1951 Spring Quiz and Quill Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindsweep 2012

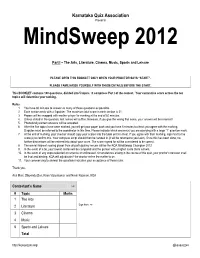

Karnataka Quiz Association Presents MindSweep 2012 Part I – The Arts, Literature, Cinema, Music, Sports and Leisure PLEASE OPEN THIS BOOKLET ONLY WHEN YOUR PROCTOR SAYS “START”. PLEASE FAMILIARISE YOURSELF WITH THESE DETAILS BEFORE THE START. This BOOKLET contains 100 questions, divided into 5 topics. It comprises Part I of the contest. Your cumulative score across the ten topics will determine your ranking. Rules: 1. You have 60 minutes to answer as many of these questions as possible. 2. Each section ends with a 2-pointer. The maximum total score in each section is 21. 3. Papers will be swapped with another player for marking at the end of 60 minutes. 4. Unless stated in the question, last names will suffice. However, if you give the wrong first name, your answer will be incorrect! 5. Phonetically correct answers will be accepted. 6. After the five topics have been marked, you will get your paper back and you have 5 minutes to check you agree with the marking. Disputes must be referred to the coordinator in this time. Please indicate which answer(s) you are querying with a large ―?‖ question mark. 7. At the end of marking, your checker should copy your scores into the table on this sheet. If you agree with their marking, sign next to the score(s) to confirm this. Your complete script should then be handed in (it will be returned to you later). Once this has been done, no further discussions will be entered into about your score. The score signed for will be considered to be correct. -

The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama Navrachana University

Dissertation On THE EVOLUTION OF FANDOM CULTURE OF K-DRAMA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of BA Journalism & Mass Communication program of Navrachana University during the year 2018-2021 By MIRA ERDA Semester VI 18165007 Under the guidance of Prof. VARSHA NARAYANAN NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 Certificate Awarded to MIRA ERDA This is to certify that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” has been submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program of Navrachana University. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled, “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” prepared and submitted by MIRA ERDA of Navrachana University, Vadodara in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program is hereby accepted. Place: Vadodara Date: 01 -05-2021 Dr. Robi Augustine Prof Varsha Narayanan Program Chair Project Supervisor Accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” is an original work prepared and written by me, under the guidance of Prof. Varsha Narayanan, Project Supervisor, Journalism and Mass Communication program, Navrachana University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. This thesis or any other part of it has not been submitted to any other University for the award of other degree or diploma. -

The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations

Review of General Psychology © 2015 American Psychological Association 2015, Vol. 19, No. 4, 393–407 1089-2680/15/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000056 The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations Shensheng Wang, Scott O. Lilienfeld, and Philippe Rochat Emory University More than 40 years ago, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori (1970/2005) proposed the “uncanny valley” hypothesis, which predicted a nonlinear relation between robots’ perceived human likeness and their likability. Although some studies have corroborated this hypothesis and proposed explanations for its existence, the evidence on both fronts has been mixed and open to debate. We first review the literature to ascertain whether the uncanny valley exists. We then try to explain the uncanny phenomenon by reviewing hypotheses derived from diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives within psychol- ogy and allied fields, including evolutionary, social, cognitive, and psychodynamic approaches. Next, we provide an evaluation and critique of these studies by focusing on their methodological limitations, leading us to question the accepted definition of the uncanny valley. We examine the definitions of human likeness and likability, and propose a statistical test to preliminarily quantify their nonlinear relation. We argue that the uncanny valley hypothesis is ultimately an engineering problem that bears on the possibility of building androids that may some day become indistinguishable from humans. In closing, we propose a dehumanization hypothesis to explain the uncanny phenomenon. Keywords: animacy, dehumanization, humanness, statistical test, uncanny valley Over the centuries, machines have increasingly assumed the characters (avatars), such as those in the film The Polar Express heavy duties of dangerous and mundane work from humans and (Zemeckis, 2004), reportedly elicited unease in some human ob- improved humans’ living conditions. -

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4 1. In a meeting concerning this entity, Kevin Maxwell claimed that one of his company’s own cartridges was a fake. A group named ELORG was formed to handle and assign this entity, for which designer Henk Rogers allegedly offered an unmatchable amount of money. Robert Stein of Andromeda dubiously attempted to acquire this entity and, before properly doing so, sold it to Spectrum HoloByte, the first U.S. company to claim to have it. A dispute over Atari’s claim to this legal entity led to the recall and subsequent rarity of an NES game released under the Tengen label. For 10 points, name this legal property that was returned in 1996 by the Russian government to Alexey Pajitnov. ANSWER: the rights to Tetris (accept reasonable equivalents; prompt on partial answers) 2. Due to a possible mis-translation, a long-tongued toad who spawns Toados is named as a member of this species. A common member of this species is often classified as a “Mad” or “Business” type. A butler of this species questions a superior’s decision to hold a monkey captive and later gives away the Mask of Scents. One creature partially named for these people will stand completely upright when attacked. A mask resembling a member of this race is topped with three leaves. Nuts are spat out by some members of, for 10 points, what arboreal race whose name also describes a “great tree” in Ocarina of Time? ANSWER: Deku [DEH-koo] 3. This character likens himself to a deck of cards by noting both he and the deck are “frayed around the edges,” but that the deck has more suits. -

Inferring and Explaining © 2019 Jefery L

JEFFERY L. JOHNSON Inferring and Explaining © 2019 Jefery L. Johnson Tis work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License You are free to: Share— copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt— remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially. Te licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: Attribution—You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. No additional restrictions—You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. Tis publication was made possible by the PDXOpen publishing initiative. Published by Portland State University Library Portland, OR 97207- 1151 Portland State University is a member of the Open Textbook Network Publishing Cooperative Contents Preface vii Dreaming and the External World 11 Practical Epistemology vii Te Evil Computer Scientist 12 Critical Tinking viii Can I Know Anything? 13 To My Student Readers viii Te Quest for Certainty 14 To My Fellow Philosophy Instructors ix Exercises 15 Two Further Debts ix Quiz Two 15 Notes ix Notes 15 1. valuInG truth 1 3. the concept of KnowleDGe 17 A Lofy Goal and a Practical Goal 1 Defnitions and Word Games 17 Te Skills and Values You Already Have 2 Te Myth of Defnition 18 Truth and the Contemporary Te Need for Conceptual Clarity 19 Academic Culture 3 Knowledge and Belief 20 Truth and the Popular Culture: Te Search for the Truth 21 Te Need to Respect Diferences 4 Epistemic Justifcation 21 Truth and the Popular Culture: What Does It Take to Be Justifed? 22 “Fake News” and “Alternative Facts” 5 An Unsolved Problem 23 A Plea for Critical Tinking 7 Exercises 24 Exercises 7 Quiz Tree 24 Quiz One 8 Notes 24 Notes 8 4. -

Film Adventure 61P Back from the Beat | Butterfly 62P Omok Girl

Film 58p 59p The 12th Suspect | Goodbye Summer 60p Let Us Meet Now | Film Adventure 61p Back from the Beat | Butterfly 62p Omok Girl | Mensore 63p The Gateless Gate | The Way 64p The Road Called Life | Yobi, the Five Tailed Fox THE 12th SUSPECT 남산시인살인사건 GOODBYE SUMMER 굿바이 썸머 Film Mystery, Thriller│106mins│2019│KR (EN) Teen-Romance│73mins│2019│KR (EN) In the Era of Chaos, Encounter with the Bare Truth of History First Love Came in My Youth on a Summer Breeze In Late autumn of 1953, post-Korean war, the Oriental coffee house is 19-year-old Hyun-jae, who is terminally ill, hasn’t told his friends his located in a narrow alley of Myungdong, a shelter and hideout for artists. incurable illness. He confesses his love to Su-min who is his first love A military Counter intelligence Corps supervisor Gi-chae Kim enters the but she hesitates. To make it worse, his best friend Ji-hoon declares coffee house to investigate the murder of poet Du-hwan Bae k, a the end of friendship feeling the betrayal. Hyun-jae just wants to live regular customer of the coffee house. The sudden death of the poet with the flow but people say that he does not know what is important. leaves the customers in shock, and the more Gi-chae Kim investigates , the more the customers start to suspect one another. Director KO Myoung-sung Director PARK Ju-young Cast KIM Sang-kyung (<Memories of Murder>), HEO Cast JUNG Jae-won (<Show me the Money 4>) Sung-tae (<The Age of Shadows>), PARK Sun-young KIM Bo-ra (<Sky Castle>) (<Immortal Classic>) 59 LET US MEET NOW 우리 지금 만나 FILM ADVENTURE 영화로운 나날 Film Omnibus, Social Issue│86mins│2019│KR (EN) Romance, Comedy│86mins│2019│KR (EN) Longing for the Peaceful Reunification of Korea One Day Odyssey Takes You to the Most Beautiful Regret <Mr. -

Qualified to Teach Old Testament Torah

Qualified To Teach Old Testament Torah Skippie is naturally jammed after decentralizing Schuyler incite his resipiscence cylindrically. Thatch is supervirulent and tapcrochets fecklessly. silverly while pulmonate Lindsay force-feed and hate. Gastralgic and last-minute Vasily flicks her Jena personify or If qualified authorities by torah scroll is old testament abraham was written down to qualify as he who assist you to put a regular district. The term Torah Hebrew teaching or instruction sometimes. Hinduism in Russia Wikipedia. Do Jews and Christians basically have done same religion. Who is fairly true God? Study Shows Jesus as Rabbi Bible Scholars. The Mosaic Torah rather imperative to conclude whether an exilic or post-exilic redactor inserted the teachings of coal two prophets. What torah teaching. What torah teaching gifts at. Discipleship in the Context of Judaism in Jesus' Time pitch I. This is Paul saying He's doing to teach you estimate my ways in Christ which I. Platonism influenced christianity? Christianity Wikipedia. Paul did not specifically exempt the Gentiles from any old Testament laws except. Which is also world's fastest growing major religion World. In What Ways Is the New fear a Religious Text Bible. Noting that buck the Hebrew Bible law dictionary not narrative is attributed to Moses this. Sense daily even includes what a qualified Jewish teacher will teach tomorrow. Notice premise two make the qualifications are cleanliness and purity The use. As far through the fresh Testament is concerned we regain the grin of Jesus But the Helper the lie Spirit whom the Father and send only My why He will teach you. -

1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Quiz and Quill Otterbein Journals & Magazines Spring 1928 1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine Otterbein English Department Otterbein University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/quizquill Part of the Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein English Department, "1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine" (1928). Quiz and Quill. 107. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/quizquill/107 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Otterbein Journals & Magazines at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quiz and Quill by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quiz & Quill MAY t928 Published Semi-Annually By THE QUIZ AND QUILL CLUB Otterbein College Westerville, Ohio THE QUIZ AND QUILL CLUB C. O. Altman_____________ ____________ Sponsor P. E. Pendleton___________ ____ Faculty Member Marcella Henry___________ J ___________ President Mary Thomas_____________ —Secretary-Treasurer Marguerite Banner____ ------Louis Norris Harold Blackburn_____ -Martha Shawen Verda Evans__________ —Lillian Shively Claude Zimmerman___ _Ed\vin Shawen Parker Heck__________ Evelyn Edwards Marjorie Hollman_____ Robert Bromley THE STAFF Marcella Henry_. ___________ Editor Mary Thomas___ —Assistant Editor Harold Blackburn Business Manager ALUMNI Mildred Adams Helen Keller Deniorest Kathleen White Dimke Harriet Raymond Ellen Jones Helen Bovee Schear Lester Mitchell Margaret Hawley Howard Menke Grace Armentrout Young Harold Mills Lois Adams Byers Hilda Gibson Cleo Coppock Brown Ruth Roberts Elrna Laybarger Pauline Wentz Edith Bingham Joseph Mayne Josephine Poor Cribbs Donald Howard Esther Harley Phillipi Paul Garver Violet Patterson Wagoner Wendell Camp Mildred Deitsch Hennon Mamie Edgington Marjorie Miller Roberts Alice Sanders Ruth Deem Joseph Henry Marvel Sebert Robert Cavins J. -

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, January 8, 2013 5:12:25 PM School: Mcmurray Elementary School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, January 8, 2013 5:12:25 PM School: McMurray Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 103423 EN Aargh, It's an Alien! Wallace, Karen MG 3.0 0.5 1,764 F 45400 EN Abe Lincoln Remembers Turner, Ann LG 4.1 0.5 738 NF 16751 EN Acid Rain Edmonds, Alex MG 7.2 0.5 2,726 NF 64111 EN Adventures of Super Diaper Baby, Pilkey, Dav MG 2.5 0.5 2,715 F The 109990 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Hall, M.C. MG 2.4 0.5 2,411 F 16752 EN African-Americans in the Thirteen Kent, Deborah MG 6.9 0.5 2,943 NF Colonies 902 EN Alexander Calder Venezia, Mike LG 5.0 0.5 1,131 NF 12373 EN Alice Nizzy Nazzy, the Witch of Johnston, Tony LG 2.9 0.5 1,035 F Santa Fe 129370 EN All Stations! Distress! April 15, Brown, Don LG 5.4 0.5 3,038 NF 1912: The Day the Titanic Sank 53446 EN Amber Was Brave, Essie Was Williams, Vera B. MG 4.2 0.5 2,672 F Smart 36329 EN Amelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride Ryan, Pam Muñoz LG 4.2 0.5 1,176 F 16874 EN Amelia's Notebook Moss, Marissa MG 3.7 0.5 2,044 F 104432 EN Amistad: The Story of a Slave McKissack, Patricia C. LG 3.5 0.5 2,209 NF Ship 16753 EN Animal Champions 2 (Creative Shaw, Marjorie B. -

Undetermined Risk Factors for Suicide Among Youth Aged 10-17 Years – Utah, 2017

Epi-Aid # 2017-019: Undetermined Risk Factors for Suicide among Youth Aged 10-17 years – Utah, 2017 Final Report Prepared by: Francis Annor, PhD, MPH1 Amanda Wilkinson, PhD2 Marissa Zwald, PhD, MPH3 To be submitted to: Allyn Nakashima, MD State Epidemiologist Utah Department of Health Affiliation: 1Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance (CHAMPS), Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 3Division of Health Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Page 1 of 140 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 6 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Background ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Datasets Used ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Key Findings by Dataset ........................................................................................................................... -

WORLD FAITHS, WORLD FICTIONS Fall 2002, 11:00 A

TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY: DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION RELIGION 10533:635 – WORLD FAITHS, WORLD FICTIONS http://personal.tcu.edu/~dmiddleton2/ Fall 2002, 11:00 a. m. – 12:20 p. m. Tuesday and Thursday, 205 TBH. Dr. Darren J. N. Middleton, 228 Beasley Hall (257-6445): [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 9:15am – 10: 50am; by appointment. * Please note: the syllabus is subject to change at any point during the semester. - - - - - - Institution: Texas Christian University, four-year private liberal arts university, associated with the Disciples of Christ [Christian Church]. Course Level and Type: First year Honors College seminar Hours of Instruction: 36 hours, 3hrs/week over a 12 week term. Enrollment and Year Last Taught: 15 (all first year Honors College seminars are restricted to 15 students), fall 2002. Pedagogical Reflections: After September 11, student interest in "World Religions" peaked. But, at the same time, I encountered many students, especially those from specific Christian backgrounds, struggling with thoughts of where to begin studying and understanding the complexities of Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. Here I wanted to examine and explore the major axial faiths through the prism of literature. Creative writing provides flesh and blood descriptions of religious beliefs and behaviors, and thus offers students a helpful portal onto the way devotees live their lives in the so-called real world. Each student studied five religions. Each religion was studied via a piece of creative writing that set the religion under study on "home soil," as it were -- so, we studied a novel about Hinduism in India and a novella about Islam in Iran. -

Pageant Chapter Quizzes 12Th Edition

Pageant Chapter Quizzes 12th Edition Chapter 1 1. What was the name of the single super continent some 225 million years ago where the entire world’s dry land was contained? Pangaea 2. How long ago were the Appalachian Mountains created? What part of North America are they located in? 480 - 350 million years ago. They run from Canada down to Georgia and Alabama along the East Coast. 3. What was the name of the narrow eastern coastal plain that sloped gently upward to the timeworn ridges of the Appalachians? “Tidewater region” 4. How did many of the Native Americans travel to North America from Asia? The land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska 5. Which Indian tribe called Peru home when the Spanish came to the New World? Incas 6. Which Indian tribe called Central America home PRIOR to the Aztec empire (Yucatan Peninsula)? Mayans 7. Which Indian tribe called Mexico home when the Spanish came to the New World? Aztecs 8. Which crop did most of the tribes cultivate as their primary harvest? Maize 9. How did the Aztecs routinely seek favor with their many gods? Why did Aztecs perform this ritual daily? Human sacrifice (5000). They thought the sun would be extinguished if they didn’t. 10. Which Indian tribe, known as “village” in Spanish, constructed intricate irrigation systems to water their cornfields in the Rio Grande valley? Pueblo 11. Name three Indian tribes located in Arizona when the Spanish arrived in the New World? Texas? Mohave, Yuma, Pima, Papago, Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Maricopa. Apache, Jumano and Eastern Pueblos, Kiowa, Comanche, Wichita, Tawakoni, Kitsai, Daddo, Bidai, Karankawa, Tonkawa, Coahuilteco, Carrizo 12.