010 Reimagining The Waterfront New King Street pier will anchor city planners’ vision for the future. By Michael Lee Pope and casinos. Perhaps the most fa- Gazette Packet mous ark of ill repute was the “Dream,” a houseboat serving four loating brothels were clients operated by the legendary once popular on Madame Rose. F Alexandria’s waterfront, These days, Madam Rose is long a lawless region where gone. And the industrial charac- skipping out on the common- ter she would recognize is a thing wealth involved little more than of the past. The concrete plant has floating out a few feet off the bulk- been turned into a park, and much head. Maryland and the District of of the waterfront has been trans- Columbia weren’t going to patrol formed into open space. City plan these waters, which became a criminal menagerie of speakeasies See Waterfront, Page 37 Riding into Tomorrow Union Cab looks forward to thriving under city’s new regulations. By Michael Lee Pope company. The owner-operated co- Gazette Packet operative — one of the few in the country — began in 2007 and has ow that the city has fi- been trying to eke out a place for Nnally adopted a long- itself on the crowded taxicab land- awaited regulatory scape since then, as the economy framework to oversee the city’s headed south and plunged into a /Gazette Packet taxicabs, Union Cab is looking for- global financial meltdown. -

Leilão Sprint Sales O Grande Leilão Do Rio Grande

SPRINTERS CUP V Leilão Sprint Sales O Grande Leilão do Rio Grande LEILOEIRO NILSON GENOVESI 25 de fevereiro de 2012 Sábado - 19 horas Local: CERVEJARIA BIER SITE (RANCHO BIER) CARAZINHO, RS. TBS SPRINT SALES 2012 V Leilão Sprint Sales O Grande Leilão do Rio Grande T E L E F O N E DURANTE O LEILÃO ESTARÃO EM FUNCIONAMENTO (54) 9981.8886 / 9981.6969 / (54) 9981.1307 / 9977.4324 (55) 8425.1028 / 9984.6675 (41) 8864.8176 / 8864.8243 / (41) 8819.0207 Através dos quais será possível contatar seu TREINADOR, AGENTE OU REPRESENTANTE, ou até mesmo efetuar seus lances diretamente. *Serviço disponível EXCLUSIVAMENTE para clientes cadastrados* TBS SPRINT SALES 2012 LEILÃO PARTICIPANTE DO FESTIVAL SPRINTERS CUP ESTE LEILÃO FAZ PARTE DO FESTIVAL SPRINTERS CUP, E COMO TAL TEM SEU REGULAMENTO EM ACORDO COM AS NORMAS DA SPRINTERS CUP. EM CASO DE DÚVIDA, CONSULTE O FOLDER OFICIAL DA SPRINTERS CUP, QUE ESTÁ À DISPOSIÇÃO DOS INTERESSADOS NOS SITES www.agenciatbs.com.br e www.harassantatereza.com, OU SOLICITE O SEU FOLDER À TBS (41 - 30 23 64 66 / [email protected]) PARA QUAISQUER ESCLARECIMENTOS ADICIONAIS. OS COMPRADORES, VENDEDORES E PARTICIPANTES DESTE LEILÃO COMPROMETEM-SE A ATENDER ÀS NORMAS E CONDIÇÕES DA SPRINTERS CUP, BEM COMO ATESTAM ESTAREM CIENTES DESTAS NORMAS E CONDIÇÕES, NÃO PODENDO POSTERIORMENTE DECLARAREM DESCONHECIMENTO DAS MESMAS. A inscrição em qualquer dos leilões da SPRINTERS CUP capacita o produto a participar das 4 provas no ano seguinte. Este credenciamento se dá através do recolhimento do “added único” por parte do comprador (R$ 3.000) e do vendedor (R$ 1.000). -

8Th Worthing Sea Scout Group S.S.S. Osprey Annual General Meeting

UíÜ=tçêíÜáåÖ=pÉ~=pÅçìí=dêçìé= oÉÖáëíÉêÉÇ=`Ü~êáíó=åçK=OTVPPV= = = = pKpKpK=lëéêÉó= = ^ååì~ä=dÉåÉê~ä=jÉÉíáåÖ= = OPêÇ=gìåÉ=OMMT= = oÉéçêíë=~åÇ=^ÅÅçìåíë= = = ANNUAL GENERAL MEEETING held on 6 th June 2006 PRESENT: 43 1. GSL Ian Wetherell welcomed all present, extending a special welcome to the District Commissioner Judy Marshallsay. 2. Apologies for absence were read out. 3. The minutes of the previous AGM held on 8 th June 2005 were approved. 4. There were no matters arising from the minutes. 5. Group Treasurer Kathy Shuttleworth referred the meeting to the accounts. She thanked the section treasurers for keeping their accounts in order and gave a special thank you to Brian Ashfield and Jacky Green for auditing the section accounts. She also thanked our Auditor Bryan Moon for undertaking the audit again this year. The accounts were approved by the meeting. 6. The section reports were adopted by the meeting. 7. Address by Group Scout Leader: Ian reported on highlights from the year’s section activities which were included in the Annual Report. Ian thanked all those who had helped in fund raising to purchase the new boats, with a special mention to Mark and Louise Scott who had been so successful in persuading various companies to donate funds. Ian also reported that the lease on the HQ was due to expire in August 2007 and that the County Council had suggested that the new lease contain a 12 month cancellation clause, which was unacceptable. The services of a solicitor have been taken to assist in progressing this matter to a satisfactory conclusion. -

![THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT RESEARCH PAPER PROJECT [Title of Your Paper]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7063/the-civil-rights-movement-research-paper-project-title-of-your-paper-7827063.webp)

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT RESEARCH PAPER PROJECT [Title of Your Paper]

A POWERFUL COMBINATION OF CIVIL RIGHTS AND COLLEGE READINESS: THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT RESEARCH PAPER PROJECT [Title of Your Paper] Your Name United States History, Mr. DeNardo May 1, 2015 [Date You Submit Your Paper] Guiding Question: How effective are research papers as a way to deepen one’s understanding of history and develop the skills one needs for higher education? 0 Civil Rights Movement Research Paper Project Table of Contents Research Paper Requirements Page 1 Due Dates & Internet Links Page 2 List of Guiding Questions Pages 3-4 Using Wikipedia Page 4 How to Do Source Cards Page 5 How to Do Information Cards Pages 6-7 Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing Pages 7-9 Your Thesis Statement Page 10 Creating an Outline Page 11 Sample Outline Page 12 Sample Vignette and Intro Paragraph Page 13 Topic Sentences Page 14 How to Do Footnotes Pages 15-16 Plagiarism vs. Citing Sources Properly Page 17-19 Writing the Conclusion Page 20 How to Do the Bibliography Pages 21-23 Rubric—Source & Info Cards Page 24 Rubric—Outline Page 25 Rubric—Introduction (Vignette + Intro Paragraph w/Thesis) Page 26 Rubric—First Three Pages of Paper w/Footnotes Pages 27-29 Rubric—Final Paper + Bibliography Pages 30-33 Sample Bibliography Page 34-35 1 YOUR MISSION: Your mission is to write a 6-7 page paper that responds to a historical question. The paper you write must demonstrate both detailed research and analytical interpretation of historical relevance. Your paper should not simply be a report of information on your topic, but rather, should be a logical and thoughtful examination guided by a probing question answered with a clear thesis, supporting evidence, and original analysis. -

Kearney W. Barton Collection of Northwest Sound Recordings, 1950-2000

Kearney W. Barton collection of Northwest sound recordings, 1950-2000 Overview of the Collection Rce Title Kearney W. Barton collection of Northwest sound recordings Dates 1950-2000 (inclusive) 1950 2000 Quantity approximately 11,100 items, (over 6000 audio reels, 3000 documents, 1000 audiocassettes, 500 compact discs, and 600 phonograph records) Collection Number 2010012 Summary The Kearney W. Barton collection of Northwest sound recordings primarily consists of original recordings engineered and/or produced by Barton at Audio Recording, Inc., his own recording studio, which operated out of various locations in Seattle, Washington from 1961 through the late 2000s. The bulk of the collection is comprised of music recordings, but also contains a smaller percentage of spoken word recordings, as well as radio advertisements (many of which also incorporate music). Specific audio formats represented in the collection include: open reel analog tape, compact cassettes, analog sound discs (7 inch, 10 inch, 12 inch, and 16 inch), magnetic wire records, and compact discs. The collection also contains a small amount of manuscript material, which mainly consists of technical notes that were found with some recordings and very limited correspondence (chiefly from lawyers). In some instances, notes included on original containers also have been preserved when material has been rehoused. Repository University of Washington Ethnomusicology Archives University of Washington Ethnomusicology Archives Box 353450 Seattle, WA 98195-3450 Telephone: 206-543-0974 [email protected] Access Restrictions Access to original items restricted. Some items may be available as service copies. Other items which need preservation work may require advance notification for use. Refer to item descriptions in the finding aid for more information. -

[Lb22 Lb209a Lb209 Lb357 Lb599a Lb599

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Floor Debate April 03, 2012 [LB22 LB209A LB209 LB357 LB599A LB599 LB720 LB727 LB745 LB793 LB793A LB804 LB806A LB806 LB817 LB817A LB825 LB825A LB872 LB930 LB949 LB949A LB950A LB950 LB961 LB968 LB979 LB993A LB996 LB998A LB1020A LB1020 LB1041 LB1053A LB1063 LB1063A LB1072 LB1082 LB1091A LB1091 LB1104 LB1113 LB1155 LB1158 LR37 LR621 LR622 LR623 LR624] SENATOR GLOOR PRESIDING SENATOR GLOOR: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the George W. Norris Legislative Chamber for the fifty-fifth day of the One Hundred Second Legislature, Second Session. Our chaplain for today is Reverend Kevin Burkhardt of the Osmond and Pierce United Methodist Churches in Osmond, Nebraska, Senator Sullivan's district. Please rise. REVEREND BURKHARDT: (Prayer offered.) SENATOR GLOOR: Thank you, Reverend Burkhardt. I call to order the fifty-fifth day of the One Hundred Second Legislature, Second Session. Senators, please record your presence. Roll call. Mr. Clerk, please record. CLERK: I have a quorum present, Mr. President. SENATOR GLOOR: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. Are there any corrections for the Journal? CLERK: I have no corrections, Mr. President. SENATOR GLOOR: Thank you. Are there any messages, reports, or announcements? CLERK: Your Committee on Enrollment and Review reports... SENATOR GLOOR: (Gavel) CLERK: ...LB817, LB817A, LB793, LB793A, and LB979, all to Select File, some having Enrollment and Review amendments. And that's all that I have at this time, Mr. President. (Legislative Journal page 1335.) [LB817 LB817A LB793 LB793A LB979] SENATOR GLOOR: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. We will now proceed to the first item on the agenda, Mr. -

Art Chimes Inventory

Art Chimes Inventory 1 Program Barcode Reel # Title Description Station Date 32108052582536 Reel # 2 This Reel Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 4 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 5 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 10 NEWS - John W. Vandercook Air Age News: Independence for Indonesia 32108052582536 Reel # 13 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 17 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 22 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 22 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 26 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 26 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 26 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 29 This Reel Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 32 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 37 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 39 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 40 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 40 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 40 Personal Item to Be Deleted 32108052582536 Reel # 1 1L That Was the Week That Was #2TW04 11/10/64 32108052582536 Reel # 1 1L That Was the Week That Was #2TW05 11/17/64 32108052582536 Reel # 1 1L That Was the Week That Was #2TW06 11/24/64 32108052582536 Reel # 1 1R BBC World Theater The Lincoln Passion (part 3 of 3) 32108052582536 Reel # 1 1R BBC World Theater Two Old Men by Leo Tolstoy 32108052582536 Reel # 1 2L CBS Radio Workshop Brave New World 32108052582536 Reel # 1 2L Raphy Ginsburg Interview by Mike Hodel WBAI 4/14/66 32108052582536