Looking Again at Vanessa Bell's View Into a Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Is Time for Virginia Woolf

TREBALL DE FI DE GRAU Tutor/a: Dra. Ana Moya Gutierrez Grau de: Estudis Anglesos IT IS TIME FOR VIRGINIA WOOLF Ane Iñigo Barricarte Universitat de Barcelona Curso 2018/2019, G2 Barclona, 11 June 2019 ABSTRACT This paper explores the issue of time in two of Virginia Woolf’s novels; Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. The study will not only consider how the theme is presented in the novels but also in their filmic adaptations, including The Hours, a novel written by Michael Cunningham and film directed by Stephen Daldry. Time covers several different dimensions visible in both novels; physical, mental, historical, biological, etc., which will be more or less relevant in each of the novels and which, simultaneously, serve as a central point to many other themes such as gender, identity or death, among others. The aim of this paper, beyond the exploration of these dimensions and the connection with other themes, is to come to a general and comparative conclusion about time in Virginia Woolf. Key Words: Virginia Woolf, time, adaptations, subjective, objective. Este trabajo consiste en una exploración del tema del tiempo en dos de las novelas de Virginia Woolf; La Señora Dalloway y Al Faro. Dicho estudio, no solo tendrá en cuenta como se presenta el tema en las novelas, sino también en la adaptación cinematográfica de cada una de ellas, teniendo también en cuenta Las Horas, novela escrita por Michael Cunningham y película dirigida por Stephen Daldry. El tiempo posee diversas dimensiones visibles en ambos trabajos; física, mental, histórica, biológica, etc., que cobrarán mayor o menor importancia en cada una de las novelas y que, a su vez, sirven de puntos de unión para otros muchos temas como pueden ser el género, la identidad o la muerte entre otros. -

Angelica Garnett, Ou Le Difficile Héritage De Bloomsbury, Florence Noiville, Le Monde, 8 Juin 2001 a Forcalquier, on L'appelle « L'anglaise »

Angelica Garnett, ou le difficile héritage de Bloomsbury, Florence Noiville, Le Monde, 8 juin 2001 A Forcalquier, on l'appelle « l'Anglaise ». Pour la trouver, il faut gravir des rues aux noms fanés – rue Mercière, rue Violette –, continuer vers la citadelle, marcher en direction d'une chapelle romane à demi enfouie sous les coquelicots et les orties, jusqu'à ce que surgisse enfin une maison basse contemplant tranquillement la chaîne du Lubéron. Une maison qui sent la peinture et l'essence de térébenthine. Il y a des couleurs, des craies partout, des huiles fines de chez Sennelier, des fusains épars, des pots de vernis « bistrot » et de fixatif, des pinceaux en bataille sur un exemplaire du TLS... « Excusez-moi, je dois emballer ce dessin. C'est pour une exposition que je fais à Londres. » Elle lève les yeux vers vous, deux grands yeux bleus très pâles : c'est alors qu'on la reconnaît... « l'Anglaise ». Ce que l'on voit à cet instant, c'est cette fameuse photo de Virginia Woolf par Gisèle Freund : la transparence, la mélancolie du regard, l'ovale si bien dessiné du visage. Fille de l'artiste Vanessa Bell, l'aînée de la famille Stephen, et du peintre Duncan Grant, Angelica Garnett est la nièce de Virginia Woolf. A 82 ans, elle vit en Provence depuis 1984 : « Je connaissais bien la France, j'avais déjà eu une maison dans le Lot et j'avais toujours voulu y vivre. Je voulais aussi me séparer de Charleston qui me prenait trop et m'empêchait de peindre. Je voulais échapper à ça, échapper à tout, aux Anglais aussi. -

1 NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 in Memoriam

Virginia Woolf Miscellany NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 Centennial Contemplations on Early Work (16) while Rosie Reynolds examines the numerous by Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf o o o o references to aunts in The Voyage Out and examines You can access issues of the the narrative function of Rachel’s aunt, Helen To observe the centennial of Virginia Woolf’s Virginia Woolf Miscellany Ambrose, exploring Helen’s perspective as well as early works, The Voyage Out, and Night and online on WordPress at the identity and self-revelation associated with the Day, and also Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the https://virginiawoolfmiscellany. emerging relationship between Rachel and fellow Jungle. I invited readers to adopt Nobel Laureate wordpress.com/ tourist Terence. Daniel Kahneman’s approach to problem-solving and decision making. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Virginia Woolf Miscellany: In her essay, Mine Özyurt Kılıç responds directly Kahneman distinguishes between fast thinking— Editorial Board and the Editors to the call with a “slow” reading of the production typically intuitive, impressionistic and reliant on See page 2 process that characterizes the work of Hogarth Press, associative memory—and the more deliberate, Editorial Policies particularly in contrast to the mechanized systems precise, detailed, and logical process he calls slow See page 6 from which it was distinguished. She draws upon “A thinking. Fast thinking is intuitive, impressionistic, y Mark on the Wall,” “Kew Gardens,” and “Modern and dependent upon associative memory. Slow – TABLE OF CONTENTS – Fiction,” to develop the notion and explore the thinking is deliberate, precise, detailed, and logical. -

The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2019 In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group Christina A. Barber IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Barber, Christina A., "In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group" (2019). Academic Research and Dissertations. 29. https://digitalmaine.com/academic/29 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE MOUTH OF THE WOOLF: THE POSTHUMANISTIC THEATER OF THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP Christina Anne Barber Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy August, 2019 ii Accepted by the faculty at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Simonetta Moro, PhD Director of School & Vice President for Academic Affairs Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: George Smith, PhD Founder & President Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: Conny Bogaard, PhD Executive Director Western Kansas Community Foundation iii © 2019 Christina Anne Barber ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv Mother of Romans, joy of gods and men, Venus, life-giver, who under planet and star visits the ship-clad sea, the grain-clothed land always, for through you all that’s born and breathes is gotten, created, brought forth to see the sun, Lady, the storms and clouds of heaven shun you, You and your advent; Earth, sweet magic-maker, sends up her flowers for you, broad Ocean smiles, and peace glows in the light that fills the sky. -

Virginia Woolf and the Tools of Visual Literacy. Janice M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 The Thousand Appliances: Virginia Woolf and the Tools of Visual Literacy. Janice M. Stein Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Stein, Janice M., "The Thousand Appliances: Virginia Woolf and the Tools of Visual Literacy." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5906. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5906 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced frommicrofilm the master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough,margins, substandard and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

November 2-5 2017

LITERARY FESTIVAL NOVEMBER 2-5 2017 An International Festival Celebrating Literature, Ideas and Creativity. CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM FOR TICKETS VISIT CHARLESTONTOCHARLESTON.COM CALL 843.723.9912 1 WELCOME Welcome to an exciting new trans-Atlantic literary festival hosted by two remarkable sites named Charleston. The partnership between two locations with the same name, separated by a vast oceanic expanse, is no mere coincidence. Through the past several centuries, both Charleston, SC and Charleston, Sussex have been home to extraordinary scholars, authors and artists. A collaborative literary festival is a natural and timely expression of their shared legacies. UK © C Luke Charleston, Established in 1748, the Charleston Library Society is the oldest cultural institution in the South and the country’s second oldest circulating library. Boasting four signers of the Declaration of Independence and hosting recent presentations by internationally acclaimed scholars such as David McCullough, Jon Meacham, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, its collections and programs reflect the history of intellectual curiosity in America. The Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, England was home to the A Hesslenberg Charleston © Festival famed Bloomsbury group - influential, forward-looking artists, writers, and thinkers, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and frequent guests Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot. For almost thirty years, Charleston has offered one of the most well-respected literary festivals in Europe, where innovation and inspiration thrive. This year’s Charleston to Charleston Literary Festival inaugurates a partnership dedicated to literature, ideas, and creativity. With venues as historic as the society itself, the new festival will share Charleston’s famed Southern hospitality while offering vibrant insights from contemporary speakers from around the globe. -

Berwick Church and the Bloomsbury Murals

Berwick Church and the Bloomsbury Murals: Writing and Research by Students from the University of Sussex Spring 2020 Preface Hope Wolf Berwick and Beyond: Bee Hendry Abstract Forms and International References in Duncan Grant’s Designs for the Church Murals Heartfelt Summer Rupert Tarrant Country and City: Charise Niarchos Mrs Sandilands and the Making of the Berwick Murals A ‘space for us’: Scarlett May Walker Local Communities and their Heritage ‘Be content with the view in front of us’: Grace van der Byl Williams An Installation Designed for St Michael and All Angels Church Preface Hope Wolf This pamphlet was made by third-year students from the School of English at the University of Sussex. They took part in a course called ‘Arts and Community’, the aim of which is to work with cultural organisations in order to bring undergraduate research to an audience outside of the university. The course focuses on a different place and project each year it runs, and in the spring of 2020 students engaged with an initiative, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, to conserve the Berwick Church murals. They sought to tell new stories about murals and the Berwick site using archival documents at the Keep (East Sussex Record Office), drafts of the murals at both Charleston and the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne, oral history interviews gathered as part of the HLF project, writing from the fields of literature, art history and geography, and on-site observations of the church and its environs (we walked from Berwick to Charleston Farmhouse via Alciston). The course was linked to the Centre for Modernist Studies research project on Sussex Modernism, and connections were made between other cultural sites in the area, both on and off the map. -

Curriculum Vitae

CV/September 2017 1 Curriculum Vitae SUZANNE RAITT Office address: College of William & Mary Department of English PO Box 8795 Williamsburg Virginia 23187-8795 Office phone: 757-221-1832 Cell phone: 202-262-7356 Fax: 757-221-1844 E-mail: [email protected] Home address: 1820 Ontario Place NW Washington, DC 20009 Home phone: 202-483-1604 Academic Qualifications 1985-1988 Jesus College, University of Cambridge, England PhD, English (awarded May 1989) Thesis title: The Texture of a Friendship: V.Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf 1983-85 Yale University MA, English 1980-83 Jesus College, University of Cambridge, England BA Hons., English Part I: First Class Part II: First Class Academic and Administrative Appointments 2016-19 Chair, English Department, College of William and Mary 2015-present Chancellor Professor of English 2014-16 Faculty Representative on the Board of Visitors, College of William and Mary 2011-14 Secretary; then Vice-President; then President of Faculty Assembly, College of William and Mary 2004-2008 Director, Women’s Studies Program, College of William and Mary 2002-2005 Margaret L. Hamilton Professor of English, College of William and Mary [term professorship] 2000-present Professor with tenure, Department of English, College of William and Mary 1995-2000 Associate Professor with tenure, Department of English Language and Literature/Program in Women’s Studies, University of Michigan CV/September 2017 2 1989-1995 Lecturer [Assistant Professor with tenure] and then Senior Lecturer [Associate Professor] in English, Queen Mary -

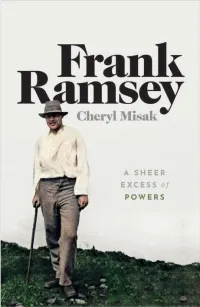

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Virginia Woolf Miscellany, Issue 62, Spring 2003

NUMBER 62 SPRING 2003 Letter to the Readers: Reader” as well as reviews of books by Jessica Berman, Donald J. Childs, Katherine Dalsimer, and David Ellison. “Never has there been such a time. Last week end we were at Charleston and very gloomy. Gloom increased on Monday. In London it was hectic and gloomy and at the same time This issue of the Virginia Woolf Miscellany represents a new phase in the history of despairing and yet cynical and calm. The streets were crowded. People were everywhere talking this publication. The Miscellany has moved across the country from sunny Sonoma loudly about war. There were heaps of sandbags in the streets, also men digging trenches, lorries to snowy New Haven, from a California State University to a Connecticut State delivering planks, loud speakers slowly driving and solemnly exhorting the citizens of Westminster Go and fit your gas masks. There was a long queue of people waiting outside the Mary Ward University. After nearly 30 years of publishing this small but vital periodical, J.J. settlement to be fitted. [W]e sat and discussed the inevitable end of civilization. [Kingsley Wilson has handed the torch to a new editorial board. The publication itself has a Martin] said the war would last our life time[.] . Anyhow, Hitler meant to bombard London, new future as a soon-to-be subscription periodical with a web presence. Members of probably with no warning; the plan was to drop bombs on London with twenty minute intervals the International Virginia Woolf Society will continue to receive the Miscellany as a for forty eight hours. -

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches the First Leg of The

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches The first leg of the legendary 18-miler ended with Shetland ponies in the village of Firle. The waist-high animals were unendingly friendly in their welcome, ambling over from their grazing spots to willingly be petted. Needless to say, they were an instant hit. “Can we ride them?” I had half-jokingly asked when first told that we would be encountering these cute-tastic creatures. My question had been met with chuckling doubt as to the animals’ ability to hold us, but there is an even more compelling reason not to saddle up one of these little beasts. Shetland folklore, naturally obligated to make mention of the distinctive animals, brings us the njuggle. A folkloric waterhorse inclined to potentially malevolent pranks, the njuggle is a nuisance primarily to millers in its harmlessly playful incarnation, hiding under the mill and interfering with its operation but easily banished with a lump of burning peat. Its more sinister side resembles its Celtic analog, the kelpie. In the form of a splendid Shetland pony, the njuggle wanders about until some unwary weary traveler, perhaps lured by the ill-intent of the creature or perhaps just by unlucky circumstance, mounts its back. With this, the njuggle gallops headlong into the nearest loch, often drowning the hapless traveler who ought to have known better than to accept a ride from a Shetland pony. There were no lochs nearby, only the river Ouse. Either way, it was a less fanciful instinct that kept me off the ponies’ backs; but their deep eyes and calm acquiescence to human overtures of friendship seemed to me a perfect lure. -

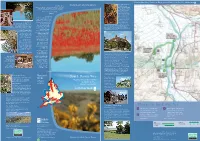

Things to Look Out

NATIONAL TRAIL © Property of The Charleston Trust Exploring Bloomsbury Country; the Downs between Rodmell and Berwick Wander the Wide Green Downs Green Wide the Wander The Bloomsbury by the same route. route. same the by meadows to Virginia Woolf’s House at Rodmell. It returns It Rodmell. at House Woolf’s Virginia to meadows Group of artists, Ouse, then follows the riverbank and across the flood the across and riverbank the follows then Ouse, writers, and intellectuals From Southease station this route crosses the River the crosses route this station Southease From included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, About 4 miles (6 km), 2 hours 2 km), (6 miles 4 About EM Forster, Duncan A Stroll Stroll A Grant, Lytton Strachey, and the economist John come prepared! prepared! come Maynard-Keynes who especially in rain or low cloud, so cloud, low or rain in especially lived at Tilton. Many of exposed in cold windy weather, windy cold in exposed the Bloomsbury Group of the Downs can be surprisingly be can Downs the of Firle if preferred. if Firle formed a small and appropriate footwear. The tops The footwear. appropriate Station. There is a short cut back to back cut short a is There Station. unique community in can be muddy, so wear so muddy, be can South Downs Way back to Southease to back Way Downs South the Rodmell/Firle area winter parts of all the walks the all of parts winter Downs to Bopeep then follows the follows then Bopeep to Downs between the two world wars - ironically they became longer walks.