Report to the Senegal Agricultural Sector Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport EV 2009 Cartes Rev-Mai 2011 Mb MF__Dsdsx

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES ---------- Cellule de Suivi du Programme de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (CSPLP) ---------- Projet d’Appui à la Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté (PASRP) Avec l’appui de l’union européenne ENQUETE VILLAGES DE 2009 SUR L'ACCES AUX SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE Rapport final Dakar, Décembre 2009 SOMMAIRE I. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS _____________________________________________ 3 II. OBJECTIF GLOBAL DE L’ENQUETE VILLAGES __________________________________ 3 III. ORGANISATION ET METHODOLOGIE ________________________________________ 5 III.1 Rationalité ______________________________________________________________ 5 III.2 Stratégie ________________________________________________________________ 5 III.3 Budget et ressources humaines _____________________________________________ 7 III.4 Calendrier des activités ____________________________________________________ 7 III.5 Calcul des indices et classement des communautés rurales _______________________ 9 IV. Analyse des premiers résultats de l’enquête _______________________________ 10 V. ACCES ET EXISTENCE DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE _________________________ 11 VI. Accès et fonctionnalité des services sociaux de base ________________________ 14 VII. Disparités régionales et accès aux services sociaux de base __________________ 16 VII.1 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un lieu de commerce ___________________________ 16 VII.2 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un point d’eau potable _________________________ -

Rn2 Rehabilitation (Section Ndioum-Bakel) and Construction and Maintenance of Roads on the Morphil Island

THE AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : RN2 REHABILITATION (SECTION NDIOUM-BAKEL) AND CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF ROADS ON THE MORPHIL ISLAND COUNTRY : SENEGAL SUMMARY OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Project Team A.I. MOHAMED, Senior Transport Economist, OITC1/SNFO M. A. WADE, Infrastructure Specialist, OITC/SNFO M.L. KINANE, Senior Environmentalist, ONEC.3 S. BAIOD, Environmentalist Consultant, ONEC.3 P.H. SANON, Socio-economist Consultant, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Manager: A. OUMAROU Regional Manager: A. BERNOUSSI Resident Representative : M. NDONGO Division Head: J.K. KABANGUKA 1 Rehabilitation of the RN2 (Ndioum-Bakel section ) and roads SUMMARY OF the ESIA enhancement and asphalting in the Morphil Island Project title : RN2 REHABILITATION (SECTION NDIOUM-BAKEL) AND CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF ROADS ON THE MORPHIL ISLAND Country : SENEGAL Project number : P-SN-DB0-021 Department : OITC Division : OITC.1 1 INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the RN2 and RR40 Roads Development and Pavement Project on the Morphil Island. This summary has been prepared in accordance with the environmental and social assessment guidelines and procedures of the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Senegalese Government for Category 1 projects. The ESIA was developed in 2014 for all road projects and updated in 2015. This summary has been prepared based on environmental and social guidelines and procedures of both countries and the Integrated Backup System of the African Development Bank. It begins with the project description and rationale, followed by the legal and institutional framework in Senegal. A brief description of the main environmental conditions of the project and comparative technical, economic, environmental and social feasibility are then presented. -

Raise Plus-Limited Scope of Work Final Report

RAISE PLUS-LIMITED SCOPE OF WORK FINAL REPORT EVALUATION OF USAID/AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PROGRAM “WULA NAFAA” December 2006 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Weidemann Associates, Inc. EVALUATION OF USAID/AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PROGRAM “WULA NAFAA” FINAL REPORT Submitted by: Weidemann Associates, Inc. Submitted to: USAID/Senegal Contract No.: AEG-I-00-04-00010-00 Period of Performance: November-February 2007 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................................................... iv Evaluation methodology ............................................................................................................. 1 Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... 3 Background and Project Setting................................................................................................ 11 Project Approach ...................................................................................................................... 13 Summary of -

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

SEN FRA REP2 1999.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE Projet GCP/SEN/048/NET Recensement National de l’Agriculture et Système Permanent de Statistiques Agricoles RECENSEMENT NATIONAL DE L’AGRICULTURE 1998-99 Volume 2 Répertoire des villages d’après le pré-recensement de l’agriculture 1997-98 Août 1999 ___________________________________________________________________________ ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE (FAO) Sommaire Données récapitulatives par unité administrative ……………………………………….… 9 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Dakar …………………………………….. 35 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Diourbel …………………………………. 41 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Saint-Louis ………………………….….. 105 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Tambacounda …………………………... 157 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Kaolack …………………………………. 237 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Thiès ……………………………………. 347 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Louga …………………………………… 427 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Fatick …………………………………… 557 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Kolda …………………………………… 617 Carte administrative du Sénégal ………………………………………………………… 727 3 Avant-propos Ce volume 2 des publications sur le pré-recensement de l’agriculture 1997-98 est consacré à la publication d’un répertoire des villages construit à partir des données issues des opérations de collecte du pré-recensement qui ont consisté en une opération de cartographie censitaire et en une enquête sur les ménages ruraux. Le répertoire des villages publié dans ce volume 2 est simplement la liste exhaustive des villages, avec pour chaque village, les valeurs de plusieurs paramètres de taille. A titre d’exemple, l’effectif des concessions rurales, l’effectif des ménages ruraux et l’effectif des ménages ruraux agricoles sont trois variables de taille du village dont les valeurs figurent dans ce répertoire des villages. -

Usaid Wula Nafaa Project Quarterly Report

USAID WULA NAFAA PROJECT QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2010 January 2011 This publication was produced for the United States Agency for International Development by International Resources Group (IRG). USAID WULA NAFAA PROJECT Quarterly Report October-December 2010 Contract No. 685-C-00-08-00063-00 Notice: The points of view expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or of the Government of the USA. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... II 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... 1 2. AGRICULTURE COMPONENT .............................................................. 3 2.1. Targeted results and planned activities .............................................................................. 3 2.2. Progress achieved .................................................................................................................... 5 2.3. Constraints, opportunities, and priorities for next quarter ....................................... 17 3. BIODIVERSITY AND SUSTAINABLE NRM COMPONENT ............ 18 3.1. Targeted results and planned activities ........................................................................... 18 3.2. Progress achieved ................................................................................................................. 20 3.3. Constraints, opportunities, and priorities for next quarter ...................................... -

Projections Démographiques

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL ------------ MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales Division du Recensement et des Statistiques Démographiques Bureau Etat Civil et Projections Démographiques 2013-2063 ANSD-FEVRIER 2016 Projection de la population du Sénégal/MEFP/ANSD-Février 1 2016 INTRODUCTION Les présentes projections démographiques ont été élaborées par l’Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie au cours d’un atelier tenu en mai 2015. Ces projections sont issues d’un large consensus. Elles ont été réalisées avec la participation de techniciens issus d’horizon divers (Ministères de l’Economie des Finances et du Plan, Emploi, Travail, Education, Famille, Agriculture, Elevage, Santé, Jeunes) et UNFPA. Les hypothèses ont été formulées par rapport à une évolution probable des différents facteurs de la dynamique de la population, notamment: La structure de la population, par sexe et par âge ; La structure de la population selon le milieu de résidence (urbaine ou rurale) ; L’Indice synthétique de fécondité comme indicateur de fécondité ; L’espérance de vie ; La structure de la mortalité (à travers l’emploi d’une table‐type de mortalité, celle de Coale & Demeny Nord) ; Le solde migratoire ; Le niveau d’urbanisation. Pour renseigner ces indicateurs, il a fallu recourir à différentes sources de données (RGP 1976 ; RGPH 1988 ; RGPH 2002 et RGPHAE 2013 ; EDS I ; II ; III ; IV et EDS‐MICS 2010‐11) et à des documents de référence en matière de planification sectorielle pour finaliser le travail. Les travaux ont été essentiellement réalisés à l’aide du logiciel SPECTRUM qui est un système de modélisation consolidant différentes composantes dont le modèle DemProj développé par « The Futures Group International ». -

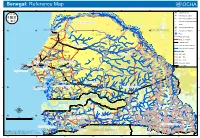

Senegal: Reference Map

Senegal: Reference Map 18°0'0"W 17°0'0"W 16°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 14°0'0"W 13°0'0"W 12°0'0"W !! Podor ! Niandane !^ Capitale d'Etat ! ! Guede Chantiers ! ! Guede Gae Thille-Boubacar ! ! Demet Fanaye ! ! ! Ndiayene ! !Ndioum Oualalde !! ! ! Dodel ! Chef-lieu de région ! Richard-Toll ! Rosso !! Bokhol Gamadji ! Bode Ronkh ! ! Dagana p !! Ndombo Cascas Chef-lieu de département ! !Doumga Madina Ndiatebe ! Ross-Bethio Mbane ! Chef-lieu d'arrondissement ! ! Golere Région de Saint Louis ! Ndiaye ! Meri ! ! ! ! ! Autre !Gnith Salde Diama o ! Mbouba ! !Pete Syer Aéroport international ! ! Galoya Toucouleur Bokke Dialloube ! ! ! Mbolo Birane Agnam Goli Saint-Louis !! ! 16°0'0"N p ! p 16°0'0"N !Gandon Bogal Aéroport secondaire ! Thilogne Nguiguilone Fas Ngom Keur Momar Sarr ! MAURITANIE ! Dabia Mpal ! ! ! ! ! Rao ! Tessekre Forage Boki Diave 0 Port Ndiebene Gandiol ! Lagbar (! ! ! Sakal !Nabadji Route principale Ngueune !Nguermalal ! Sar ! Leona ! ! Mbeuleukhe Niomre ! Pete Ouarak ! !! Route secondaire Mboula Louguere Thioly ! Matam !! ! ! Louga Ourossogui ! Gande ! ! Yang Yang Odobere Ogo ! ! Tiep Kel Gueye Kamb Dodji p ! Chemin de fer ! Coki ! p ! ! ! ! ! ! Gueoul ! !Thiamene ! Mbediene Kanel ! Région de Louga Cours d'eau permanent Ndiagne !Ouro Sidi Kebemer Ngourane Guet Ardo! Boulal Ouarkhokh Linguere ! ! !! ! ! ! ! Tiolom Fall ! Dahra ! Amady Ounare Diokoul Diavrigne ! Sinntiou Bamambe ! ! Kanene Ndiob ! Cours d'eau temporaire Kab Gaye Thiamene ! Ranerou Dendory ! Loro ! !! ! ! ! !Ngandiouf ! ! !Touba Merina Orkadiere Ndande Sagatta ! Sagata Waounde -

Agricultural Policy Analysis Project, Phase Iii

AGRICULTURAL POLICY ANALYSIS PROJECT, PHASE III Sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development Assisting USAID Bureaus, MIssions and Developing Country Governments to Improve Food & Agncultural PoliCies and Make Markets Work Better Prime Contractor Abt Associates Inc Subcontractors Development Alternatives Inc Food Research Institute, Stanford UniVersity Harvard Institute for International Development, Harvard University International SCience and Technology Institute Purdue University Training Resources Group Affiliates AssoCIates for International Resources and Development International Food POlicy Research Institute University of Arizona Project Office 4800 Montgomery Lane Suite 600 Bethesda, MD 20814 Telephone (301) 913 0500 Fax (301) 652-3839 Internet apap3@abtassoc com USAID Contract No LAG 4201 C 00-3052 00 •I I I I I I I PRODUCTION IMPACT REPORT I May 1998 APAP III I Research Report No 1064 I I I I Prepared for I AgrIcultural PolIcy AnalysIs ProJect, Phase III, (AP AP III) USAID Contract No LAG-Q-00-93-00061-00 I Formerly known as Contract No LAG-4201-Q-00-3061-00 I Author Jeffrey Metzel WIth CollaboratIOn of the Umte de Pohhque I AgrIcolelMmIstry of AgrIculture and SAEDIDPDR I I I Repuhhque du Senegal USAIDnoakarandthe MlDistere de I'AgrIculture AgrIcultural PolIcy AnalysIs I Umte de PohtIque AgrIcole (UPA) Project (APAP III) I I I I PRODUCTION IMPACT REPORT I I May 1998 I I Jeffrey Metzel WIth CollaboratIon of the UOIte de PohtIque AgrIcole/Mmlstry of Agriculture I and SAEDnoPDR I I I RSAPIAPAPIUPA Report No 13 I I -

Mapping and Remote Sensing of the Resources of the Republic of Senegal

MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL SDSU-RSI-86-O 1 -Al DIRECTION DE __ Agency for International REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE L'AMENAGEMENT Development DU TERRITOIRE ..i..... MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL For THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL LE MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUP SECRETARIAT D'ETAT A LA DECENTRALISATION Prepared by THE REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS, SOUTH DAKOTA 57007, USA Project Director - Victor I. Myers Chief of Party - Andrew S. Stancioff Authors Geology and Hydrology - Andrew Stancioff Soils/Land Capability - Marc Staljanssens Vegetation/Land Use - Gray Tappan Under Contract To THE UNITED STATED AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING PROJECT CONTRACT N0 -AID/afr-685-0233-C-00-2013-00 Cover Photographs Top Left: A pasture among baobabs on the Bargny Plateau. Top Right: Rice fields and swamp priairesof Basse Casamance. Bottom Left: A portion of a Landsat image of Basse Casamance taken on February 21, 1973 (dry season). Bottom Right: A low altitude, oblique aerial photograph of a series of niayes northeast of Fas Boye. Altitude: 700 m; Date: April 27, 1984. PREFACE Science's only hope of escaping a Tower of Babel calamity is the preparationfrom time to time of works which sumarize and which popularize the endless series of disconnected technical contributions. Carl L. Hubbs 1935 This report contains the results of a 1982-1985 survey of the resources of Senegal for the National Plan for Land Use and Development.