Learning Nepali the Soas Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice Within Marriage in Nepal

Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice within Marriage in Nepal By Inku Subedi B.A., Lafayette College, 2005 M.A. Brown University, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Inku Subedi This dissertation by Inku Subedi is accepted in its present form by the Department of Sociology as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Michael J. White , Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council ______________ __________________________________________ Date Nancy Luke, Committee Member ______________ __________________________________________ Date Leah VanWey, Committee Member ______________ __________________________________________ Date David P. Lindstrom, Reader ______________ __________________________________________ Date Carrie Spearin, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council ______________ __________________________________________ Date Paul M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION Brown University, Providence RI Ph.D. in Sociology 2014 Dissertation Title: "Gender Differences in Migration, Marital Timing, and Spousal Choice within Marriage in Nepal" M.A., Sociology 2008 Thesis title “Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Transition into Premarital Romantic Relationship, Sexual Activity, and Marriage in the Gilgel Gibe -

Migration to and from the Nepal Terai: Shifting Movements and Motives Hom Nath Gartaula and Anke Niehof

Migration to and from the Nepal terai: shifting movements and motives Hom Nath Gartaula and Anke Niehof Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 29–51 | ISSN 2050-487X | journals.ed.ac.uk/southasianist journals.ed.ac.uk/southasianist | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 29 Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 29-51 Migration to and from the Nepal terai: shifting movements and motives Hom Nath Gartaula University of Manitoba, Canadian Mennonite University, [email protected] Anke Niehof Wageningen University, [email protected] In Nepal, the historical evidence shows that migration to the terai increased after the eradication of malaria in the late 1950s and has been increasing ever since. More recently, however, out-migration from the terai is rapidly increasing. By applying both qualitative and quantitative research methods, in-depth qualitative interviews, focus group discussions and household survey were used for data collection, with considerable inputs from ethnographical fieldwork for about 21 months. The paper presents three types of population flows in the historical pattern. First, the history of Nepal as an arena of population movement; second, the gradual opening up of the terai, leading to the hills-terai movement; and the third, the current outward flow as an individual migration for work. The paper exemplifies that poverty and lack of arable land are not the only push factors, but that pursuing a better quality of life is gaining importance as a migration motive. We conclude that like movements of people, their motives for moving are also not static and cannot be taken for granted. journals.ed.ac.uk/southasianist | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. -

SN Applicant Name Alotted Kitta BOID 1 AMBIKA DAHAL 10

Nepal Agro Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha IPO Result Alotted SN Applicant Name Kitta BOID 1 AMBIKA DAHAL 10 1301720000008683 2 MAHESHWORI DHUNGANA 10 1301120000464481 3 SHIVA SHANKAR BHANDARI 10 1301090000039971 4 Deepa Devkota 10 1301440000013531 5 SANTOSH KUNWAR YOGI 10 1301720000051011 6 DHAN MAYA DANGOL 10 1301250000126233 7 buddi bdr phuyal 10 1301250000044258 8 SANGITA REGMI 10 1301720000055244 9 SHAMBHAVI ACHARYA 10 1301330000049364 10 SUSHILA SUBEDI NEUPANE 10 1301120000349033 11 RAMITA PAUDYAL 10 1301350000075141 12 CHANDRAKALA BHATTRAI 10 1301120000329156 13 BINITA ARYAL 10 1301140000101320 14 NIRAJ KUMAR JOSHI 10 1301060000064699 15 Bhoj Prasad Gautam 10 1301070000266927 16 RAMILA DHUNGEL 10 1301390000059945 17 MAYA SHERPA 10 1301060001350941 18 Keshari Tandukar 10 1301120000378867 19 MADHAB PRASAD KOIRALA 10 1301390000012256 20 SANU SHARMA POUDEL 10 1301060000344816 21 PALPASA BHARATI 10 1301100000083422 22 DIPENDRA KUMAR AIER 10 1301310000094293 23 DIL KUMAR THAPA 10 1301020000257222 24 GEETA TANDAN 10 1301190000090746 25 KARNA BAHADUR THAPA MAGAR 10 1301720000046417 26 ANANDA PAUDEL 10 1301060000932335 27 REEWAZ BAR SINGH THAPA 10 1301720000066936 28 RITIMA THAPA 10 1301720000067000 29 AADITYA CHAUDHARY 10 1301720000026466 30 NIRAJ KARKI 10 1301720000012738 31 MITRA LAL LAMSAL 10 1301080000267934 32 SABITRA POKHREL 10 1301040000042248 33 PRAMILA JOSHI 10 1301480000096056 34 DURGA KUMARI ADHIKARI 10 1301090000646127 35 TULASA BASNET 10 1301720000033015 36 SITA SHARMA 10 1301220000015415 37 DEBAKI KAFLE 10 1301090000364095 38 -

Election-Result- 2021

Non-Resident Nepali Association National Coordination Council of USA National Election Commission (2021) Chief- Election Commissioner: Biswa N. Baral Election Commissioners: Bashu D. Phulara ESQ., Govinda K. Shrestha, Kul M. Acharya, Shiva R. Poudel Preliminary Result VOTE S.No CANDIDATE'S NAME POSITION RECEIVED POSITION Name President - National 1 Buddi S Subedi 5618 Winner 2 Dr Arjun Banjade 4148 3 Krishna P Lamichhane 5200 4 Tilak B KC 567 Name Senior Vice President - National 1 Babu Ram Lama 5563 2 Chitra Karki 2663 3 Krishna Jibi Pantha 6850 Winner Name Vice President - National 1 Ammar Bahadur Chhantyal 3126 2 Basudev Adhikari 4208 3 Bikash Upreti 4433 Winner 4 Chandra Lama 3369 5 Dilu Ram Parajuli 5097 Winner 6 Gopendra Raj Bhattrai 5496 Winner 7 Kishor Regmi 1065 8 Prabin KC 4049 9 Prakash Basnet 2358 10 Purna Chandra Baniya 2107 11 Ram Hari Adhikari 4296 12 Roshan Adhikari 1577 13 Suman Thapa 5975 Winner 14 Tank R Regmi 2147 Name Women Vice President - National 1 Diksha Basnet 8245 Winner 2 Kranti Aryal Bhandari 6466 Name General Secretary - National 1 Anjan Kumar Chaulagai 6312 Winner 2 Binod Bhatta 5145 3 Nabaraj Subedi 785 4 Nripendra Dhital 2509 Name Secretary (Open) - National 1 Anup Khanal 5957 Winner 2 Drona Gautam 5221 3 Narayan P Pokharel 3473 Name Secretary (Women) - National 1 Sunita Sapkota Kandel 7703 Winner 2 Tara Dhakal Marahatta 6872 Name Treasurer - National 1 Rajeev Prasad Shrestha 8808 Winner 2 Satendra Kumar Shah 5795 Name Joint Treasurer - National 1 Agni Prasad Dhakal 6206 Winner 2 Bikal Dhakal 4637 3 Rabindra -

Recent Works in Western Languages on Nepal and the Himalayas

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 20 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin no. 1 & Article 14 2 2000 Recent Publications - Recent Works In Western Languages on Nepal and the Himalayas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 2000. Recent Publications - Recent Works In Western Languages on Nepal and the Himalayas. HIMALAYA 20(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol20/iss1/14 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT PUBLICATIONS RECENT WORKS IN WESTERN LANGUAGES ON NEPAL AND THE HIMALAYAS: Gregory G. Maskarinec gregorym @hawaii .edu This list seeks to resurrect a formerly regular feature of the Himalayan Research Bul/etilz. It notes works that have appeared in the past six years, primarily books on Nepal but also articles that have come to my attention and also some publications on the wider Himalayan region. As newly appointed contributing editor of the Himalayan Research Bulletin for recent publications, I hope to compile annually a list similar to this. Future lists will be more extensive, particularly in regard to journal articles, which have been slighted here. Achieving greater comprehensiveness will require assistance, so I invite all readers to submit bibliographic entries, of their own works or of any material that has come to their attention, to me at Acharya, Madhu Raman. -

Anma Newsletter Association of Nepalese Mathematicians in America

Issue 2 MAY 2018 ANMA NEWSLETTER ASSOCIATION OF NEPALESE MATHEMATICIANS IN AMERICA Dear ALL, I trust that this issue of the ANMA newsletter will find you well. Let me begin by thanking you all for your tremendous and continuous encouragement to our activities. Because of your support and strong team efforts within the ANMA executive committee, we have been able to move forward bringing ANMA into a greater height. Since the beginning of our term, we have made substantial progress. In collaboration with Nepal Mathematical Society (NMS), we have successfully established scholarships in Nepal for two students (one male and one female) who secure the highest marks in the master’s entrance examination. We successfully organized number of workshops and interaction programs in Nepal. We also Naveen K. Vaidya published two proceedings from the last conference (International Conference on Applications of Mathematics to Nonlinear Sciences - 2016) EDITORIAL: It is a great in “Electronic Journal of Differential Equations” and “Neural, Parallel, and pleasure to present the Scientific computations”. second issue of ANMA Newsletter. We would like to Most notably, we are organizing a “Workshop on Collaborative Research in thank the entire team of Mathematical Sciences” on May 25-27, 2018 at Mercer University, Georgia. ANMA for providing us with I believe that this unique initiative within our organization will provide us a this wonderful opportunity and material support. We have great opportunity for initiating collaborative research among Nepalese tried our best effort to mainly mathematicians in America. This will eventually offer a platform to extend present the recent ANMA opportunities for collaboration with mathematicians in Nepal. -

Curriculum Vitae

January, 2021 Curriculum Vitae Mahesh Jaishi Tarkeshwor-5, Kathmandu Date of birth: 2027-11-27 (1971-03-11) Mobile: 9851242042, Email: [email protected] [email protected] Academic qualification Degree Institute Division M. Sc. (Extension education) 2005 IAAS, Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal Distinction Major subjects in M. Sc.: Agricultural Extension and Rural Sociology Thesis: Impact of Rural-Urban Partnership Program (RUPP/UNDP) on Human Resource Development: A Case from Rupandehi district, Nepal. Job experiences: Position, duration and employer Job responsibilities Academic related experiences Assistant Professor • Teaching and guide undergraduates and post Agriculture Extension graduates for agriculture extension subject Department of social Science • Guide to student for Undergraduate Practicum Institute of Agriculture and Animal assessment (UPA) program as a partial fulfillment Science (IAAS), Lamjung Campus of course of B.Sc. (Ag.) • Guide Post graduate student for thesis research and February 2014 to till date documentation as a partial fulfillment Assistant Campus Chief • To assist and support the Campus Chief to execute, plan, monitor the overall academic and administrative activities of the Campus as per the vision, mission and goal of IAAS • Collaborate and liaison IAAS and Lamjung Campus for academic and administrative achievement • Act as a Chair of Annex program comittee of the campus Head of department (July2017-till) • Ensure, facilitate, monitor the teaching learning Department of Agri-economics Agri activities of B.Sc. -

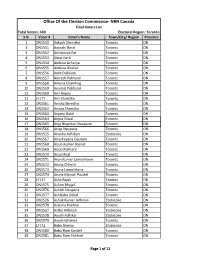

General Members to Post.Xlsx

Office Of the Election Commission- NRN Canada Final Voters List Total Voters: 449 Electoral Region: Toronto S N Voter # Voter's Name Town/City/ Region Province 1 ON1550 Aakash Shrestha Toronto ON 2 ON1551 Aayushi Baral Toronto ON 3 ON1552 Aishworya Rai Toronto ON 4 ON1553 Amar Karki Toronto ON 5 ON1554 Ambika Acharya Toronto ON 6 ON1555 Ambika Dhakal Toronto ON 7 ON1556 Amit Dallakoti Toronto ON 8 ON1557 Amresh Pokharel Toronto ON 9 ON1558 Amuna Chamling Toronto ON 10 ON1559 Anamol Pokharel Toronto ON 11 ON1560 Anil Regmi Toronto ON 12 LF177 Anil Shrestha Toronto ON 13 ON1561 Anisha Shrestha Toronto ON 14 ON1562 Anissa Shrestha Toronto ON 15 ON1563 Anjana Dulal Toronto ON 16 ON1564 Anjira Silwal Toronto ON 17 ON1565 Anju Bhandari Neupane Toronto ON 18 ON1566 Anup Neupane Toronto ON 19 ON1525 Anusha Adhikari Etobicoke ON 20 ON1567 Anushayana Gautam Toronto ON 21 ON1568 Arjun Kumar Basnet Toronto ON 22 ON1569 Arjun Pokharel Toronto ON 23 ON1570 Arjun Rijal Toronto ON 24 ON1571 Arun Kumar Lamichhane Toronto ON 25 ON1572 Aruna Chhetri Toronto ON 26 ON1573 Aruna Lamichhane Toronto ON 27 ON1574 Aruna Mainali Poudel Toronto ON 28 LF137 Asha Rajak Toronto ON 29 ON1575 Ashim Bhujel Toronto ON 30 ON1576 Ashish Neupane Toronto ON 31 ON1577 Ashlesha Dahal Toronto ON 32 ON1526 Ashok Kumar Adhikari Etobicoke ON 33 ON1578 Aslesha Pokhrel Toronto ON 34 ON1527 Astha Adhikari Etobicoke ON 35 ON1528 Ayush Adhikari Etobicoke ON 36 ON1579 Ayush Ghimire Toronto ON 37 LF172 Baba Shakya Etobicoke ON 38 ON1580 Babu Ram Kandel Toronto ON 39 ON1581 Babu Ram Pokhrel -

ANMA Newsletter 2020

ANMA NEWSLETTER ASSOCIATION OF NEPALESE MATHEMATICIANS IN AMERICA Message from the President ISSUE 3 1 Editorial This issue of the ANMA newsletter is a small effort to extend the ambit of our friendship by gathering and disseminating accomplishments and experiences of Nepalese mathematicians and statisticians in Nepal, the United States, and around the globe. Abided by the motivation of connecting the mathematics community of Nepal together, we were able to organize different activities that foster perseverance, trust, and teamwork between us. While conducting each of these activities, we were aware that the voices of each of the members will not go unheard. Now that our journey as the executive committee member is at the end, we would like to present the works, accomplishments, and achievements of the bigger and growing family of Nepali mathematicians in the U.S.A. Being a member of ANMA provides a specific opportunity to give back to our communities while working with a passionate and talented group of people. We believe that the fastest way to grow our network is to import our contacts into our organization and find more people who can serve ANMA with their knowledge and experiences. We are continuously looking into different ways to bring more members of our community under the umbrella of our organization. We are also very excited to share that this year ANMA reached over 100 members. Even during the year of unprecedented changes and challenges, ANMA remained committed to the needs and concerns of its members and organized various activities virtually. We believe that this issue will translate the passion, friendship, achievements, and energy we all ANMA members shared throughout these two years. -

America Nepal Society, Washington, DC, MEMBERSHIP LIST -2011/2012

America Nepal Society, Washington, DC, MEMBERSHIP LIST ‐2011/2012 S.N Head of the House Family Member Phone NumberCITY state Last Name First Name 1 Thapa Bijay Archana Ghimire 703.855.2579South Riding VA 2 Dawadi Mukti Ambika dawadi 703.915.9957Falls Church VA 3 Shrestha Manoj MD 4 Pudasaini Thakur 703.565.4697Manassas VA 5 Dahal Ojaswi 240.478.4102Gaithersburg MD 6 Tiwari Loknath 301.332.1427 MD 7 Gurung Dinesh 410.288.8123 MD 8 Bhandary Chetnath 310.332.1427 MD 9 Tiwari Tilak MD 10 Neupane Goma Falls Church VA 11 Neupane Sushil Kalpana 301.755.3328Falls Church VA 12 Shrestha Pramesh VA 13 Shah Vijaya 703.931.1721Falls Church VA 14 Gaudel Laxmi 703.280.8782Chantilly VA 15 Baral Keshab Gayatir 571.216.8951Chantilly VA 16 Shrestha Rajesh 703.996.6476Woodbridge VA 17 kc Subu 703.851.2970South Riding VA 18 Dahal Kedar Chantilly VA 19 Malakar Ram Silver spring MD 20 Sharma Hari 703.307.7151 MD 21 Sangraula Prem 703.356.3874Falls Church VA 22 Kharel Narayan MD 23 Maharjan Ganga MD 24 Ranjit Ratna MD 25 Thapa Rabina Narayan Thapa 443.839.6555Baltimore MD 26 Niraula Rita MD 27 Maharjan Bijay MD 28 Shrestha Neeta MD 29 Karki Rup Ashburn VA 30 Sharma Bidya VA 31 Thapa Sundar MD 32 Sharma Dhaneswar 240.421.3625Gaithesburg MD 33 Khanal Krishna Chantilly VA 34 Sangraula Khem 703.759.9181Chantilly VA 35 Sharma Anand Arlington VA 36 Tiwari Sudip Ranjana TiwariFalls Church VA 37 Koirala Shankar VA 38 Pandey Gyan 39 Bhandary Madusudan 40 Dhakal Lal krishna 41 Pokhrel Kali Prasad Arlington VA 1 America Nepal Society, Washington, DC, MEMBERSHIP LIST ‐2011/2012 -

Decision Makers' Perception and Knowledge About Ltcin Nepal: An

ABSTRACT DECISION-MAKERS’ PERCEPTIONS AND KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LONG-TERM CARE IN NEPAL: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY by Kelina Basnyat Understanding issues related to long-term care (LTC) is more prominent in western countries than in developing countries. Many developing countries including Nepal are passing through a process of modernization which is replacing traditional social structures and value systems. For example in Nepal, even though long-term care is sometimes provided by a very limited number of government funded old age homes and non-profit organizations, the family remains the sole care-taker for most elderly. Research has demonstrated that the modern ideology of individualism along with the growing number of nuclear families is placing vulnerable populations such as the elderly in a difficult predicament. It is thus safe to argue that if decision- makers of Nepal lack basic knowledge of needs related to aging, disability, and LTC, this will impact all policies concerning these issues. This paper, therefore, explores the perception and knowledge pertaining to aging, disability and LTC among key decision-makers (bureaucrats and politicians) of Nepal. This exploratory study was conducted in Kathmandu and involved face-to- face in-depth interviews with 18 decision makers. The findings reveal that decision-makers have limited knowledge about aging, disability in aging and LTC needs. This paper maintains that the formulation and implementation of any new policies regarding aging and LTC needs could be problematic due to the unstable Nepali political climate. DECISION MAKERS’ PERCEPTIONS AND KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LONG-TERM CARE IN NEPAL: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Gerontological Studies Department of Sociology and Gerontology by Kelina Basnyat Miami University Oxford, OH 2009 Advisor _____________________________ Dr. -

Constituent Assembly Election 2064: List of Winning Candidates

Constituent Assembly Election 2064: List of Winning Candidates No. District Const Candidate Name Party Name Gender Age Ethnicity Total Votes 1 Taplejung 1 Surya Man Gurung Nepali Congress M 64 Janajati 8719 2 Taplejung 2 Damber Dhoj Tumbahamphe Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 50 Janajati 8628 3 Panchthar 1 Purna Kumar Serma Nepali Congress M 64 Janajati 12920 4 Panchthar 2 Damber Singh Sambahamphe Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 45 Janajati 12402 5 Ilam 1 Jhal Nath Khanal Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 58 Bahun 17655 6 Ilam 2 Subash Nembang Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 55 Janajati 17748 7 Ilam 3 Kul Bahadur Gurung Nepali Congress M 73 Janajati 16286 8 Jhapa 1 Dharma Prasad Ghimire Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 62 Bahun 15276 9 Jhapa 2 Gauri Shankar Khadka Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 47 Chhetri 18580 10 Jhapa 3 Purna Prasad Rajbansi Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 43 Janajati 16685 11 Jhapa 4 Dharma Sila Chapagain Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) F 35 Bahun 19289 12 Jhapa 5 Keshav Kumar Budhathoki Nepali Congress M 64 16466 13 Jhapa 6 Dipak Karki Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 47 Chhetri 14196 14 Jhapa 7 Bishwodip Lingden Limbu Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 32 Janajati 16099 15 Sankhuwasabha 1 Purna Prasad Rai Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 43 Janajati 12948 16 Sankhuwasabha 2 Dambar Bahadur Khadka Communist Party of Nepal (UML) M 42 Chhetri 10870 17 Tehrathum 1 Tulsi Subba Nepali Congress M 52 Janajati 19113 18 Bhojpur 1 Padam Bahadur Rai Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) M 41 Janajati 15796 19