ED370493.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF Annual Report

The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1913-14 TEE RO-.-K'.r.'.'.I £E 7- 1935 LIBRARY The Rockefeller Foundation 61 Broadway, New York © 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation ^«1 \we 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation July 6, 1915. > To the Trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation: Gentlemen:— I have the honor to transmit to you herewith a report on the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation and on its financial operations from May 14,1913, the date on which its charter was received from the Legislature of the State of New York, to December 31, 1914, a period of eighteen months and a half. The following persons named in the act of incorporation became, by the formal acceptance of the Charter, May 22, 1913, the first Board of Trustees: John D. Rockefeller, of New York. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., of New York. Frederick T. Gates, of Montclair, N, J. Harry Pratt Judson, of Chicago, 111. Simon Flexner, of New York. Starr J. Murphy, of Montclair, N. J. Jerome D. Greene, of New York. Wickliffe Rose, of Washington, D. C. Charles 0. Heydt, of Montclair, N. J. To the foregoing number have been added by election the following Trustees: Charles W. Eliot, of Cambridge, Mass.1 8 A. Barton Hepburn, of New York. G Appended hereto are the detailed reports of the Secretary and the Treasurer of the Rockefeller Foundation and of the Director General of the International Health Commission, JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., President. 1 Elected January 21, 1914. 9 Elected March 18, 1914. 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation To the President of the Rockefeller Foundation: Sir:— I have the honor to submit herewith my report as Secretary of the Rockefeller Foundation for the period May 14, 1913, to December 31, 1914. -

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W. -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER AND THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER XVEDUCATION XV THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO William Rainey Harper, 1882, Baldwin and Harvey Photographic Artists, Chicago. I I “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” William Rainey Harper and the University of Chicago INTRODUCTION e meet today at a noteworthy moment in our history. The College has now met and surpassed the enrollment W goals established by President Hugo F. Sonnenschein in 1996, and we have done so while increasing our applicant pool, our selectivity, and the overall level of participation by the faculty in the College’s instructional programs. Many people—College faculty, staff, alumni, and students—have contributed to this achievement, and we and our successors owe them an enormous debt of gratitude. I am particularly grateful to the members of the College faculty—as I know our students and their families are—for the crucial role that you played as teachers, as mentors, as advisers, and as collaborators in the academic achievements of our students. The College lies at the intellectual center of the University, an appropriate role for the University’s largest demographic unit. We affirm academic excellence as the primary norm governing all of our activities. Our students study all of the major domains of human knowledge, and they do so out of a love of learning and discovery. They undertake general and specialized studies across the several disciplines, from the humanities to the natural sciences and mathematics to the social sciences and beyond, This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 25, 2005. -

“Teaching at a University of a Certain Sort” 2

“ T E A C H I N G A T A U N I V E R S I T Y O F A CERTAIN SORT” E D U C A T I O N A T T H E UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OVER THE PAST CENTURY J o h n W . B o y e r OCCASIONAL PAPERS O N H I G H E R EDUCATION XXI XXITHE COLLEGE O F T H E UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Ralph W. Tyler, Chief Examiner, Board of Examinations, 1938 –1953 “TEACHING AT A UNIVERSITY O F A C E R T A I N S O R T ” Education at the University of Chicago over the Past Century INTRODUCTION he College begins this academic year with slightly more than 5,300 students. Our first-year class of 1,416 stu- T dents plus 42 transfer students will sustain the College at its current size. The talent, creativity, and ambition of our students; the extraordinary pool of applicants from which they were chosen; and their eagerness to participate with all of us in the en- terprise of learning at the College should make us confident that the academic year that is just underway will be stimulating and rewarding. The Admissions data we have heard today are one of several ways to measure the achievements of our students. We might also cite the schol- arships and fellowships they have won in the past decade—including 14 Rhodes Scholarships, 117 Fulbrights, and 36 Goldwaters. Less familiar names are also on the list: In 2011 two students won Woodrow Wilson– Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellowships for Aspiring Teachers of Color, supporting enrollment in graduate education programs that lead to a master’s degree and teaching certification; and a third student won a Jack Kent Cooke Foundation Graduate Arts Award, supporting three years of This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 18, 2011. -

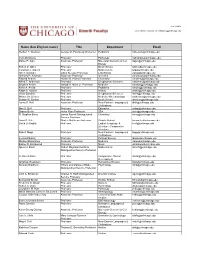

(A to Z by Last Name) Title Department Email Herbert T

As of 12.20.18 Corrections? Contact [email protected] Name (A to Z by last name) Title Department Email Herbert T. Abelson George M. Eisenberg Professor Pediatrics [email protected] Cyril Abrahams Professor Pathology [email protected] Daniel P. Agin Associate Professor Molecular Genetics & Cell [email protected] Biology Robert Z. Aliber Professor Booth School [email protected] Jonathan L. Alperin Professor Mathematics [email protected] Albert Alschuler Julius Kreeger Professor Law School [email protected] Anthony P. Amarose Associate Professor Genetics [email protected] Edward Anders Horace B. Horton Professor Chemistry [email protected] Alfred T. Anderson Professor Geophysical Sciences [email protected] Stephen Archer Harold H. Hines Jr. Professor Medicine [email protected] Rene A. Arcilla Professor Pediatrics [email protected] Ralph A. Austen Professor History [email protected] Victor Barcilon Professor Geophysical Sciences [email protected] Michael A. Becker Professor Medicine-Rheumatology [email protected] Selwyn W. Becker Professor Booth School [email protected] Lanny D. Bell Associate Professor Near Eastern Languages & [email protected] Civilizations Max S. Bell Professor Education [email protected] Sharon Berlin Helen Ross Professor SSA [email protected] R. Stephen Berry James Franck Distinguished Chemistry [email protected] Service Professor Hans D. Betz Shailer Matthews Professor Divinity School [email protected] David Bevington Professor English Language & [email protected] Literature; Comparative Literature Robert Biggs Professor Near Eastern Languages & [email protected] Civilizations Leonard Binder Professor Political Science [email protected] Michael Blackstone Associate Professor Medicine [email protected] Easley R. Blackwood Professor Music [email protected] Spencer Bloch Robert Maynard Hutchins Mathematics [email protected] Distinguished Service Professor R. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President Scrapbooks 1889-1943

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President Scrapbooks 1889-1943 © 2012 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 4 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Series I: News Clippings 5 Series II: Communications 6 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.OFCPRESSCRAPBOOK Title University of Chicago. Office of the President. Scrapbooks Date 1889-1943 Size 51.5 linear feet (34 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains scrapbooks compiled by the University of Chicago Office of the President. They contain news clippings related to the University, its founding, and its staff and leadership, and collections of official communications issued by the President's office. The collection spans the years 1889-1943, with the bulk of the material dating from 1908 to 1910. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Office of the President. Scrapbooks, Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Historical Note On September 18, 1890, William Rainey Harper was elected by the Board of Trustees as the first President of the University of Chicago. President Harper assumed office on July 1, 1891. The University has had 13 presidents in total: • William Rainey Harper – 1891-1906 • Harry Pratt Judson – 1907-1923 • Ernest DeWitt Burton – 1923-1925 • Max Mason – 1925-1928 3 • Robert Maynard Hutchins – 1929-1951 • Lawrence Kimpton – 1951-1960 • George W. -

Building the Chicago School MICHAEL T

American Political Science Review Vol. 100, No. 4 November 2006 Building the Chicago School MICHAEL T. HEANEY University of Florida JOHN MARK HANSEN University of Chicago he Chicago School of Political Science, which emerged at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, is widely known for its reconception of the study of politics as a scientific endeavor T on the model of the natural sciences. Less attention has been devoted to the genesis of the school itself. In this article, we examine the scientific vision, faculty, curriculum, and supporting institutions of the Chicago School. The creation of the Chicago School, we find, required the construction of a faculty committed to its vision of the science of politics, the muster of resources to support efforts in research and education, and the formation of curriculum to educate students in its precepts and methods. Its success as an intellectual endeavor, we argue, depended not only on the articulation of the intellectual goals but also, crucially, on the confluence of disciplinary receptiveness, institutional opportunity, and entrepreneurial talent in support of a science of politics. central force in the evolution of political sci- After World War II, the apostles of the Chicago ence, like other of the social sciences, has been School—–those who pursued doctoral studies at Athe incorporation of the methods of the nat- Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s—–moved to faculty ural sciences. During the 1920s and 1930s, a group of positions at leading universities around the United scholars advocating the development of a “science” of States: V.O. -

The Dialectic of the University: His Master's Voice

R. Gaustavino Company. Akoustolith plaster. Detail. From Sweet’s Architectural Trade Catalog 1927–1928 (1927). 82 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00176 The Dialectic of the University: His Master’s Voice REINHOLD MARTIN During the first three months of 1872, a twenty-seven-year-old professor of classical philology delivered five lectures before the Öffentliche Akademische Gesellschaft (or Public Academy) at the University of Basel. In the last of his lectures, Friedrich Nietzsche offered this definition of the modern university: “One speaking mouth, with many ears, and half as many writing hands— there you have to all appearances, the external academic apparatus; the uni- versity education machine in action.”1 In Nietzsche’s university, a newfound zone of academic freedom separated professor and audience, but, as he point- edly remarked to his European listeners, standing behind it all, at some “mod- est distance,” was the state, to remind all concerned “that it is the aim, the goal, the be-all and end-all, of this curious speaking and hearing procedure.”2 Nietzsche and his extramural audience were bound together by a conti- nental university system that reflected the Prussian reforms begun around 1810, by which universities became knowledge-seeking instruments of the new nation-states, reorganized around the kind of primary research the young philologist was doing in Basel as he prepared to publish his first book, The Birth of Tragedy (1872).3 But even in translation, we can hear the indignation in Nietzsche’s voice at what he took to be servitude masked as freedom, administered at a distance by feeble, sycophantic bureaucrats, guardians of a national culture dedicated to nothing more than their (and its) self-preservation. -

Nobel Prize Ceremony at International House

World Beyond the Headlines Lecture Annual 59th Street Spring Festival Series Mark Gevisser Festival Jazz Series Series—Indian Thabo Mbeki— of Nations March 22, Performing Arts The Dream Deferred Celebration April 4, May 2, April 23–25 May 5 May 17 and June 7 SPRING 2009 I-HOUSE LIFE Nobel Prize Ceremony at International House The 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics was and the Enrico Fermi Institute, was understandable whole.” After nearly presented to Professor Yoichiro Nambu born in Tokyo in 1921. Dr. Nambu fifty years, the Royal Swedish Academy on December 10—not in Stockholm, arrived in the U.S. in 1952 to study with of Science has honored Dr. Nambu’s but in Hyde Park. The Assembly Hall at J. Robert Oppenheimer at Princeton achievements as he takes his place as International House was the site University’s Institute for Advanced the 28th Nobel laureate in Physics at for this historic event, with the hall’s Study. He came to the University the University of Chicago. colorful flag display adding to the of Chicago as a Research Associate in pageantry of the trumpeters’ herald 1954, in part due to the reputation that opened the ceremony. of Enrico Fermi (himself a fellow Nobel International House not only laureate in Physics and a 1940–1942 International House Nobel Laureates provided an elegant setting for this resident of International House). high-profile occasion, but efficiently The scientific work that resulted International House proudly recog- who achieved the first controlled handled the innumerable details in Dr. Nambu’s Nobel Prize—“the nizes its alumni, who have been self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction associated with an event of this nature discovery of the mechanism of sponta- honored with Nobel Prizes in their under the west stands of Stagg involving matters of protocol. -

RF Annual Report

The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report J!ii 2 1273 Jj.\ J- .t •;,-,. ;.;• . 1916 The Rockefeller Foundation 61 Broadway, New York 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation CONTENTS PAGE REPORT OF THE SECRETARY 7 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR GENERAL OF THE INTER- NATIONAL HEALTH BOARD 49 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF THE CHINA MEDICAL BOARD 281 / REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF THE WAR RELIEF COMMISSION 809 REPORT OF THE TREASURER 339 APPENDIX: I. Constitution and By-Laws 397 II. Rules of the International Health Board . 408 III. Instructions to the War Relief Commission . 411 IV. Letters of Gift 413 V, Institute of Hygiene. Memorandum by Dr. William H. Welch and Mr. Wickliffe Rose . 415 VI. War Relief Expenditures 4£8 INDEX ". 433 2 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION Report for the Year 1916 To the Members of the Rockefeller Foundation: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith a report on the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation and on its financial operations for the year 1916. The following members were re-elected at the annual meeting of January, 1916, for a term of three years: John Davison Rockefeller, of New York, N. Y., John Davison Rockefeller, Jr., of New York, N.Y., Frederick Taylor Gates, of Montclair, New Jersey. At the same meeting the following additional members were elected: Martin Antoine Ryerson, to serve until the annual meeting of 1919, and Harry Emerson Fosdick and Frederick Strauss, to serve until the annual meeting of 1918. Appended hereto are the detailed reports of the Secre- tary and the Treasurer of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Director General of the International Health Board, the Director of the China Medical Board, and the Chairman of the War Relief Commission. -

“True to the Highest Ideals of the University” Viewing Conflict As a Catalyst for Reevaluating Institutional Standards and Practices

“TRUE TO THE HIGHEST IDEALS OF THE UNIVERSITY” VIEWING CONFLICT AS A CATALYST FOR REEVALUATING INSTITUTIONAL STANDARDS AND PRACTICES By Gina Vizvary A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Higher, Adult, and Lifelong Education – Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT “TRUE TO THE HIGHEST IDEALS OF THE UNIVERSITY” VIEWING CONFLICT AS A CATALYST FOR REEVALUATING INSTITUTIONAL STANDARDS AND PRACTICES By Gina Vizvary Conflict at institutions of higher education is not new. However, with the prevalence of the internet, disputes now capture the attention of national media outlets and can spread quickly to a large audience via social media sites and online publications. Over the last decade, conflicts over athletics, curricular changes, online classes, and special-interest research initiatives have pitted faculty against faculty and faculty against administration. At times whole campus communities may become involved in the fray, from students to staff to alumni. Organizational literature on colleges and universities tells us that higher education institutions have unique characteristics that distinguish them from the business or for-profit world. Universities must continuously innovate and adapt in order to stay relevant to society. Yet they are also decades or centuries old, with traditions, legacies, and unique cultures that pervade campus life. This tension between the old and the new, tradition and innovation, presents challenges to university leaders. When new decisions seem to contradict longstanding traditions, there is bound to be backlash. The focus of the current study was to understand the tensions that fuel university conflict. The study utilized a historical perspective to research the conflict over the planning and implementation of the Milton Friedman Institute (MFI) at the University of Chicago in 2008. -

Extensions of Remarks E177 HON. STEPHANIE TUBBS JONES HON

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E177 down and find someone who is making a dif- HANNA HOLBORN GRAY Married: Charles M. Gray, 1954, A.B. Har- ference. Maybe it's a Bosnian Serb who saves THE HARRY PRATT JUDSON DISTINGUISHED vard University 1949, Ph.D. Harvard Univer- a Muslim, or vice versa. Or a Palestinian SERVICE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, THE UNI- sity 1956. who reaches out to an Israeli. We need to VERSITY OF CHICAGO Education honor these people who have risked every- Hanna H. Gray was President of the Uni- B.A. Bryn Mawr College 1950 thing to help someone different from them- versity of Chicago from July 1, 1978 through Fulbright Scholar, Oxford University 1950±51 selves.'' June 30, 1993, and is now President Emeritus. Ph.D. (History) Harvard University 1957 Mrs. Gray is a historian with special inter- f 1953±54ÐInstructor, Bryn Mawr College ests in the history of humanism, political 1955±57ÐTeaching Fellow, Harvard Univer- A TRIBUTE TO JULIANNE M. and historical thought, and politics in the sity DIULUS, BEREA MUNICIPAL COURT Renaissance and the Reformation. She 1957±59ÐInstructor, Harvard University taught history at the University of Chicago 1959±60ÐAssistant Professor, Harvard Uni- from 1961 to 1972 and is now the Harry Pratt versity; Head Tutor, Committee on De- HON. STEPHANIE TUBBS JONES Judson Distinguished Service Professor of grees in History and Literature OF OHIO History in the University of Chicago's De- 1961±64ÐAssistant Professor, University of partment of History. Chicago IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES She was born on October 25, 1930, in Heidel- 1963±64ÐVisiting Lecturer, Harvard Univer- Tuesday, February 9, 1999 berg, Germany.