Aspasia and Cleopatra Metrodora, Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theodora, Aetius of Amida, and Procopius: Some Possible Connections John Scarborough

Theodora, Aetius of Amida, and Procopius: Some Possible Connections John Scarborough HEN ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL SOURCES speak of prostitutes’ expertise, they frequently address the Wquestion of how they managed to keep free from pregnancies. Anyone unschooled in botanicals that were con- traceptives or abortifacients might pose a question similar to that of an anonymous writer in twelfth-century Salerno who asks medical students: “As prostitutes have very frequent intercourse, why do they conceive only rarely?”1 Procopius’ infamous invective, describing the young Theodora’s skills in prostitution, contains a similar phrase: she “became pregnant in numerous instances, but almost always could expel instantly the results of her coupling.”2 Neither text specifies the manner of abortion or contraception, probably similar to those re- corded in the second century by Soranus of Ephesus (see be- low). Procopius’ deliciously scandalous narrative is questionable 1 Brian Lawn, The Prose Salernitan Questions (London 1970) B 10 (p.6): Que- ritur cum prostitute meretrices frequentissime coeant, unde accidat quod raro concipiant? 2 Procop. Anec. 9.19 (ed. Haury): καὶ συχνὰ µὲν ἐκύει, πάντα δὲ σχεδὸν τεχνάζουσα ἐξαµβλίσκειν εὐθὺς ἴσχυε, which can also be translated “She conceived frequently, but since she used quickly all known drugs, a mis- carriage was effected”; if τεχνάζουσα is the ‘application of a specialized skill’, the implication becomes she employed drugs that were abortifacients. Other passages suggestive of Procopius’ interests in medicine and surgery include Wars 2.22–23 (the plague, adapted from Thucydides’ description of the plague at Athens, with the added ‘buboes’ of Bubonic Plague, and an account of autopsies performed by physicians on plague victims), 6.2.14–18 (military medicine and surgery), and 1.16.7 (the infamous description of how the Persians blinded malefactors, reported matter-of-factly). -

CUHSLROG M105.Pdf (3.596Mb)

Dec 71 ARABIC MEDICINE Selected Readings Campbell D: Arabian medicine and its influence on the middle ages. (Vol. 1) WZ 70 Cl 87a 1926 Withington ET: Medical history from the earliest times. (reprint of 1894 edition) pp. 138-175 WZ 40 W824m 1964 Neuberger M: History of medicine. pp. 344-394 WZ 40 N478P 1910 Browne EG: Arabian medicine, being the Fitzpatrick Lectures delivered at the Royal College of Physicians in November 1919 and November 192 0. WZ 51 B882a 1921 Elgood C: A medical history of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate from the earliest times until the year A. D. 1932. WZ 70 E41m 1951 Levey M: The medical formulary of Al-Samarqandi. QV 11 A165L 1967 Avicenna: Poem on medicine. WZ 220 A957K 1963 Rhazes: A treatise on the smallpox and measles. Tr. by W. A. Greenhill WZ 220 R468t 1848 (does not circulate) Maimonides: Two treatises on the regimen of health. WZ 220 M223B 1964 ~~"~ _______......W::..:..::Z..:....:~'---<vf,__L._4___..,;vJ......c..h~-----=--rt:i7-- ;J:o /t. a._:_J .:....::t ei:____ _________ ~---lfHrbl-~s--+- -~-'---+ --+----'--- ✓ /~~----------------+- ~ M.,( S~ l AVENZOAR 1113-1162 Born and died at Se ville. He was opposed to astrology and medical mysticism; he was a gainst the use of sophistical subtleties in the practice of medicine. His principal work is the Altersir, in which he mentions the itch-mite, and describes operations for renal calculus and for tracheotomy. 11 His memory remains that of a truly great practitioner, whose voice fell upon the deaf ears of his contemporaries and successors, but whose achievements herelded a new era of medicine free from subservience to authority. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Role of Albucasis in Evolution of the History of Otorhinolaryngology

Global Journal of Otolaryngology ISSN 2474-7556 Research Article Glob J Otolaryngol Volume 2 Issue 4 - December 2016 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Faisal Dibsi DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2016.02.555593 The Role of Albucasis in Evolution of the History of Otorhinolaryngology Faisal Dibsi* Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, AL AHAHBA Private University, Aleppo City, Syria Submission: September 29, 2016; Published: December 15, 2016 *Corresponding author: Faisal Dibsi, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, AL-KALIMAT HOSPITAL, Al-Sabil Area, Rezq-Allah Tahan Street, P.O.Box: 862, Aleppo city - Syria, Tel: 00963 21 2645909/00963944 488980; Email: Abstract comprising his Kitab al-Tasrif li-man ajiza an al-Taʹalif, the excellent surgical textbook with illustration of surgical instruments in the Middle Ages.“ALBUCASIS Most of the (936-1013 content was AD) a author repetition the first of the rational, earlier complete, contributions and illustrated of Paul Aegina treatises (7 thof surgery. The Surgery is the last of thirty treatises translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona (12th and practical surgeon. This surgical textbook describes many operative procedures, manipulations Century) and with instruments modifications. in Otorhinolaryngology, This textbook was explained the suture of new and old wounds in the Century) Nose, Lip, and and greatly Ear. In influenced the Ear Diseases Europe include as Eastern removing Islamic foreign countries. bodies, He performing was a working operations doctor for obstruction of the ear because of congenital aural atresia, scars and stenosis after injuries, polyps and granulations, extraction a creatures. Forward the Nose Diseases treatment fractures, nasal fistula, nasal polyps and tumors. -

Rodrigo De Castro's Portrait of the Perfect Physician in Early

Medical Ideals in the Sephardic Diaspora: Rodrigo de Castro’s Portrait of the Perfect Physician in early Seventeenth-Century Hamburg JON ARRIZABALAGA Introduction As is well known, there were no formal systems of medical ethics until the end of the eighteenth century. Yet at least from the composition of the Hippocratic Oath, western scholarly debates, particularly among doctors, on the foundations of good medical practice and behaviour produced written works. These works simultaneously reflected and con- tributed to setting customary rules of collective behaviour—medical etiquette—that were reinforced by pressure groups who, while they could not always judge and sentence offenders, sanctioned them with disapproval. Most early modern works on medical etiquette were dominated by the question of what constituted a good medical practitioner, with the emphasis sometimes on the most suitable character of a physician, sometimes on professional behaviour.1 The medical literary genre of the perfect physician appears to have been popular in the early modern Iberian world, and the frequent involvement of converso practitioners in writing about it has often been associated with the peculiarities of their professional posi- tion in the territories under the Spanish monarchy.2 Among the most outstanding examples This article has been prepared within the framework of the research project BHA2002-00512 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology. I am indebted to Enrique Cantera Montenegro, Andrew Cunningham, Teresa Huguet-Termes and Sebastia` Giralt for their advice and material assistance. 1 See the entry ‘Medical ethics, history of Europe’, particularly the sections ‘Ancient and medieval’ (by Darrel W Amundsen) and ‘Renaissance and Enlightenment’ (by Harold J Cook) as well as the bibliography referred to there, in Stephen G Post (ed.), Encyclopedia of bioethics, 3rd ed., 5 vols, New York, Macmillan Reference USA, 2004, vol. -

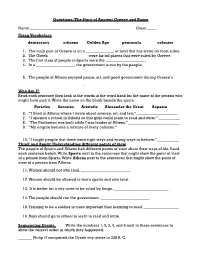

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

Surgery on Varices in Byzantine Times (324-1453 CE)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORICAL REVIEW Surgery on varices in Byzantine times (324-1453 CE) John Lascaratos, MD, PhD,a Christos Liapis, MD,b and Maria Kouvaraki, MD,b Athens, Greece Objectives: The purposes of this article are to describe Byzantine varicose vein surgery and to note its influence on the devel- opment of these operations after that time. A study and analysis of the original texts of the Byzantine physicians, written in Greek and containing the now mostly lost knowledge of the earlier Hellenistic and Roman periods, was undertaken. Results: The Byzantines paid special attention to varicosis surgery from the early period of the empire. The famous fourth-century (CE) physician Oribasius meticulously described a number of surgical methods of confronting varicosis, some of which were derived from the texts of earlier Greek surgeons, to which he added his own keen observations. Later, eminent Byzantine physicians developed these techniques further and evaluated their usefulness. Conclusions: The study of Byzantine medical texts proves that several surgical techniques on varicosis were widely prac- ticed in Byzantine times and were derived from the work of ancient Greek and Roman physicians. The techniques described had a great influence on western medieval and later European surgery, thus constituting significant roots of modern angiology. (J Vasc Surg 2001;33:197-203.) Medical practice and surgery seem to have been highly work of the ancient Greek physician Antyllus (second cen- developed during the early Byzantine period, from the tury CE). -

Nova Et Vetera .Of the Times Recognized the Necessity of Direct Contact with the Hellenic Writings

SEPT. 1936 LINACRE AND THE SCHOLAR-PHYSICIANS OF OXFORD <THEBRITISH 550 12, MNEDICAL JOURNAL I These conditions could not endure. Arabian-taught medicine was scholastic and sterile. Powerful thinkers Nova et Vetera .of the times recognized the necessity of direct contact with the Hellenic writings. John Basingstoke, an Oxford man, travelled to Greece, and there learnt Greck THOMAS LINACRE AND THE FIRST from a learned Athenian woman, Constantina. He re- soon * turned to England with Greek manuscripts, and was SCHOLAR-PHYSICIANS OF OXFORD in contact with the great churchman and scholar Robert BY Grosseteste (1175-1253). Grosseteste's life is in large part bound up with Oxford, where he was educated. A. P. CAWADIAS, O.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P. Wishing to increase his knowledge of true science he PHYSICIAN TO TIIE ST. JOHN CLINIC AND INSTITUTE OF PHYSICAL MEDICINE studied Greek not only at second hand in Paris but at Oxford with a native Greek, Nicolas or Elicheros, and began to translate Greek authors, unfortunately not im- Thomas Linacre and Leonicenus were the greatest portant writers. His friend and Oxford contemporary, physicians of the early Renaissance. Around the former Roger Bacon, the Doctor mirabilis, with the courage radiated a group of other eminent physicians who, with and energy which characterized his whole life, pointed the exception of Caius, were all of Oxford. The studies out that the knowledge received from the Arabian writers and medical preparation of Linacre belong to the last was imperfect because of faulty translation, and he quarter of the fifteenth the period of active century; blamed the professors for not learning Greek so as to life, as in the case of the other great Oxford scholar- be able to read Aristotle and other writers in the original. -

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem.