Case Studies from Afghanistan and Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice Within Marriage in Nepal

Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice within Marriage in Nepal By Inku Subedi B.A., Lafayette College, 2005 M.A. Brown University, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Inku Subedi This dissertation by Inku Subedi is accepted in its present form by the Department of Sociology as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Michael J. White , Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council ______________ __________________________________________ Date Nancy Luke, Committee Member ______________ __________________________________________ Date Leah VanWey, Committee Member ______________ __________________________________________ Date David P. Lindstrom, Reader ______________ __________________________________________ Date Carrie Spearin, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council ______________ __________________________________________ Date Paul M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION Brown University, Providence RI Ph.D. in Sociology 2014 Dissertation Title: "Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice within Marriage in Nepal" M.A., Sociology 2008 Thesis title “Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Transition into Premarital Romantic Relationship, Sexual Activity, and Marriage in the Gilgel Gibe -

Digital Soil Mapping in the Bara District of Nepal Using Kriging Tool in Arcgis

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications Agronomy and Horticulture Department 10-26-2018 Digital soil mapping in the Bara district of Nepal using kriging tool in ArcGIS Dinesh Panday University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Bijesh Maharjan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Devraj Chalise Nepal Agricultural Research Council Ram Kumar Shrestha Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Lamjung, Nepal Bikesh Twanabasu Westfalische Wilhelms Universitat, Munster Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agriculture Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Botany Commons, Horticulture Commons, Other Plant Sciences Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Panday, Dinesh; Maharjan, Bijesh; Chalise, Devraj; Shrestha, Ram Kumar; and Twanabasu, Bikesh, "Digital soil mapping in the Bara district of Nepal using kriging tool in ArcGIS" (2018). Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications. 1130. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/1130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy and Horticulture Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESEARCH ARTICLE Digital soil mapping in the Bara district of Nepal using kriging tool in ArcGIS 1 1 2 3 Dinesh PandayID *, Bijesh Maharjan , Devraj Chalise , Ram Kumar Shrestha , Bikesh Twanabasu4,5 1 Department of Agronomy and Horticulture, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States of America, 2 Nepal Agricultural Research Council, Lalitpur, Nepal, 3 Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Lamjung Campus, Lamjung, Nepal, 4 Hexa International Pvt. -

DFID Stabilisation Unit Guide

The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation A guide for policy makers and practitioners The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation A guide for policy makers and practitioners March 2019 Contents Foreword by the Right Hon Alistair Burt MP 4 Introduction from the Director of the Stabilisation Unit 6 The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation 10 Chapter 1: The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation 12 What is stabilisation? 13 Stabilisation principles 18 Chapter 2: Stabilisation in practice – essential elements for effective delivery 30 Introduction 31 Essential element 1: Driving factors – context, objectives and relationships 33 Essential element 2: Thinking and working politically 38 Essential element 3: Understanding – learning, honesty and adaptability 39 Essential element 4: Strategy – coherence, realism and integration 44 Essential element 5: Behaviour – humility, sensitivity and communication 50 Essential element 6: Monitoring, evaluation and learning 55 Essential element 7: Planning for transition 57 Chapter 3: Stabilisation, security and justice 60 Introduction 61 Addressing security and justice issues as an essential component of stabilisation 62 Direct security provision in stabilisation contexts 64 Understanding and analysing security and justice in stabilisation contexts 66 Thinking and working politically when delivering security and justice interventions 70 Specific types of security and justice interventions in stabilisation contexts 75 Delivering effective security and justice interventions in stabilisation contexts -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

WKW Creating-New-Spaces-Afghanistan

Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan A Case of Istalif and Kalakan Districts in Kabul Province 2 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Acknowledgements Author: Mariam Jalalzada Contributing Partner Organisation: Afghan Women’s Resource Center (AWRC) Design: Dacors Design This research study was made possible by the efforts of the programme staff of the Afghan Women’s Resource Center in Kalakan and Istalif Districts of Kabul Province – especially Samira Aslamzada. Their efforts in organising the field trips, focus group discussions with the women, and interviews with various individuals, is to be lauded. Special thanks are due to Durkhani Aziz for her kindness and her relentless role as co-facilitator during the entire fieldwork, ensuring attendance of Community Development Council (CDC) members and Government officials in the focus group discussions and interviews. My sincere thanks to the CDC members for taking the time and effort to attend the discussions and to talk about their personal lives, and to the Governmental representatives for their helpful engagement with this research. October 2015 3 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................2 Acronyms............................................................................................................................4 Executive summary ........................................................................................................5 -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

Learning Nepali the Soas Way

REVIEW ARTICLE LEARNING NEPALI THE SOAS WAY Mark Turin Himalayan Languages Project Leiden University The Netherlands Teach Yourself Nepali: A Complete Course in Understanding, Speaking and Writing. 1999. Michael Hutt and Abhi Subedi. London: Teach Yourself Books, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. xi + 308 pages. 2 cassettes. UK book price: £14.99. Nepali price: Nrs 465. ISBN 0-340-71130-2. Introduction Despite being relatively small both in terms of size and population, Nepal and her national language have exerted a considerable influence across the northern reaches of South Asia. Home to more than 80 languages hailing from four different language families, Nepal has more need of a common tongue than many other countries twice her size. Outside of Nepal’s present borders, Nepali is widely used in Sikkim and Darjeeling, prompting its recognition as a major language in India by the Indian Constitution. Even in the mountainous kingdom of Bhutan, the Nepali language is both spoken and understood. Nepali is, in short, a lingua franca of the central and eastern Himalaya. Since the opening of Nepal ’s borders in 1951, a whole new group of potential Nepali language learners has emerged. Foreign volunteers, teachers, doctors, academics, missionaries, hippies and businessmen, to mention but a few of the interest groups coming to Nepal, have all sought to learn the national language over the past 40 years. It is surprising that despite the high profile of these visitors to Nepal and their relatively large numbers, no single pedagogical textbook has emerged which answers their needs. On one level, of course, the diversity of these foreign learners and their differing priorities provides the explanation. -

Study Report on "Comminity Based Organizations(Cbos): Landscape

Community Based Organizations (CBOs): Landscape, Capacity Assessment and Strengthening Strategy Study Report Prepared for PLAN Nepal Lalitpur, Nepal July, 2005 Democratizing civil society at grassroots SAGUN P.O. Box 7802, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: 977 4247920, Fax: 9771 4229544 Email: [email protected] Community Based Organizations (CBOs): Landscape, Capacity Assessment and Strengthening Strategy Mukta S. Lama Suresh Dhakal Lagan Rai Study Report Prepared for PLAN Nepal Lalitpur, Nepal July, 2005 SAGUN P.O. Box 7802, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: 977 4247920, Fax: 9771 4229544 Email: [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report is a result of contribution of many people in multiple ways. Foremost, we extend our deepest and heartfelt gratitude to members of Community Based Organizations across the districts for sharing us with their time, insight and experiences. The study benefited greatly from support and cooperation of the Plan field staff and partner agencies in Sunsari, Morang, Makwanpur, Rautahat, Bara, and Banke districts and the Regional Operational Support Unit teams. We would like to thank Ms. Chhing Lamu Sherpa, Mr. Kalbhan Rai, Dr. Chandra K. Sen, Mr. R. P. Gupta and Krishna Ghimire for their valuable inputs on the study. Dr. Chandi Chapagai, Plan Nepal Country Training Coordinator deserves special thanks for coordinating the whole exercise. We would like to express our deep appreciation to Shobhakar Vaidhya for his keen interest, insightful comments and his enthusiasm for incorporating the learning into the institutional policies and procedures. Thanks are also due to the Ms. Minty Pande, Country Director for her encouragement and comments. Similarly we very much appreciate the support of Mr. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal Forests for Prosperity Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) March 8, 2020 Executive Summary 1. This Environment and Social Management Framework (ESMF) has been prepared for the Forests for Prosperity (FFP) Project. The Project is implemented by the Ministry of Forest and Environment and funded by the World Bank as part of the Nepal’s Forest Investment Plan under the Forest Investment Program. The purpose of the Environmental and Social Management Framework is to provide guidance and procedures for screening and identification of expected environmental and social risks and impacts, developing management and monitoring plans to address the risks and to formulate institutional arrangements for managing these environmental and social risks under the project. 2. The Project Development Objective (PDO) is to improve sustainable forest management1; increase benefits from forests and contribute to net Greenhouse Gas Emission (GHG) reductions in selected municipalities in provinces 2 and 5 in Nepal. The short-to medium-term outcomes are expected to increase overall forest productivity and the forest sector’s contribution to Nepal’s economic growth and sustainable development including improved incomes and job creation in rural areas and lead to reduced Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and increased climate resilience. This will directly benefit the communities, including women and disadvantaged groups participating in Community Based Forest Management (CBFM) as well and small and medium sized entrepreneurs (and their employees) involved in forest product harvesting, sale, transport and processing. Indirect benefits are improved forest cover, environmental services and carbon capture and storage 3. The FFP Project will increase the forest area under sustainable, community-based and productive forest management and under private smallholder plantations (mainly in the Terai), resulting in increased production of wood and non-wood forest products. -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

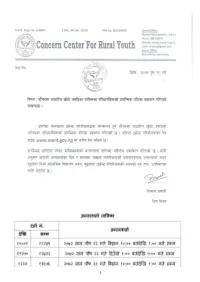

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C.