Ids Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Paper 104 July 2018

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 104 July 2018 Food Security Policy Project (FSPP) MYANMAR’S RURAL ECONOMY: A CASE STUDY IN DELAYED TRANSFORMATION By Duncan Boughton, Nilar Aung, Ben Belton, Mateusz Filipski, David Mather, and Ellen Payongayong Food Security Policy Research Papers This Research Paper series is designed to timely disseminate research and policy analytical outputs generated by the USAID funded Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP) and its Associate Awards. The FSP project is managed by the Food Security Group (FSG) of the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU), and implemented in partnership with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Together, the MSU-IFPRI-UP consortium works with governments, researchers, and private sector stakeholders in Feed the Future focus countries in Africa and Asia to increase agricultural productivity, improve dietary diversity, and build greater resilience to challenges like climate change that affect livelihoods. The papers are aimed at researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, educators, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Portuguese, or other languages. Copies of all FSP Research Papers and Policy Briefs are freely downloadable in pdf format from the following Web site: www.foodsecuritypolicy.msu.edu. Copies of all FSP papers and briefs are also submitted to the USAID Development Experience Clearing House (DEC) at: http://dec.usaid.gov/ ii AUTHORS Duncan Boughton is Professor, Ben Belton is Assistant Professor, David Mather is Assistant Professor, and Ellen Payongayong is Specialist, all with International Development, in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU); Nilar Aung is a Consultant with AFRE at MSU; and Mateusz Filipski is Research Fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute. -

The Impact of the Exchange Rate Unification on Trade Balance in Myanmar

THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 Professor Jong-Il YOU THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Jong-Il YOU, Supervisor Professor Chrysostomos TABAKIS Professor Jin Soo LEE Approval as of December, 2016 ABSTRACT This study analyzes the impacts of the exchange rate unification on the trade balance in Myanmar based on Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Model. This paper’s main objective is to determine whether the exchange rate has positive or negative effects on the trade balance. This study has discovered that the exchange rate unification has a positive effect on the trade balance in the long run. Additionally, this study finds that Exchange Rate and Foreign Direct Investment have positive effects on the trade balance while GDP growth rate and Inflation has negative impact in the long run. As a policy implication, this study suggests that the government should focus on economic stability and effective monetary policies within the country. -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

State Fragility in Myanmar: Fostering Development in the Face of Protracted Conflict

AUGUST 2018 State fragility in Myanmar: Fostering development in the face of protracted conflict Renaud Egreteau Cormac Mangan Renaud Egreteau is Associate Professor in the Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong. Cormac Mangan is a former Country Economist for IGC Myanmar. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to this report: Ian Porter, Nan Sandi, Paul Minoletti, Gerard McCarthy, and Andrew Bauer. Acronyms ASEAN: Association of South East Asian Nations BSPP: Burma Socialist Program Party CPB: Communist Party of Burma FDI: Foreign direct investment GAD: General Administration Department IDPs: Internally displaced people MEC: Myanmar Economic Corporation NLD: National League for Democracy NCA: Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement SMEs: Small and medium enterprises SLORC: State Law and Order Restoration Council SOEs: State-owned enterprises SPDC: State Peace and Development Council UMEHL: Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited USDP: Union Solidarity and Development Party About the commission The LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development was launched in March 2017 to guide policy to address state fragility. The commission, established under the auspices of the International Growth Centre, is sponsored by LSE and University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. It is funded from the LSE KEI Fund and the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Front page photo: Street -

MYANMAR 2014 Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity in a Time of Transition

Report No. 93050-MM NOVEMBER, MYANMAR 2014 Ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity in a time of transition Photo by: Ni Ni Myint/World Bank, 2014 A SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC World Bank Office Yangon No.57, Pyay Road (Corner of Shwe Hinthar Road) 61/2 Mile, Hlaing Township, Yangon Republic of the Union of Myanmar +95 (1) 654824 www.worldbank.org/myanmar www.facebook.com/WorldBankMyanmar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a World Bank Group team from the World Bank – IDA, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) led by Khwima Nthara (Program Leader & Lead Economist) under the direct supervision of Mathew Verghis (Practice Manager, MFM) and Shubham Chaudhuri (Practice Manager, MFM & Poverty). Cath- erine Martin (Principal Strategy Officer) was the IFC’s Task Manag- er. Overall guidance was provided by Ulrich Zachau (Country Direc- tor), Abdoulaye Seck (Country Manager), Kanthan Shankar (Former Country Manager), Sudhir Shetty (Regional Chief Economist), Betty Hoffman (Former Regional Chief Economist), Constantinee Chikosi (Portfolio and Operations Manager), Julia Fraser (Practice Manag- er), Jehan Arulpragasam (Practice Manager), Hoon Sahib Soh (Op- erations Adviser), Rocio Castro (VP Adviser), Antonella Bassani (Strategy and Operations Director), Antony Gaeta (Country Program Coordinator), Maria Ionata (Former Country Program Coordinator),- Vikram Kumar (IFC Resident Representative), and Simon Andrews (Senior Manager). The report drew from thematic input notes prepared by a cross-sec- tion of Bank staff as follows: -

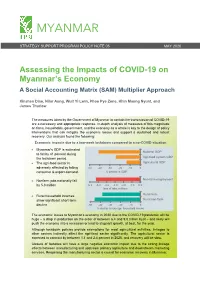

Assessing the Impacts of COVID 19 on Myanmar's Economy

MYANMAR STRATEGY SUPPORT PROGRAM POLICY NOTE 05 MAY 2020 Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19 on Myanmar’s Economy A Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) Multiplier Approach Xinshen Diao, Nilar Aung, Wuit Yi Lwin, Phoo Pye Zone, Khin Maung Nyunt, and James Thurlow The measures taken by the Government of Myanmar to contain the transmission of COVID-19 are a necessary and appropriate response. In-depth analysis of measures of this magnitude on firms, households, government, and the economy as a whole is key to the design of policy interventions that can mitigate the economic losses and support a sustained and robust recovery. Our analysis found the following: Economic impacts due to a two-week lockdown compared to a no-COVID situation • Myanmar’s GDP is estimated National GDP to fall by 41 percent during the lockdown period. Agri-food system GDP • The agri-food sector is Agricultural GDP adversely affected by falling -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 consumer & export demand. % decline in GDP Non-farm employment • Nonfarm jobs nationally fall by 5.3 million -6.0 -5.0 -4.0 -3.0 -2.0 -1.0 0.0 loss of jobs, millions Rural farm • Rural household incomes show significant short-term Rural non-farm decline -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 % decline in average household income The economic losses to Myanmar’s economy in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic will be huge – a drop in production on the order of between 6.4 and 9.0 trillion Kyat – and likely will push the economy into a recession or lead to stagnant growth, at best, for the year. -

The Role of the Military in Myanmar's Political Economy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2016-03 The role of the military in Myanmar's political economy Stein, Pamela T. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/48478 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE ROLE OF THE MILITARY IN MYANMAR’S POLITICAL ECONOMY by Pamela T. Stein March 2016 Thesis Advisor: Naazneen Barma Second Reader: Zachary Shore Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) March 2016 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE ROLE OF THE MILITARY IN MYANMAR’S POLITICAL ECONOMY 6. AUTHOR(S) Pamela T. Stein 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

Exposing the Geopolitics of Myanmar's Borderlands with Critical Remote Sensing

remote sensing Article Uneven Frontiers: Exposing the Geopolitics of Myanmar’s Borderlands with Critical Remote Sensing Mia M. Bennett 1,* and Hilary Oliva Faxon 2 1 Department of Geography, Room 10.23, Jockey Club Tower, Centennial Campus, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 999077, China 2 Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, 130 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94709, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A critical remote sensing approach illuminates the geopolitics of development within Myanmar and across its ethnic minority borderlands. By integrating nighttime light (NTL) data from 1992–2020, long-term ethnographic fieldwork, and a review of scholarly and gray literature, we analyzed how Myanmar’s economic geography defies official policy, attesting to persistent inequality and the complex relationships between state-sponsored and militia-led violence, resource extraction, and trade. While analysis of DMSP-OLS data (1992–2013) and VIIRS data (2013–2020) reveals that Myanmar brightened overall, especially since the 2010s in line with its now-halting liberalization, growth in lights was unequally distributed. Although ethnic minority states brightened more rapidly than urbanized ethnic majority lowland regions, in 2020, the latter still emitted 5.6-fold more radiance per km2. Moreover, between 2013 and 2020, Myanmar’s borderlands were on average just 13% as bright as those of its five neighboring countries. Hot spot analysis of radiance within a 50 km-wide area spanning both sides of the border confirmed that most significant clusters of light lay outside Myanmar. Among the few hot spots on Myanmar’s side, many were associated Citation: Bennett, M.M.; Faxon, H.O. -

Political Turmoil, Leadership Fiasco and Economic Fallout of Myanmar Crisis in 2021

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 30 Volume 4, Issue 3, March 2021 https://www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 Political Turmoil, Leadership Fiasco and Economic Fallout of Myanmar Crisis in 2021 Subhendu Bhattacharya1*, Sona Raghuvanshil2 1,2Amity Global Business School, Mumbai, India Abstract: Myanmar caught in political turmoil at the outset of disintegration of incumbent AFPFL party. First significant February 2021. Military seized control in a coup and overthrew military coup happened in 1962 when Gen Ne Win dismantled elected government. Tension gripped the nation and uncertainty federal structure and initiated Burmese pattern of socialism. brought the lives of people on edge. Ruling party National League for Democracy (NLD) won general election with landslide victory Single party rule was established to reinforce socialism drive held in November 2020. Eminent leader and NLD figurehead and it succeeded in nationalisation of economy. Military power Aung San Suu Kyi re-established her popularity. It would have brought an end of independence of press. Military leaders been democratic rule with elected leader in her second term. The brought new constitution into effect in 1974 which strengthened election was significant to assess credibility of Aung San Suu Kyi armed forced and military rule unprecedentedly. Law was who faced criticism worldwide for her inaction during Rohingya enforced in 1982 to eliminate non- indigenous associate citizen crisis. Opposition party supported by military brought allegation of voting fraud and urged about rerun of election. Opposition from holding public office. pointed out government irregulates in election process and denied Economic crisis gripped the nation in 1987 which led to its outcome. -

Myanmar: a Political Economy Analysis

Myanmar: A Political Economy Analysis Kristian Stokke, Roman Vakulchuk, Indra Øverland Report commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2018 ISSN: 1894-650X The report has been commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views, official policy or position of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be printed in part or in full without the permission of the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Myanmar: A Political Economy Analysis Kristian Stokke, Roman Vakulchuk, Indra Øverland Report commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2018 Contents Map of Myanmar .................................................................................................................. VI About the report .................................................................................................................. VII Authors ................................................................................................................................. VIII List of acronyms .................................................................................................................. -

Investment Coalitions and Public Support: a Survey Experimental Approach to Chinese Investment in Myanmar1

Global Development Policy Center GCI WORKING PAPER 004 • 11/2018 GLOBAL CHINA INITIATIVE Investment Coalitions and Public Support: A Survey Experimental Approach to Chinese Investment in Myanmar1 YOUYI ZHANG & YING YAO ABSTRACT While under military rule before 2011, the presence and activities of multinational corporations (MNCs) in Myanmar were infrequently mentioned by the media and largely obscured from public attention. However, since 2011, FDI has become one of the most salient and hotly debated issues in the context of Myanmar’s rapidly changing political economy. Existing anecdotal evidence and Youyi Zhang, Cornell case studies offer only a partial view of Chinese FDI and systematic data on public attitudes towards University Government different types of Chinese FDI is lacking. To build a more nuanced understanding, we conducted a Department & Boston University survey experiment on public perceptions of Chinese FDI in Myanmar composed of data from 956 Global Development Policy respondents and another experiment with about 2000 college students across the country. The key Center. factors under examination are types of Chinese firms’ local partners and their social engagement strategies. We asked the respondents to read fabricated news with multiple scenarios of varying types of investment and subsequently react to our questionnaire. We found that public perceptions of Chinese projects are contingent on a firm’s selection of local partner and social engagement strategy. Respondents react more favorably to projects that partner with local private companies and engage with local communities directly. With the newly initiated China- Myanmar Economic Corridor under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, this research informs stakeholders in China and Myanmar on how to better manage Chinese FDI in Myanmar. -

Hkakabo Razi Landscape As One of the Last Exemplar of Large Contiguous Forests Marcela Suarez‑Rubio 1*, Grant Connette 2, Thein Aung3, Myint Kyaw 4 & Swen C

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Hkakabo Razi landscape as one of the last exemplar of large contiguous forests Marcela Suarez‑Rubio 1*, Grant Connette 2, Thein Aung3, Myint Kyaw 4 & Swen C. Renner 5 Deforestation and forest degradation around the world endanger the functioning of ecosystems, climate stability, and conservation of biodiversity. We assessed the spatial and temporal dynamics of forest cover in Myanmar’s Hkakabo Razi Landscape (HRL) to determine its integrity based on forest change and fragmentation patterns from 1989 to 2016. Over 80% of the HRL was covered by natural areas, from which forest was the most prevalent (around 60%). Between 1989 and 2016, forest cover declined at an annual rate of 0.225%. Forest degradation occurred mainly around the larger plains of Putao and Naung Mung, areas with relatively high human activity. Although the rate of forest interior loss was approximately 2 to 3 times larger than the rate of total forest loss, forest interior was prevalent with little fragmentation. Physical and environmental variables were the main predictors of either remaining in the current land‑cover class or transitioning to another class, although remaining in the current land cover was more likely than land conversion. The forests of the HRL have experienced low human impact and still constitute large tracts of contiguous forest interior. To ensure the protection of these large tracts of forest, sustainable forest policies and management should be implemented. Despite human practices and the unprecedented use of natural resources, forests are still widely distributed globally and cover around 30% of the Earth’s surface 1,2.