1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindsweep 2012

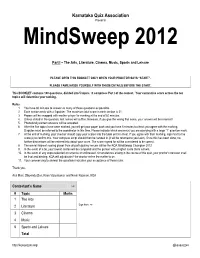

Karnataka Quiz Association Presents MindSweep 2012 Part I – The Arts, Literature, Cinema, Music, Sports and Leisure PLEASE OPEN THIS BOOKLET ONLY WHEN YOUR PROCTOR SAYS “START”. PLEASE FAMILIARISE YOURSELF WITH THESE DETAILS BEFORE THE START. This BOOKLET contains 100 questions, divided into 5 topics. It comprises Part I of the contest. Your cumulative score across the ten topics will determine your ranking. Rules: 1. You have 60 minutes to answer as many of these questions as possible. 2. Each section ends with a 2-pointer. The maximum total score in each section is 21. 3. Papers will be swapped with another player for marking at the end of 60 minutes. 4. Unless stated in the question, last names will suffice. However, if you give the wrong first name, your answer will be incorrect! 5. Phonetically correct answers will be accepted. 6. After the five topics have been marked, you will get your paper back and you have 5 minutes to check you agree with the marking. Disputes must be referred to the coordinator in this time. Please indicate which answer(s) you are querying with a large ―?‖ question mark. 7. At the end of marking, your checker should copy your scores into the table on this sheet. If you agree with their marking, sign next to the score(s) to confirm this. Your complete script should then be handed in (it will be returned to you later). Once this has been done, no further discussions will be entered into about your score. The score signed for will be considered to be correct. -

Trompe L'oeil and Financial Risk in The

Carrington Bowles (publisher). The Bubblers Medley, or a Sketch of the Times: Being Europe’s Memorial for the Year 1720, 1721. Engraving. © Trustees of the British Museum. Carrington Bowles (publisher). The Bubblers Medley, or a Sketch of the Times: Being Europe’s Memorial for the Year 1720, 1721. Engraving. © Trustees of the British Museum. 6 https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00287 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/grey_a_00287 by guest on 28 September 2021 Trompe L’oeil and Financial Risk in the Age of Paper MAGGIE M. CAO Three hundred years ago, in the summer of 1720, the bursting of the South Sea Bubble marked the first recorded stock market crash. The ensuing financial crisis provided great fodder for the British satirical press, which took to caricaturing both the company’s gullible victims and manipulative executives. Among the rich material trove of that historical moment are a pair of prints published by the London shop of John Bowles and Carington Bowles.1 Titled The Bubblers Medley, or A Sketch of the Times: Being Europe’s Memorial for the Year 1720, the prints depict a scattered array of paper artifacts in collage-like, random fashion. Sheets overlap and furl on the edges, creating a trompe l’oeil effect that encourages viewers to misread the artwork as a collection of the actual ephemera it represents. Trompe l’oeil–style prints like these, also called medley prints, developed in 1700s London, and in the century that followed they enjoyed episodic popularity, often at moments of fiscal uncertainty. As Mark Hallett argues, this print type, like other satirical images referencing public discourses and debates, was meant to be read as well as viewed. -

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It the Harvard Community Has

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Citation Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Accessed July 1, 2016 4:22:42 AM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant

Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Christman, Victoria Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 08:36:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195502 ORTHODOXY AND OPPOSITION: THE CREATION OF A SECULAR INQUISITION IN EARLY MODERN BRABANT by Victoria Christman _______________________ Copyright © Victoria Christman 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Victoria Christman entitled: Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Professor Susan C. Karant Nunn Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Alan E. Bernstein Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Helen Nader Date: 17 August 2005 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It the Harvard Community Has

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Accessed February 18, 2015 9:54:33 PM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://www.nap.edu/24781 SHARE Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use DETAILS 380 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-45954-9 | DOI: 10.17226/24781 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Richard J. Bonnie, Morgan A. Ford, and Jonathan K. Phillips, Editors; Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Opioid Abuse; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Health and FIND RELATED TITLES Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use PAIN MANAGEMENT AND THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC BALANCING SOCIETAL AND INDIVIDUAL BENEFITS AND RISKS OF PRESCRIPTION OPIOID USE Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Prescription Opioid Abuse Richard J. Bonnie, Morgan A. Ford, and Jonathan K. Phillips, Editors Board on Health Sciences Policy Health and Medicine Division A Consensus Study Report of PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. -

The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama Navrachana University

Dissertation On THE EVOLUTION OF FANDOM CULTURE OF K-DRAMA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of BA Journalism & Mass Communication program of Navrachana University during the year 2018-2021 By MIRA ERDA Semester VI 18165007 Under the guidance of Prof. VARSHA NARAYANAN NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 Certificate Awarded to MIRA ERDA This is to certify that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” has been submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program of Navrachana University. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled, “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” prepared and submitted by MIRA ERDA of Navrachana University, Vadodara in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program is hereby accepted. Place: Vadodara Date: 01 -05-2021 Dr. Robi Augustine Prof Varsha Narayanan Program Chair Project Supervisor Accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” is an original work prepared and written by me, under the guidance of Prof. Varsha Narayanan, Project Supervisor, Journalism and Mass Communication program, Navrachana University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. This thesis or any other part of it has not been submitted to any other University for the award of other degree or diploma. -

The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations

Review of General Psychology © 2015 American Psychological Association 2015, Vol. 19, No. 4, 393–407 1089-2680/15/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000056 The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations Shensheng Wang, Scott O. Lilienfeld, and Philippe Rochat Emory University More than 40 years ago, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori (1970/2005) proposed the “uncanny valley” hypothesis, which predicted a nonlinear relation between robots’ perceived human likeness and their likability. Although some studies have corroborated this hypothesis and proposed explanations for its existence, the evidence on both fronts has been mixed and open to debate. We first review the literature to ascertain whether the uncanny valley exists. We then try to explain the uncanny phenomenon by reviewing hypotheses derived from diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives within psychol- ogy and allied fields, including evolutionary, social, cognitive, and psychodynamic approaches. Next, we provide an evaluation and critique of these studies by focusing on their methodological limitations, leading us to question the accepted definition of the uncanny valley. We examine the definitions of human likeness and likability, and propose a statistical test to preliminarily quantify their nonlinear relation. We argue that the uncanny valley hypothesis is ultimately an engineering problem that bears on the possibility of building androids that may some day become indistinguishable from humans. In closing, we propose a dehumanization hypothesis to explain the uncanny phenomenon. Keywords: animacy, dehumanization, humanness, statistical test, uncanny valley Over the centuries, machines have increasingly assumed the characters (avatars), such as those in the film The Polar Express heavy duties of dangerous and mundane work from humans and (Zemeckis, 2004), reportedly elicited unease in some human ob- improved humans’ living conditions. -

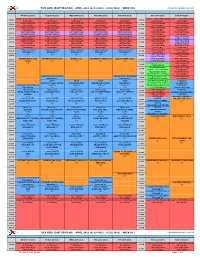

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Master Ref List Cover Page

ELNEC END-OF-LIFE NURSING EDUCATION CONSORTIUM SuperCore Curriculum FACULTY GUIDE Master Reference List Copyright City of Hope and American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2007. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) Project is a national end –of-life educational program administered by City of Hope (COH) and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) designed to enhance palliative care in nursing. The ELNEC Project was originally funded by a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation with additional support from funding organizations (the National Cancer Institute, Aetna Foundation, California HealthCare Foundation, and Archstone Foundation). Further information about the ELNEC Project can be found at www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC. ELNEC: End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Master Reference List Administration on Aging. (2006). Older population by age: 1900 to 2050. Retrieved June 30, 2008 from http://www.aoa.gov./prof/statistics/online_stat_data/popage2050.xls Alvarez, O., Kalinski, C., Nusbaum, J., Hernandez, L., Pappous, E., Kyriannis, C., et al. (2007). Incorporating wound healing strategies to improve palliation (symptom management) in patients with chronic wounds. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10(5), 1161-89. American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM). (2001). The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain (Joint consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society & American Society of Addiction Medicine). Retrieved August 29, 2008 from: http://www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/opioids.htm American Association of Colleges of Nurses. (1997). A peaceful death [Report from the Robert Wood Johnson End-of-Life Care Roundtable]. Washington, DC: Author. American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. -

Jonathan Zittrain's “The Future of the Internet: and How to Stop

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4 1. In a meeting concerning this entity, Kevin Maxwell claimed that one of his company’s own cartridges was a fake. A group named ELORG was formed to handle and assign this entity, for which designer Henk Rogers allegedly offered an unmatchable amount of money. Robert Stein of Andromeda dubiously attempted to acquire this entity and, before properly doing so, sold it to Spectrum HoloByte, the first U.S. company to claim to have it. A dispute over Atari’s claim to this legal entity led to the recall and subsequent rarity of an NES game released under the Tengen label. For 10 points, name this legal property that was returned in 1996 by the Russian government to Alexey Pajitnov. ANSWER: the rights to Tetris (accept reasonable equivalents; prompt on partial answers) 2. Due to a possible mis-translation, a long-tongued toad who spawns Toados is named as a member of this species. A common member of this species is often classified as a “Mad” or “Business” type. A butler of this species questions a superior’s decision to hold a monkey captive and later gives away the Mask of Scents. One creature partially named for these people will stand completely upright when attacked. A mask resembling a member of this race is topped with three leaves. Nuts are spat out by some members of, for 10 points, what arboreal race whose name also describes a “great tree” in Ocarina of Time? ANSWER: Deku [DEH-koo] 3. This character likens himself to a deck of cards by noting both he and the deck are “frayed around the edges,” but that the deck has more suits.