The Right to Cable Royalties and the Divisibility of Copyright: Understanding the Interaction Jacqueline A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

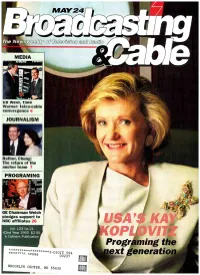

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

Statutes and Rules Affecting Local Programming on Broadcast, Cable, and Satellite Television

“Localism”: Statutes and Rules Affecting Local Programming on Broadcast, Cable, and Satellite Television -name redacted- Specialist in Telecommunications Policy January 9, 2008 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL32641 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress “Localism”: Statutes and Rules Affecting Local Programming Summary Most broadcast television stations’ viewing areas extend far beyond the borders of their city of license, and in many cases extend beyond state borders. Under existing FCC rules, which are intended to foster “localism,” the licensee’s explicit public interest obligation is limited to serving the needs and interests of viewers within the city of license. Yet, in many cases, the population residing in the city of license is only a small proportion of the total population receiving the station’s signal. Hundreds of thousands of television households in New Jersey (outside New York City and Philadelphia), Delaware (outside Philadelphia), western Connecticut (outside New York City), New Hampshire (outside Boston), Kansas (outside Kansas City, Missouri), Indiana (outside Chicago), Illinois (outside St. Louis), and Kentucky (outside Cincinnati) have little or no access to broadcast television stations with city of license in their own state. The same holds true for several rural states—including Idaho, Arkansas, and especially Wyoming, where 54.55% of television households are located in television markets outside the state. Although market forces often provide broadcasters the incentive to be responsive to their entire serving area, that is not always the case. This report provides, for each state, detailed county-by-county data on the percentage of television households located in television markets outside the state and whether there are any in-state stations serving those households. -

Is Retransmission Consent Still Needed in 2016: a Look at Regulation, Consumers, Technology and Profit

Is Retransmission Consent Still Needed in 2016: A Look at Regulation, Consumers, Technology and Profit A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Chelsea A O’Rourke in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Television Management August 2016 © Copyright 2016 Chelsea A. O’Rourke. All Rights Reserved. i Acknowledgments I would like to thank all my advisors and colleagues at Drexel University. Mary Cavallaro my advisor, Al Tedesco, Philip Salas thanks for helping to counseling me through this processes. Dave Culver, not only my boss, but my mentor and friend. In addition to so many more people at Drexel. Thanks to my family who never questioned helping in whatever ways they could. Thanks to my husband Mike, daughter Melanie and the baby growing now to add a little time pressure to complete this paper, thank you. To my Mother and Father, without your support encouragement and help, this would not have been possible. Thanks to all of my family both nuclear and married into. The people involved in the broadcast, MVPD and on-line television industry, I’m always impressed with the willingness to chat with anyone who picks up the phone. ii Table of Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. -

The Future of Municipal Regulation of Cable Television: Plugged in Or Tuned Out?, 15 Loy

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 15 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 1983 1983 The uturF e of Municipal Regulation of Cable Television: Plugged In or Tuned Out? Fredric D. Tannenbaum Assistant Attorney General of Illinois, Civil Appeals Division Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation Fredric D. Tannenbaum, The Future of Municipal Regulation of Cable Television: Plugged In or Tuned Out?, 15 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 33 (1983). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol15/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Future of Municipal Regulation of Cable Television: Plugged In or Tuned Out? FredricD. Tannenbaum* INTRODUCTION The cable television' industry is subject to a maze of concur- rent federal, state and local regulation. 2 The federal government, through the Federal Communications Commission ("FCC"),:' ac- tively regulates the cable television industry and establishes guidelines for the regulation of cable television by state and local authorities. The State of Illinois, through the Illinois Commerce Commission ("ICC"), initially asserted direct jurisdiction over cable television franchises. 4 A decision of the Illinois Supreme Court,5 however, has relegated the ICC to indirect regulation. Illinois municipalities have statutory authority to license, fran- chise and tax cable television companies. 6 However, two recent *Assistant Attorney General of Illinois, Civil Appeals Division, formerly in the Public Utilities Division; B.A. -

Toward a Freer Market in Broadcast Television

Regulation Killed the Video Star: Toward a Freer Market in Broadcast Television Ryan Radia* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 236 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 241 A. The Birth of Cable Television ............................................... 241 B. Statutory Copyright License for Broadcast Signal Retransmission ...................................................................... 244 C. Cable Act of 1992: Congress Establishes Retransmission Consent ................................................................................. 246 D. Similar Rules Govern Satellite Carriers ............................... 249 III. MVPDS AND BROADCASTERS GO HEAD-TO-HEAD IN WASHINGTON .................................................................................. 251 A. Mandatory Carriage Requirement ........................................ 252 B. Network Non-Duplication and Syndication Exclusivity Rules ................................................................... 253 C. How Broadcasters “Earn” Their Retransmission Consent Rights .................................................................................... 254 IV. GOVERNING A PRO-COMPETITIVE, PRO-CONSUMER VIDEO MARKETPLACE ................................................................................ 256 A. The Case for a Level Playing Field in Video ........................ 257 B. If Retransmission Consent Isn’t Broken, Why Fix It? .......... -

495 Senator METZENBAUM Let Me Ask You, Mr Hostetter—Your Entire

495 Senator METZENBAUM Let me ask you, Mr Hostetter—your entire statement will be included in the record as will the entire statement of each of the witnesses today How important is the availability of HBO to the success of a cable system, or Showtime' Mr HOSTETTER The availability of unique product is what has built the cable mdustry The product we are selling is a smorgas bord of channels And the fact that we have things from Black En tertainment Television to first run motion pictures, whether it be by HBO or by Showtime, it is the mix that we market and it is the uniqueness of that mix Senator METZENBAUM You stated recently that following the ac quisition of American Cablesystems, that it is inevitable that the cable TV mdustry will become more concentrated What is the rea soning behind that prediction7 Mr HOSTETTER Because as yet, even the largest of these compa nies are not large by American industrial standards And the trend towards concentration as a result of efficiency of operation, region al clustering of systems, additional revenue sources are gomg to come from more concentrated blocks of systems The fact that Bas- comb would have a different CATV company from Fostona or from Tiffin or from Finley is just illogical, and eventually those clusters are gomg to pull together for the efficiency of marketing the serv ice Senator METZENBAUM Am I correct that just as m TV stations, cable systems have a one-time major capital investment7 I know that there are supplemental But m the main, you lay down the wire and that is the -

Lessons from Broadcasting

The Impact of Advertising: Lessons from Broadcasting Christopher S. Yoo University of Pennsylvania Law School December 12, 2013 The FCC’s Longstanding Preference for Free Television and Radio Television Opposition to subscription TV (overturned by D.C. Cir.) Cable: superstations, bundling, antisiphoning, network nonduplication, syndication exclusivity, must carry Satellite distant signal importation, carry one, carry all Digital television transition via broadcasting Radio (conventional and satellite) Confounded with commitment to local December 12, 2013 Yoo - Advertising and Broadcast Television 2 Impact on Total Revenue Theoretically ambiguous Pay models reflect audiences’ preferences for programs Advertising models reflect responsiveness to advertising Empirically clear Noll, Peck & McGowan (1973): pay = 7x advertising Effect confirmed by Levin (1971); Besen & Mitchell (1974); Spence & Owen (1977); Ellickson (1979); Park (1980); Holden (1993); Hansen & Kyl (2001) December 12, 2013 Yoo - Advertising and Broadcast Television 3 Pricing vs. Voting Models Pricing: two ways to signal intensity of preferences Viewing vs. nonviewing Price (revenue not just a function of audience size) Voting: only one way to signal preferences (viewing) Revenue (primarily) a function of audience size CBS derives 1/8 the revenue per viewer as HBO Implications Program quality falls (HBO’s dominance of the Emmys) Programs with small audiences cannot survive (diversity) December 12, 2013 Yoo - Advertising and Broadcast Television 4 The Advertiser -

Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Federal Communications Commission FCC 14-29 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of the Commission’s Rules Related to ) MB Docket No. 10-71 Retransmission Consent ) REPORT AND ORDER AND FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: March 31, 2014 Released: March 31, 2014 Comment Date: (30 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) Reply Comment Date: (60 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) By the Commission: Chairman Wheeler and Commissioners Clyburn, Rosenworcel, Pai and O’Rielly issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................... 2 III. DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 A. Need for the Prohibition on Joint Negotiation................................................................................. 9 B. Elements of the Prohibition on Joint Negotiation.......................................................................... 24 C. Prohibited Practices ....................................................................................................................... 27 D. Authority to Adopt the Prohibition on Joint Negotiation -

Above-Entitled Matter Convened, Pursuant to Adjournment, in the Offices of the Copyright Royalty Tribunal, in Room 92Lg 1825

rI . r, I 821 BEFORE THE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Matter of 1990 CABLE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY DOCKET NO. CRT 92-1-90CD DISTRIBUTION PROCEEDING (This volume contains pages 821 through 949) Washington, D.C. Friday, September 17, 1993 The above-entitled matter convened, pursuant to adjournment, in the Offices of the Copyright Royalty Tribunal, in Room 92lg 1825 Connecticut Avenue, N.M., Mashingtoni D AC g at 10:00 a.m. BEFORE: CINDY DAUB Chairperson BRUCE D. GOODMAN Commissioner EDWARD J. DAMICH Commissioner LINDA R. BOCCHI General Counsel NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. (202) 2344433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 (202) 234-4433 822 APPEARANCES: PROGRAM SUPPLIERS: On behalf of MPAA: DENNIS LANE, ESQUIRE JANE SAUNDERS'SQUIRE BRIAN HOLLAND, ESQUIRE Morrison R Hecker 1150 18th street, N.TI(t. Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20036-3816 (202) 785-9100 Music Claimants: On behalf of ASCAP: I. FRED KOENIGSBERG, ESQUIRE White 6 Case 1155 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10036-2787 (212) 819-8200 BENNETT M. LINCOFF, ESQUIRE Senior Attorney, ASCAP One Lincoln Plaza New York, New York 10023 (212) 621-6270 On behalf of BMI: CHARLES T. DUNCAN, ESQUIRE MICHAEL FABER, ESQUIRE MARC A. LURIE, ESQUIRE Reid R Priest 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Market Square Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 508-4081 On behalf of SESAC: LAURIE HUGHES, ESQUIRE SESAC, Inc. 55 Music Square East Nashville, Tennessee 37203 (615) 320-0055 NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Bobby Likis Car Clinic Andcar Clinic Minute (See “Car Clinic Network”)

Behind This Section, Enjoy a Road Trip Through BobbyBobby LikisLikis CarCar ClinicClinic • Bobby Likis: The Man, The Myth, The Legend • Robert A. “Bobby” Likis: A Closer Look • Car Clinic Network & Programming Overview • Mission Statement • Sponsors, Partners & Guests • Press Releases • Car Clinic Featured In Industry Publications CAR CLINIC NETWORK • RADIO, INTERNET & TELEVISION STUDIOS 5675 NORTH DAVIS HIGHWAY, PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32503 OFFICE 850-478-3139 • FAX 850-477-0862 www.CarClinicNetwork.com Bobby Likis AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY SPOKESMAN A Brief Biographical Sketch It’s hard to believe that a successful businessman’s first intelligible phrase was “Hot car, Momma,” but it gets easier when you know the man in question is Bobby Likis. Born in Birmingham, a two year old Bobby uttered these words after due deliberation from the backseat of his daddy’s 1940 Ford Coupe during a July hot spell, and his first clear phrase seemed to prophesy his direction in life. Bobby ultimately moved to Pensacola, Florida, and in American-Graffiti style, he spent his formative years ignoring his studies and working on cars and girls, not necessarily in that order. Though intrigued greatly by the fairer sex, tinkering with automobiles became Bobby’s obsession, and the hot rod, drag racing atmosphere of the early ‘60s became Bobby’s real school. Cheeseburgers, hangin’ out, and chopped and channel flat-head ruled the day during that very brief, unique and vaguely innocent post-war/pre-war era, and Bobby was right smack in the middle of it all. Bobby built and rebuilt racecar engines with a knack and assiduous care that bordered on vengeance. -

United Video, Inc. V. FCC: Just Another Episode in Syndex Regulation

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 12 Number 1 Symposium on Independent Article 10 Productions 1-1-1992 United Video, Inc. v. FCC: Just Another Episode in Syndex Regulation Paula Brown Hayton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paula Brown Hayton, United Video, Inc. v. FCC: Just Another Episode in Syndex Regulation, 12 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 251 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol12/iss1/10 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED VIDEO, INC. v. FCC: JUST ANOTHER EPISODE IN SYNDEX REGULATION I. INTRODUCTION Recently, cable viewers have been flipping channels looking for their favorite syndicated shows and have, to their disappointment, not found them. The reason? Syndication Exclusivity Rules ("Syndex").l Syndex is a complex regulatory scheme promulgated by the Federal Communi- cation Commission ("FCC") that restricts the syndicated programming2 offered by cable stations.3 Syndex became fully effective on January 1, 1990." The new rules require cable operators who import broadcast signals to delete syndicated programs at the request of local broadcasters who have purchased the exclusive local rights of these programs.5 As a result of Syndex, some 1. 47 C.F.R. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of Applications of Tribune Media Company and MB Docket No. 17-179 Sinclair Broadcast Group for Consent to Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations COMMENTS OF THE AMERICAN TELEVISION ALLIANCE Mike Chappell Michael Nilsson THE AMERICAN Mark Davis TELEVISION ALLIANCE Jared Marx 1155 F Street, N.W. Paul Caritj Suite 950 HARRIS, WILTSHIRE & GRANNIS LLP Washington, DC 20004 1919 M Street, N.W. (202) 333-8667 The Eighth Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 730-1300 Counsel for the American Television Alliance August 7, 2017 SUMMARY The American Television Alliance writes to express its concern that Sinclair’s proposed acquisition of Tribune would give Sinclair ownership of multiple top-four affiliates in numerous markets, in violation of the Commission’s local ownership rules. Because Applicants have not requested a waiver of these rules, we expect that Sinclair will not proceed with its proposed purchase of stations in places like Seattle, St. Louis, and Oklahoma City. We agree with Applicants that the Commission cannot permit Sinclair to acquire these stations at this time. Yet Applicants also suggest that, if the Commission relaxes its local ownership rules, they “may file amendments” to their Application in response. ATVA would object to any subsequent attempts by Sinclair to own new “top-four duopolies” because of the increased pricing power such duopolies would confer, the increased programming costs they would impose on MVPDs, and the higher bills consumers would pay as a result. Three years ago, the Commission voted unanimously to prohibit a single entity from negotiating on behalf of two top-four stations in a market because such joint negotiation harms competition and gives that broadcaster pricing power in retransmission consent negotiations.