The Dialectic of the University: His Master's Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Celebration of the Contributions of Dr. Mortimer J. Adler

A Celebration of the Contributions of Dr. Mortimer J. Adler August 19-21,1994 Aspen, Colorado Contents (interactive) Mortimer J. Adler: Philosopher at Midday- Jeffrey D. Wallin...................51 MJA, POLITICS: Summary - John Van Doren............................................76 Mortimer Adler: The Political Writings - John Van Doren........................79 Remarks – Mortimer J. Adler.......................................................................93 From the Editor’s Desk - Sydney Hyman...................................................95 Mortimer Adler and The Aspen Institute - Sidney Hyman........................99 Authors........................................................................................................118 51 Mortimer J. Adler: Philosopher at Midday Jeffrey D. Wallin ortimer J. Adler has made an unusual number of difficult M ideas accessible to “everybody.” Perhaps that is why he has been so uncharitably dismissed as a “popular” philosopher by his critics, a good number of whom come from that narrow breed of specialists once dismissed by Nietzsche as equipped at best to study the lives of a single species of insect, say, the leech, or that being too broad, perhaps only the leech’s brain. Adler is not a spe- cialist. He speaks to broad issues, issues of importance to all of us as men and women. Even more surprising, he speaks without jar- gon, evasion or irony. Unlike the owl of Minerva, which is said to begin its flight at dusk, this is one philosopher who learns and teaches in direct sunlight. Among the most important topics Adler has shed light upon are liberal education, democracy and human nature. Adler favors all of them, by the way. And nothing could further distance him from the strongest trends in American education. * * * In early May 1994 The New York Times carried a story about a controversy raging in Lake County, Florida. -

ED370493.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 493 HE 027 453 AUTHOR Young, Raymond J.; McDougall, William P. TITLE Summer Sessions in Colleges and Universities: Perspectives, Practices, Problems, and Prospects. INSTITUTION North American Association of Summer Sessions, St. Louis, MO. SPONS AGENCY Phi Delta Kappa, Bloomington, Ind.; Washington State Univ., Pullman. Coll. of Agriculture.; Western Association of Summer Session Administrators. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 318p. AVAILABLE FROMNorth American Association of Summer Sessions, 11728 Summerhaven Dr., St. Louis, MO 63146 ($8.50). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Programs; *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Higher Education; *Program Administration; Program Development; School Schedules; Summer Programs; *Summer Schools; Universities ABSTRACT This book offers normative information about various operational facets of collegiate summer activities, places the role of the modern day collegiate summer session in evolutioLary perspective, and provides baseline information produced by four national studies and one regir)nal study. The book's chapters focus on: (1)a global perspective and orientation to the topic of collegiate summer sessions and a research review;(2) the historical of the evolution of summer sessions;(3) various features of summer terms, including organization and administration, curriculum and instructional activities, students, and staff;(4) historical development and influence of the collegiate calendar and its relationship to summer sessions;(5) historical development, role, nature, and contribution of professional associations relating to summer sessions;(6) major problems, issues, and trends regarding collegiate summer sessions; and (7) evaluation of summer sessions. An appendix provides a brief program evaluation proposal. (Contains approximately 300 references.)(JDD) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Political Science 5 Comparative Government Course Syllabus – Spring, 2015

POLITICAL SCIENCE 5 COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENT COURSE SYLLABUS – SPRING, 2015 Course Sections, Reedley College: Instructor: Dr. Tellalian 55511: MW, 2:00 – 3:15 P.M., CCI-200 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 9:00 – 10:00 A.M. Fridays, 10:00 – 10:30 A.M., 1:00 – 2:30 P.M., and by appointment. Course Description: This course provides an introduction to the basic workings of various political systems throughout the world, with an emphasis on both the formal (i.e., governmental institutions, political processes) and informal (i.e., cultural exchanges) dimensions of politics. Students will engage in comparisons of these political systems using some of the basic concepts of political analysis. Course Objectives: In the process of completing this course, students will: 1. analyze political and governmental systems by using the comparative method, including, but not limited to representative democracies, parliamentary democracies, totalitarian systems, and authoritarian systems. 2. examine the political philosophies and historical cultural values of selected governments. 3. survey the variables that influence the governmental direction of transitional states. 4. examine the impact of regional, economic, historical, and cultural factors on political institutions and behavior within a country. 5. explore the forms of political participation, including individual actions and pluralist influences. 6. analyze the economic systems of the selected countries and how these relate to their systems of government and geopolitical standing. 7. evaluate the functioning of various political and governmental systems in light of current events. 8. appraise the liberties and rights of people living under various political/governmental regimes. 1 Required Texts: Lord, Carnes, trans. -

RF Annual Report

The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1913-14 TEE RO-.-K'.r.'.'.I £E 7- 1935 LIBRARY The Rockefeller Foundation 61 Broadway, New York © 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation ^«1 \we 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation July 6, 1915. > To the Trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation: Gentlemen:— I have the honor to transmit to you herewith a report on the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation and on its financial operations from May 14,1913, the date on which its charter was received from the Legislature of the State of New York, to December 31, 1914, a period of eighteen months and a half. The following persons named in the act of incorporation became, by the formal acceptance of the Charter, May 22, 1913, the first Board of Trustees: John D. Rockefeller, of New York. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., of New York. Frederick T. Gates, of Montclair, N, J. Harry Pratt Judson, of Chicago, 111. Simon Flexner, of New York. Starr J. Murphy, of Montclair, N. J. Jerome D. Greene, of New York. Wickliffe Rose, of Washington, D. C. Charles 0. Heydt, of Montclair, N. J. To the foregoing number have been added by election the following Trustees: Charles W. Eliot, of Cambridge, Mass.1 8 A. Barton Hepburn, of New York. G Appended hereto are the detailed reports of the Secretary and the Treasurer of the Rockefeller Foundation and of the Director General of the International Health Commission, JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., President. 1 Elected January 21, 1914. 9 Elected March 18, 1914. 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation To the President of the Rockefeller Foundation: Sir:— I have the honor to submit herewith my report as Secretary of the Rockefeller Foundation for the period May 14, 1913, to December 31, 1914. -

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W. -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER AND THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER XVEDUCATION XV THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO William Rainey Harper, 1882, Baldwin and Harvey Photographic Artists, Chicago. I I “BROAD AND CHRISTIAN IN THE FULLEST SENSE” William Rainey Harper and the University of Chicago INTRODUCTION e meet today at a noteworthy moment in our history. The College has now met and surpassed the enrollment W goals established by President Hugo F. Sonnenschein in 1996, and we have done so while increasing our applicant pool, our selectivity, and the overall level of participation by the faculty in the College’s instructional programs. Many people—College faculty, staff, alumni, and students—have contributed to this achievement, and we and our successors owe them an enormous debt of gratitude. I am particularly grateful to the members of the College faculty—as I know our students and their families are—for the crucial role that you played as teachers, as mentors, as advisers, and as collaborators in the academic achievements of our students. The College lies at the intellectual center of the University, an appropriate role for the University’s largest demographic unit. We affirm academic excellence as the primary norm governing all of our activities. Our students study all of the major domains of human knowledge, and they do so out of a love of learning and discovery. They undertake general and specialized studies across the several disciplines, from the humanities to the natural sciences and mathematics to the social sciences and beyond, This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 25, 2005. -

Doing Scholarship from a Faith Perspective: Reading the Sacred As Sacred Encounter

Doing Scholarship from a Faith Perspective: Reading the Sacred as Sacred Encounter Ismael Velasco When Moses, walking through the desert, came upon Mount Horeb, he beheld God speaking from within a flame of fire amidst a burning bush, ablaze, yet unconsumed, and calling out to him: “Moses! Moses!” To which he unhesitatingly replied: “Here am I.” Whereupon he was commanded, “Draw not nigh hither: put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place wherein thou standest is holy ground.”1 Today no man can claim to have seen the burning bush; but the voice of the Transcendent calls still in accents of absolute authority in the Holy Writ of the religions of the world. A reader who would venture to such formidable and self-sufficient mountains, whereon millions hear, even today, the voice of God or truth supreme, and seek with reason and study to gain a glimmer of that spot wherein Moses stood, such a one, believer or not, would do well, like Moses, to halt for thought, and first put off his sandals in respect, else reverence, for the sheer magnitude of his purposed subject. For in approaching scripture, it will be readily acknowledged, one is dealing with a text extraordinary in the most palpable way. No other text outside of scripture carries so profoundly in every word a million and a million life-trajectories; no other category of text has so deeply shaped or shapes today so many identities in such far-reaching ways. To say “this word means this” of a part of sacred scripture is, wittingly or unwittingly, to pronounce on the meaning of unnumbered lives whose hopes and yearnings are, were or will be built around a given understanding of the very words one is pronouncing on - peripheral or irrelevant though they might seem to the commentator. -

“Teaching at a University of a Certain Sort” 2

“ T E A C H I N G A T A U N I V E R S I T Y O F A CERTAIN SORT” E D U C A T I O N A T T H E UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OVER THE PAST CENTURY J o h n W . B o y e r OCCASIONAL PAPERS O N H I G H E R EDUCATION XXI XXITHE COLLEGE O F T H E UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Ralph W. Tyler, Chief Examiner, Board of Examinations, 1938 –1953 “TEACHING AT A UNIVERSITY O F A C E R T A I N S O R T ” Education at the University of Chicago over the Past Century INTRODUCTION he College begins this academic year with slightly more than 5,300 students. Our first-year class of 1,416 stu- T dents plus 42 transfer students will sustain the College at its current size. The talent, creativity, and ambition of our students; the extraordinary pool of applicants from which they were chosen; and their eagerness to participate with all of us in the en- terprise of learning at the College should make us confident that the academic year that is just underway will be stimulating and rewarding. The Admissions data we have heard today are one of several ways to measure the achievements of our students. We might also cite the schol- arships and fellowships they have won in the past decade—including 14 Rhodes Scholarships, 117 Fulbrights, and 36 Goldwaters. Less familiar names are also on the list: In 2011 two students won Woodrow Wilson– Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellowships for Aspiring Teachers of Color, supporting enrollment in graduate education programs that lead to a master’s degree and teaching certification; and a third student won a Jack Kent Cooke Foundation Graduate Arts Award, supporting three years of This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 18, 2011. -

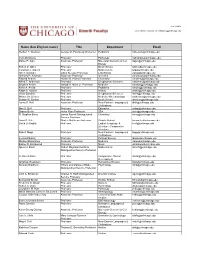

(A to Z by Last Name) Title Department Email Herbert T

As of 12.20.18 Corrections? Contact [email protected] Name (A to Z by last name) Title Department Email Herbert T. Abelson George M. Eisenberg Professor Pediatrics [email protected] Cyril Abrahams Professor Pathology [email protected] Daniel P. Agin Associate Professor Molecular Genetics & Cell [email protected] Biology Robert Z. Aliber Professor Booth School [email protected] Jonathan L. Alperin Professor Mathematics [email protected] Albert Alschuler Julius Kreeger Professor Law School [email protected] Anthony P. Amarose Associate Professor Genetics [email protected] Edward Anders Horace B. Horton Professor Chemistry [email protected] Alfred T. Anderson Professor Geophysical Sciences [email protected] Stephen Archer Harold H. Hines Jr. Professor Medicine [email protected] Rene A. Arcilla Professor Pediatrics [email protected] Ralph A. Austen Professor History [email protected] Victor Barcilon Professor Geophysical Sciences [email protected] Michael A. Becker Professor Medicine-Rheumatology [email protected] Selwyn W. Becker Professor Booth School [email protected] Lanny D. Bell Associate Professor Near Eastern Languages & [email protected] Civilizations Max S. Bell Professor Education [email protected] Sharon Berlin Helen Ross Professor SSA [email protected] R. Stephen Berry James Franck Distinguished Chemistry [email protected] Service Professor Hans D. Betz Shailer Matthews Professor Divinity School [email protected] David Bevington Professor English Language & [email protected] Literature; Comparative Literature Robert Biggs Professor Near Eastern Languages & [email protected] Civilizations Leonard Binder Professor Political Science [email protected] Michael Blackstone Associate Professor Medicine [email protected] Easley R. Blackwood Professor Music [email protected] Spencer Bloch Robert Maynard Hutchins Mathematics [email protected] Distinguished Service Professor R. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President Scrapbooks 1889-1943

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President Scrapbooks 1889-1943 © 2012 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 4 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Series I: News Clippings 5 Series II: Communications 6 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.OFCPRESSCRAPBOOK Title University of Chicago. Office of the President. Scrapbooks Date 1889-1943 Size 51.5 linear feet (34 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains scrapbooks compiled by the University of Chicago Office of the President. They contain news clippings related to the University, its founding, and its staff and leadership, and collections of official communications issued by the President's office. The collection spans the years 1889-1943, with the bulk of the material dating from 1908 to 1910. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Office of the President. Scrapbooks, Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Historical Note On September 18, 1890, William Rainey Harper was elected by the Board of Trustees as the first President of the University of Chicago. President Harper assumed office on July 1, 1891. The University has had 13 presidents in total: • William Rainey Harper – 1891-1906 • Harry Pratt Judson – 1907-1923 • Ernest DeWitt Burton – 1923-1925 • Max Mason – 1925-1928 3 • Robert Maynard Hutchins – 1929-1951 • Lawrence Kimpton – 1951-1960 • George W. -

Building the Chicago School MICHAEL T

American Political Science Review Vol. 100, No. 4 November 2006 Building the Chicago School MICHAEL T. HEANEY University of Florida JOHN MARK HANSEN University of Chicago he Chicago School of Political Science, which emerged at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, is widely known for its reconception of the study of politics as a scientific endeavor T on the model of the natural sciences. Less attention has been devoted to the genesis of the school itself. In this article, we examine the scientific vision, faculty, curriculum, and supporting institutions of the Chicago School. The creation of the Chicago School, we find, required the construction of a faculty committed to its vision of the science of politics, the muster of resources to support efforts in research and education, and the formation of curriculum to educate students in its precepts and methods. Its success as an intellectual endeavor, we argue, depended not only on the articulation of the intellectual goals but also, crucially, on the confluence of disciplinary receptiveness, institutional opportunity, and entrepreneurial talent in support of a science of politics. central force in the evolution of political sci- After World War II, the apostles of the Chicago ence, like other of the social sciences, has been School—–those who pursued doctoral studies at Athe incorporation of the methods of the nat- Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s—–moved to faculty ural sciences. During the 1920s and 1930s, a group of positions at leading universities around the United scholars advocating the development of a “science” of States: V.O. -

LEADING DEEPLY: a HEROIC JOURNEY TOWARD WISDOM and TRANSFORMATION Prepared By

LEADING DEEPLY: A HEROIC JOURNEY TOWARD WISDOM AND TRANSFORMATION RICHARD WARM A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2011 This is to certify that the dissertation entitled: LEADING DEEPLY: A HEROIC JOURNEY TOWARD WISDOM AND TRANSFORMATION prepared by Richard Warm is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership and Change. Approved by: Carolyn Kenny, Ph.D., Chair date Laura Morgan Roberts, Ph.D. , Committee Member date Jonathan Reams, Ph.D., Committee Member date Donna Ladkin, Ph.D., External Reader date Copyright 2011 Richard Warm All rights reserved Dedication I dedicate this work to my father, who even after I have studied leadership for 5 years, is still the best example and role model of a leader that I know. I miss you. And I dedicate this work to my mother, who probably does not realize that I am the writer (and cook) that I am today because of her. Thank you. Acknowledgments My very deepest gratitude goes to my teacher and guide, mentor and friend, Sword Made of Clouds, for always believing in me, always letting me at least try to do things my way, and knowing somehow everything would work out. It has been a great privilege working with you the past five years, Carolyn, and I probably would not be here without you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. You are the best!! Also my appreciation and respect goes to Laurien, Al, and the entire faculty.