Mediating Transitions Local Radio and the Negotiations of Citizenship in Rural Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

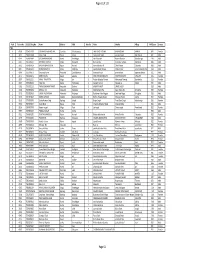

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

The Geographical Journal of Nepal Vol. 12: 1-24, 2019 Central Department of Geography, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal

Volume 12 March 2019 JOURNAL OF NEPAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL ISSN 0259-0948 (Print) THE GEOGRAPHICAL ISSN 2565-4993 (Online) Volume 12 March 2019 JOURNAL OF NEPAL In this issue: THE GEOGRAPHICAL Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into sectoral policies in Nepal: A review Pashupati Nepal JOURNAL OF NEPAL Scale and spatial representation: Restructuring of administrative boundary and GIS mapping in Bajhang district, Nepal Shobha Shrestha Landscape dynamics in the northeast part of Andhikhola watershed, Middle hills of Nepal Chhabi Lal Chidi; Wolfgang Sulzer; and Pushkar Kumar Pradhan Tracing livelihood trajectories: Patterns of livelihood adaptations in rural communities in eastern Nepal Phu Doma Lama; Per Becker; and Johan Bergström Distribution patterns of sugar industry in eastern Uttar Pradesh, India Anil Kumar Tiwari; and V. N. Sharma Commercial vegetable farming: Constraints and opportunities of farmers in Kirtipur, Nepal 12 March 2019 Volume Mohan Kumar Rai; Pashupati Nepal; Dhyanendra Bahadur Rai; and Basanta Paudel Reciprocity between agricultural management and productivity in Nawalparasi district Bhola Nath Dhakal Institutions and rural economy in Rolpa district of Nepal Shiba Raj Pokhrel Central Department of Geography Central Department of Geography Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Tribhuvan University Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal About the journal Guidelines and instructions for authors An annual publication of the Central Department of Geography, the Geographical Journal Authors are expected to submit articles in clear and concise English. Articles should of Nepal has the score One Star from AJOL/INASP Journal Publishing Practices and Standards (https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/index). The journal is designed to stimulate be written in the third person, impersonal style, and use of ‘I/we’ should be avoided. -

Rolpa-District-Prayer-Guide-Nepali

g]kfn b]zsf] nfuL k|fy{fgf ug{' xf]: ?s'd ;Nofg /f]Nkf Ko"7fg bfª /fKtL, /f]Nkf o]z" v|Li6sf] gfpFdf ;a}nfO{ ho dl;x Û xfd|f] ;'Gb/ b]zsf] x/]s ufpFsf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug{ cfk"mnfO{ xfdL ;Fu} ;lDk{t ug'{ ePsf] nfuL wGojfb lbbF5f}+ . o]z" cfk}mn] x/]s ufpFnfO{ k|]d ug'{ x'GYof] eGg] gd'gf cfkmgf] ;]jfsfO{sf] ;dodf cfkmg} r]nfx?nfO{ Pp6f zx/ b]lv csf]{ ufFpx?df hfFbf b]vfpg' eof] . csf]{ s'/f], o]z" cfkm}n] cfkmgf] r]nfx?nfO{ cfk'mn] u/]em}+ ug{ l;sfpg] / ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg] sfd ug'{ eof] . afbdf, pxfFn] ;Q/L hgfnfO{ klg b'O{–b'O{ hgf u/L ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg' eof] . n'sf *–!) cWofo . t/, xfdLx?n] cfh s;/L xfd|f] b]z g]kfnsf] #,(*$ uf=lj=;= sf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug]{< gx]Dofxsf] ;dodf, o?zn]dsf] kv{fn elTsPsf] va/ ox'bfsf bfHo–efO{x?n] NofP . o; kf7df kv{fn zAbn] /Iff, ;'/Iff, cflzif clg Pp6f eljiosf] cfzf b]vfpFb5 . gx]Dofxn] k|fy{gf u/], pkjf; a;], clg dflg;x?sf] kfksf] lglDt kZrtfk klg u/] . k/dk|e'n] gx]Dofxsf] k|fy{gfsf] pQ/ lbg'eof] . w]/} 7"nf] lhDd]jf/L ;f/f kv{fn k'g lgdf0f{ ug'{ kg]{ sfd pxfFsf] cflzif / cg'u|xdf ;Defj eof] . x/]sn] w]/} lj/f]w / ;tfj6 ;fdfgf ug'{ k/]tf klg cfkmgf] c3f8Lsf] kv{fnsf] lgdf0f{ ul//x] . o;/Lg}, xfd|f] nflu x/]s ufpF kv{fnsf] Pp6f O§f h:t} xf] . -

Saath-Saath Project

Saath-Saath Project Saath-Saath Project THIRD ANNUAL REPORT August 2013 – July 2014 September 2014 0 Submitted by Saath-Saath Project Gopal Bhawan, Anamika Galli Baluwatar – 4, Kathmandu Nepal T: +977-1-4437173 F: +977-1-4417475 E: [email protected] FHI 360 Nepal USAID Cooperative Agreement # AID-367-A-11-00005 USAID/Nepal Country Assistance Objective Intermediate Result 1 & 4 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Program Management ........................................................................................................................... 6 III. Technical Program Elements (Program by Outputs) .............................................................................. 6 Outcome 1: Decreased HIV prevalence among selected MARPs ...................................................................... 6 Outcome 2: Increased use of Family Planning (FP) services among MARPs ................................................... 9 Outcome 3: Increased GON capacity to plan, commission and use SI ............................................................ 14 Outcome -

C E N T R a L W E S T E

Bhijer J u m l a Saldang N E P A L - W E S T E R N R E G I O N Patarasi Chhonhup f Zones, Districts and Village Development Committees, April 2015 Tinje Lo M anthang Kaingaon National boundary Zone boundary Village Development Comm ittee boundary Phoksundo Chhosar Region boundary District boundary Gothichour Charang Date Created: 28 Apr 2015 Contact: [email protected] Data sources: WFP, Survey Department of Nepal, SRTM Website: www.wfp.org 0 10 20 40 Rim i Prepared by: HQ, OSEP GIS The designations employed and the presentation of material in M I D - W E Dho S T E R N the map(s) do not imply the expression of any opinion on the Kilom eters part of WFP concerning the legal or constitutional status of any Map Reference: country, territory, city or sea, or concerning the delimitation of its ± frontiers or boundaries. Sarmi NPL_ADMIN_WesternRegion_A0L Pahada © World Food Programme 2015 Narku Chharka Liku Gham i Tripurakot Kalika K A R N A L I FAR-W ESTERN Lhan Raha MID-W ESTERN BJ a Hj a Er kRo It Surkhang Bhagawatitol Juphal D o l p a M u s t a n g W ESTERN Lawan Suhu Chhusang CENTRAL Gotam kot EASTERN Dunai Majhphal Mukot Kagbeni Sahartara Jhong Phu Nar Syalakhadhi Sisne Marpha Muktinath Jom som Tangkim anang Tukuche Ranm am aikot M a n a n g Baphikot Jang Pipal Pwang R u k u m Kowang Khangsar Ghyaru Mudi Pokhara M y a g d i Bhraka Sam agaun Gurja Ransi Hukam Syalpakha Kunjo Thoche W LeteE S T Manang E R N Chokhawang Kanda Narachyang Sankh Shova Chhekam par Kol Bagarchhap Pisang Kuinem angale Marwang Taksera Prok Dana Bihi Lulang Chim khola -

K'n Dxfzfvf ;"Rgf G+= !#÷)&!÷&@ Ldlt @)&@÷)@÷)!

g]kfn ;/sf/ ef}lts k"jf{wf/ tyf oftfoft dGqfno ;8s ljefu k'n dxfzfvf ;"rgf g+= !#÷)&!÷&@ ldlt @)&@÷)@÷)! Request for Proposal k'nx?sf] lj:t[t ;e{]If0f tyf l8hfOg, O{li6d]6 tof/ ug{, o; dxfzfvfsf] EOI ;"rgf g+= )!÷)&!÷&@ ;8s ljefusf ] Website www.dor.gov.np tyf g]kfn ;dfrf/ kqdf ;"rgf k|sflzt ul/ dfu ul/Psf] Expression of Interest (EOI) cg';f/ k|fKt x'g cfPsf EOI x? ;fj{hlgs vl/b P]g, @)^# sf] bkmf #) adf]lhd Packaging ;lxtsf] ;"lr tof/ ul/ ;f]xL P]gsf] bkmf #! adf]lhd Technical & Financial Proposal ;lxtsf] Request for Proposal (RFP) oflGqs tflnd s]Gb| kl/;/, kf6g9f]sf af6 k|fKt ug{ ;lsg] 5 / #) -lt;_ lbg -@)&@÷)@÷#)_ leq a'emfpg' kg{]5 . pk/f]Qm RFP ;8s ljefusf] Website www.dor.gov.np af6 klg Download u/L Submit ug{ ;lsg] Joxf]/f ;DalGwt ;a}sf] hfgsf/Lsf] nflu of] ;"rgf k|sflzt ul/Psf] 5 . ;fy} pk/f]Qm ljj/0f oflGqs tflnd s]Gb| cjl:yt o; dxfzfvfsf] ;"rgf kf6Ldf klg 6fFl;Psf] 5 . pk–dxflgb{]zs Pkg No. BB-159-DSD-071/72-01 S. No. Firms Name 1 Multi Disciplinary Consultant (P) Ltd JV Multi Lab (P) Ltd, Kupondole Lalitpur Engineering support Consult (P) Ltd JV Design engineering consultant (P) Ltd & Bangalamukhi Engineering 2 (P) Ltd, Shantinagar Kathmandu 3 Full Bright Consultancy (P) Ltd, Sinamangal Kathmandu 4 TMS JV CARD Consult, Kamalpokhari Kathmandu 5 Welink Consultant (P) Ltd & Mass Consultant (P) Ltd JV, Kathmandu 6 Sitara Consultant (P) Ltd JV & R& R Eng. -

35173-015: Urban Water Supply and Sanitation (Sector) Project

Initial Environmental Examination _ Document Stage: Final Project Number: 35173-015 February 2019 NEP: Urban Water Supply and Sanitation (Sector) Project – Liwang (Rolpa District) Water Supply and Sanitation Subproject Package No: W-06 Prepared by Ministry of Water Supply, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This final initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. IEE of LiwangUrban Water Supply and Sanitation Project Initial Environmental Examination February 2019 NEP: Urban Water Supply and Sanitation (Sector) Project (UWSSP) Liwang Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project Rolpa, Rolpa District Prepared by the Ministry of Water Supply (MoWS) for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DCC District Coordination Committee DED Detailed Engineering Design DRTAC Design Review and Technical Audit Consultant DSC Design and Supervision Consultant DSMC Design, Supervision and Management Consultant DWSSM Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Management EARF Environmental -

Western Nepal Conflict Assessment

WESTERN NEPAL CONFLICT ASSESSMENT INTRODUCTION In March 2003, the international non-governmental organization Mercy Corps engaged the author to conduct an independent field-based assessment of the civil conflict in rural Nepal. Based in Portland, Oregon and Edinburgh, Scotland, one of Mercy Corps’ principal objectives is to assist war-torn societies with emergency relief, rehabilitation and post-conflict reconstruction. The assessment was financed by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development and was overseen by USAID Administrator Andrew Natsios. Since a relatively modest beginning in early 1996, an armed insurgency against the government by the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (hereinafter ‘the Maoists’) has, to varying degrees, gradually affected most of the country. The assessment focused on Nepal’s most acutely affected mid-western region, including the districts of Rolpa and Rukum, which are considered the Maoist insurgency’s heartland, and included field work in four other nearby districts. This area is sometimes called the Rapti River Valley after the river which flows along its southern border (see Map D) and its tributaries. The assessment’s mandate was to address: ! the root causes of the conflict; ! why the insurgency had taken root specifically in Rolpa and Rukum; ! the intersection of development programs (including a major USAID effort in the mid-western region in the 1980s and 1990s) with the conflict’s origins; ! the conduct of the insurgency by the Maoist movement, including its administration -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100 -

Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra Butyracea) in Nepal

Micro Enterprise Development Programme - MEDEP GON/MOICS/UNDP – NEP/08/006 Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra butyracea) in Nepal Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) Kathmandu, Nepal June 2010 Copyright © 2010 Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) UNDP/Ministry of Industry, Government of Nepal Bakhundole, Lalitpur PO Box 815 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel +975-2-322900 Fax +975-2-322649 Website: www.medep.org.np Author Surendra Raj Joshi Reproduction This publication may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form without permission from the copyright holder, except for educational or nonprofit purposes, provided an acknowledgment of the source is made and a copy provided to Micro-enterprise Department Programme. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of MEDEP or the Ministry of Industry. The information contained in this publication has been derived from sources believed to be reliable. However, no representation or warranty is given in respect of its accuracy, completeness or reliability. MEDEP does not accept liability for any consequences/loss due to use of the content of this publication. Note on the use of the terms: Aesandra butyracea is known by various names; Indian butter tree, Nepal butter tree, butter tree. In Nepali soe say Chyuri ad others say Chiuri. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was carried out within the overall framework of the Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) with an objective to identify the geographical and ecological coverage of Chyuri tree, and to estimate the resource potentiality for establishment of enterprises.