Current Economic Conditions in Myanmar and Options for Sustainable Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses

2019 Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses An Introduction of Business Opportunities and Challenges in Myanmar Prepared by Myanmar Research | Consulting | Capital Markets Contents Introduction 8 Basic Information 9 1. General Characteristics 10 1.1. Geography 10 1.2. Population, Urban Centers and Indicators 17 1.3. Key Socioeconomic Indicators 21 1.4. Historical, Political and Administrative Organization 23 1.5. Participation in International Organizations and Agreements 37 2. Economy, Currency and Finances 38 2.1. Economy 38 2.1.1. Overview 38 2.1.2. Key Economic Developments and Highlights 39 2.1.3. Key Economic Indicators 44 2.1.4. Exchange Rate 45 2.1.5. Key Legislation Developments and Reforms 49 2.2. Key Economic Sectors 51 2.2.1. Manufacturing 51 2.2.2. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 54 2.2.3. Construction and Infrastructure 59 2.2.4. Energy and Mining 65 2.2.5. Tourism 73 2.2.6. Services 76 2.2.7. Telecom 77 2.2.8. Consumer Goods 77 2.3. Currency and Finances 79 2.3.1. Exchange Rate Regime 79 2.3.2. Balance of Payments and International Reserves 80 2.3.3. Banking System 81 2.3.4. Major Reforms of the Financial and Banking System 82 Page | 2 3. Overview of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade 84 3.1. Recent Developments and General Considerations 84 3.2. Trade with Major Countries 85 3.3. Annual Comparison of Myanmar Import of Principal Commodities 86 3.4. Myanmar’s Trade Balance 88 3.5. Origin and Destination of Trade 89 3.6. -

Research Paper 104 July 2018

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 104 July 2018 Food Security Policy Project (FSPP) MYANMAR’S RURAL ECONOMY: A CASE STUDY IN DELAYED TRANSFORMATION By Duncan Boughton, Nilar Aung, Ben Belton, Mateusz Filipski, David Mather, and Ellen Payongayong Food Security Policy Research Papers This Research Paper series is designed to timely disseminate research and policy analytical outputs generated by the USAID funded Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP) and its Associate Awards. The FSP project is managed by the Food Security Group (FSG) of the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU), and implemented in partnership with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Together, the MSU-IFPRI-UP consortium works with governments, researchers, and private sector stakeholders in Feed the Future focus countries in Africa and Asia to increase agricultural productivity, improve dietary diversity, and build greater resilience to challenges like climate change that affect livelihoods. The papers are aimed at researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, educators, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Portuguese, or other languages. Copies of all FSP Research Papers and Policy Briefs are freely downloadable in pdf format from the following Web site: www.foodsecuritypolicy.msu.edu. Copies of all FSP papers and briefs are also submitted to the USAID Development Experience Clearing House (DEC) at: http://dec.usaid.gov/ ii AUTHORS Duncan Boughton is Professor, Ben Belton is Assistant Professor, David Mather is Assistant Professor, and Ellen Payongayong is Specialist, all with International Development, in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU); Nilar Aung is a Consultant with AFRE at MSU; and Mateusz Filipski is Research Fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute. -

The Impact of the Exchange Rate Unification on Trade Balance in Myanmar

THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 Professor Jong-Il YOU THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Jong-Il YOU, Supervisor Professor Chrysostomos TABAKIS Professor Jin Soo LEE Approval as of December, 2016 ABSTRACT This study analyzes the impacts of the exchange rate unification on the trade balance in Myanmar based on Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Model. This paper’s main objective is to determine whether the exchange rate has positive or negative effects on the trade balance. This study has discovered that the exchange rate unification has a positive effect on the trade balance in the long run. Additionally, this study finds that Exchange Rate and Foreign Direct Investment have positive effects on the trade balance while GDP growth rate and Inflation has negative impact in the long run. As a policy implication, this study suggests that the government should focus on economic stability and effective monetary policies within the country. -

Myanmar and FAO Achievements and Success Stories

Myanmar and FAO Achievements and success stories FAO Representation in Myanmar May 2011 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch Communication Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2011 Introduction yanmar economy did not undergo significant structural changes, even though it experienced different political Mand economical systems since it independence in 1948. The country is still an agro-based country in which agriculture sector is the backbone of the economy and main stay of rural economy. Some 20 percent of Myanmar’s 48 million people suffer from undernourishment, confirming that the nation has significant work ahead of it if it is to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of reducing the proportion of people suffering from hunger by half by the year 2015. -

Ids Working Paper

IDS WORKING PAPER Volume 2018 No 513 Energy Protests in Fragile Settings: The Unruly Politics of Provisions in Egypt, Myanmar, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe, 2007 –2017 Naomi Hossain with Fatai Aremu, Andy Buschmann, Egidio Chaimite, Simbarashe Gukurume, Umair Javed, Edson da Luz (aka Azagaia), Ayobami Ojebode, Marjoke Oosterom, Olivia Marston, Alex Shankland, Mariz Tadros, and Kátia Taela June 2018 Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research Programme In a world shaped by rapid change, the Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research programme focuses on fragile, conflict and violence affected settings to ask how social and political action for empowerment and accountability emerges in these contexts, what pathways it takes, and what impacts it has. A4EA is implemented by a consortium consisting of: the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), the Accountability Research Center (ARC), the Collective for Social Science Research (CSSR), the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS), Itad, Oxfam GB, and the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). Research focuses on five countries: Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, and Pakistan. A4EA is funded by UK aid from the UK government. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of our funder. Energy Protests in Fragile Settings: The Unruly Politics of Provisions in Egypt, Myanmar, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe, 2007–2017 Naomi Hossain with Fatai Aremu, Andy Buschmann, Egidio Chaimite, Simbarashe Gukurume, Umair Javed, Edson da Luz (aka Azagaia), Ayobami Ojebode, Marjoke Oosterom, Olivia Marston, Alex Shankland, Mariz Tadros, and Kátia Taela IDS Working Paper 513 © Institute of Development Studies 2018 ISSN: 2040-0209 ISBN: 978-1-78118-449-3 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

Revitalizing Agriculture in Myanmar

Revitalizing Agriculture in Myanmar: Breaking Down Barriers, Building a Framework for Growth Prepared for International Development Enterprises | Myanmar DISTRIBUTION, CITATION, OR QUOTATION NOT PERMITTED WITHOUT PERMISSION July 21, 2010 This paper was written by David O. Dapice ([email protected]), Thomas J. Vallely ([email protected]), and Ben Wilkinson ([email protected]) of the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School and Michael J. Montesano ([email protected]) of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore. The views expressed herein are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect those of IDE, the government of the Union of Myanmar, the Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, or the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. We wish to extend our sincere thanks to our colleagues at IDE/Myanmar and the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation for their contributions to the research and for organizing the complex logistics the assessment demanded. Partial funding for the study was provided by the Royal Norwegian Government. Revitalizing Agriculture in Myanmar July 2010 Page 3 of 64 Distribution, Citation, or Quotation Not Permitted Without Permission of IDE TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP | Union of Myanmar ........................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ -

State Fragility in Myanmar: Fostering Development in the Face of Protracted Conflict

AUGUST 2018 State fragility in Myanmar: Fostering development in the face of protracted conflict Renaud Egreteau Cormac Mangan Renaud Egreteau is Associate Professor in the Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong. Cormac Mangan is a former Country Economist for IGC Myanmar. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to this report: Ian Porter, Nan Sandi, Paul Minoletti, Gerard McCarthy, and Andrew Bauer. Acronyms ASEAN: Association of South East Asian Nations BSPP: Burma Socialist Program Party CPB: Communist Party of Burma FDI: Foreign direct investment GAD: General Administration Department IDPs: Internally displaced people MEC: Myanmar Economic Corporation NLD: National League for Democracy NCA: Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement SMEs: Small and medium enterprises SLORC: State Law and Order Restoration Council SOEs: State-owned enterprises SPDC: State Peace and Development Council UMEHL: Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited USDP: Union Solidarity and Development Party About the commission The LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development was launched in March 2017 to guide policy to address state fragility. The commission, established under the auspices of the International Growth Centre, is sponsored by LSE and University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. It is funded from the LSE KEI Fund and the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Front page photo: Street -

MYANMAR 2014 Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity in a Time of Transition

Report No. 93050-MM NOVEMBER, MYANMAR 2014 Ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity in a time of transition Photo by: Ni Ni Myint/World Bank, 2014 A SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC World Bank Office Yangon No.57, Pyay Road (Corner of Shwe Hinthar Road) 61/2 Mile, Hlaing Township, Yangon Republic of the Union of Myanmar +95 (1) 654824 www.worldbank.org/myanmar www.facebook.com/WorldBankMyanmar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a World Bank Group team from the World Bank – IDA, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) led by Khwima Nthara (Program Leader & Lead Economist) under the direct supervision of Mathew Verghis (Practice Manager, MFM) and Shubham Chaudhuri (Practice Manager, MFM & Poverty). Cath- erine Martin (Principal Strategy Officer) was the IFC’s Task Manag- er. Overall guidance was provided by Ulrich Zachau (Country Direc- tor), Abdoulaye Seck (Country Manager), Kanthan Shankar (Former Country Manager), Sudhir Shetty (Regional Chief Economist), Betty Hoffman (Former Regional Chief Economist), Constantinee Chikosi (Portfolio and Operations Manager), Julia Fraser (Practice Manag- er), Jehan Arulpragasam (Practice Manager), Hoon Sahib Soh (Op- erations Adviser), Rocio Castro (VP Adviser), Antonella Bassani (Strategy and Operations Director), Antony Gaeta (Country Program Coordinator), Maria Ionata (Former Country Program Coordinator),- Vikram Kumar (IFC Resident Representative), and Simon Andrews (Senior Manager). The report drew from thematic input notes prepared by a cross-sec- tion of Bank staff as follows: -

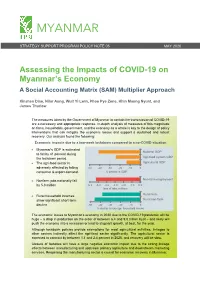

Assessing the Impacts of COVID 19 on Myanmar's Economy

MYANMAR STRATEGY SUPPORT PROGRAM POLICY NOTE 05 MAY 2020 Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19 on Myanmar’s Economy A Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) Multiplier Approach Xinshen Diao, Nilar Aung, Wuit Yi Lwin, Phoo Pye Zone, Khin Maung Nyunt, and James Thurlow The measures taken by the Government of Myanmar to contain the transmission of COVID-19 are a necessary and appropriate response. In-depth analysis of measures of this magnitude on firms, households, government, and the economy as a whole is key to the design of policy interventions that can mitigate the economic losses and support a sustained and robust recovery. Our analysis found the following: Economic impacts due to a two-week lockdown compared to a no-COVID situation • Myanmar’s GDP is estimated National GDP to fall by 41 percent during the lockdown period. Agri-food system GDP • The agri-food sector is Agricultural GDP adversely affected by falling -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 consumer & export demand. % decline in GDP Non-farm employment • Nonfarm jobs nationally fall by 5.3 million -6.0 -5.0 -4.0 -3.0 -2.0 -1.0 0.0 loss of jobs, millions Rural farm • Rural household incomes show significant short-term Rural non-farm decline -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 % decline in average household income The economic losses to Myanmar’s economy in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic will be huge – a drop in production on the order of between 6.4 and 9.0 trillion Kyat – and likely will push the economy into a recession or lead to stagnant growth, at best, for the year. -

Dr. Myo Kywe (Rector, Yezin Agricultural University) Dr. Kyi

Dr. Myo Kywe (Rector, Yezin Agricultural University) Dr. Kyi Toe (Associate Professor, Yezin Agricultural University) 1 Location Between Latitude 9˚32' and 28˚ 31' N Longitude 92˚ 10' and 101˚ 1' E Sharing borders with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand Area is about 676, 577 sq km Extended about 2361 km from north to south About 1078 km from east to west 2 Population 51.702 million (2015) Male 24.936 million Female 26.766 million 1.01% annual growth rate population density 76/ square kilometer Climate Tropical Sub-tropical Temperate Season Winter Summer Raining 3 Agriculture Sector in Myanmar * Source: Myanmar Agriculture in Brief 2015 Myanmar Economy and Agriculture Myanmar is an agricultural country, and agriculture sector is the backbone of its economy. Agriculture sector contributes 22.1 % (2014-1015) of GDP, 20% of total export earnings; and employs 61.2 % of the labor force. Government has laid down the four economic policies of which one of the major economic objective is “Building the modern industrialized nation through the agricultural development, and all-round development of other sectors of the economy”. 5 AGRICULTURAL POLICIES To emphasize production and utilization of high yielding and good quality seeds To conduct training and education activities for farmer and extension staff to provide advanced agricultural techniques To implement research and development activities for sustainable agricultural development To encourage transformation from conventional to mechanized agriculture, production of -

Chapter VI: FDI, Industrial Upgrading and Economic Corridor in Myanmar

Chapter VI: FDI, Industrial Upgrading and Economic Corridor in Myanmar Ni Lar, Chiang Mai University, Thailand Hiroyuki Taguchi, Saitama University, and Visiting Researcher, ESRI This chapter addresses the issues on inward foreign direct investment (FDI), industrial upgrading, and economic-corridor development in Myanmar. We first present the economic profile of Myanmar by comparing with other economies in Mekong region as well as its brief history. Second, we discuss the role of inward FDI in Myanmar. From a short-term perspective, Myanmar needs to accept inward FDI to participate in international production networks and thus to develop a manufacturing sector. This section represents empirical evidence on the linkage between FDI and the growth of GDP and exports, and investigates a specific issue to be addressed for accepting inward FDI in Myanmar manufacturing sector. Third, from a long-term perspective, we discuss the issues on industrial upgrading and geographical linkage in Myanmar economy. Myanmar now depends heavily on natural resource production in its economy, and also on labor-intensive production in its manufacturing sector. Thus, the industrial reformation should address how to diversify its industries towards a variety of manufacturing sectors and how to upgrade its industries towards upstream and high-valued manufacturing sectors. From the geographical viewpoint, Myanmar also now depends on spot-area development through its SEZ framework. For extending the economic impacts of the SEZ development to nation-wide level, the SEZ development should contribute to an economic corridor approach linked with 102 neighboring countries. 1. Economic Profile of Myanmar This section first presents the economic profile of Myanmar by comparing with other economies in Mekong region, and then reviews its brief history and the recent economic reforms.1 Economic Profile of Myanmar Myanmar has just opened up its economy and started its economic reforms under President U Thein Sein since March 2011.