The Marriage Go-Round: an Exploratory Study of Multiple Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc. Attachment Style and Adjustment to Divorce

Scientific Information System Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Sagrario Yárnoz-Yaben Attachment Style and Adjustment to Divorce The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol. 13, núm. 1, mayo, 2010, pp. 210-219, Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17213039016 The Spanish Journal of Psychology, ISSN (Printed Version): 1138-7416 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative The Spanish Journal of Psychology Copyright 2010 by The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2010, Vol. 13 No. 1, 210-219 ISSN 1138-7416 Attachment Style and Adjustment to Divorce Sagrario Yárnoz-Yaben Universidad del País Vasco (Spain) Divorce is becoming increasingly widespread in Europe. In this study, I present an analysis of the role played by attachment style (secure, dismissing, preoccupied and fearful, plus the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance) in the adaptation to divorce. Participants comprised divorced parents (N = 40) from a medium- sized city in the Basque Country. The results reveal a lower proportion of people with secure attachment in the sample group of divorcees. Attachment style and dependence (emotional and instrumental) are closely related. I have also found associations between measures that showed a poor adjustment to divorce and the preoccupied and fearful attachment styles. Adjustment is related to a dismissing attachment style and to the avoidance dimension. Multiple regression analysis confirmed that secure attachment and the avoidance dimension predict adjustment to divorce and positive affectivity while preoccupied attachment and the anxiety dimension predicted negative affectivity. -

Training Video #1 - How Married Couples Learn to Be Sponsors/Mentors

Training Video #1 - How married couples learn to be sponsors/mentors. If you are a marriage educator, adapt these ideas to your situation. INTRODUCTION THE VIDEO and ADDITIONAL RESOURCES WHAT IS A "SPONSOR COUPLE" AND WHAT DO THEY DO? HOW DO YOU KNOW WHETHER YOU CAN DO THIS? THE DESIGN OF THE PROGRAM PREPARING YOURSELVES…BEFORE YOU MEET WITH AN ENGAGED COUPLE LEARNING TO USE EACH OTHER’S STRENGTHS DECIDING WHERE TO MEET MINIMIZING DISTRACTIONS SNACKS & BREAKS PRAYER DEALING WITH QUESTIONS SCHEDULING THE SESSIONS FIRST SESSION THE FOUR RULES INTRODUCING THE CANDLE AND PRAYER DIALGOGUE / DISCUSSION WITH THE ENGAGED COUPLE DEALING WITH UNEXPECTED CHALLENGES RESOURCES A TYPICAL SESSION WITH THE ENGAGED FOLLOW UP CONCLUSION OF VIDEO ONE INTRODUCTION [TRAINER: So, if you are here today because you think have the “perfect marriage,” I would say that you are the one couple I would encourage to find another ministry. You need to be a “normally nutty” couple to able to help those just beginning the journey of Christian marriage. While these books (For Better and For Ever) provide really good information, it is your own life experience through the good times and terrible times of marriage that will help engaged couples learn to survive and grow as married couples. People getting married today are scared that they might not be successful. It does not help them to meet “the perfect couple.” They need to know that normal “nutty” couples …like them…can survive the challenges of marriage. ] NARRATOR: Welcome to the ministry of marriage preparation. · The task of the church is to teach people how to live the gospel of Jesus. -

Pdf, 147.07 KB

The crew visits the lush FOREST MOON OF GRENLYND and find that shrinking down just makes bigger problems. DAR pulls a PLECK. A marriage is consummated. [Dramatic science-fiction music plays, like the text crawl at the beginning of Star Wars] NARRATOR: The period of civil war has ended. The rebels have defeated the evil Galactic Monarchy and established the harmonious Federated Alliance. Now, ambassador Pleck Decksetter and his intrepid crew travel the farthest reaches of the galaxy to explore astounding new worlds, discover their heroic destinies, and meet weird bug creatures and stuff. This is [echoing] Mission to Zyxx! [Music becomes more dramatic and trumpet-y, then fades away] PLECK: Hey, Dar? DAR: Yeah, what’s up? PLECK: Um-- [quietly] Can I ask you, like, a personal question? DAR: No. PLECK: Okay. [pause] Hey, C-53? C-53: [whirrs as if turning to face Pleck] Yes? PLECK: What species is Dar? C-53: Ambassador Decksetter, I believe you just asked Dar whether you could ask her a personal question. PLECK: [very quietly] You don’t need-- you can just keep quiet-- C-53: And she responded in the negative. PLECK: Okay. That’s-- yep. C-53: I would feel I was invading her privacy to reveal that information. PLECK: Okay, yeah. No, we don’t need to talk-- I get that now. We don’t need to talk-- I was just curious. C-53: Very well. PLECK: [clears throat] Hey, Bargie? BARGIE: No. PLECK: [laughs] No, I’m not gonna-- I would not-- I get it, we’re not, I’m-- C-53: [moderately amused] But were you about to ask? PLECK: That doesn’t-- that’s irrelevant at this point. -

I-IOW to CI-IOOSE a HUSBAND 'I-J "-Lopkins You Will Pick a Good Husband If You Decide for MARY ALDEN Finds It to Return Or

~bitauo 6unba!' Vtribune ''-a!' 20,1928 5 HOW TO CHOOSE A • f}31V' Do RIS WEBSTER.a.nd HUSBAND - By Doris Webster AND Mary Alden Hopkins (Continued from page jO'UT.) KEY NUMBER 25. to be in trouble. Remember how difficult 0. woman I-IOW TO CI-IOOSE A HUSBAND 'I-J "-lOPKINS You will pick a good husband if you decide for MARY ALDEN finds it to return or. exchange a man after she has married him. yourself. You are in danger of being unduly in- '. fluenced by some one who speaks firmly but not KEY NUMBER 5. wisely to you. Quietly select your own hats, hUI!- Can you ha ve harmonious business or social rela- You may not be a large woman physically, but, band, and cooking utensils. Give in to others if There' s Just One tions with uncongenial people? you are mentally. You are the kind that runs or- you wish on politics, religion, and such matters. Have you' changed your views on politics, re- ganizatione efficiently and sees to it that every You will make a good wife and a happy one for ligion, or morals within the Iast five years? one in the organization knows his duty and does it. 'almost any man who shows you a good deal of Man for You, Whether You will not change, so you must be careful to attention. GROUP 4. marry the right man-one who admires your ap- KEY NUMBER 34. Do you desire an "addre88 of distinction "t preciation of the really worth while things in life You are by no means ready to marry, for at pres- and who will 110t find your missionary spirit trying. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 1345736 Musicals often demonstrate the cultural aspects of the periods in which they were written Dowd, James M., M.A. The American University, 1991 Copyright ©1991 by Dowd, James M. -

The Lived Experience of Ambiguous Marital Separation a Dissertation

The Lived Experience of Ambiguous Marital Separation A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sarah Ann Crabtree IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser: Steven M. Harris June 2018 © 2018 Sarah A. Crabtree i Acknowledgements It is not lost on me that I am here because of the efforts and contributions of so many people. I recognize the privilege associated with entering a doctoral program, and while I do not want to minimize my own hard work, I cannot claim to have gotten here entirely on my own volition. I must acknowledge how fortunate I am to have had the support of so many people along the way. First, I want to thank my family. I am grateful for the ways you cheered me on, sent notes of encouragement, checked on how things were progressing, and offered unending patience and understanding through the entirety of this process. Thank you, as well, for affording me opportunities through of your financial support of my education. Having access to a quality education opened innumerable doors, which subsequently opened even more. It is hard to quantify what has come from all the ways you have invested in me and this process. Thank you, thank you, thank you. I also want to acknowledge several instrumental mentors who helped me envision a future I would not have dared dream for myself. Dr. Leta and Phil Frazier, Dr. Mary Jensen, Dr. Steve Sandage, Dr. Cate Lally, Dr. Carla Dahl, Tina Watson Wiens – thank you for imagining for and with me, for helping me find a home in my own skin, and for encouraging me to dream big. -

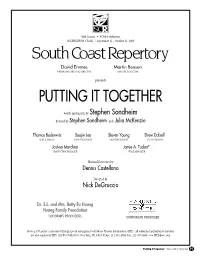

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

Standard Symbols for Genograms

Standard Symbols for Genograms Male Female Birth DateAge Death Family Secret ‘41- ‘82- 1943-2002 23 59 Heterosexual written on written an X through Symbol left above inside Age at death in box of symbol symbol Death date on right above symbol Gay/Lesbian Bisexual Location & Significant Person who Annual Income Institutional has lived in Immigration Connection 2 + cultures Boston Transgender People $100,000 ‘72- ‘41- ‘41- Pet Man to Woman woman to man written above birth & death date AA m 1970 Therapist Therapist Couple Secret Committed Marriage Relationship Affair Relationship m 1970 Rel 95, LT 97 Affair ‘95 LT ‘95 LT = Living Together Marital Separation Divorce Divorce and Remarriage m ‘90, s 95-96, s 96, d ‘97 remar ’00, rediv 02 met ‘88,, m ‘90 s ’95 m ‘90 s ’95 d ‘97 m ‘03 m ‘05 Children: List in birth order beginning with the oldest on left ‘97-97 -‘99 -‘01 LW 98-99 A ‘97 ‘92- ‘94- ‘95- ‘03- ‘03- ‘04- ‘04- ‘05- Stillbirth Abortion 13 11 10 Miscarriage Biological Foster Adopted Twins Identical Pregnancy Child Child Child Twins Symbols Denoting Addiction, and Physical or Mental Illness Physical or Physical or Smoker Psychological illness Psychological illness S in remission Obesity O Alcohol or Drug abuse In Recovery from Language Problem alcohol or drug abuse L Suspected alcohol In recovery from Serious mental and or drug abuse substance abuse and physical problems mental or Physical problems and substance abuse Symbols Denoting Interactional Patterns between People “spiritual” connection Close DistantClose-Hostile Focused On Fused Hostile Fused-Hostile Cutoff Cutoff Repaired Physical AbuseEmotional Abuse Sexual Abuse Caretaker Annual income is written $100,000 $28,000 just above the 1943-2002 ‘53- birth & death date. -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

CHOOSING of a BRIDE Los Angeles, CA March 29, 1965 Vol

SERMONS BY REV. W. M. BRANHAM "... in the days of the voice... " Rev. 10:7 CHOOSING OF A BRIDE Los Angeles, CA March 29, 1965 Vol. 65, No. 22 Introduction The compiler of the work, A. David Mamalis, recognized that all sermons are public domain, belonging to the people. There is NO claim of copyright on the sermon text. The copyright applies to the verso side of the title page; and only in the design of the classification system of all interrelations of the text to the volume, volume number, paging, paragraphing, or any identification of the text by utilizing the copyrighted classification system. The purpose of such copyright is to preserve the work for the design of indexes, and other support reference materials, for the study of the last days' message. Permission is given for anyone to print and distribute this booklet, provided it is done free of charge. Any changes made to the electronic file that this booklet is distributed in constitute a violation of international copyright law. Instructions for printing this booklet in its proper format can be found in the Printing FAQ on our website at www.thefreeword.com. We pray that the Holy Spirit will make the messages alive to those who are called to be conformed to the image of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. www.thefreeword.com Licensed Internet Publisher If you would like more information on the ministry of Rev. William M. Branham, download additional sermons or have questions of a spiritual nature, please refer to our website at: www.thefreeword.com Copyright by A.