What I Wanted to Avoid Was an Easy Equation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

E-Register: January, 2018

E-Register: January, 2018 S.No. RoC No. Date Diary No. Title of Work Category Applicant 1 L-71742/2018 01/01/2018 13984/2016-CO/L BLACK MONEY a Literary/ RAHUL PANDEY serious case of Dramatic money laundering in 2020 2 L-71743/2018 01/01/2018 9853/2016-CO/L No Kidding! Literary/ Kinjal Goyal Dramatic 3 L-71744/2018 01/01/2018 12037/2017-CO/L THE WHEEL CHAIR Literary/ Dr. Mrs. Vaishali Sanjeev Dramatic Chaudhary 4 A-122696/2018 01/01/2018 6600/2017-CO/A LATIKA Artistic LATIKA 5 L-71745/2018 01/01/2018 2671/2016-CO/L NANDA DENTAL Literary/ NANDA DENTAL CLINIC CLINIC Dramatic 6 L-71746/2018 01/01/2018 7147/2016-CO/L DHARMA Literary/ Kapur Films Dramatic 7 L-71747/2018 01/01/2018 8668/2016-CO/L Isaque Bagwan Literary/ Isaque Ibrahim Bagwan Dramatic 8 A-122697/2018 01/01/2018 5623/2016-CO/L WELCOME TO THE Artistic ALEE CLUB WORLD OF ALEE CLUB 9 L-71748/2018 01/01/2018 10146/2016-CO/L Retrograde Jupiter - Literary/ Himanshu Shangari Part I Dramatic 10 L-71749/2018 01/01/2018 10150/2016-CO/L Retrograde Venus - Literary/ Himanshu Shangari Part I Dramatic 11 A-122698/2018 01/01/2018 1379/2016-CO/A EMBOSSED ROUND Artistic SALMAN AZAM, INDIAN CUP 12 A-122699/2018 01/01/2018 1387/2016-CO/A SQUARE LOOP CHAIN Artistic SALMAN AZAM 13 A-122700/2018 01/01/2018 11268/2016-CO/A SUPER SANAT 781 Artistic SHREEDHAR BIRI WORKS BIRI LABEL PRO. -

QCA-Maharbharat in Audit

The Quintessential Chartered Accountant – Mahabharata in Audit A visit to a book store would invariably find comparable to Lord Krishna’s act of isolating ( you gazing at a myriad titles representing after eliminating) Barbarika from the battle. works set in mythological contexts. Starting The story goes that Barbarika, the son of with the The Great Indian Novel by Sashi Ghatotkacha has three arrows, one that could Tharoor to the more recent Ramayana series identify all the targets that its master would by Ashok Banker and the Shiva trilogy by wanted to destroy, the second that would Amish Tripathi, these books seem to have protect all the elements that the master caught the imagination of quite a few causing wanted to protect and the third that would them to be runaway successes. So why not destroy the first group. Lord Krishna skillfully examine Mahabharatha in the context of eliminated this warrior from the battle and modern day Audit. I have attempted to take a places his head on a mountain to witness the leaf (4 leaves to be precise) to illustrate how battle the epic with its embedded narratives is played out daily, if not every moment, in our Obsessive determination profession as well. I am not going to deny that The elections are around the corner, the I have also been influenced by Devadutt determination of the contestants can only be Patnaik of the Fortune group as well compared to Arjuna’s relentless focus in the A Play of Words archery contest to aim and achieve the fruit. The key difference here is that we have about The CARO phrase that a client is generally 40-50 Arjuna equivalents targeting us through regular in depositing PF and ESI dues is missives, messages and mailers. -

5Th Grade Syllabus 2021

5th Grade: Gagan Syllabus Core Reference Books Amar Chitra Katha Books Mahabharata (Purna Vidya Part 5) Raja Raja Chola A Children's History of India The Gita Hindi Language for Kids and Beginners Sea Route to India Monuments of India Other Reference Materials: http://www.historydiscussion.net/empires/history-of-the-gupta-empire-indian-history/600 http://www.indianmirror.com/dynasty/dynasty-home.html # Book Topic Indian History Conversational Hindi I 1 Mahabharata I Review India, it's geography and it's trade routes Introduction to Hindi 2 Udyoga Parva - UP - Krishna tells Karna of his true parentage, Kunti meets Karna, and all Introduction to Gupta Dynasty and Dynasty Lineage ( pgs. How to introduce self prepare for war 77-91 in Children's History of India) 3 Bhishma Parvaa - BP - War begins, Arjuna's grief, Bhagavad Gita & Bhishmaa's onslaught Gupta Military Organization Conversations - Sentence Structure 4 BP - Ghatotkaca destroys the Kaurava army, Arjuna battles Bhishma & other 7th day Gupta Culture and Fall of the Dynasty Pronouns and Daily events Activities 5 BP - Sikhandi breaks Bhishma's bow, Arjunaa causes the fall of Bhishma, Karnaa meets Iron Age Kingdoms (pgs. 92-109 in Children's History of Pronouns and Daily Bhismaa India) Activities continued 6 Drona Parvaa - DP - Drona devastates the Pandava army, King Bhagadatta & Supratikaa Vijayanagar Kingdom, Pallavas, Chalukyas Number and Times the elephant causes havoc of Day 7 DP - Krishnaa saves Arjuna from Vaishnava Astra, Duryodhanaa accuses Dronaa, Marathas Revision Abhimanyu -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

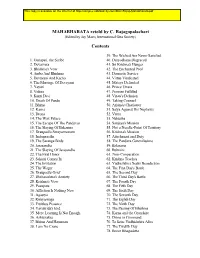

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Editors Him Chatterjee Pankaj Gupta Mritunjay Sharma Virender Kaushal

[ebook Series 1] Pratibha Spandan Editors Him Chatterjee Pankaj Gupta Mritunjay Sharma Virender Kaushal Emerging Trends in Art and Literature Emerging Trends in Art and Literature 2020 ISBN 978-81-945576-0-9 (ebook) Editors Him Chatterjee Mritunjay Sharma Pankaj Gupta Virender Kaushal Price: FREE OPEN ACCESS Published by Pratibha Spandan Long View, Jutogh, Shimla 171008 Himachal Pradesh, India. email : [email protected] website : www.pratibha-spandan.org © All rights reserved with Pratibha Spandan and authors of particular articles. This book is published open access. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical or other, including photocopy, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s), Editor(s) and the Publisher. The contributors/authors are responsible for copyright clearance for any part of the contents of their article. The opinion or views expressed in the articles are personal opinions of the contributors/authors and are in no sense official. Neither the Pratibha Spandan nor the Editor(s) are responsible for them. All disputes are subject to the jurisdiction of District courts of Shimla, Himachal Pradesh only. 2 Emerging Trends in Art and Literature Dedicated to all knowledge seekers 3 Emerging Trends in Art and Literature PREFACE Present ear is an epoch of multidisciplinary research where the people are not only working across the disciple but have been contributing to the field of academics and research. Art and Literature has been the subject of dialogue from the times of yore. -

The Panchala Maha Utsav a Tribute to the Rich Cultural Heritage of Auspicious Panchala Desha and It’S Brave Princess Draupadi

Commemorting 10years with The Panchala Maha Utsav A Tribute to the rich Cultural Heritage of auspicious Panchala Desha and It’s brave Princess Draupadi. The First of its kind Historic Celebration We Enter The Past, To Create Opportunities For The Future A Report of Proceedings Of programs from 15th -19th Dec 2013 At Dilli Haat and India International Center 2 1 Objective Panchala region is a rich repository of tangible & intangible heritage & culture and has a legacy of rich history and literature, Kampilya being a great centre for Vedic leanings. Tangible heritage is being preserved by Archaeological Survey of India (Kampilya , Ahichchetra, Sankia etc being Nationally Protected Sites). However, negligible or very little attention has been given to the intangible arts & traditions related to the Panchala history. Intangible heritage is a part of the living traditions and form a very important component of our collective cultures and traditions, as well as History. As Draupadi Trust completed 10 years on 15th Dec 2013, we celebrated our progressive woman Draupadi, and the A Master Piece titled Parvati excavated at Panchala Desha (Ahichhetra Region) during the 1940 excavation and now a prestigious display at National Museum, Rich Cultural Heritage of her historic New Delhi. Panchala Desha. We organised the “Panchaala Maha Utsav” with special Unique Features: (a) Half Moon indicating ‘Chandravanshi’ focus on the Vedic city i.e. Draupadi’s lineage from King Drupad, (b) Third Eye of Shiva, (c) Exquisite Kampilya. The main highlights of this Hairstyle (showing Draupadi’s love for her hair). MahaUtsav was the showcasing of the Culture, Crafts and other Tangible and Intangible Heritage of this rich land, which is on the banks of Ganga, this reverend land of Draupadi’s birth, land of Sage Kapil Muni, of Ayurvedic Gospel Charac Saminhita, of Buddha & Jain Tirthankaras, the land visited by Hiuen Tsang & Alexander Cunningham, and much more. -

Part 1: the Beginning of Mahabharat

Mahabharat Story Credits: Internet sources, Amar Chitra Katha Part 1: The Beginning of Mahabharat The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, a nymph of Indra's court, from sage Vishwamitra, who secretly fell in love with her. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. He ruled for many years and was the founder of the Kuru dynasty. Unfortunately, things did not go well after the death of Bharata and his large empire was reduced to a kingdom of medium size with its capital Hastinapur. Mahabharata means the story of the descendents of Bharata. The regular saga of the epic of the Mahabharata, however, starts with king Shantanu. Shantanu lived in Hastinapur and was known for his valor and wisdom. One day he went out hunting to a nearby forest. Reaching the bank of the river Ganges (Ganga), he was startled to see an indescribably charming damsel appearing out of the water and then walking on its surface. Her grace and divine beauty struck Shantanu at the very first sight and he was completely spellbound. When the king inquired who she was, the maiden curtly asked, "Why are you asking me that?" King Shantanu admitted "Having been captivated by your loveliness, I, Shantanu, king of Hastinapur, have decided to marry you." "I can accept your proposal provided that you are ready to abide by my two conditions" argued the maiden. "What are they?" anxiously asked the king. -

The Festival of Jhofijhi-Tesu

The Festival of Jhofijhi-Tesu By L a x m i G. T e w a r i Sonoma State University’ Rohnert Park, CA On the Indian subcontinent, many different religious and cultural groups have been assimilated over the centuries into the mainstream of Indian society. Under the flexible protection of Hinduism, “ little communities ” observe many rituals, some of which have been linked to SansKritic literature. We find numerous shrines dedicated to various gods and godlings: some are worshiped in nationwide festivals, others only in isolated communities. Many shrines sit in ruins, their origins long forgotten, although passing pilgrims routinely pay their respects. Besides the gods worshiped in this intricate network of folk traditions, regional and national heroes are also eulogized in folk songs, folk theater, and festivals. The festival of Jhonjhl-Tesu is a regional festival of this type. It honors the folk hero Tesu and celebrates his marriage to a girl named Jhonjhi.1 My introduction to the festival was coincidental,2 but once introduced I was intrigued, because (1 )the elaborate observance of this festival seemed to be limited to a small geographical area (see map), (2) an extensive repertoire of folk songs was associated with it, and (3) all members of society participated in it. 1 his article discusses the mythological origins of the Jhonjhi- Tesu festival, describes the festival as it is celebrated today, gives re presentative song-texts for different segments of the festival, analyzes song types, and evaluates the social importance of the festival. I visited Nandana village (in the Kanpur district of Uttar Pradesh) three times (1973,19フ6, and 1977), in order to collect field data on this festival; I also made observations in Sandalpur village (1976)3 for comparative purposes. -

Man Sacrifice

MAN SACRIFICE Master E.K. MAN SACRIFICE Master E.K. Master E.K. Book Trust VISAKHAPATNAM – 530051 © Master E.K. Book Trust Available online: Master E.K. Spiritual and Service Mission www.masterek.org Institute for Planetary Synthesis www.ipsgeneva.com PREFACE Events exist to the created beings, and never to the creation. They are of two categories—the ordinary and the extraordinary. Events of the daily routine can be called the ordinary. Those that present themselves to change and rearrange the routine can be called the extraordinary. The daily routine of a living being, especially of a human being, includes only an expenditure of the span since there is no contribution in it to the expansion of consciousness. Food, sleep, fear, sex, profession, advantage and disadvantage are all of the divisions of the daily routine. The duration of their occurrence cuts out one’s span without contributing to the happiness of oneself or others. The only consequence (not benefit) of these routine incidents comes into existence as the growth of the body with age, the use of the senses and their organs along the patterns of habit and the sparkling of intelligence in a mechanised succession. The wise ones called the aggregate, the habit nature. One learns to seek happiness in the counterparts of the habit nature. Such a learning creeps in imperceptibly and is detected as “death” by the learned. Those who do not grow aware of PREFACE this interpret death in a different way. According to them, death is the inevitable disintegration of the physical body. It is evident that this definition is the result of gross illusion.