(Cliffs) to Meet the Challenge: the Shiants' Black Rat Eradication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRITISH ISLES 2019 Isle of Skye

SMALL SHIP CRUISING AROUND THE BRITISH ISLES 2019 Isle of Skye contents: Introduction 3 What to Expect 4 Ocean Nova 5 Bird Islands 6-9 Island Hopping in the Hebrides 10-11 Wild Scottish Islands 12-13 MS Serenissima 14-15 Islands on the Edge 16-17 Atlantic Island Odyssey 18-21 Britain’s Islands & Highlands 22-23 2 www.noble-caledonia.co.uk Puffins, Lunga Island DISCOVER THE WONDERS OF THE BRITISH ISLES & IRELAND Make 2019 the year you become better acquainted with the treasures of your homeland. We have many years of experience in designing trips to the hidden corners of our remotest places and yet, every year we discover something new. Although we set sail with a set itinerary it is the unscheduled events that often become the highlight of the journey and our ideally suited vessels will allow access to places larger vessels are unable to venture. Most of us promise ourselves Joining you on board that one day we will see more Our cruises are led by a highly experienced expedition team, including guest of our lovely islands and speakers. For each voyage, we carefully select the best experts in their field, who highlands but the thought of will lead you every step of the way with their knowledge and enthusiasm. These tedious journeys along busy may include ornithologists, naturalists, marine biologists as well as Zodiac drivers roads often leads us instead, and expedition leaders. Through onboard briefings, informal presentations, whilst to jump on an aircraft to some accompanying you ashore and on Zodiac excursions, they will share their in depth distant spot when some of the knowledge of the wildlife, landscape and natural and cultural history of the region. -

Barnacle Geese in the West of Scotland, 1957-1967 HUGH BOYD

96 Wildfowl Barnacle Geese in the west of Scotland, 1957-1967 HUGH BOYD Introduction Such an approach was clearly useless for Twenty years ago it appeared to most of reliable assessment of population changes. the few people with substantial know The only practicable alternative appeared ledge that the Barnacle Goose Branta leu- to be an inspection of the islands from the copsis had decreased considerably as a air, a somewhat costly method about wintering bird in Scotland. That belief which litde was known in Britain. led to a successful attempt to have the After some preliminary exercises in the Barnacle Goose excluded from the list of techniques of aerial observation in 1956, birds that might be shot under the Protec a first survey of the Hebrides was made tion of Birds Act, 1954, effective on 1st in 1957 (Boyd and Radford 1958). A January 1955. On 18th November 1955 second aerial survey of British Barnacle the Secretary of State for Scotland issued Geese, including those in Ireland as well an Order which allowed the geese to be as in Scotland, was conducted in 1959 as shot in the months of December and part of an international assessment of the January on ‘ those islands which are entire population of the species (Boyd situated within any of the counties of 1960). Subsequent surveys were made in Argyll, Inverness and Ross and Cromarty 1961, 1962, 1965 and 1966. This paper and which lie off the mainland of the said has the limited objectives of making the counties and to the west of longitude 5 results of the aerial surveys generally degrees west Only those Barnacle Geese available, using them to find how the frequenting islands off the coast of Suther Hebridean stock of Barnacle Geese has land and those wintering on the Solway fared during the last decade and investi Firth continued to enjoy total legal pro gating whether the lack of total legal tection after November 1955. -

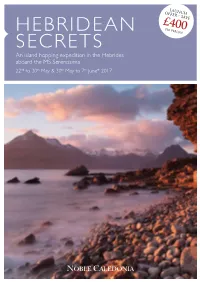

Hebridean Secrets

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE £400 HEBRIDEAN PER PERSON SECRETS An island hopping expedition in the Hebrides aboard the MS Serenissima 22nd to 30th May & 30th May to 7th June* 2017 St Kilda xxxxxxxx ords do not do justice to the spectacular beauty, rich wildlife and fascinating history of the Inner Wand Outer Hebrides which we will explore during this expedition aboard the MS Serenissima. One of Europe’s last true remaining wilderness areas affords the traveller a marvellous island hopping journey through stunning scenery accompanied by spectacular sunsets and prolific birdlife. With our naturalists and local guides we will explore the length and breadth of the isles, and with our nimble Zodiac craft be able to reach some of the most remote and untouched places. Having arranged hundreds of small ship cruises around Scotland, we have realised that everyone takes something different from the experience. Learn something of the island’s history, see their abundant bird and marine life, but above all revel in the timeless enchantment that these islands exude to all those who appreciate the natural world. We are indeed fortunate in having such marvellous places so close to home. Now, more than ever there is a great appreciation for the peace, beauty and culture of this special corner of the UK. Whether your interest lies in horticulture or the natural world, history or bird watching or simply being there to witness the timeless beauty of the islands, this trip will lift the spirits and gladden the heart. WHAT to EXPECT Flexibility is the key to an expedition cruise. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

THE HEBRIDES Explore the Majestic Beauty of the Hebrides Aboard the Ocean Nova 11Th to 18Th May 2019 Gannet in Flight

ISLAND HOPPING IN THE HEBRIDES Explore the majestic beauty of the Hebrides aboard the Ocean Nova 11th to 18th May 2019 Gannet in flight St Kilda Exploring the island of Barra Standing Stones of Callanish, Isle of Lewis ords do not do justice to the spectacular The Itinerary beauty, rich wildlife and fascinating history Isle of Embark the Ocean Nova W St Kilda Lewis Day 1 Oban, Scotland. of the Inner and Outer Hebrides which we will Stornoway this afternoon. Transfers will be provided from OUTER Shiant Islands HEBRIDES Glasgow Central Railway Station and Glasgow explore during this expedition aboard the Ocean Canna International Airport at a fixed time. Enjoy Nova. One of Europe’s last true remaining Barra Loch Scavaig Mingulay SCOTLAND Welcome Drinks and Dinner as we sail this evening. wilderness areas affords the traveller a marvellous Lunga Iona Oban Colonsay Jura Day 2 Barra & Mingulay. This morning we will island hopping journey through stunning scenery INNER HEBRIDES land on Barra which is near the southern tip of accompanied by spectacular sunsets and prolific the Outer Hebrides and visit Castlebay which birdlife. With our naturalists and local guides and curves around the barren rocky hills of a beautiful our fleet of nimble Zodiacs we are able to visit wide bay. Here we find the 15th century Kisimul Castle, seat of the Clan Macneil and a key some of the most remote and uninhabited islands that surround the Scottish coast defensive stronghold situated on a rock in the including St Kilda and Mingulay as well as the small island communities of bay. -

Download Itinerary

JEWELS OF THE SCOTTISH ISLES TRIP CODE ACABJS DEPARTURE 22/05/2022 DURATION INTRODUCTION 8 Days LOCATIONS Chimu Adventures Exclusive - Book and save up to 20% on selected 2022 departures * Scottish Islands Visit no less then 7 Scottish Isles on this incredible expedition. Departing from Greenock on the Scottish West Coast you will venture to the island of Islay, famous for its peaty whiskies. Further north you will see dramatic volcanic formations at Staffa and Rum, Oban and Iona whilst your guest lecturers will give you a rich understanding of the islands geological history. Continuing on to the Outer Hebrides you will see the dramatic cliffs of the St. Kilda archipelago and the rugged scenic island of Orkney - home to some of Europe's oldest preserved dwellings. This incredible spring voyage offers an unforgettable and intimate adventure to the Scottish waters, complete with unique wildlife encounters, spectacular landscapes, and whiskey. *Offers aboard the Ocean Atlantic end 30 November 2021 subject to availability. Not combinable with any other promotion. Applies to voyage only; cabins limited. Subject to availability and currency fluctuations. Further conditions apply, contact us for more information. ITINERARY DAY 1: Embarkation in Greenock Our journey begins in Greenock, where MV Ocean Atlantic is located by the dock. If you arrive early we recommend that you take a walk on the Esplanade, which is a road right down by the water. From the road you can see across the Clyde to the Highlands, Kilcreggan and Helensburgh. Fine views to start our adventure with. Boarding is in the afternoon, where the cabins are designated. -

TSG Outer Hebrides Fieldtrip

TSG Outer Hebrides Fieldtrip 16th – 22nd June 2015 Acknowledgements This field guide was written with the invaluable knowledge and assistance of John Mendum (BGS) and Bob Holdsworth (Durham University). All photos taken by Lucy Campbell if otherwise uncited. Useful Info: Hospitals: • Western Isles Hospital, MacAulay Road, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis HS1 2AF. 01851 704 704 • Uist and Barra Hospital, Balivanich, Benbecula HS7 5LA. 01870 603 603. • St Brendan’s Hospital, Castlebay, Isle of Barra HS9 5XE. 01871 812 021. Emergency Services: • Dial 999 for all, including coastguard/mountain rescue. Outdoor access information: • Sampling/coring : http://www.snh.gov.uk/protecting-scotlands- nature/safeguarding-geodiversity/protecting/scottish-core-code/ • Land Access Rights: http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/access/full%20code.pdf Participants: Lucy Campbell (organiser, University of Leeds) Ake Fagereng (Cardiff University) Phil Resor (Wesleyen University) Steph Walker (Royal Holloway) Sebastian Wex (ETH Zurich) Luke Wedmore (University College London) Friedrich Hawemann (ETH Zurich) Carolyn Pascall (Birkbeck ) Neil Mancktelow (ETH Zurich) John Hammond (Birkbeck) Brigitte Vogt (University of Strathclyde) Andy Emery (Ikon Geopressure) Alexander Lusk (University of Southern California) Vassilis Papanikolaou (University College Dublin) Amicia Lee (University of Leeds) Con Gillen (University of Edinburgh) John Mendum (British Geological Society) 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………4 Trip itinerary..…………………………………………………………………….5 Geological -

SC5616 Ardnamurchan to Shiant Islands

Admiralty Leisure Folio SC5616 Point of Ardnamurchan to Shiant Islands The Notices to Mariners (NMs) listed below apply to the latest edition of SC5616 (3rd Edition) published on 8th February 2018 . L421/18 SCOTLAND — West Coast — Inner Sound — Ru na Lachan NW — Buoyage. Source: Qinetiq Chart: SC5616·6 ETRS89 DATUM Move EfFl.Y.5s, from: 57° 28' ·50N. , 5° 52' ·67W. to: 57° 29' ·13N. , 5° 52' ·54W. Ef from: 57° 28' ·50N. , 5° 52' ·52W. to: 57° 29' ·09N. , 5° 52' ·38W. Chart: SC5616·7 (Panel A, Inner Sound and Sound of Raasay – Northern Part) ETRS89 DATUM Move EfFl.Y.5s, from: 57° 28' ·50N. , 5° 52' ·67W. to: 57° 29' ·13N. , 5° 52' ·54W. Ef from: 57° 28' ·50N. , 5° 52' ·52W. to: 57° 29' ·09N. , 5° 52' ·38W. L862/18 SCOTLAND — West Coast — Gighay N — Marine farm. Source: Marine Scotland Chart: SC5616·13 (Panel A, Oigh Sgeir to Barra) ETRS89 DATUM Insert 57° 01' ·66N. , 7° 19' ·89W. Ë L1542/18 SCOTLAND — West Coast — Rùm — Marine farm. Source: Marine Scotland Chart: SC5616·16 ETRS89 DATUM Insert limit of marine farm, pecked line, joining: (a) 57° 02' ·68N. , 6° 16' ·71W. (b) 57° 02' ·91N. , 6° 16' ·46W. (c) 57° 02' ·70N. , 6° 15' ·72W. (d) 57° 02' ·45N. , 6° 15' ·96W. Page 1 of 35 Ì, within: (a)-(d) above Temporary/Preliminary NMs L2017(T)/18 SCOTLAND — West Coast — Loch Torridon — Scientific instruments. Buoyage. Source: Marine Scotland 1. 79 scientific instruments marked either by yellow surface buoys or unmarked at a minimum depth of 12m, have been established eastward of a line joining the following positions: 57° 34' ·38N. -

The Western Isles of Lewis, Harris, Uists, Benbecula and Barra

The Western Isles of Lewis, Harris, Uists, Benbecula and Barra 1 SEATREK is based in Uig on 5 UIG SANDS RESTAURANT is a newly Let the adventure begin! Lewis, one of the most beautiful opened licensed restaurant with spectacular locations in Britain. We offer views across the beach. Open for lunches unforgettable boat trips around and evening meals. Booking essential. the Hebrides. All welcome, relaxed atmosphere and family Try any of our trips for a great friendly. Timsgarry, Isle of Lewis HS2 9ET. family experience with the Tel: 01851 672334. opportunity of seeing seals, Email: [email protected] basking sharks, dolphins and www.uigsands.co.uk many species of birds. DOUNE BRAES HOTEL: A warm welcome awaits you. We especially 6 Leaving from Miavaig Seatrek RIB Short Trips cater for ‘The Hebridean Way’ for cyclists, walkers and motorcyclists. Harbour, Uig, Isle of Lewis. We have safe overnight storage for bicycles. We offer comfortable Tel: 01851 672469. Sea Eagles & Lagoon Trip .............................. 2 hours accommodation, light meals served through the day and our full www.seatrek.co.uk Island Excursion ................................................. 3 hours evening menu in the evening. Locally sourced produce including Email: [email protected] Customised Trips ............................................... 4 hours our own beef raised on our croft, shellfi sh and local lamb. There’s a Fishing Trip ........................................................... 2 hours Gallan Head Trip ................................................. 2 hours good selection of Malt Whiskies in the Lounge Bar or coffees to go Sea Stacks Trip ................................................... 2 hours whilst you explore the West Side of the Island. Tel: 01851 643252. Email: [email protected] www.doune-braes.co.uk 2 SEA LEWIS BOAT TRIPS: Explore the 7 BLUE PIG CREATIVE SPACE: coastline North and South of Stornoway Carloway’s unique working studio and in our 8.5m Rib. -

Hebrides to the Faroes

HEBRIDES TO THE FAROES EXPLORE THE MAJESTIC BEAUTY OF THE HEBRIDES & THE ENCHANTING FAROE ISLANDS ABOARD THE MS HEBRIDEAN SKY 27TH MAY TO 6TH JUNE 2020 Loch Scavaig ou can travel the world visiting all manner of exotic and wonderful places without realising that some of the finest scenery, fascinating history and most endearing people may be close to Y FAROE ISLANDS home. Nowhere is this truer than around Scotland’s magnificent coastline, an indented landscape of Vestmanna Torshavn enormous natural splendour with offshore islands forming stepping stones into the Atlantic. The sheer SHETLAND diversity of the landscapes and lifestyles will amaze you, as will the spirit and warmth of the small Suduroy ISLANDS communities we will encounter. With our fleet of Zodiacs we are able to visit some of the most remote Unst Fetlar islands that surround the Scottish Coast including Canna, St Kilda, Unst and Fetlar and we also have Lerwick Mousa two days to experience the dramatic landscapes and sparsely populated villages of the Faroe Islands. Fair Isle This is not a cruise in the conventional sense, more an exploration with like-minded companions to St Kilda enjoy the peace and tranquillity of the islands. Learn something of their history, see the abundant Stornoway Shiant SCOTLAND bird and marine life, but above all revel in the timeless enchantment that these islands exude to all Isles Loch Scavaig Aberdeen those who appreciate the natural world. There is no better way to explore this endlessly fascinating Canna and beautiful region than by small ship and, ashore with our local experts, we divide into small Oban groups thereby enjoying a more comprehensive and peaceful experience. -

1966 REPORT of the SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN SOCIETY (Founded in 1960) Proprietor the SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN COMPANY LIMITED (Registered As a Charity} Directors of the Company A

www.schools-hebridean-society.co.uk THE 1966 REPORT OF THE SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN SOCIETY (Founded in 1960) Proprietor THE SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN COMPANY LIMITED (Registered as a Charity} Directors of the Company A. J. ABBOTT. B.A. (Chairman) R. M. FOUNTAINS, B.A. A. S. BATEMAN, B.A. M. J. UNDERBILL, M.A., A. J. C BRADSHAW, B.A. Grad.I.E.R.E. C. M. CHILD, B.A. D. T. VIGAR C. J. DAWSON. B.A. T. J. WILLCOCKS. B.A.I. C. D. FOUNTAINE Hon. Advisers to the Society THE LORD BISHOP OF NORWICH G. L. DAVIES, ESQ.. M.A., Trinity College. Dublin S. L. HAMILTON, ESQ., M.B.E., Inverness I. SUTHERLAND. ESQ., M.A. Headmaster of St. John's School, Leatherhead CONTENTS Page Map of Scotland and (he Isles Foreword by J. S. Grant, M.A.. O.B.E 2 Editorial Comment 3 De Navibus 3 Lewis Expedition 1966 4 Harris Expedition 1966 24 Book Review 34 Jura Expedition 1966 35 Colonsay Expedition 1966 42 Dingle Expedition 1966 53 Ornithological Summary 1966 56 Plans for 1967 61 Acknowledgements 61 Expedition Members .. 62 S.H.S. Tie order form 72 The Editor of the Report is C. J. Dawson FOREWORD EDITORIAL COMMENT By J. S. Grant, Esq., M.A., O.B.E., As 1 have discovered, it is by no means easy to maintain the high Chairman of the Crofters Commission standard set by Martin Child, who built this publication up from nothing to what it is now. Fortunately he has not left the scene I sometimes think. -

Shiant Isles, United Kingdom

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2018, 2(3): 346-347 © 2018 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2018.03.15 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Shiant Isles, United Kingdom Liu, C.* Shi, R. X. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Keywords: Shiant Isles; United Kingdom; Scotland; Garbh Eilean; data encyclopedia The Shiant Isles of Scotland is located from 57°52′45″N to 57°54′30″N, 6°25′3″W to 6°19′21″W[1–2]. It is in the Minch Strait and belongs to Outer Hebrides[3], separated 5.34 km from Lewis Island[4] at its northwest, 32 km from the Scotland at its east, and 19 km from Skye at its south (Figures 1-2). The Shi- ant Isles are private[2]. The Shiant Isles consist of 3 main islands, and 18 small isles and rocks. The main islands are Garbh Eilean[5], Eilean an Taighe[6], and Eilean Mhuire[7]. The small islands and rocks includes Galca Mor, Galta Beag, Sgeir Mhic a’Ghobha, Sgeir Mianais, Bodach, Sgeir na Figure 1 Geo-location of Shiant Isles (.kmz format) Ruideag, Stacan Laidir, and Damhag, etc.[8–9] (Table 1). The total area of the Shiant Isles is 2.15 km2 and the coastline is 17.98 km. In the Shiant Isles, Garbh Eilean is the biggest isle with an area of 0.98 km2, Eilean an Taighe is the second biggest one with an area of 0.66 km2, and Eilean Mhuire is the third one with an area of 0.42 km2.