Berwick Church and the Bloomsbury Murals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2-5 2017

LITERARY FESTIVAL NOVEMBER 2-5 2017 An International Festival Celebrating Literature, Ideas and Creativity. CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM FOR TICKETS VISIT CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM CALL 843.723.9912 1 WELCOME Welcome to an exciting new trans-Atlantic literary festival hosted by two remarkable sites named Charleston. The partnership between two locations with the same name, separated by a vast oceanic expanse, is no mere coincidence. Through the past several centuries, both Charleston, SC and Charleston, Sussex have been home to extraordinary scholars, authors and artists. A collaborative literary festival is a natural and timely expression of their shared legacies. UK © C Luke Charleston, Established in 1748, the Charleston Library Society is the oldest cultural institution in the South and the country’s second oldest circulating library. Boasting four signers of the Declaration of Independence and hosting recent presentations by internationally acclaimed scholars such as David McCullough, Jon Meacham, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, its collections and programs reflect the history of intellectual curiosity in America. The Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, England was home to the A Hesslenberg Charleston © Festival famed Bloomsbury group - influential, forward-looking artists, writers, and thinkers, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and frequent guests Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot. For almost thirty years, Charleston has offered one of the most well-respected literary festivals in Europe, where innovation and inspiration thrive. This year’s Charleston to Charleston Literary Festival inaugurates a partnership dedicated to literature, ideas, and creativity. With venues as historic as the society itself, the new festival will share Charleston’s famed Southern hospitality while offering vibrant insights from contemporary speakers from around the globe. -

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches the First Leg of The

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches The first leg of the legendary 18-miler ended with Shetland ponies in the village of Firle. The waist-high animals were unendingly friendly in their welcome, ambling over from their grazing spots to willingly be petted. Needless to say, they were an instant hit. “Can we ride them?” I had half-jokingly asked when first told that we would be encountering these cute-tastic creatures. My question had been met with chuckling doubt as to the animals’ ability to hold us, but there is an even more compelling reason not to saddle up one of these little beasts. Shetland folklore, naturally obligated to make mention of the distinctive animals, brings us the njuggle. A folkloric waterhorse inclined to potentially malevolent pranks, the njuggle is a nuisance primarily to millers in its harmlessly playful incarnation, hiding under the mill and interfering with its operation but easily banished with a lump of burning peat. Its more sinister side resembles its Celtic analog, the kelpie. In the form of a splendid Shetland pony, the njuggle wanders about until some unwary weary traveler, perhaps lured by the ill-intent of the creature or perhaps just by unlucky circumstance, mounts its back. With this, the njuggle gallops headlong into the nearest loch, often drowning the hapless traveler who ought to have known better than to accept a ride from a Shetland pony. There were no lochs nearby, only the river Ouse. Either way, it was a less fanciful instinct that kept me off the ponies’ backs; but their deep eyes and calm acquiescence to human overtures of friendship seemed to me a perfect lure. -

Things to Look Out

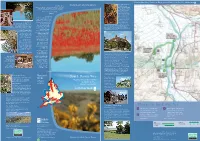

NATIONAL TRAIL © Property of The Charleston Trust Exploring Bloomsbury Country; the Downs between Rodmell and Berwick Wander the Wide Green Downs Green Wide the Wander The Bloomsbury by the same route. route. same the by meadows to Virginia Woolf’s House at Rodmell. It returns It Rodmell. at House Woolf’s Virginia to meadows Group of artists, Ouse, then follows the riverbank and across the flood the across and riverbank the follows then Ouse, writers, and intellectuals From Southease station this route crosses the River the crosses route this station Southease From included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, About 4 miles (6 km), 2 hours 2 km), (6 miles 4 About EM Forster, Duncan A Stroll Stroll A Grant, Lytton Strachey, and the economist John come prepared! prepared! come Maynard-Keynes who especially in rain or low cloud, so cloud, low or rain in especially lived at Tilton. Many of exposed in cold windy weather, windy cold in exposed the Bloomsbury Group of the Downs can be surprisingly be can Downs the of Firle if preferred. if Firle formed a small and appropriate footwear. The tops The footwear. appropriate Station. There is a short cut back to back cut short a is There Station. unique community in can be muddy, so wear so muddy, be can South Downs Way back to Southease to back Way Downs South the Rodmell/Firle area winter parts of all the walks the all of parts winter Downs to Bopeep then follows the follows then Bopeep to Downs between the two world wars - ironically they became longer walks. -

The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group Destinations: South Downs & England Trip code: AWHBB HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Follow in the footsteps of the group of early 20th century influential authors, artists, philosophers and intellectuals known as the Bloomsbury Set. This bohemian group included Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. You’ll enjoy visits to Charleston – their farmhouse country retreat, the world-famous gardens of Sissinghurst and Knole House – one of England’s largest houses. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High-quality Full Board en-suite accommodation and excellent food in our country house • The guidance and services of our knowledgeable HF Holidays Leader, ensuring you get the most from your holiday • All transport on touring days on a comfortable, good-quality mini-coach • All admissions to venues/attractions that form part of your holiday itinerary, excluding National Trust and English Heritage properties HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Charleston - the farmhouse home of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant • Knole House - one of England’s largest houses www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Sissinghurst - Vita Sackville-West's world-famous garden TRIP SUITABILITY Our Heritage Tours are your opportunity to immerse yourself in an area of history that interests you, at the same time as exploring the local area with a group of like-minded people. Each day our leaders will provide fascinating commentary on the places visited and share their knowledge with you. This holiday involves active sightseeing so please come prepared to spend most of the day on your feet. We may walk up to 3 miles (5km) each day at the various venues and attractions we visit. -

November 2-5 2017

LITERARY FESTIVAL NOVEMBER 2-5 2017 An International Festival Celebrating Literature, Ideas and Creativity. CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM FOR TICKETS VISIT CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM CALL 843.723.9912 1 WELCOME Welcome to an exciting new trans-Atlantic literary festival hosted by two remarkable sites named Charleston. The partnership between two locations with the same name, separated by a vast oceanic expanse, is no mere coincidence. Through the past several centuries, both Charleston, SC and Charleston, Sussex have been home to extraordinary scholars, authors and artists. A collaborative literary festival is a natural and timely expression of their shared legacies. UK © C Luke Charleston, Established in 1748, the Charleston Library Society is the oldest cultural institution in the South and the country’s second oldest circulating library. Boasting four signers of the Declaration of Independence and hosting recent presentations by internationally acclaimed scholars such as David McCullough, Jon Meacham, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, its collections and programs reflect the history of intellectual curiosity in America. The Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, England was home to the A Hesslenberg Charleston © Festival famed Bloomsbury group - influential, forward-looking artists, writers, and thinkers, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and frequent guests Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot. For almost thirty years, Charleston has offered one of the most well-respected literary festivals in Europe, where innovation and inspiration thrive. This year’s Charleston to Charleston Literary Festival inaugurates a partnership dedicated to literature, ideas, and creativity. With venues as historic as the society itself, the new festival will share Charleston’s famed Southern hospitality while offering vibrant insights from contemporary speakers from around the globe. -

For Immediate Release 24 September 2004 BLOOMSBURY COMES TO

For immediate release 24 September 2004 Contact: Karon Read +44 (0) 207 389 2964 [email protected] BLOOMSBURY COMES TO CHRISTIE’S Beautiful Collection of Works by Leading Members of the Bloomsbury Group including Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry at Christie’s London in November 20th Century British and Irish Art including Property from The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. Christie’s London 19 November 2004 London – One of the most significant groups of paintings by the Bloomsbury circle ever to come to auction are among works from The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc’s corporate collection to be sold at Christie’s as part of the 20th Century British & Irish Art sale on 19 November 2004. The group features 40 works including examples by Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry, leading members of the avant-garde Bloomsbury Group and among the first British artists to exhibit with Picasso and Matisse. The Collection also includes 30 works by other 20th Century British artists including Ivon Hitchens, Henry Moore, Lucien Pissarro, Sir Stanley Spencer and Walter Sickert. The Collection is expected to fetch in excess of £1million. Vanessa Bell’s work of 1940, The Dining Room Window, Charleston (estimate: £30,000-50,000), depicts an intimate family scene with Duncan Grant seated at a table with their daughter, Angelica, pausing in quiet contemplation before her marriage to David Garnett. In Duncan Grant’s Still Life with Opel, dating from 1937 (estimate: £30,000-50,000) the subject is painted against a backdrop of the three rejected murals which he painted for the Queen Mary liner in 1935. -

2017 Sussex Modernism Catal

Published to accompany the exhibition at CONTENTS Two Temple Place, London 28th January – 23rd April 2017 Exhibition curated by Dr Hope Wolf Foreword 04 Published in 2017 by Two Temple Place The Making of Sussex Modernism 2 Temple Place Dr. Hope Wolf, University of Sussex 08 London WC2R 3BD Sussex: A Modern Inspiration 56 Copyright © Two Temple Place Acknowledgements 68 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-9570628-6-3 Designed and produced by: NA Creative www.na-creative.co.uk Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion Produced by The Bulldog Trust in partnership with: Charleston, De La Warr Pavilion, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, Farleys House & Gallery, Jerwood Gallery, Pallant House Gallery, Towner Art Gallery, Royal Pavilion & Museums Brighton & Hove, University of Sussex, West Dean College 02 03 FOREWORD truly extraordinary cultural heritage of the counties of East and West Sussex and the breadth and diversity of the artists who made this area Charles M. R. Hoare, Chairman of Trustees, their home during the first half of the twentieth century. The Bulldog Trust We are delighted to have collaborated with nine celebrated museums and galleries in the production of this exhibition: Charleston, De La Warr Pavilion, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, Farleys House & The Bulldog Trust is delighted to welcome you to Sussex Modernism: Gallery, Jerwood Gallery, Pallant House Gallery, Towner Art Gallery, Retreat and Rebellion, our sixth Winter Exhibition at Two Temple Place. Royal Pavilion & Museums Brighton & Hove and West Dean. We are very grateful for their generosity in lending from their spectacular Two Temple Place was originally built as the estate office of William collections and for the time and knowledge they have shared, with Waldorf Astor, designed by eminent Gothic Revival architect, John particular thanks to Nathaniel Hepburn at Ditchling Museum of Art Loughborugh Pearson. -

East Sussex Cultural Strategy 2013 – 2023

East Sussex Cultural Strategy 2013 – 2023 A County of distinction, igniting the power of culture A ten year partnership framework produced by East Sussex County Council on behalf of government agencies and services, key cultural organisations and cultural leaders. East Sussex Cultural Strategy 2013 – 2023 East Sussex Cultural Strategy 2013 – 2023 The Vision – where Contents we want to be The Vision – where we want to be . 3 By 2023 we will be able to say that: used as a gateway to improved physical and mental health and wellbeing, higher educational East Sussex has a distinctive character: it is attainment, skills development, employment Executive Summary . 5 as well known for its excellent, innovative and and growing social capital. varied cultural offer as it is for its beautiful landscapes, its history and its coastline. It is Creative people choose to live here and creative 1. Introduction . 9 a County which understands, is proud of and businesses thrive because they are inspired by actively values its cultural assets. the County and are supported wisely. Planning, investment and marketing decisions at all levels 2. Where are we now? . 12 All sorts of businesses choose to establish shore up and enable the growth of creative themselves in East Sussex because the businesses. Success breeds success and the County will offer their employees a rich cultural and creative sector is expanding. 3. The Priorities . 19 cultural offer and the quality of life which will ensure that they can attract and retain There is a well packaged, clearly signposted, the workforce they need. regularly refreshed cultural tourism offer: Priority 1 . -

The Bloomsbury Group

THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP Mgr. Velid Beganović PERSONAL AND COLLECTIVE GEOGRAPHIES • European modernist hotspots of the first half of the 20th century: Paris London Berlin Munich Prague Vienna Moscow PARIS • Fine Arts: (among others) Impressionists, Fauvists, Cubists, etc. • Literature: The Left Bank community & The Lost Generation BERLIN • Fritz Lang‘s circle & • The 30s poets A still from Lang‘s Metropolis (1927) PRAGUE Rossler FUNKE MOSCOW Russian Futurists, Constractivists and Suprematists LIUBOV POPOVA MALEVICH LONDON THE ROOTS OF THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP The four Stephen Siblings: Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa and Virginia JULIA PRINSEP STEPHEN, FORMERLY DUCKWORTH (1846 – 1895) LESLIE STEPHEN (1832 – 1904) 51 GORDON SQUARE, BLOOMSBURY THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP TIMELINE • 1904-1914: „Old Bloomsbury“ • 1914-1919: Conscientious Objectors, Garsington, Charleston Farm House and Monks House • 1920-1941: Fruitful years; „Us old and them new“; 1930s decline; deaths TIMELINE • 1900s • 1904 • Vanessa Stephen (Bell) moves to Gordon Square, Bloomsbury with her brothers and sister. • 1905 • ‘Friday Club’ founded by Vanessa Bell. With the literary ‘Thursday Evenings’ organised by her brother Thoby, these groups formed the origins of the Bloomsbury Group. • 1906 • Duncan Grant spends a year in Paris studying at La Palette, the art school run by Jacques- Emile Blanche. • 1907 • Vanessa marries Clive Bell. • 1910s • 1910 • Roger Fry meets Vanessa and Clive Bell. • Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition at Grafton Galleries, organised by Roger Fry. • 1911 • Borough Polytechnic Murals. • Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry become lovers. • 1912 • Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, organised by Roger Fry opens at Grafton Galleries. • 1913 • Opening of the Omega Workshops. THE DREADNAUGHT HOAX Virginia Stephen • 1914 • Beginning of relationship between Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. -

Teachers' Resource

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE BEYOND BLOOMSBURY DESIGNS OF THE OMEGA WORKSHOPS 1913–19 CONTENTS WELCOME 1 BEYOND BLOOMSBURY: 2 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE OMEGA WORKSHOPS SHOPPING AT THE OMEGA 4 PURE VISUAL MUSIC: 6 MUSICAL THEMES IN BLOOMSBURY AND BEYOND ALPHA TO OMEGA: THE 10 BLOOMSBURY AUTHORS LES ATELIERS OMEGA ET 14 LE POST-IMPRESSIONNISME LEARNING RECOURCE CD 17 Cover: Pamela Design attributed to Duncan Grant, 1913, printed linen Victoria and Albert Museum, London Below: White (three of five colourways) Design attributed to Vanessa Bell, 1913, printed linen Victoria and Albert Museum, London WELCOME The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. The Teachers’ Resouces and Image CDs have proved immensely popular in their first year; my thanks go to all those who have contributed to this success and to those who have given us valuable feedback. In future we hope to extend the range of resources to include material based on Masterpieces in The Courtauld collection which I hope will prove to be both useful and inspiring. With best wishes, Henrietta Hine Head of Public Programmes The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House Strand, London WC2R 0RN BEYOND BLOOMSBURY: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE OMEGA WORKSHOPS Image: Four-fold screen with Lily pond design Duncan Grant, 1913-14, Oil on wood 181.6 x 242.4cm Established in 1913 by the painter and Wyndham Lewis, Frederick Etchells, influential art critic Roger Fry, the Omega Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Winifred Workshops were an experimental design Gill – the remarkable young woman collective, whose members included who ran the Workshops from the start of Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and other the War until 1916. -

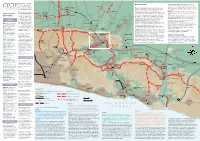

CYCLE RIDES Cuckmere Haven and Friston Forest a Very Easy Short Concrete Path Runs from the Car Park by the A259 at Exceat CYCLE Cyclists and Horse Riders

P n Bridleways are generally unsurfaced routes open to MORE CYCLE RIDES Cuckmere Haven and Friston Forest A very easy short concrete path runs from the car park by the A259 at Exceat CYCLE cyclists and horse riders. P BARCOMBE (in the SE corner of this map) to the sea at Cuckmere Haven. They are usually marked with PLUMPTON GREEN P 2 National Cycle Route 2 Brighton and Berwick (and beyond), More challenging is the network of hilly forest tracks through blue arrow waymark posts. 2 along roads and cycle path, with some busier roads around PLUMPTON Sta. 1 Friston Forest. LEWES 2 Newhaven. Runs below the cliffs between Brighton and Footpaths (paths shown on PLUMPTON BARCOMBE MILLS Kingston See town map for this short, level surfaced route n DITCHLING RACE COURSE 1 Saltdean signposted around back roads in Peacehaven, cross - the map with short dashes) HASSOCKS south from Lewes to Kingston; can extend to South Downs Local cycling MUSEUM STREAT P Tra 2 ing the A259 and dropping into Newhaven; section along main 1 1 ins A Way. are open to walkers only. to 2 OF ART + L 7 road (or push along pavement) past a retail park and Sains - information KEYMER DITCHLING EAST CHlLTINGTON o 5 3 Lewes to Falmer alongside A27 Not a pretty ride, but useful Cycling on footpaths is not CRAFT nd bury’s, then on parallel cycle path to Bishopstone, with optional P on for getting to the universities at Falmer, and to Brighton. allowed without the owner's P 1 diversion into Ouse Valley Nature Reserve; continues along North of Barcombe Excellent and very scenic cycling on CYCLING permission and there may be Cuckmere Valley past Alfriston and Berwick station.