Canepa-The Iranian Expanse.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study the Status Column Element in the Achaemenid Architecture and Its

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND January 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Study the status column element in the Achaemenid architecture and its effect on India architecture (comparrative research of persepolis columns on pataly putra columns in India) Dr. Amir Akbari* Faculty of History, Bojnourd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bojnourd, Iran * Corresponding Author Fariba Amini Department of Architecture, Bukan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bukan, Iran Elham Jafari Department of Architecture, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran Abstract In the southern region of Iran and the north of persian Gulf, the state was located in the ancient times was called "pars", since the beginning of the Islamic era its center was shiraz. In this region of Iran a dynasty called Achaemenid came to power and could govern on the very important part of the worlds for years. Achaemenid exploited the skills of artists and craftsman countries under its command. In this sense, in Architecture works and the industry this period is been seen the influence of other nations. Achaemenid kings started to build large and beautiful palaces in the unter of their government and after 25 centuries, the remnants of which still remain firm and after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire by Grecian Alexander in India. The greatest king of India dynasty Muryya, was called Ashoka the grands of Chandra Gupta. The Ashoka palace that id located at the putra pataly around panta town in the state of Bihar in North east India. Is an evidence of the influence of Achaemenid culture in ancient India. The similarity of this city and Ashoka Hall with Apadana Hall in Persepolis in such way that has called it a india persepolis set. -

Iranian Coins & Mints: Achaemenid Dynasty

IRANIAN COINS & MINTS: ACHAEMENID DYNASTY DARIC The Achaemenid Currency By: Michael Alram DARIC (Gk. dareiko‚s statê´r), Achaemenid gold coin of ca. 8.4 gr, which was introduced by Darius I the Great (q.v.; 522-486 B.C.E.) toward the end of the 6th century B.C.E. The daric and the similar silver coin, the siglos (Gk. síglos mediko‚s), represented the bimetallic monetary standard that the Achaemenids developed from that of the Lydians (Herodotus, 1.94). Although it was the only gold coin of its period that was struck continuously, the daric was eventually displaced from its central economic position first by the biga stater of Philip II of Macedonia (359-36 B.C.E.) and then, conclusively, by the Nike stater of Alexander II of Macedonia (336-23 B.C.E.). The ancient Greeks believed that the term dareiko‚s was derived from the name of Darius the Great (Pollux, Onomastikon 3.87, 7.98; cf. Caccamo Caltabiano and Radici Colace), who was believed to have introduced these coins. For example, Herodotus reported that Darius had struck coins of pure gold (4.166, 7.28: chrysíou statê´rôn Dareikôn). On the other hand, modern scholars have generally supposed that the Greek term dareiko‚s can be traced back to Old Persian *dari- "golden" and that it was first associated with the name of Darius only in later folk etymology (Herzfeld, p. 146; for the contrary view, see Bivar, p. 621; DARIUS iii). During the 5th century B.C.E. the term dareiko‚s was generally and exclusively used to designate Persian coins, which were circulating so widely among the Greeks that in popular speech they were dubbed toxo‚tai "archers" after the image of the figure with a bow that appeared on them (Plutarch, Artoxerxes 20.4; idem, Agesilaus 15.6). -

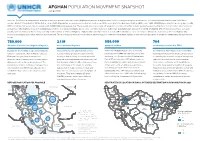

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

The Political Thought of Darius the Great (522- 486 B.C.), the Legislator of Achaemenid Empire (A Study Based on Achaemenid Inscriptions in Old Persian)

International Journal of Political Science ISSN: 2228-6217 Vol.3, No.6, Spring 2013, (pp.51-65) The Political Thought of Darius the Great (522- 486 B.C.), the Legislator of Achaemenid Empire (A Study Based on Achaemenid Inscriptions in Old Persian) Awat Abbasi* Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies Received: 5 Dec 2012 ; Accepted: 11 Feb 2013 Abstract: Darius offered the political order of “king of kings” to solve the political crisis of his era. He legitimized it based on an order of gods. In his belief, the nature of politics was based on a dualis- tic religious worldview that is the fight between true divinity and false divinity’s will and perfor- mance in the world. In addition, the chief true divinity’s law was introduced as the principle order in the world and eternal happiness in true divinity’s house. Therefore, it was considered as the pattern of political order following which was propagandized as the way to reach happiness in this world and salvation in next life. To protect this law, the chief true divinity bestowed the political power to the ruler. Therefore, what should be the political order and who should be the ruler, is justified in the context of the definitions of human, world, happiness and salvation. The sovereignty of the ruler and, therefore, the domination of the chief true divinity’s laws in politics were considered as justice. This definition of justice denied liberty and promoted absolutism. In justifying the ruler’s absolute power, even his laws and commands were considered as the dominant norms over the politics. -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Zoroastrian Elements in the Syncretism That Prevailed in Asia Minor Following the Achaemenian Conquests KERSEY H

Zoroastrian Elements in the Syncretism that Prevailed in Asia Minor Following the Achaemenian Conquests KERSEY H. ANTIA Introduction Since the total population of Zoroastrians in the entire world today is a meager 130,000 at best, it is hard to conceive that Zoroastrianism not only prospered in Iran but also acted as a very prominent factor in the syncretism that prevailed in Asia Minor from the time it became an integral part of the Achaemenian empire to the downfall of the Sasanian empire. It is generally acknowledged that Semitic Armenia was Persianised in the Achaemenian times, a process which lasted up to the Sasanian times. Strabo. (XI.532) reports that Mithra and Anahita were especially worshiped by the Armenians. It was also in the Achaemenian times that the Jews first came into contact with the Persians. The Zoroastrian concepts heretofore unknown to the Jews such as satan, “the angel of wisdom”, and “the holy spirit” became common features of Jewish beliefs, along with many others. Moreover, the Achaemenian kings welcomed Greek scientists, physicians and Phoenician explorers and artisans at their courts. The conquest of Iran by Alexander the Great further exposed the Greeks to Iranian influence just as it exposed Iran to Greek Influence. Alexander married an Iranian princess, Roxane and he arranged for a mass marriage of 50,000 of his Greek soldiers with Iranian women at Susa after his return from India. Such a mass phenomenon must have left its mark on the fusion of the two races. With the Greeks came their gods represented in human forms, a concept so sacrilegious to the Iranians. -

Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire

4/12/2012 Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire HIST 213 Spring 2012 Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) Successors of the Achaemenids 224 CE Ardashir I • a descendant of Sasan – gave his name to the new Sasanian dynasty, • defeated the Parthians • The Sasanians saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians. 1 4/12/2012 Shapur I (r. 241–72 CE) • One of the most energetic and able Sasanian rulers • the central government was strengthened • the coinage was reformed • Zoroastrianism was made the state religion • The expansion of Sasanian power in the west brought conflict with Rome Shapur I the Conqueror • conquers Bactria and Kushan in east • led several campaigns against Rome in west Penetrating deep into Eastern-Roman territory • conquered Antiochia (253 or 256) Defeated the Roman emperors: • Gordian III (238–244) • Philip the Arab (244–249) • Valerian (253–260) – 259 Valerian taken into captivity after the Battle of Edessa – disgrace for the Romans • Shapur I celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam. Rome defeated in battle Relief of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam, showing the two defeated Roman Emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab 2 4/12/2012 Terry Jones, Barbarians (BBC 2006) clip 1=9:00 to end clip 2 start - … • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_WqUbp RChU&feature=related • http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&featu re=endscreen&v=QxS6V3lc6vM Shapur I Religiously Tolerant Intensive development plans • founded many cities, some settled in part by Roman emigrants. – included Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sasanian rule • Shapur I particularly favored Manichaeism – He protected Mani and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad • Shapur I befriends Babylonian rabbi Shmuel – This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Considering the Failures of the Parthians Against the Invasions of the Central Asian Tribal Confederations in the 120S Bce

NIKOLAUS OVERTOOM WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY CONSIDERING THE FAILURES OF THE PARTHIANS AGAINST THE INVASIONS OF THE CENTRAL ASIAN TRIBAL CONFEDERATIONS IN THE 120S BCE SUMMARY When the Parthians rebelled against the Seleucid Empire in the middle third century BCE, seizing a large section of northeastern Iran, they inherited the challenging responsibility of monitoring the extensive frontier between the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppe. Although initially able to maintain working relations with various tribal confederations in the region, with the final collapse of the Bactrian kingdom in the 130s BCE, the ever-wide- ning eastern frontier of the Parthian state became increasingly unstable, and in the 120s BCE nomadic warriors devastated the vulnerable eastern territories of the Parthian state, temporarily eliminating Parthian control of the Iranian plateau. This article is a conside- ration of the failures of the Parthians to meet and overcome the obstacles they faced along their eastern frontier in the 120s BCE and a reevaluation of the causes and consequences of the events. It concludes that western distractions and the mismanagement of eastern affairs by the Arsacids turned a minor dispute into one of the most costly and difficult struggles in Parthian history. Key-words: history; Parthians; Seleucids; Central Asia; nomads; frontiers. RÉSUMÉ Lorsque, au milieu du IIIe siècle av. J.-C., les Parthes se rebellèrent contre l’État séleucide en s’emparant d’une grande partie du nord-est de l’Iran, ils héritèrent de la tâche difficile -

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media Author(s): Farhang Khademi Nadooshan, Seyed Sadrudin Moosavi, Frouzandeh Jafarzadeh Pour Reviewed work(s): Source: Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 68, No. 3, Archaeology in Iran (Sep., 2005), pp. 123-127 Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067611 . Accessed: 06/11/2011 07:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Near Eastern Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org The Parthians (174 BCE-224CE) suc- , The coins discussed here are primarily from ceeded in the the Lorestan Museum, which houses the establishing longest jyj^' in the ancient coins of southern Media.1 However, lasting empire J0^%^ 1 Near East.At its Parthian JF the coins of northern Media are also height, ^S^ considered thanks to the collection ruleextended Anatolia to M from ^^^/;. housed in the Azerbaijan Museum theIndus and the Valley from Ef-'?S&f?'''' in the city of Tabriz. Most of the Sea to the Persian m Caspian ^^^/// coins of the Azerbaijan Museum Farhang Khademi Gulf Consummate horsemen el /?/ have been donated by local ^^ i Nadooshan, Seyed indigenoustoCentral Asia, the ? people and have been reported ?| ?????J SadrudinMoosavi, Parthians achieved fame for Is u1 and documented in their names. -

Elbrus 5642M (South) - Russia

Elbrus 5642m (South) - Russia & Damavand 5671m - Iran EXPEDITION OVERVIEW Mount Elbrus and Mount Damavand Combo In just two weeks this combo expedition takes you to the volcanoes of Damavand in Iran, which is Asia’s highest, and Elbrus in Russia, which is Europe’s highest. On Elbrus we gradually gain height and increase our chance of success by taking time to acclimatise in the Syltran-Su valley on Mount Mukal, which offers views across the beautiful valleys to Elbrus. Once acclimatised, we climb these sweeping snow slopes to the col between Elbrus’ twin summits before continuing easily to the true summit of Europe’s highest mountain in an ascent of about 1000m. A brief celebration and then we fly direct to Tehran where Mount Damavand may be little known outside its home nation of Iran but it is Asia’s highest volcano and provides a delightful challenge for mountaineers. It is located northeast of Tehran, close to the Caspian Sea and dominates the Alborz mountain range. Damavand is, with its near-symmetrical lines, a beautiful and graceful peak that has lain dormant for 10,000 years. On reaching the crater rim you walk around it to the true summit and it is possible to walk into the crater. It is technically easy but demands a good level of fitness. PLEASE NOTE – YOU WILL NEED TO BOOK THIS TRIP AT LEAST 3 MONTHS BEFORE THE DEPARTURE DATE, TO ALLOW TIME TO GET YOUR AUTHORISATION CODE AND VISA FOR IRAN. The Volcanic Seven Summits Challenge – your dream met, a worldwide journey to the seven continents with a unique challenge that has only been completed by a handful of people.