Using Natural Resources for New Federalism and Unity July 2013 Page 3 of 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China-Myanmar Relations: [email protected] New Challenges Unfolding (Wednesday Seminar, ICS, New Delhi, April 19, 2017) Objectives

Sampa Kundu Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses New Delhi China-Myanmar Relations: [email protected] New Challenges Unfolding (Wednesday Seminar, ICS, New Delhi, April 19, 2017) Objectives the challenging factors of Sino-Myanmar bilateral relations; especially the recent ones as Understanding they are unfolding through the controversial Chinese projects in Myanmar the role of the emerging domestic socio-ethno-political scenario in Myanmar in deciding the Explaining trajectory of Sino-Myanmar bilateral relations. Offering a Myanmar-centric perspective to understand the Sino-Myanmar bilateral relations Situating Myanmar in Chinese Global dream projects • From 1988, in the wake of Myanmar’s isolation from rest of the world, China and Myanmar came closer to each other • Myanmar became heavily dependant on Pauk Phaw between Chinese money and China became its friend and mentor; defence and security China and Myanmar partnership too enhanced to a large extent • Myanmar never shied away from saying that irrespective of the forms of government, Myanmar and China will continue to be each other’s Pauk Phaw. Flows of FDI into Myanmar (values in Region/Economy 2001 2005 2010 2012 USD Million) World 19 6,066 19,999 1,419 East Asia 10 1 16,744 526 China 3 1 8,269 407 Southeast Asia 3 6,034 2,449 584 India - 31 - 12 Source: UNCTAD Market Trade (USD Million) % Share in Total Myanmar’s Top Five Export Trade Export Partners, 2010 Thailand 3,177 41.67 Hong Kong 1,612 21.14 India 958 12.56 China 476 6.25 Singapore 276 3.62 Source: World Integrated -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Research Paper 104 July 2018

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 104 July 2018 Food Security Policy Project (FSPP) MYANMAR’S RURAL ECONOMY: A CASE STUDY IN DELAYED TRANSFORMATION By Duncan Boughton, Nilar Aung, Ben Belton, Mateusz Filipski, David Mather, and Ellen Payongayong Food Security Policy Research Papers This Research Paper series is designed to timely disseminate research and policy analytical outputs generated by the USAID funded Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP) and its Associate Awards. The FSP project is managed by the Food Security Group (FSG) of the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU), and implemented in partnership with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Together, the MSU-IFPRI-UP consortium works with governments, researchers, and private sector stakeholders in Feed the Future focus countries in Africa and Asia to increase agricultural productivity, improve dietary diversity, and build greater resilience to challenges like climate change that affect livelihoods. The papers are aimed at researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, educators, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Portuguese, or other languages. Copies of all FSP Research Papers and Policy Briefs are freely downloadable in pdf format from the following Web site: www.foodsecuritypolicy.msu.edu. Copies of all FSP papers and briefs are also submitted to the USAID Development Experience Clearing House (DEC) at: http://dec.usaid.gov/ ii AUTHORS Duncan Boughton is Professor, Ben Belton is Assistant Professor, David Mather is Assistant Professor, and Ellen Payongayong is Specialist, all with International Development, in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU); Nilar Aung is a Consultant with AFRE at MSU; and Mateusz Filipski is Research Fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute. -

The Impact of the Exchange Rate Unification on Trade Balance in Myanmar

THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 Professor Jong-Il YOU THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Jong-Il YOU, Supervisor Professor Chrysostomos TABAKIS Professor Jin Soo LEE Approval as of December, 2016 ABSTRACT This study analyzes the impacts of the exchange rate unification on the trade balance in Myanmar based on Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Model. This paper’s main objective is to determine whether the exchange rate has positive or negative effects on the trade balance. This study has discovered that the exchange rate unification has a positive effect on the trade balance in the long run. Additionally, this study finds that Exchange Rate and Foreign Direct Investment have positive effects on the trade balance while GDP growth rate and Inflation has negative impact in the long run. As a policy implication, this study suggests that the government should focus on economic stability and effective monetary policies within the country. -

Ids Working Paper

IDS WORKING PAPER Volume 2018 No 513 Energy Protests in Fragile Settings: The Unruly Politics of Provisions in Egypt, Myanmar, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe, 2007 –2017 Naomi Hossain with Fatai Aremu, Andy Buschmann, Egidio Chaimite, Simbarashe Gukurume, Umair Javed, Edson da Luz (aka Azagaia), Ayobami Ojebode, Marjoke Oosterom, Olivia Marston, Alex Shankland, Mariz Tadros, and Kátia Taela June 2018 Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research Programme In a world shaped by rapid change, the Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research programme focuses on fragile, conflict and violence affected settings to ask how social and political action for empowerment and accountability emerges in these contexts, what pathways it takes, and what impacts it has. A4EA is implemented by a consortium consisting of: the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), the Accountability Research Center (ARC), the Collective for Social Science Research (CSSR), the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS), Itad, Oxfam GB, and the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). Research focuses on five countries: Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, and Pakistan. A4EA is funded by UK aid from the UK government. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of our funder. Energy Protests in Fragile Settings: The Unruly Politics of Provisions in Egypt, Myanmar, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe, 2007–2017 Naomi Hossain with Fatai Aremu, Andy Buschmann, Egidio Chaimite, Simbarashe Gukurume, Umair Javed, Edson da Luz (aka Azagaia), Ayobami Ojebode, Marjoke Oosterom, Olivia Marston, Alex Shankland, Mariz Tadros, and Kátia Taela IDS Working Paper 513 © Institute of Development Studies 2018 ISSN: 2040-0209 ISBN: 978-1-78118-449-3 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar

Policy Studies 71 Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar Matthew J. Walton and Susan Hayward Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar About the East-West Center The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for infor- mation and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US main- land and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organization with funding from the US government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and govern- ments in the region. Policy Studies an East-West Center series Series Editors Dieter Ernst and Marcus Mietzner Description Policy Studies presents original research on pressing economic and political policy challenges for governments and industry across Asia, About the East-West Center and for the region's relations with the United States. Written for the The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding policy and business communities, academics, journalists, and the in- among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the formed public, the peer-reviewed publications in this series provide Pacifi c through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. -

State Fragility in Myanmar: Fostering Development in the Face of Protracted Conflict

AUGUST 2018 State fragility in Myanmar: Fostering development in the face of protracted conflict Renaud Egreteau Cormac Mangan Renaud Egreteau is Associate Professor in the Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong. Cormac Mangan is a former Country Economist for IGC Myanmar. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to this report: Ian Porter, Nan Sandi, Paul Minoletti, Gerard McCarthy, and Andrew Bauer. Acronyms ASEAN: Association of South East Asian Nations BSPP: Burma Socialist Program Party CPB: Communist Party of Burma FDI: Foreign direct investment GAD: General Administration Department IDPs: Internally displaced people MEC: Myanmar Economic Corporation NLD: National League for Democracy NCA: Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement SMEs: Small and medium enterprises SLORC: State Law and Order Restoration Council SOEs: State-owned enterprises SPDC: State Peace and Development Council UMEHL: Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited USDP: Union Solidarity and Development Party About the commission The LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development was launched in March 2017 to guide policy to address state fragility. The commission, established under the auspices of the International Growth Centre, is sponsored by LSE and University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. It is funded from the LSE KEI Fund and the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Front page photo: Street -

MYANMAR 2014 Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity in a Time of Transition

Report No. 93050-MM NOVEMBER, MYANMAR 2014 Ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity in a time of transition Photo by: Ni Ni Myint/World Bank, 2014 A SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC World Bank Office Yangon No.57, Pyay Road (Corner of Shwe Hinthar Road) 61/2 Mile, Hlaing Township, Yangon Republic of the Union of Myanmar +95 (1) 654824 www.worldbank.org/myanmar www.facebook.com/WorldBankMyanmar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a World Bank Group team from the World Bank – IDA, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) led by Khwima Nthara (Program Leader & Lead Economist) under the direct supervision of Mathew Verghis (Practice Manager, MFM) and Shubham Chaudhuri (Practice Manager, MFM & Poverty). Cath- erine Martin (Principal Strategy Officer) was the IFC’s Task Manag- er. Overall guidance was provided by Ulrich Zachau (Country Direc- tor), Abdoulaye Seck (Country Manager), Kanthan Shankar (Former Country Manager), Sudhir Shetty (Regional Chief Economist), Betty Hoffman (Former Regional Chief Economist), Constantinee Chikosi (Portfolio and Operations Manager), Julia Fraser (Practice Manag- er), Jehan Arulpragasam (Practice Manager), Hoon Sahib Soh (Op- erations Adviser), Rocio Castro (VP Adviser), Antonella Bassani (Strategy and Operations Director), Antony Gaeta (Country Program Coordinator), Maria Ionata (Former Country Program Coordinator),- Vikram Kumar (IFC Resident Representative), and Simon Andrews (Senior Manager). The report drew from thematic input notes prepared by a cross-sec- tion of Bank staff as follows: -

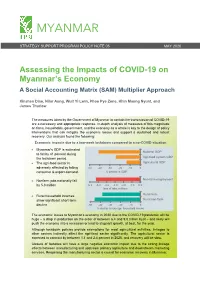

Assessing the Impacts of COVID 19 on Myanmar's Economy

MYANMAR STRATEGY SUPPORT PROGRAM POLICY NOTE 05 MAY 2020 Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19 on Myanmar’s Economy A Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) Multiplier Approach Xinshen Diao, Nilar Aung, Wuit Yi Lwin, Phoo Pye Zone, Khin Maung Nyunt, and James Thurlow The measures taken by the Government of Myanmar to contain the transmission of COVID-19 are a necessary and appropriate response. In-depth analysis of measures of this magnitude on firms, households, government, and the economy as a whole is key to the design of policy interventions that can mitigate the economic losses and support a sustained and robust recovery. Our analysis found the following: Economic impacts due to a two-week lockdown compared to a no-COVID situation • Myanmar’s GDP is estimated National GDP to fall by 41 percent during the lockdown period. Agri-food system GDP • The agri-food sector is Agricultural GDP adversely affected by falling -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 consumer & export demand. % decline in GDP Non-farm employment • Nonfarm jobs nationally fall by 5.3 million -6.0 -5.0 -4.0 -3.0 -2.0 -1.0 0.0 loss of jobs, millions Rural farm • Rural household incomes show significant short-term Rural non-farm decline -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 % decline in average household income The economic losses to Myanmar’s economy in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic will be huge – a drop in production on the order of between 6.4 and 9.0 trillion Kyat – and likely will push the economy into a recession or lead to stagnant growth, at best, for the year. -

Chapter 3, Section 1 – China and Continental Southeast Asia.Pdf

CHAPTER 3 CHINA AND THE WORLD SECTION 1: CHINA AND CONTINENTAL SOUTHEAST ASIA Key Findings • China’s pursuit of strategic and economic interests in Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos often jeopardizes regional environmental conditions, threatens government ac- countability, and undermines commercial opportunities for U.S. firms. • China has promoted a model of development in continental Southeast Asia that focuses on economic growth, to the exclu- sion of political liberalization and social capacity building. This model runs counter to U.S. geopolitical and business interests as Chinese business practices place U.S. firms at a disadvantage in some of Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing economies, particu- larly through behavior that facilitates corruption. • China pursues several complementary goals in continental Southeast Asia, including bypassing the Strait of Malacca via an overland route in Burma, constructing north-south infra- structure networks linking Kunming to Singapore through Laos, Thailand, Burma, and Vietnam, and increasing export opportunities in the region. The Chinese government also de- sires to increase control and leverage over Burma along its 1,370-mile-long border, which is both porous and the setting for conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) and the Burmese military. Chinese firms have invested in exploiting natural re- sources, particularly jade in Burma, agricultural land in Laos, and hydropower resources in Burma and along the Mekong Riv- er. China also seeks closer relations with Thailand, a U.S. treaty ally, particularly through military cooperation. • As much as 82 percent of Chinese imported oil is shipped through the Strait of Malacca making it vulnerable to disrup- tion. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 463 | FEBRUARY 2020 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Intersection of Investment and Conflict in Myanmar By Priscilla Clapp Contents The Belt and Road in Myanmar ....................................3 Promoting Sustainable Development ............................... 5 Impediments to Implementation .............................7 Promoting Development in Conflict Areas ......................... 10 Engaging Civil Society ............... 13 Promoting Peace ........................ 15 Conclusion ................................... 16 Construction workers ride to the site of the Thilawa Special Economic Zone, approximately fifteen miles south of Yangon, on May 8, 2015. (Photo by Soe Zeya Tun/Reuters) Summary • In 2018, Myanmar’s government major political and institutional to bind the two economies ever launched a new policy framework impediments, including military more closely together. for guiding the country’s long-term control of certain political and • To compensate for the lack of gov- development plans. If fully imple- economic sectors, corruption, and ernment capacity to implement mented, the policy would apply armed conflict in the country’s re- the new policy, Naypyidaw would international standards and norms source-rich periphery. be well advised to harness the to its regulation of large-scale de- • Responding to Myanmar’s de- talents of the country’s civil soci- velopment projects undertaken by sire to modernize its infrastruc- ety organizations, many of which commercial and state-owned en- ture, Myanmar and China have are already active in conflict areas terprises and joint ventures. agreed in principle to develop a and could help local communities • The policy, however, is likely to China-Myanmar Economic Cor- ensure that their interests will be remain largely aspirational unless ridor with extensive Chinese in- served by the new investments.