Why Studying Chinese Made a Difference By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy Edited by John Makeham, Australian National University VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/mcp. The Discovery of Chinese Logic By Joachim Kurtz LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kurtz, Joachim. The discovery of Chinese logic / by Joachim Kurtz. p. cm. — (Modern Chinese philosophy, ISSN 1875-9386 ; v. 1) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17338-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Logic—China—History. I. Title. II. Series. BC39.5.C47K87 2011 160.951—dc23 2011018902 ISSN 1875-9386 ISBN 978 90 04 17338 5 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................. -

The Making of China's Peace with Japan

The Making of China’s Peace with Japan Mayumi Itoh The Making of China’s Peace with Japan What Xi Jinping Should Learn from Zhou Enlai Mayumi Itoh Princeton New Jersey, USA ISBN 978-981-10-4007-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4008-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-4008-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939730 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- tional affiliations. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography

Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography Edited by May Holdsworth and Christopher Munn Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2012 ISBN 978-988-8083-66-4 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication my be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Company Limited, Hong Kong, China Hong Kong University Press is grateful to the following for their generous support of this project: The Bank of East Asia Ltd T. H. Chan Publication Fund The Croucher Foundation Edko Films Ltd Gordon & Anna Pan Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch Shun Hing Education & Charity Fund Ltd Dr Sze Nien Dak University Grants Committee of the Hong Kong SAR Editorial Board Elizabeth Sinn (Chair) May Holdsworth Joseph Ting John M. Carroll Christine Loh Y.C. Wan Chan Wai Kwan Bernard Luk Wang Gungwu Peter Cunich Christopher Munn Yip Hon Ming Colin Day Carl T. Smith Picture Editor Ko Tim Keung Contributors Shiona M. Airlie Cornelia ‘Nelly’ Lichauco Fung Norman J. Miners Hugh D.R. Baker Richard Garrett Christopher Munn Tony Banham Valery Garrett Ng Chun Hung Ruy Barretto Leo F. Goodstadt Sandy Ng Bert Becker Judith Green Robert Nield Jasper Becker Peter Halliday Timothy O’Connell Gillian Bickley Peter E. -

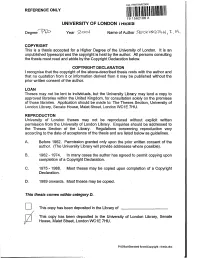

University of London Ihesis

19 1562106X UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IHESIS DegreeT^D^ Year2o o\ Name of Author5&<Z <2 (NQ-To N , T. COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTON University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

The Collar Revolution: Everyday Clothing in Guangdong As Resistance in the Cultural Revolution* Peidong Sun†

773 The Collar Revolution: Everyday Clothing in Guangdong as Resistance in the Cultural Revolution* Peidong Sun† Abstract Scholars have paid little attention to Maoist forces and legacies, and espe- cially to the influences of Maoism on people’s everyday dress habits during the Cultural Revolution. This article proposes that people’s everyday cloth- ing during that time – a period that has often been regarded as the climax of homogenization and asceticism – became a means of resistance and expres- sion. This article shows how during the Cultural Revolution people dressed to express resistance, whether intentionally or unintentionally, and to reflect their motivations, social class, gender and region. Drawing on oral histories collected from 65 people who experienced the Cultural Revolution and a large number of photographs taken during that period, the author aims to trace the historical source of fashion from the end of the 1970s to the 1980s in Guangdong province. In so doing, the author responds to theories of socialist state discipline, everyday cultural resistance, individualism and the nature of resistance under Mao’s regime. Keywords: clothing; dress resistance; the Cultural Revolution; Guangdong After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Maoist regime intervened deeply in the everyday life of Chinese people, especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). This paper examines everyday clothing practices in China during the “ten year chaos”–an area that has received little scholarly scrutiny despite the fact that dress is one of the most notable forms of cultural expression. Although it has been argued that the Cultural Revolution “froze fashion by increasing the desire to conform” in many cultural domains,1 I maintain instead that it increased people’s desire to resist, giving expression to diversity, individuality, gender distinction and geographical fusion. -

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry

PRESENTS AI WEIWEI: NEVER SORRY A FILM BY ALISON KLAYMAN FESTIVALS: 2012 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL 2012 MIAMI INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2012 INTERNATIONALE FILMFESTPIELE BERLIN 2012 TRUE/FALSE FILM FESTIVAL 2012 FULL FRAME DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL 2012 HUMAN RIGHTS FILM FESTIVAL 2012 SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2012 HOT DOCS FILM FESTIVAL 2012 INDEPENDENT FILM FESTIVAL BOSTON 2012 DOXA DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL USA / 2012 / 91 MIN. / COLOR DISTRIBUTION CONTACT: NY PRESS CONTACT: LA PRESS CONTACT: LAUREN SCHWARTZ/KIM BARRETT SUSAN NORGET/CHARLIE OLSKY FREDELL POGODIN/JONATHAN SMITH SUNDANCE SELECTS SUSAN NORGET FILM PROMOTION FREDELL POGODIN & ASSOCIATES PUBLICITY/MARKETING 198 Sixth Ave. #1 7223 Beverly Boulevard #202 11 Penn Plaza, 18th Floor New York, NY 10013 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10001 T: 212.431.0090 (323) 931-7300 T: 646.273.7214 [email protected] [email protected] F: 646.273.7250 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.ifcfilms.com For images please visit our extranet: www.ifcfilmsextranet.com (login: ifcguest01, password: kubrick; select “AI WEIWEI: NEVER SORRY” from the drop-down bar) SYNOPSIS Named by ArtReview as the most powerful artist in the world, Ai Weiwei is China's most celebrated contemporary artist, and its most outspoken domestic critic. In April 2011, when Ai disappeared into police custody for three months he quickly became China’s most famous missing person, having first risen to international prominence in 2008 after helping design Beijing’s iconic Bird’s Nest Olympic Stadium-and then publicly denouncing the Games as party propaganda. Since then, Ai Weiwei’s critiques of China’s repressive regime have ranged from playful photographs of his raised middle finger in front of Tiananmen Square to searing memorials to the more than 5,000 schoolchildren who died in shoddy government construction in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. -

H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. X, No. 22 (2009)

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Volume X, No. 22 (2009) 8 July 2009 Chaozhu Ji. The Man on Mao’s Right: From Harvard Yard to Tiananmen Square, My Life inside China’s Foreign Ministry. New York: Random House, 2008. 336p. ISBN 9781400065844 (alk. paper). $28.00. Roundtable Editors: Yafeng Xia and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Introduction by Yafeng Xia Reviewers: James Z. Gao, Charles W. Hayford, Lorenz M. Lüthi, Raymond P. Ojserkis, Priscilla Roberts, Patrick Fuliang Shan, Qiang Zhai. Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-22.pdf Contents Introduction by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University .................................................................. 2 Review by James Z. Gao, University of Maryland at College Park ............................................ 7 Review by Charles Hayford, Northwestern University ............................................................. 9 Review by Lorenz M. Lüthi, McGill University ........................................................................ 18 Review by Raymond P. Ojserkis, Rutgers University Newark ................................................. 21 Review by Patrick Fuliang Shan, Grand Valley State University ............................................. 26 Review by Priscilla Roberts, The University of Hong Kong ..................................................... 30 Review by Qiang Zhai, Auburn University Montgomery ........................................................ 39 Copyright © -

China Council Quarterly 4110 SE Hawthorne Blvd

Jan - Mar 2021 - Issue 147 China Council Quarterly 4110 SE Hawthorne Blvd. #128, Portland OR 97214 www.nwchina.org LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT If you enjoy Chinese films, Michael Bloom and Shireen Farrahi have done a wonderful job programming and In my front yard and yards hosting a monthly slate of notable, easily accessible Chi- across my neighborhood I’m nese films to watch then discuss virtually. You watch the seeing beautiful purple crocus film at your own leisure online, then join a virtual discus- flowers blooming. A welcome sion about the film. When possible, experts in the sub- sign of spring - of hope. jects portrayed in the film join in on the discussion. Look for announcements about upcoming films in your email. The last in-person Northwest China Council board meeting - As always, I want to thank each of you for your ongoing or event of any kind was held support in these times. The entire Northwest China Coun- over a year ago, in February of cil board and I truly appreciate it. 2020. At that time, the coronavirus was part of our con- versation, but it was still an ocean away. Since then, Stay safe, Joe Liston we’ve tried to chart a path through the uncertainty for not only the Northwest China Council, but for our MANDARIN CHINESE CLASSES families, businesses and ourselves. It hasn’t been easy and hope has been tough to find at times. Chinese Language Classes Spring With our state in the process of vaccinating the popula- tion, we finally can see blossoms of hope. -

![Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[On-Going] (Bulk 1970-1995)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0453/him-mark-lai-papers-1778-on-going-bulk-1970-1995-5480453.webp)

Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[On-Going] (Bulk 1970-1995)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7r29q3gq No online items Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Processed by Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Yu Li, Janice Otani, Limin Fu, Yen Chen, Joy Hung, Lin Lin Ma, Zhuqing Xia and Mabel Yang The Ethnic Studies Library. 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai AAS ARC 2000/80 1 Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Collection number: AAS ARC 2000/80 The Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Ethnic Studies Library. 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu/ Collection Processed By: Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Yu Li, Janice Otani, Limin Fu, Yen Chen, Joy Hung, Lin Lin Ma, Zhuqing Xia and Mabel Yang Date Completed: May 2003 Finding Aid written by: Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Janice Otani and Wei Chi Poon © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Him Mark Lai Papers, Date: 1778-[on-going] Date (bulk): (bulk 1970-1995) Collection number: AAS ARC 2000/80 Creator: Lai, H. Mark Extent: 130 Cartons, 61 Boxes, 7 Oversize Folders199.4 linear feet Repository: University of California, BerkeleyThe Ethnic Studies Library Berkeley, California 94720-2360 Abstract: The Him Mark Lai Papers are divided into four series: Research Files, Professional Activities, Writings, and Personal Papers. -

October 21, 1975 Memorandum of Conversation Between Mao Zedong and Henry A

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 21, 1975 Memorandum of Conversation between Mao Zedong and Henry A. Kissinger Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Mao Zedong and Henry A. Kissinger,” October 21, 1975, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, National Security Adviser Trip Briefing Books and Cables for President Ford, 1974-1976 (Box 19). http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118072 Summary: U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met Chairman Mao at his residence in Peking. The two argued about the importance of U.S.-Chinese relations in American politics. Mao repeats that the United States' concerns order America, the Soviet Union, Europe, Japan, and lastly China. Kissinger responds that the Soviet Union, as a superpower, is frequently dealt with, but in strategy China is a priority. Throughout the conversation, Mao continues to point out his old age and failing health. The leaders also discuss European unity, Japanese hegemony, German reunification, and the New York Times. Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription Scan of Original Document SECRET/SENSITTVE MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: Chairman Mao Tse-tung [Mao Zedong] Teng Hsiao-p'ing [Deng Xiaoping], Vice Premier of the State Council of the People's Republic of China Ch'iao Kuan-hua [Qiao Guanhua], Minister of Foreign Affairs Amb. Huang Chen [Huang Zhen], Chief of PRC Liaison Office, Washington Wang Hai-jung [Wang Hairong], Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs T'ang Wen-sheng [Tang Wensheng], Deputy Director, Department of American and Oceanic Affairs and interpreter Chang Han-chih [Zhang Hanzhi], Deputy Director, Department of American and Oceanic Affairs Dr. -

Three Chinese Characters Liu Hongbin, Word Conjurer, Smuggler of Nightmares

Three Chinese Characters Liu Hongbin, Word Conjurer, Smuggler of Nightmares Such news as I have, which is to say within the time of this prose, is that the poet Liu Hongbin has gone into seclusion. Whether for spiritual exercises or in order to write or to further immerse himself in 2,000 years of Chinese literature he won’t say, but it is perfectly conceivable that it’s a combination of all three. Soon after he arrived here, in 1989, swinging wildly between despair and hope, he declared that what the contemporary Chinese poet must seek to do is build ‘a historical bridge between the glory of Chinese classical poetry and the ruins of modern Chinese language.’ An older, humbler, Hongbin finds such words, when mirrored back at him, pompous in the extreme and yet they do not come out of nowhere. As a child during the Cultural Revolution he witnessed the most extreme self-desecration of any single culture, when the great classics were thrown to the flames, temples destroyed, antiquities smashed, teachers beaten to death, often by their own students, and censorship so extreme as to be barely censorship at all but rather a monitoring of the flickering of one’s neighbour’s eyelashes. All this was at a time when elsewhere in the world university students clutching their translations of Mao’s Little Red Book spoke blithely of its author as having done what needed to be done. The day before we spoke, Hongbin walked to a nearby internet café in order to check his messages when a well-dressed woman, clearly troubled, sat down opposite him, asked him who he was, and when he smiled back at her she said, ‘Do you think I’m rubbish?’ Hongbin pointed to a vase of flowers on his table and told her how beautiful they were.