A Free Speech Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOCRATES in the CLASSROOM Rationales and Effects of Philosophizing with Children Ann S

SOCRATES IN THE CLASSROOM Rationales and Effects of Philosophizing with Children Ann S. Pihlgren Socrates in the Classroom Rationales and Effects of Philosophizing with Children Ann S. Pihlgren Stockholm University ©Ann S. Pihlgren, Stockholm 2008 Cover: Björn S. Eriksson ISSN 1104-1625-146 ISBN (978-91-7155-598-4) Printed in Sweden by Elanders Sverige AB Distributor: Stockholm University, Department of Education To Kjell with love and gratitude. Contents Contents ........................................................................................................ vii Preface ............................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 1.1 Philosophizing and teaching ethics ..................................................................... 4 1.2 Some guidance for the reader ............................................................................ 5 1.3 Considerations ................................................................................................... 8 2 Research Goals and Design .................................................................. 9 2.1 Classroom interaction ......................................................................................... 9 2.2 Studying Socratic interaction ............................................................................ 10 2.3 Research questions ......................................................................................... -

Robert Maynard Hutchins, 1899-1977

The Yale Law Journal Volume 86, Number 8, July 1977 Robert Maynard Hutchins, 1899-1977 Herbert Brownellt Robert Maynard Hutchins, who died at Santa Barbara, California, on May 15, 1977, was Dean of the Yale Law School in 1928-29. He had served as Secretary of Yale University from 1923 to 1927. Upon his graduation from the Yale Law School in 1925, he joined the Law School's faculty as a Lecturer, a position he held from 1925 to 1927. He was Acting Dean of the Law School during the academic year 1927-28. Dean Hutchins was thirty years old when he left the Law School to become President and later Chancellor of the University of Chicago. Dean Hutchins' active leadership in the field of legal education during this brief span of years was notable for the innovations he sponsored in the Law School's curriculum and in particular for the establishment of the Institute of Human Relations. His erudition, his inquisitive mind, and his theories of proper relationships among law, economics, political science, and psychology left an indelible im- print upon the Yale Law School of his time. His initiatives, more- over, led to fruitful interdisciplinary research programs that have had lasting effects upon legal education in this country. The main endeavors of Dean Hutchins' career, and his publicly known achievements, came in later years while he was a founder, Chief Executive Officer, and President of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, based in California. But many of the in- gredients of his brilliant intellectual success first came to light during his deanship at the Yale Law School. -

Unrestrained Growth in Facilities for Athletes: Where Is the Outrage?

Unrestrained Growth in Facilities for Athletes: Where is the Outrage? September 17, 2008 By Frank G. Splitt "It requires no tabulation of statistics to prove that the young athlete who gives himself up for months, to training under a professional coach for a grueling contest, staged to focus the attention of thousands of people, and upon which many thousands of dollars will be staked, will find no time or energy for serious intellectual effort. The compromises that have to be made to keep such a student in the college and to pass them through to a degree give an air of insincerity to the whole university-college regime." 1 —Henry Smith Pritchett, Former MIT President (1900-1906) and President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (1906-1930). Sol Gittleman, a former provost at Tufts University, wrote to me with reference to Brad Wolverton’s recent article, “Rise in Fancy Academic Centers for Athletes Raises Questions of Fairness,”2 saying: "This would be a joke, if it weren't for articles that state how public universities are losing out in hiring to the well-heeled privates. So, while faculty flee to the private sector, the public universities build these Xanadus for athletes. Have we lost our minds? Where are the presidents?” Re: Dr. Gittleman’s first question: Have we lost our minds?—Based on the sad state of affairs in America’s system of higher education, it would certainly seem so, but there is no way to prove it as yet. However, taking a queue from Henry Pritchett, it requires no tabulation of statistics to prove that America’s system of higher education has been reeling under the negative impact of over commercialized college sports. -

ED370493.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 493 HE 027 453 AUTHOR Young, Raymond J.; McDougall, William P. TITLE Summer Sessions in Colleges and Universities: Perspectives, Practices, Problems, and Prospects. INSTITUTION North American Association of Summer Sessions, St. Louis, MO. SPONS AGENCY Phi Delta Kappa, Bloomington, Ind.; Washington State Univ., Pullman. Coll. of Agriculture.; Western Association of Summer Session Administrators. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 318p. AVAILABLE FROMNorth American Association of Summer Sessions, 11728 Summerhaven Dr., St. Louis, MO 63146 ($8.50). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Programs; *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Higher Education; *Program Administration; Program Development; School Schedules; Summer Programs; *Summer Schools; Universities ABSTRACT This book offers normative information about various operational facets of collegiate summer activities, places the role of the modern day collegiate summer session in evolutioLary perspective, and provides baseline information produced by four national studies and one regir)nal study. The book's chapters focus on: (1)a global perspective and orientation to the topic of collegiate summer sessions and a research review;(2) the historical of the evolution of summer sessions;(3) various features of summer terms, including organization and administration, curriculum and instructional activities, students, and staff;(4) historical development and influence of the collegiate calendar and its relationship to summer sessions;(5) historical development, role, nature, and contribution of professional associations relating to summer sessions;(6) major problems, issues, and trends regarding collegiate summer sessions; and (7) evaluation of summer sessions. An appendix provides a brief program evaluation proposal. (Contains approximately 300 references.)(JDD) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

THE PHILOSOPHY of GENERAL EDUCATION and ITS CONTRADICTIONS: the INFLUENCE of HUTCHINS Anne H. Stevens in February 1999, Universi

THE PHILOSOPHY OF GENERAL EDUCATION AND ITS CONTRADICTIONS: THE INFLUENCE OF HUTCHINS Anne H. Stevens In February 1999, University of Chicago president Hugo Sonnen- schein held a meeting to discuss his proposals for changes in un- dergraduate enrollment and course requirements. Hundreds of faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates assembled in pro- test. An alumni organization declared a boycott on contributions until the changes were rescinded. The most frequently cited com- plaint of the protesters was the proposed reduction of the “com- mon core” curriculum. The other major complaint was the proposed increase in the size of the undergraduate population from 3,800 to 4,500 students. Protesters argued that a reduction in re- quired courses would alter the unique character of a Chicago edu- cation: “such changes may spell a dumbing down of undergraduate education, critics say” (Grossman & Jones, 1999). At the meet- ing, a protestor reportedly yelled out, “Long live Hutchins! (Grossman, 1999). Robert Maynard Hutchins, president of the University from 1929–1950, is credited with establishing Chicago’s celebrated core curriculum. In Chicago lore, the name Hutchins symbolizes a “golden age” when requirements were strin- gent, administrators benevolent, and students diligent. Before the proposed changes, the required courses at Chicago amounted to one half of the undergraduate degree. Sonnenschein’s plan, even- tually accepted, would have reduced requirements from twenty- one to eighteen quarter credits by eliminating a one-quarter art or music requirement and by combining the two-quarter calculus re- quirement with the six quarter physical and biological sciences requirement. Even with these reductions, a degree from Chicago would still have involved as much or more general education courses than most schools in the country. -

Guide to the Robert Maynard Hutchins Papers 1884-2000

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Robert Maynard Hutchins Papers 1884-2000 © 2014 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 4 Information on Use 4 Access 4 Restrictions on Use 4 Citation 4 Biographical Note 5 Scope Note 7 Related Resources 9 Subject Headings 10 INVENTORY 11 Series I: Personal 11 Subseries 1: General 11 Subseries 2: Biographical 13 Series II: Correspondence 15 Series III: Subject Files 208 Series IV: Yale University 212 Series V: University of Chicago 213 Subseries 1: General 213 Subseries 2: Publicity 218 Series VI: Encyclopædia Britannica 228 Subseries 1: General 228 Subseries 2: Correspondence 235 Subseries 3: Board of Editors 241 Subseries 4: Content Development 244 Series VII: Commission on Freedom of the Press 252 Series VIII: Committee to Frame a World Constitution 254 Series IX: Ford Foundation, Fund for the Republic, and Center for Study of Democratic256 Institutions Subseries 1: Administrative 256 Subseries 2: Programs and Events 261 Series X: Writings 267 Subseries 1: General 269 Subseries 2: Books 270 Subseries 3: Articles 275 Sub-subseries 1: Articles 275 Sub-subseries 2: Correspondence 294 Subseries 4: Speeches 297 Subseries 5: Engagements 339 Series XI: Honors and Awards 421 Series XII: Audiovisual 424 Series XIII: Books 436 Series XIV: Oversize 439 Series XV: Restricted 440 Subseries 1: Financial and Personnel Information 441 Subseries 2: Student Information 441 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.HUTCHINSRM Title Hutchins, Robert Maynard. Papers Date 1884-2000 Size 238.5 linear feet (465 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. -

RF Annual Report

The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1913-14 TEE RO-.-K'.r.'.'.I £E 7- 1935 LIBRARY The Rockefeller Foundation 61 Broadway, New York © 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation ^«1 \we 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation July 6, 1915. > To the Trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation: Gentlemen:— I have the honor to transmit to you herewith a report on the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation and on its financial operations from May 14,1913, the date on which its charter was received from the Legislature of the State of New York, to December 31, 1914, a period of eighteen months and a half. The following persons named in the act of incorporation became, by the formal acceptance of the Charter, May 22, 1913, the first Board of Trustees: John D. Rockefeller, of New York. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., of New York. Frederick T. Gates, of Montclair, N, J. Harry Pratt Judson, of Chicago, 111. Simon Flexner, of New York. Starr J. Murphy, of Montclair, N. J. Jerome D. Greene, of New York. Wickliffe Rose, of Washington, D. C. Charles 0. Heydt, of Montclair, N. J. To the foregoing number have been added by election the following Trustees: Charles W. Eliot, of Cambridge, Mass.1 8 A. Barton Hepburn, of New York. G Appended hereto are the detailed reports of the Secretary and the Treasurer of the Rockefeller Foundation and of the Director General of the International Health Commission, JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., President. 1 Elected January 21, 1914. 9 Elected March 18, 1914. 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation To the President of the Rockefeller Foundation: Sir:— I have the honor to submit herewith my report as Secretary of the Rockefeller Foundation for the period May 14, 1913, to December 31, 1914. -

Academic Faculty Address-2017

A Ressourcement Vision for Graduate Theological Education Academic Faculty Address-2017 Thomas A. Baima Mundelein Seminary August 11, 2017 I want to welcome everyone to the first of our Academic Faculty meetings for the 2017- 2018 school year. I hope all of you had a refreshing summer. This meeting is the result of comments by some of you that the academic department did not have the same opportunity as the formation department for planning and interaction. It is for this reason that I added this morning to the meetings at the opening of the school year. We do need time to work together as a group on the common project of seminary education. Those of you who are more senior will remember that we used to meet for two full days at the opening of the school year and again at the opening of the beginning of the new year. Without those meetings, we have lost much of the time we used to work together. So, I hope this morning will restore some of that, and at the same time not wear everyone out. Here is my plan for the morning. First, I’m going to do some introductions of our new members. Next, I want to offer some remarks about the vision of higher education. I do this because the academic department is entrusted with the responsibility for the intellectual pillars and shares responsibility for the pastoral pillar 1 with Formation. As such, we are part of the larger higher education enterprise both of this country and of the Catholic Church internationally. -

DOCUVENT RESUME ED 286 394 HE 020 596 AUTHOR Mcarthur, Benjamin Revisiting Hutchins and "The Higher Learning in America.&Qu

DOCUVENT RESUME ED 286 394 HE 020 596 AUTHOR McArthur, Benjamin TITLE Revisiting Hutchins and "The Higher Learning in America." PUB DATE Apr 87 NOTE 31p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Washington, DC, April 20-24, 1987). Several pages may not reproduce well because they contain light print. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Citizenship; *Civil Liberties; *College Presidents; College Role; *Educational Change; *Educational History; Higher Education; *Liberal Arts IDENTIFIERS *Hutchins (Robert) ABSTRACT The career of Robert Maynard Hutchins and hiz 1936 book, "The Higher Learning in America," which addressed the college liberal arts curriculum, are discussed. Hutchins was a controversial university president in the 1930s and 1940s. He is normally remembered as an Aristotelian and a champion of civil liberties, the Great Books, and adult education. Hutchins's undergraduate work was done at Oberlin College and Yale University, and he received his law degree from Yale. He served as a lecturer and dean of the Yale Law School and was a successful fund raiser in a number of posts. He was an administrator at age 21 and at age 30 he became president of the University of Chicago, where he had a 22-year tenure. During Hutchin's second career, he served at the Ford Foundation's Fund for the Republic, which was devoted to the study of American freedom and civil liberties. He was the founder of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions at Santa Barbara. His book, "The Higher Learning in America," advocated that college learning should be pervasively intellectual rather than a means to develop character or prepare for a vocation. -

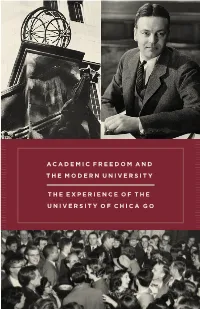

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W. -

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital By

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital by K. Page Boyer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Educational Leadership) at the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair LEO Lecturer II John Burl Artis Professor M. Robert Fraser Copyright 2016 by K. Page Boyer All Rights Reserved i Dedication To my family “To know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.” ~ Nicolaus Copernicus ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair of my dissertation committee, for her probity and guidance concerning theories of school administration and leadership, organizational theory and development, educational law, legal and regulatory issues in educational administration, and curriculum deliberation and development. Thank you to Dr. John Burl Artis for his deep knowledge, political sentience, and keen sense of humor concerning all facets of educational leadership. Thank you to Dr. M. Robert Fraser for his rigorous theoretical challenges and intellectual acuity concerning the history of Christianity and Christian Thought and how both pertain to teaching and learning in America’s colleges and universities today. I am indebted to Baker Library at Dartmouth College, Regenstein Library at The University of Chicago, the Widener and Houghton Libraries at Harvard University, and the Hatcher Graduate Library at the University of Michigan for their stewardship of inestimably valuable resources. Finally, I want to thank my family for their enduring faith, hope, and love, united with a formidable sense of humor, passion, optimism, and a prodigious ability to dream. -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER AND THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER XVEDUCATION XV THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO William Rainey Harper, 1882, Baldwin and Harvey Photographic Artists, Chicago. I I “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” William Rainey Harper and the University of Chicago INTRODUCTION e meet today at a noteworthy moment in our history. The College has now met and surpassed the enrollment W goals established by President Hugo F. Sonnenschein in 1996, and we have done so while increasing our applicant pool, our selectivity, and the overall level of participation by the faculty in the College’s instructional programs. Many people—College faculty, staff, alumni, and students—have contributed to this achievement, and we and our successors owe them an enormous debt of gratitude. I am particularly grateful to the members of the College faculty—as I know our students and their families are—for the crucial role that you played as teachers, as mentors, as advisers, and as collaborators in the academic achievements of our students. The College lies at the intellectual center of the University, an appropriate role for the University’s largest demographic unit. We affirm academic excellence as the primary norm governing all of our activities. Our students study all of the major domains of human knowledge, and they do so out of a love of learning and discovery. They undertake general and specialized studies across the several disciplines, from the humanities to the natural sciences and mathematics to the social sciences and beyond, This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 25, 2005.