Anarchism in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download As a PDF File

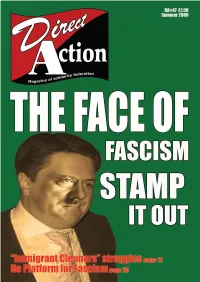

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

Vol. 35 Ha. 23 February, 1974

« 5p Vol. 35 Ha. 8 23 February, 1974 THE SOLS VIRTUE of this election question has some rather distur is its brevity. In the words bing factual answers, end the of Thomas Hcbbes (talking about bogey-stories that worked just something entirely different) it after the 1939-45 war will not is ’nasty, solitary, brutish and work again — short of a last- short’. Its nastiness is inhe minute scare-story like the rent in its cheap opportunism, Zinoviev letter or the Post- in its schoolboy slapstick; it Off ice -Savings annexation which is solitary in its complete iso worked well in the past. lation from anything connected There have been attempts tc with human life, it has its sol swing the focus of the election "I ’M SORRY, mv horny-handed o ld itary moment of truth in the onto the cost of living, this nroles--but in the National Int polling booth when one can real has driven the Conservatives to erest we must reduce vour stand- ise (usually too late) what a their refuge in the admittedly ard of living to improve out own.w farce it all is; it is brutish increased cost (and shortage) of in its frank appeals to our world food supplies. Now, as we baser instincts and its back- topics and problems it should go to press, the focus has shif cover are ignored, which is pro stage ’survival cf the fittest’ ted to the question of oil - not bably ju31 as veil for they, too. deals. of course the world shortage - are not soluble by political Its shortness was rendered but how to exploit Britain’s methods. -

El MIL I Puig Antich Cc Creative Commons LICENCIA CREATIVE COMMONS Autoría - No Derivados - No Comer Cial 1.0

Antonio Téllez Solà El MIL i Puig Antich cc creative commons LICENCIA CREATIVE COMMONS autoría - no derivados - no comer cial 1.0 - Aquesta llicència permet copiar, distribuir, exhibir i interpretar aquest text, sempre que es compleixin les següents condicions: BY Autoría-atribució: s’haurá de respectar l’ autoria del text i de la seva traducció. Sempre es farà constar el nom de l’autor/a i el del traductor/a. A No comercial: no es pot fer servir aquest treball amb finalitats comercials. = No derivats: no es pot alterar, transformar, modificar o reconstruir aquest text. - Els termes d’aquesta llicència hauran de constar d’una manera clara per qualsevol ús o distribució del text. - Aquestes condicions es podran alterar amb el permís explícit de l’autor/a. Aquest llibre té una llicència Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial. Per a consultar les con- dicions d’aquesta llicència es pot visitar http://cr eative commons.or g/licenses/by-nd-nc/1.0/ o enviar una car ta a Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, EUA. © 2006 Virus editorial/Lallevir S.L. Antonio Téllez Solà El MIL i Puig Antich Maquetació: Virus editorial Coberta: Xavi Sellés Primera edició en castellà: març de 1994 Primera edició en català: octubre de 2006 Lallevir S.L. VIRUS editorial C/Aurora, 23 baixos 08001 Barcelona T./fax: 934413814 C/e: [email protected] http://www.viruseditorial.net Imprés a: Imprenta LUNA Muelle de la Merced, 3, 2.º izq. 48003 Bilbao T.: 944167518 Fax: 944153298 ISBN-10: 84-96044-77-7 Salvador Puig Antich ISBN-13: 978-84-96044-77-7 Depósito Legal: Índex Nota editorial . -

Contemporary Catalan Theatre: an Introduction

CONTEMPORARY CATALAN THEATRE AN INTRODUCTION Edited by David George & John London 1996 THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS No. 1 Salvador Giner. The Social Structure of Catalonia (1980, reprinted 1984) No. 2 Joan Salvat-Papasseit. Selected Poems (1982) No. 3 David Mackay. Modern Architecture in Barcelona (1985) No. 4 Forty Modern Catalan Poems (Homage to Joan Gili) (1987) No. 5 E. Trenc Ballester & Alan Yates. Alexandre de Riquer (1988) No. 6 Salvador Espriu. Primera història d'Esther with English version by Philip Polack and Introduction by Antoni Turull (1989) No. 7 Jude Webber & Miquel Strubell i Trueta. The Catalan Language: Progress Towards Normalisation (1991) No. 8 Ausiàs March: A Key Anthology. Edited and translated by Robert Archer (1992) No. 9 Contemporary Catalan Theatre: An Introduction. Edited by David George í John London (1996) © for this edition by David George & John London © for the individual essays by the authors Produced and typeset by Interleaf Productions Limited, Sheffield Printed by The Cromwell Press, Melksham, Wiltshire Cover design by Joan Gili ISBN 0-9507137-8-3 Contents Acknowledgements 7 Preface 9 List of Illustrations 10 Introduction 11 Chapter 1 Catalan Theatrical Life: 1939-1993 Enric Gallén 19 The Agrupació Dramàtica de Barcelona 22 The Escola d'Art Dramàtic Adrià Gual and Committed Theatre 24 The Final Years of the Franco Regime 27 The Emergence of Resident Companies after the End of Francoism . .29 Success Stories of the 1980s 35 The Future 37 Chapter 2 Drama -

Change in National Identification a Study of the Catalan Case

Change in National Identification A study of the Catalan case María José Hierro Hernández TESIS DOCTORAL Universidad Autónoma de Madrid / 2012 DIRECTOR DE LA TESIS Dr. José Ramón Montero Gibert Departamento de Ciencias Políticas y Relaciones Internacionals a Dídac, perquè vaig començar aquest camí amb tu i vas ser el meu suport durant tot aquest temps ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the study of individual change in national identification and examines the factors which lie behind change under particular circumstances. The dissertation starts proposing a conceptual and analytical framework for the study of change along different dimensions of identification (self-categorization, content, salience and intensity). From here, the dissertation focuses on the study of change in the category of national identification in the Catalan context. The Catalan context is argued to be a suitable case study because it has two characteristics which render change in the category of national identification possible. These two characteristics are a center-periphery cleavage and the presence of a demographically important immigration population. The findings of my research are thus generalizable to other contexts which share these two characteristics with Catalonia. The dissertation offers an alternative explanation which complements the decentralization argument, and provides a better account for the periodic changes that are observed when identification with Spain and Catalonia is tracked over time. The dissertation contends that political parties’ mobilization of the center-periphery cleavage drives individual change in national identification. Although the cleavage structures competition between political parties in a permanent way, there are some periods during which a particular policy or issue sharpens conflict between national and regional parties and exacerbates the cleavage. -

Anarchism in Spain

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Spain Pedro García Guirao Pedro García Guirao Anarchism in Spain 2009 Guirao, Pedro García. “Anarchism, Spain.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 144–147. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 eración Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) ; Escuela Moderna Movement (The Modern School) ; Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) ; Mujeres Libres ; POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) ; Puig Antich, Salvador (1948–1974) ; Spanish Revolution References And Suggested Readings Álvarez, J. (1991) La ideología política del anarquismo español (1868– 1910). Madrid: Siglo XXI. Herrerín, A. (2004) La CNT durante el franquismo. Clandestinidad y exilio (1939–1975). Madrid: Siglo XXI. Kaplan, T. (1977) Anarchists of Andalusia (1868–1903). Princeton: Princeton University Press. Lorenzo, C. M. (1972) Los anarquistas españoles y el poder (1868– 1969). Paris: Ruedo Ibérico. Orwell, G. (2003) Homage to Catalonia. London: Penguin. Peirats, J. (1988) La CNT y la Revolución Española, Vol. 3. Madrid: La Cuchilla. Termes, J. (2000) Anarquismo y sindicalismo en España (1864–1881). Barcelona: Crítica. 11 considered political syndicalism, closer to socialism. The CNT uni- fied in 1961, but the unification was short-lived and the subsequent separation was so severe that the anarchist movement practically disappeared. On March 2, 1974, as Franco was nearing death, the young anar- Contents chist Salvador Puig Antich was executed by garrote. As a member of the anti-capitalist Iberian Liberation Movement (Movimiento Ibérico de Liberación, MIL), he had contacts with the French an- References And Suggested Readings . 11 archist movement and Spanish exiles living in Toulouse. -

This Is Not the Tale of Salvador Puig Antich

Number 46•47 one pound or two dollars July 2006 The Great Swindle: ‘This is not the tale of Salvador Puig Antich’ The movie Salvador about the up or misrepresent facts that they one•time member of the MIL or have no intention of disclosing, facts Thousand (1,000),* Salvador Puig bearing on the sham transition and Antich, executed by garrotte on 2 the familiar tragic consequences March 1974 in the Model Prison in then and now attendant upon this Barcelona will shortly be showing in approach [accepting the myth of the cinemas around the country [Spain]. ‘democratic’ transition] by the In these days when there is so working class and people of which much talk about the recovery of all are aware. Hardly surprising that historical memory, we are faced here they should cover their shame and with a brazen manipulation of the try to gloss over their guilty very memory which they purport to consciences. want to resuscitate through the Mediapro is Europe’s second making and screening of the movie, largest audio•visual multinational: a to which there has been a strange factory churning out most TV build•up over recent years. products, ads, movies and the like: it In fact a short while ago we got wields great control over the media, an appetiser on TV3 in the form of revising and adapting recent history its first program about the Transition. It was dedicated to as suits the authorities and keeping mum about past and Salvador Puig Antich and to the MIL. Now comes the present struggles. -

Essays in Anarchism and Religion: Volume II

Representations of Catholicism in Contemporary Spanish Anarchist-themed Film (1995–2011) Pedro García-Guirao King’s College London This essay explores the portrayal of Catholicism in eight Spanish anarchist-themed films. The first part discusses negative representations of the Catholic religion rehearsed in these films, set as they are mainly in the context of the Spanish Civil War. Among those representations are: the political and economic purpose of the Catholic Church’s control of education in Spain; the breaking of the religious vows of poverty and chastity, and the recourse to praising the vow of obedience when under scrutiny; and the breaking of the seal of the confessional. In the second part, the essay shows that those films also portray a Christianity which can be more solidary, revolutionary and attached to a different idealization of Christ, unlike the Church consisting of high-ranking members of the clergy. This second part also considers the notion of “secularization” and the extent to which anarchism has become an alternative religion in these films. The essay also reflects on the reliability of films as historical sources. Like any work of history, a film must be judged in terms of the knowledge of the past that we already possess. Like any work of history, it must situate itself within a body of other works, the on- going (multimedia) debate over the importance of events and the meaning of the past.1 Almost coinciding with the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, two respectively anarcho-communist (and 1 Robert Rosentone, ‘The historical film as real history’,Film- historia online, 1 (1995), 5–23 (p. -

Vol. 35 So. 3 17 January, 1973

5p Vol. 35 So. 3 17 January, 1973 AS WE GO to press it is possible policy? the offer of the T.U.C. not to that Mr. Heath vill play his mention the miners* "special trump card to solve all our en The miners are tough, they case" as a reason for vcge In ergy and economic problems at a have not forgotten the betrayal creases was never mentioned to by the Trade Unions in 1926 when stroke. He vill go to the courv- t^e liners. try, submit the resignation of they were left to fight on alone. his government to the queen or, Or the mirage of rationalization Meanwhile, all the cld stuff . in short, admit his policy has ,and the wholesale closing down about reds under the bed - or in failed and that, backed up by of pits and the switch to oil- the bed - is being dusted off confidence of some of the elect fuels which marked the Labour from other elections and Mr. orate he could try all over ag government's term of office. Heath’s sole comfort (if he needs ain — with almost the same The propaganda for the next one) is a Daily Mail opinion poDL policies! election has been well-placed On his own right flank Enoch beforehand - as usual. Whose Powell is going round saying ”1 It is quite unlikely that the finger is on the controls? Are told you so" as the deflationary miners - or the Arab sheikhs - the unions to have the power cuts in the Social Services bite will be impressed with this bid over the electorate or is the home. -

Organ the UNIFORM NAY the FACE IS ALWAYS

LAG organ the ANARCHIST BLACK CROSS Vol. IV No. 12 December 1976 15p A HAPPY NEW YEAR TO ALL OUR READERS - PLEASE REMEMBER YOUR COMRADES BEHIND BARS! (cover by Cohnnha l.onginorc. Citrragh Military Prison. Eire) ;i**i if. THE UNIFORM NAY BE DIFFERENT BUT THE FACE IS ALWAYS THE SANE NEWS OF THE MURRAYS APPEAL: The Dublin Supreme Court s. •:> t enced Noel Murray to life imprisonment and orderod a re-trial for Marie, to he held in the same no jury Special Criminal Court, on I he original charges of Capital Murder. Continued support and solidarity with the Murrays is vital. The London Murray Defence Group are h.oldin;- a publ ic meeting Friday 14 Jan- uary (.7pm), Conway Ha 1 I , Red Lion Sq^ Lo' flon WC1 We ur^c^ all to attend. Black Flag Vol. IV No. 12 Dec. '76 Provisional List of Libertarian Prisoners BACK IN THE USSR . still in Spanish Jails. Printed & Pub. by Black Flag Grp., The inhuman treatment of thousands of Subs. £3.00 per 12 issues (home) In the Carcel Modelo of Barcelona are people still continues. Vladimir Bukovsky Canada, Australia, N. Zealand Emilio Barbera Guiu, Jorge Cananellas (33) has now spent one third of his life (air mail) £6.00 (U.S. $3.00 Ronsell, Fernando Melallino Serrano. in prison, Since 1972 he has been in Black Flag, Over The Water, Under the October Amnesty, Vicente Vladimir prison, noted for its severity. Sanday, Orkney, KW17 2BL Iglesias Romero has been released. and has contracted a rheumatic heart, a In the prison of Granada are Jose Juan liver complaint and an eye infection as CNT APPEAL Martinez Ginez, Cristona Valenzuela a result of his treatment. -

Vol• 35 No. 5 2 February, 1974 REPORTS from Mining Areas Indi

anarchist w e e k ly Vol• 35 No. 5 2 February, 1974 REPORTS FROM mining areas indi Certainly the miners' fight have resulteB — and these cate that their ballot will give is the fight of every other wor cculd be better organised and run by associations of indi- the National Union of Mineworkers' ker, but as in 1926 the leader- w executive authority to call a ship of the other trade unions viduais to help others by mut national strike. An opinion will only bring their members ual aid — but overall the poll by the television programme into active struggle if they State now has far more control "Veek End World" among miners have nc other option. They will over our lives. We believe resulted in a clear majority of in fact be more concerned about that men and women are capable .’84$ in favour of a strike, the effects of the miners' of co-operating together in i Since the start of the overtime strike on the jobs of their mem running their own lives, taking ban miners1 attitudes have har bers. Both the constitutionally decisions for mutual benefit dened towards the National Coal minded leadership of the trade without the interference cr in Board’s offer. The government's unions and the politicians of deed without the existence of stand could bring abcut a major all parties are well aware of the State. confrontation unsurpassed since the danger« of a general strike, The government and the rep % the General Strike of 1926. even i it -ere called offici ressive forces of the State will P Then as now, the national news al lv. -

The New Catalan Cinema: Regional/National Film Production in a Globalised Context

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Allum, Stefanie (2016) The new Catalan cinema: regional/national film production in a globalised context. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/36248/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html THE NEW CATALAN CINEMA: REGIONAL/NATIONAL FILM PRODUCTION IN A GLOBALISED CONTEXT SG ALLUM PhD 2016 THE NEW CATALAN CINEMA: REGIONAL/NATIONAL FILM PRODUCTION IN A GLOBALISED CONTEXT STEFANIE GRANT ALLUM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research Undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences November 2016 1 Abstract The thesis explores the post-millennial boom in the production of Catalan films. Previous critical work on Catalan cinema has tended to focus primarily on documentary and realist forms.