Identifying Social Network Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2019 In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group Christina A. Barber IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Barber, Christina A., "In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group" (2019). Academic Research and Dissertations. 29. https://digitalmaine.com/academic/29 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE MOUTH OF THE WOOLF: THE POSTHUMANISTIC THEATER OF THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP Christina Anne Barber Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy August, 2019 ii Accepted by the faculty at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Simonetta Moro, PhD Director of School & Vice President for Academic Affairs Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: George Smith, PhD Founder & President Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: Conny Bogaard, PhD Executive Director Western Kansas Community Foundation iii © 2019 Christina Anne Barber ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv Mother of Romans, joy of gods and men, Venus, life-giver, who under planet and star visits the ship-clad sea, the grain-clothed land always, for through you all that’s born and breathes is gotten, created, brought forth to see the sun, Lady, the storms and clouds of heaven shun you, You and your advent; Earth, sweet magic-maker, sends up her flowers for you, broad Ocean smiles, and peace glows in the light that fills the sky. -

November 2-5 2017

LITERARY FESTIVAL NOVEMBER 2-5 2017 An International Festival Celebrating Literature, Ideas and Creativity. CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM FOR TICKETS VISIT CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM CALL 843.723.9912 1 WELCOME Welcome to an exciting new trans-Atlantic literary festival hosted by two remarkable sites named Charleston. The partnership between two locations with the same name, separated by a vast oceanic expanse, is no mere coincidence. Through the past several centuries, both Charleston, SC and Charleston, Sussex have been home to extraordinary scholars, authors and artists. A collaborative literary festival is a natural and timely expression of their shared legacies. UK © C Luke Charleston, Established in 1748, the Charleston Library Society is the oldest cultural institution in the South and the country’s second oldest circulating library. Boasting four signers of the Declaration of Independence and hosting recent presentations by internationally acclaimed scholars such as David McCullough, Jon Meacham, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, its collections and programs reflect the history of intellectual curiosity in America. The Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, England was home to the A Hesslenberg Charleston © Festival famed Bloomsbury group - influential, forward-looking artists, writers, and thinkers, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and frequent guests Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot. For almost thirty years, Charleston has offered one of the most well-respected literary festivals in Europe, where innovation and inspiration thrive. This year’s Charleston to Charleston Literary Festival inaugurates a partnership dedicated to literature, ideas, and creativity. With venues as historic as the society itself, the new festival will share Charleston’s famed Southern hospitality while offering vibrant insights from contemporary speakers from around the globe. -

Diaghilev and London

Diaghilev and London, A Talk by Graham Bennett, Crouch End and District U3A member We are not exactly the best of friends with Russia these days - But just over a century ago, Russia exported something that actually transformed the cultural life of London. This talk is about a quite extraordinary Russian Impresario and two equally extraordinary women who were part of his project The project was a Russian Dance Company that created a revolution in the world of dance, and London was to play a big part in its success. This company is the Ballet Russes. The impresario is Serge Diaghilev, born in 1872 in Perm in deepest Russia, who would create the Ballet Russes. Lydia Lopokova from St Petersburg, born in 1892, one of Diaghilev's star ballerinas. And last but not least, our very own Hilda Munnings from Wanstead in East London, born in 1896. Also to become a vitally important member of the company The story starts in St Petersburg in 1901, the heart of the Russian Empire, at the famous Mariinsky Theatre. Their choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Tchaikovsky had already created masterpieces such as The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. These are such familiar names to us today but they were virtually unknown outside Russia at that time. Over in England we were still having a jolly knees up and sing-along at the Music Hall and even in France, ballet had degenerated to a pale shadow of its former glory. In 1901, Lydia Lopokova, just 9 years old, auditioned for a place at the prestigious Imperial Theatre School in St Petersburg. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

A Bloomsbury Chronology 1866 Roger Fry born 1877 Desmond Maccarthy born 1879 E.M. Forster born Vanessa Stephen born 1880 Lytton Strachey born Thoby Stephen born Saxon Sydney-Turner born Leonard Woolf born 1881 Clive Bell born 1882 Virginia Stephen born Mary Warre-Cornish born 1883 J.M. Keynes born Adrian Stephen born 1885 Duncan Grant born Roger Fry enters King's College, Cambridge 1888 Roger Fry obtains a First Class honours in natural sciences and decides to study painting xx A Bloomsbury Chronology 1892 Roger Fry studies painting in Paris David Garnett born 1893 Dora Carrington born 1894 Roger Fry gives university extension lectures at Cambridge mainly on Italian art Desmond Maccarthy enters Trinity College, Cambridge 1895 Death of Mrs Leslie Stephen Virginia Stephen's first breakdown 1896 Roger Fry and Helen Coombe married 1897 E.M. Forster enters King's College, Cambridge Desmond MacCarthy leaves Trinity College Virginia Stephen attends Greek and history classes at King's College, London 1899 Roger Fry: Giovanni Bellini Clive Bell, Thoby Stephen, Lytton Strachey, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Leonard Woolf all enter Trinity College, Cambridge The Midnight Society - a 'reading society' - founded at Trinity by Bell, Sydney-Turner, Stephen, and Woolf 1900 Roger Fry gives university extension lectures on art at Cambridge 1go1 Roger Fry becomes art critic for the Athenaeum Vanessa Stephen enters the Royal Academy Schools E.M. Forster leaves Cambridge, travels in Italy and Greece, begins A Room with a View 1902 Duncan Grant attends the Westminster Art School Leonard Woolf, Saxon Sydney-Turner, and Lytton Strachey elected to 'The A Bloomsbury Chronology XXI Apostles' (older members include Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy, E.M. -

Lynn Garafola Most Fruitful Experiments in His Company's History

• ON 11 JANUARY 1916 DIAGHILEV and his Ballets Russessteamed into New York harbor for the first of two lengthy tours of the United States. Both began in New York, THE then crisscrossed the country, giving Americans in no fewer than fifty-one cities a taste of Diaghilev's fabled entertainment. The company that made these 1916-1917 tours was BALLETS RUSSES different from the one Europeans knew. There were few stars and many new faces and a repertory that gave only a hint of Diaghilev's growing experimentalism. The Ballets Russes IN AMERICA never triumphed in the United States, as it had in Europe, nor did it immediately influence the course of American ballet. But the tours set in motion changes within the Ballets Russes itself that had lasting consequences. Thanks to American dollars, Diaghilev rebuilt the company temporaril y disbanded by World War I while conducting some of the Lynn Garafola most fruitful experiments in his company's history. Those sa me dollars paid for the only ballet to have its premiere in the New World-Vaslav Nijinsky's Till Eulenspiegel. In size, personnel, and social relations, the Ballets Russes of the American tours marked the bi rth of Diaghilev's postwar company. Diaghilev had long toyed with the idea of an American tour. But only in 1914, when debt threatened the very life of his enterprise, did he take steps to convert the idea into a reality. "Have had several interviews ... Diaghileff about Ballet for New York," Addie Kahn wired her husband, Otto, chairman of the Metropolitan Opera's board of directors, from London on 18 July 1914: [Is] most insistent troupe shou ld go America this winter for urgent reasons too complicated to cable upon which largely depend continuance of organization. -

Berwick Church and the Bloomsbury Murals

Berwick Church and the Bloomsbury Murals: Writing and Research by Students from the University of Sussex Spring 2020 Preface Hope Wolf Berwick and Beyond: Bee Hendry Abstract Forms and International References in Duncan Grant’s Designs for the Church Murals Heartfelt Summer Rupert Tarrant Country and City: Charise Niarchos Mrs Sandilands and the Making of the Berwick Murals A ‘space for us’: Scarlett May Walker Local Communities and their Heritage ‘Be content with the view in front of us’: Grace van der Byl Williams An Installation Designed for St Michael and All Angels Church Preface Hope Wolf This pamphlet was made by third-year students from the School of English at the University of Sussex. They took part in a course called ‘Arts and Community’, the aim of which is to work with cultural organisations in order to bring undergraduate research to an audience outside of the university. The course focuses on a different place and project each year it runs, and in the spring of 2020 students engaged with an initiative, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, to conserve the Berwick Church murals. They sought to tell new stories about murals and the Berwick site using archival documents at the Keep (East Sussex Record Office), drafts of the murals at both Charleston and the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne, oral history interviews gathered as part of the HLF project, writing from the fields of literature, art history and geography, and on-site observations of the church and its environs (we walked from Berwick to Charleston Farmhouse via Alciston). The course was linked to the Centre for Modernist Studies research project on Sussex Modernism, and connections were made between other cultural sites in the area, both on and off the map. -

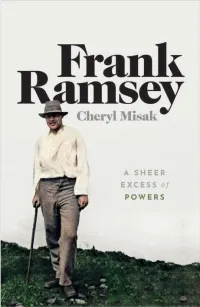

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Galbraith on Keynes

Galbraith on Keynes In a classic, The“ Age of Uncertainty”, the author, late economist John Kenneth Galbraith, writes on Lord Keynes. “Keynes was born in 1883, the year that Karl Marx died. His mother, Florence Ada Keynes, a woman of high intelligence, was diligent in good works, a respected community leader and, in late life, the mayor of < ?xml:namespace prefix = st1 ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:smarttags" />Cambridge. His father, John Neville Keynes, was an economist, logician and for some fifteen years the Registrary, which is to say the chief administrative officer of the University of Cambridge. Maynard, as he was always known to friends, went to Eton, where his first interest was in mathematics. Then he went to King's College, after Trinity the most prestigious of the Cambridge colleges and the one noted especially for its economists. Keynes was to add both to its prestige in economics and, as its bursar, to its wealth. Churchill held – where I confess escapes me – that great men usually have unhappy childhoods. At both Eton and Cambridge, Keynes, by his own account and that of his contemporaries, was exceedingly happy. The point could be important. Keynes never sought to change the world out of any sense of personal dissatisfaction or discontent. Marx swore that the bourgeoisie would suffer for his poverty and his carbuncles. Keynes experienced neither poverty nor boils. For him the world was excellent. While at King's, Keynes was one of a group of ardent young intellectuals which included Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell. All, with wives – Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell- and lovers, would assemble later in London as the Bloomsbury Group. -

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches the First Leg of The

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches The first leg of the legendary 18-miler ended with Shetland ponies in the village of Firle. The waist-high animals were unendingly friendly in their welcome, ambling over from their grazing spots to willingly be petted. Needless to say, they were an instant hit. “Can we ride them?” I had half-jokingly asked when first told that we would be encountering these cute-tastic creatures. My question had been met with chuckling doubt as to the animals’ ability to hold us, but there is an even more compelling reason not to saddle up one of these little beasts. Shetland folklore, naturally obligated to make mention of the distinctive animals, brings us the njuggle. A folkloric waterhorse inclined to potentially malevolent pranks, the njuggle is a nuisance primarily to millers in its harmlessly playful incarnation, hiding under the mill and interfering with its operation but easily banished with a lump of burning peat. Its more sinister side resembles its Celtic analog, the kelpie. In the form of a splendid Shetland pony, the njuggle wanders about until some unwary weary traveler, perhaps lured by the ill-intent of the creature or perhaps just by unlucky circumstance, mounts its back. With this, the njuggle gallops headlong into the nearest loch, often drowning the hapless traveler who ought to have known better than to accept a ride from a Shetland pony. There were no lochs nearby, only the river Ouse. Either way, it was a less fanciful instinct that kept me off the ponies’ backs; but their deep eyes and calm acquiescence to human overtures of friendship seemed to me a perfect lure. -

A Short Guide to Keynes and German Translations of His Works, Especially the General Theory

518297‐LLP‐2011‐IT‐ERASMUS‐FEXI A SHORT GUIDE TO KEYNES AND GERMAN TRANSLATIONS OF HIS WORKS, ESPECIALLY THE GENERAL THEORY NIELS GEIGER UNIVERSITÄT HOHENHEIM STUTTGART, GERMANY [email protected] ABSTRACT This guide aims at providing an introduction to the general context within which the translation of Keynes’s works into German, especially the most interesting case of the General Theory is to be seen. The guide thus relates to the related research paper by Harald Hagemann. The guide provides short overviews on Keynes’s biography, his works (including a short overview of German translations), and his legacy. Some exercises and a short test conclude the guide. “The study of economics does not seem to require any specialised gifts of an unusually high order. Is it not, intellectually regarded, a very easy subject compared with the higher branches of philosophy and pure science? Yet good, or even competent, economists are the rarest of birds. An easy subject at which very few excel! The paradox finds its explanation, perhaps, in that the master-economist must possess a rare combination of gifts. He must reach a high standard in several different directions and must combine talents not often found together. He must be mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher - in some degree. He must understand symbols and speak in words. He must contemplate the particular in terms of the general, and touch abstract and concrete in the same flight of thought. He must study the present in the light of the past for the purposes of the future. No part of man's nature or his institutions must lie entirely outside his regard. -

Things to Look Out

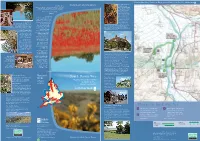

NATIONAL TRAIL © Property of The Charleston Trust Exploring Bloomsbury Country; the Downs between Rodmell and Berwick Wander the Wide Green Downs Green Wide the Wander The Bloomsbury by the same route. route. same the by meadows to Virginia Woolf’s House at Rodmell. It returns It Rodmell. at House Woolf’s Virginia to meadows Group of artists, Ouse, then follows the riverbank and across the flood the across and riverbank the follows then Ouse, writers, and intellectuals From Southease station this route crosses the River the crosses route this station Southease From included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, About 4 miles (6 km), 2 hours 2 km), (6 miles 4 About EM Forster, Duncan A Stroll Stroll A Grant, Lytton Strachey, and the economist John come prepared! prepared! come Maynard-Keynes who especially in rain or low cloud, so cloud, low or rain in especially lived at Tilton. Many of exposed in cold windy weather, windy cold in exposed the Bloomsbury Group of the Downs can be surprisingly be can Downs the of Firle if preferred. if Firle formed a small and appropriate footwear. The tops The footwear. appropriate Station. There is a short cut back to back cut short a is There Station. unique community in can be muddy, so wear so muddy, be can South Downs Way back to Southease to back Way Downs South the Rodmell/Firle area winter parts of all the walks the all of parts winter Downs to Bopeep then follows the follows then Bopeep to Downs between the two world wars - ironically they became longer walks. -

The Image of Keynes. Duncan Grant and John Maynard

KEYNES IN KING’S COLLEGE Julien Domercq (King’s College, Cambridge), The Image of Keynes. Duncan Grant and John Maynard Keynes were in their early twenties when they spent two months together at the end of the summer of 1908 in splendid isolation on the island of Hoy in the Orkneys, an archipelago to the very north of Scotland. However, this two-month holiday was far from being only a romantic idyll. Keynes revisited his Treatise on Probability, the Fellowship Dissertation which had failed to win him a prize-fellowship at King’s College, Cambridge, while Grant produced several drawings and paintings of the barren and inhospitable landscape, as well as his striking Portrait of John Maynard Keynes (1908). Reproduced in almost all publications on Keynes and on Grant, this intimate portrait, owned by King's since 1958, has often been described as one of Grant’s ‘most vivid likenesses’. Centred on this portrait, the talk claims that it was painted at a pivotal moment in the development of Grant and Keynes’s professional, and indeed emotional, lives, and argues that its making had a key influence on the development of Keynes’s interest in art. Julien Domercq is now the Vivmar Curatorial Assistant at the National Gallery in London, where he is one of the curators responsible for Post-1800 paintings. Julien graduated with a BA and an MPhil in History of Art from the University of Cambridge and is currently completing his PhD at King’s College, Cambridge, funded by a Gates Cambridge scholarship. His thesis, ‘From Noble to Ignoble Savage: Representing the Pacific, c.