'Face to Face': the Difference Between Hindu and Christian Non-Dualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor ne should thank Gustavo Polit for going to such length to point out O various confusions, oversights, errors, incomprehensions, and biases which he finds in our note responding to his and Patrick Moore’s letters.1 While some of Polit’s remarks arise from misunderstanding, and with many of them one can agree (so comprehensive is their scope), he does identify genuine disagreement between us. As for misunderstanding: One does not overlook the origin of modernity within Christendom, though this was not because of a lack of genuine gnosis within the Church, as again, Jean Borella has amply documented (Guenonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery). The point was simply that Christianity has in fact borne the brunt of the modernist attack: and in fact, has the persistence of jnana prevented the ongoing modernization of India? Again, one does not reduce the universal metaphysical Order to the formal orders as Polit fears: this would amount to eliding the Uncreated order and the formless spiritual order of Creation! And then, it is no intention of ours to diminish the scope and authority of spiritual intellect merely by referring it to the metaphysical orientation of spiritual life as evoked by Mr. Lakhani’s editorial in Volume 30 of Sacred Web. As for agreement: when Polit says that metaphysical doctrine can vary only in ‘formulation’, while its Truth stands invariant over temporal events, this is in essence what we had argued earlier, regarding the distinction of doctrinal gnosis and the ultimate gnosis it symbolizes. When he says that he certainly does not aim to correct the dogma of the Trinity, we most 1 [Editor’s Note]: The letters of Patrick Moore and of Gustavo Polit appeared in Volume 30 of this journal, at pp. -

The Deep Horizon

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co-existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

The Milk of the Virgin: the Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri

From the World Wisdom online library: www. worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx The following essay is found in Sacred Web 20, edited by M. Ali Lakhani The Milk of the Virgin: The Prophet, the Saint and the Sage by Renaud Fabbri Prophets, saints, and sages: The prophet brings a form of faith — a religion; The saint lives it; the sage opens A luminous realm of Pure Spirit Beyond form. Prophets are also wise men, Yet about the highest Truth they speak softly; To the sage, holiness bestows light. God and our heart are united in eternity. (Frithjof Schuon)1 There have been a few controversies in the last decade about the teaching and personality of the 20th century Perennialist author and founder of the Maryamiyyah Sufi order, Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), 1 Frithjof Schuon, Songs without Names XII / XVI (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2007). also known under the name of Sheikh Isa Nur Ad-Din Ahmad. These controversies have been reflected to various degrees in articles published by traditionalist journals as well as in recent scholarly publications. In the following paper, it will be argued that Frithjof Schuon is best understood neither as the founder of a new religion (a prophet in the classical sense of the word) nor as a Muslim saint, but as a universal sage, a spokesman for the religio perennis whose connection with Islam, although providential, remains secondary in the context of his message of esoterism, universality and primordiality. Before we engage in an attempt at defining a sage, we will need to refute two types of criticisms against Schuon. -

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella

The Sense of the Supernatural Jean Borella Translated by G. John Champoux Preface Nature desires supernature Some fifty years ago Father de Lubac published Surnaturel: études historiques,1 and one of the major theological debates of the twentieth century sprang up around this book. Although almost completely ignored by the public, it occasioned radical confrontations between some of the most illustrious theologians of the Catholic Church. And rightly so, for it touches on what is essential. The learned Jesuit was not, as the modest subtitle announced, content with retracing the history of an idea, an idea as a matter of fact central to the organisation of Christian doctrine. He also went to work as a theologian to show that ecclesiastical tradition, except for the last two centuries, had never viewed the ideas of a ‘pure nature’ and a ‘pure supernature’ as two completely heteronomous realities. In particular he established that the affirmation of a natural desire for the supernatural, which is to say the vision of God, was to be found in St Thomas: ‘every intellect naturally desires the divine Substance’ (Summa Contra Gentiles III, 57). And in fact every being desires its own good for, without it, it cannot attain to its own perfection; thus the intellect, whose proper good is the Truth of that which is, necessarily aspires to the knowledge of That which absolutely is: ‘consequently, for perfect happiness, the intellect needs to reach the very Essence of the First Cause. And thus it will have its perfection through union with God as with that object’ (Summa Theologiae IaIIae, 3, 8). -

Getting Real with Advaita Vedānta: Receiving Bradley J. Malkovsky's

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 31 Celebrating Rāmānuja at 1000: The Heritage and Promise of the Study of Rāmānuja Article 27 in a Christian-Hindu Comparative Theology 2018 Getting Real with Advaita Vedānta: Receiving Bradley J. Malkovsky’s Gifts of Grace Reid B. Locklin St. Michael's College, University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Locklin, Reid B. (2018) "Getting Real with Advaita Vedānta: Receiving Bradley J. Malkovsky’s Gifts of Grace," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 31, Article 27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1704 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Locklin: Getting Real with Advaita Ved?nta: Receiving Bradley J. Malkovsky Getting Real with Advaita Vedānta: Receiving Bradley J. Malkovsky’s Gifts of Grace Reid B. Locklin St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto I recently had the pleasure of spending time volume, through painstaking study of with Joël Dubois’s rich study The Hidden Lives Śaṅkara’s commentaries and significant field of Brahman.1 This work, I was delighted to work. But he also, just as importantly, places discover, begins on its first page with the himself in a lineage of great sages whose academic equivalent of a colophon with number includes our own beloved Bradley J. -

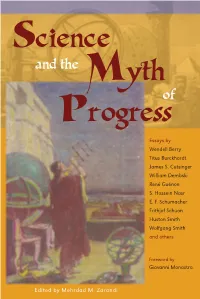

Science and the Myth of Progress Appears As One of Our Selections in the Perennial Philosophy Series

Religion/Philosophy of Science Zarandi Can the knowledge provided by modern science satisfy our need to know the most profound nature of reality and of humanity? Science “The great advantage of this book is that it puts together texts of authors (scientists, philosophers and theologians) whose lucidity about modern and the science goes far beyond emotional reaction and moralist subjectivity; and this ‘tour de force’ is accomplished from within the point of view of the Science yth main traditional religions. Here, Science and Faith are reconciled in an M unexpected way: scientific objectivity is not an issue; but the real issue, where one sees no proof of progress, is whether man is capable of using of modern science properly. A must for the reader who wants to sharpen his or her discernment about modern science.” —Jean-Pierre Lafouge, Marquette University rogress and the and P “Writing as an active research scientist, living in the present Culture of Disbelief created (partly unwittingly) by the science establishment, I can Essays by think of no Research and Development project more significant to the Wendell Berry future of humanity than putting ‘science’ back into its proper place as a Titus Burckhardt part of culture, but not its religion. This book is an excellent contribution Myth to that paramount goal.” James S. Cutsinger —Rustum Roy, Evan Pugh Professor of the Solid State, Emeritus, William Dembski Pennsylvania State University René Guénon “A wonderful collection of essays dealing with the supposed conflict S. Hossein Nasr between religion and science from both a scientific and a metaphysical of E. -

The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co- existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

Copyright © 2013 Pradeep Tilak All Rights Reserved. the Southern

Copyright © 2013 Pradeep Tilak All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. A CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW APOLOGETIC ENGAGEMENT WITH ADVAITA VEDANTA HINDUISM A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Pradeep Tilak May 2013 APPROVAL SHEET A CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW APOLOGETIC ENGAGEMENT WITH ADVAITA VEDANTA HINDUISM Pradeep Tilak Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ James Parker III (Chair) __________________________________________ James D. Chancellor __________________________________________ Theodore J. Cabal Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Sunita. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . vii Chapter 1. CONTEXT OF CHRISTIAN APOLOGETICS . 1 Biblical Mandate . 3 Key Methodological Principles . 5 Dangers in Worldview Apologetics . 15 2. WORLDVIEW CASE STUDY . 21 Hindu Philosophic Tradition . 21 Sankara . 23 Ramanuja . 31 Madhva . 40 Summary . 44 Advaita Vedanta . 47 3. CHRISTIAN APOLOGETICS TO ADVAITA . 49 Examining Methods of Rapprochement . 51 Examining Methods of Antithesis . 57 Recommending a Faithful Approach . 60 Conclusion . 65 4. PROOF: PRESENTING THE CASE . 67 Vedanta’s Basic Beliefs . 68 Christianity’s Basic Beliefs . 79 Apologetic Review . 90 iv Chapter Page Conclusion . 93 5. OFFENSE: HIGHLIGHTING THE STRENGTHS . 94 Vedanta’s Challenge . 94 Christianity’s Challenge . 99 Apologetic Review . 110 Conclusion . 113 6. DEFENSE: RESPONDING TO CHARGES . 115 Vedanta’s Defense . 115 Christianity’s Defense . 121 Apologetic Review . 128 Conclusion . 130 7. APOLOGETIC REVIEW . 132 Metaphysics . 133 Epistemology . 140 Ethics . 147 Conclusion . 153 8. PERSONAL APOLOGETICS . -

Reality As Relational: Scientific, Philosophical and Theological Bases

JPJRS 14/2 ISSN 0972-3331, July 2011 213-244 Reality as Relational: Scientific, Philosophical and Theological Bases Binoy Pichalakkattu, S.J. Regional Theologate, Kalady, Kerala Abstract: This paper attempts attempts to study relationality as an integral aspect of reality. For this the author bases himself on scientific and philosophical perspectives, with a view to understanding theology more adequately. The worldview of science plays a significant role in shaping the philosophical and theological worldview and vice versa. In this paper he starts with the Western perspective on relation and relationality with specific reference to the views of Sto ics, Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. It is followed by the idea of relationality in process philosophy. We bring to light the notion of relationality in Indian Philosophical schools with special emphasis on Sankara’s notion of relation. Relationality is further substantiated by the Vedic myth of Purusa Sukta which underscores the relatedness of the living and non living beings of the universe. We move on to the scientific grounding of relationality with special reference to Newtonian Mechanics, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. It is shown that the concept of relation has been a food for thought in the schools of science and philosophy both in the East and in the West. The scientific and philo sophical grounding of relationality enable us to create an adequate platform for interfacing science, philosophy and theology. The scientifically and philosophically inferred analogical sparks of divine nature on the world also set forth a new sci entific framework for theology and an incentive to rethink its traditional conceptions of Theological doctrines and dogmas. -

1 UNIT 4 ASHRAM MOVEMENT Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1

UNIT 4 ASHRAM MOVEMENT Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Hindu Ashrams 4.3 Christian Ashrams 4.4 Ashrams and Catholic Women Religious 4.5 Protestant Ashrams 4.6 Fundamental Principles and Characteristics of an Ashram 4.7 Some Fundamental Principles and Characteristics of Catholic Ashrams. 4.8 Let Us Sum Up 4.9 Key Words 4.10 Further Readings and References 4.11 Answers to Check Your Progress 4.0 OBJECTIVES The origin of āshrams in India is traced back to the pre-Christian period. Christian Āshrams are of recent origin. Sometimes the motivations behind the establishment of Christian Āshrams were not understood and as a consequence misinterpreted. Our aim in this unit will be to • have a clear idea of what āshrams mean • to understand the convergences and divergences between āshrams of different religious traditions and Christian Āshrams. Therefore to proceed in this regard it is necessary to discuss very briefly the origin of āshrams in India and the origin and development of Christian Āshrams. 4.1 INTRODUCTION The word āsrama is derived from the root śram, to exert oneself. It means a place where austerities are performed, a heritage. It may mean also the action of performing such austerities. There were two currents of thought and life-styles, the brāhmaņic and śramaņic in ancient India long before they came to the surface and became remarkable to the eyes of outsiders like Megasthenes from Greece in the Fourth Century BCE. The brāhmaņic tendency was Aryan, orthodox ritualistic and materialistic while the śramaņic was unorthodox, non-ritualistic and spiritual. -

Toward an Open Eucharist 139

Ritual Participation and Interreligious Dialogue Boundaries, Transgressions and Innovations Edited by Marianne Moyaert and Joris Geldhof Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY RRitualitual PParticipation.indbarticipation.indb iiiiii 22/7/2015/7/2015 22:05:38:05:38 PMPM Chapter 11 T OWARD AN OPEN EUCHARIST R i c h a r d K e a r n e y “ A restricted Eucharist is false. … Whoever ‘ loves ’ his brother has a right to the Eucharist. ”1 — Abhishiktananda, 1998 In this chapter I wish to make a case for an open Eucharist. I will be speaking as a philosopher of Catholic formation paying special attention to two pioneering priests who struggled to share the Body of Christ with people of other faiths. In revisiting their testimonies, I hope to show how such fi gures — and others aft er them — helped pave the way for a less restrictive, and in my view more deeply Christian, approach to the Eucharist. But fi rst, let me off er some remarks from a more personal narrative perspective. 1 D ’ o ù parlez-vous? My Paris teacher and mentor, philosopher Paul Ricoeur, used to greet students entering his seminar with the question: “d ’o ù parlez-vous ? ” Where do you speak from? So let me begin with some stories of Eucharistic sharing and nonsharing which I experienced as a young citizen of “ Catholic Ireland ” in the second half of the twentieth century. First, the sharing. I had a very devout and beautiful mother who took me to Mass every morning, where I served in a local Cork convent as altar boy from the age of seven to eleven. -

Letters to the Editor: an Exchange on Tradition and Sufism

Letters to the Editor: An Exchange on Tradition and Sufism The Malamatiyya, Sufism, and Traditionalist Orthodoxy: A Response to Samuel Bendeck Sotillos’ review of “Sufism and the Way of Blame by Yannis Toussulis” (Sacred Web, Volume 27) By Yannis Toussulis acred Web is a prestigious journal that has accumulated accolades S from a number of distinguished scholars such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Karen Armstrong, and Huston Smith. The journal’s contributors have included luminaries such as Frithjof Schuon, Ananda Coomaras- wamy, William C. Chittick, and a host of others. One would expect that a review of one’s book in such a journal would be non-prejudicial, but, sadly, I do not find this in Mr. Sotillos’ review. Sotillos does not confine himself to a factual critique of the history presented in my book, nor does he point out any logical inconsistencies in my arguments, nor does he offer a penetrating critique of the paradigm that I explore. Instead, the latter is dismissed out-of-hand as an “admix- ture of humanism and modern psychology.” This allegation is odd to me since I am known elsewhere as a critic of both of these intellectual movements despite the fact that I am trained as an academic psychologist. The only reason given for his preemptory dismissal of my work as humanistic and (presumably) psychologistic is that Sotillos disagrees with my conclusions that “the purpose of the malamati path is not perfec- tion in the attainment of the superhuman, but rather a greater human relatedness, greater transparency, and a deeper relationship to the divine” (p.