The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting the Uncanny Valley Theory: Developing and Validating an Alternative to the Godspeed Indices

Computers in Human Behavior 26 (2010) 1508–1518 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Computers in Human Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh Revisiting the uncanny valley theory: Developing and validating an alternative to the Godspeed indices Chin-Chang Ho, Karl F. MacDorman * Indiana University School of Informatics, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA article info abstract Article history: Mori (1970) proposed a hypothetical graph describing a nonlinear relation between a character’s degree Available online 8 June 2010 of human likeness and the emotional response of the human perceiver. However, the index construction of these variables could result in their strong correlation, thus preventing rated characters from being Keywords: plotted accurately. Phase 1 of this study tested the indices of the Godspeed questionnaire as measures Affective appraisal of humanlike characters. The results indicate significant and strong correlations among the relevant indi- Embodied agents ces (Bartneck, Kulic´, Croft, & Zoghbi, 2009). Phase 2 of this study developed alternative indices with non- Human–robot interaction significant correlations (p > .05) between the proposed y-axis eeriness and x-axis perceived humanness Psychometric scales (r = .02). The new humanness and eeriness indices facilitate plotting relations among rated characters of Social perception varying human likeness. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Plotting emotional responses to humanlike characters interpersonal warmth (Asch, 1946; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007; Rosenberg, Nelson, & Vivekananthan, 1968), which is also strongly Mori (1970) proposed a hypothetical graph describing a nonlin- correlated with other important measures, such as comfortability, ear relation between a character’s degree of human likeness and communality, sociability, and positive (vs. -

Digital Humans on the Big Screen

news Technology | DOI:10.1145/3403972 Don Monroe Digital Humans on the Big Screen Motion pictures are using new techniques in computer-generated imagery to create feature-length performances by convincingly “de-aged” actors. RTIFICIAL IMAGES HAVE been around almost as long as movies. As com- puting power has grown and digital photography Ahas become commonplace, special ef- fects have increasingly been created digitally, and have become much more realistic as a result. ACM’s Turing Award for 2019 to Patrick M. Hanrahan and Edwin E. Cat- mull reflected in part their contribu- tions to computer-generated imagery (CGI), notably at the pioneering anima- tion company Pixar. CGI is best known in science fic- tion or other fantastic settings, where audiences presumably already have suspended their disbelief. Similarly, exotic creatures can be compelling In Ang Lee’s 2019 action movie Gemini Man, Will Smith (right) is confronted by a younger when they display even primitive hu- clone of himself (left). This filmmakers went through a complicated process to “de-age” man facial expressions. Increasingly, Smith for the younger role. however, CGI is used to save money on time, extras, or sets in even mun- actors. Artificial intelligence also in- “In many ways it felt less about a visual dane scenes for dramatic movies. creasingly will augment the labor-inten- effect and more like we were creating a re- To represent principal characters, sive effects-generation process, allowing ality and aiming to work out exactly how however, filmmakers must contend filmmakers to tell new types of stories. the human face works, operates, but also with our fine-tuned sensitivity to facial how it ages over time,” added Stuart Ad- expressions. -

AUDIENCE PERCEPTION of EXAGGERATED MOTION on REALISTIC ANIMATED CREATURES by Mackenzie Hammer

AUDIENCE PERCEPTION OF EXAGGERATED MOTION ON REALISTIC ANIMATED CREATURES by Mackenzie Hammer A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computer Graphics Technology West Lafayette, Indiana August 2019 2 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Prof. Nicoletta Adamo, Chair Department of Computer Graphics Technology Prof. Andrew Buchanan Department of Computer Graphics Technology Prof. Esteban Garcia Department of Computer Graphics Technology Prof. Dan Triplett Department of Computer Graphics Technology Approved by: Dr. Colin Gray Head of the Graduate Program Prof. Nicoletta Adamo Head of the Graduate Program 3 To my parents, brother, sister, and fiancé. For their continuous love and support in my pursuit to study Animation, and for the patience they had to listen to the many ramblings of a passionate artist along the way. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to gratefully acknowledge my professors and thesis committee members for their insightful guidance, encouragement, and contribution to the completion of this work. 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 8 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

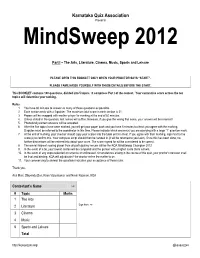

Mindsweep 2012

Karnataka Quiz Association Presents MindSweep 2012 Part I – The Arts, Literature, Cinema, Music, Sports and Leisure PLEASE OPEN THIS BOOKLET ONLY WHEN YOUR PROCTOR SAYS “START”. PLEASE FAMILIARISE YOURSELF WITH THESE DETAILS BEFORE THE START. This BOOKLET contains 100 questions, divided into 5 topics. It comprises Part I of the contest. Your cumulative score across the ten topics will determine your ranking. Rules: 1. You have 60 minutes to answer as many of these questions as possible. 2. Each section ends with a 2-pointer. The maximum total score in each section is 21. 3. Papers will be swapped with another player for marking at the end of 60 minutes. 4. Unless stated in the question, last names will suffice. However, if you give the wrong first name, your answer will be incorrect! 5. Phonetically correct answers will be accepted. 6. After the five topics have been marked, you will get your paper back and you have 5 minutes to check you agree with the marking. Disputes must be referred to the coordinator in this time. Please indicate which answer(s) you are querying with a large ―?‖ question mark. 7. At the end of marking, your checker should copy your scores into the table on this sheet. If you agree with their marking, sign next to the score(s) to confirm this. Your complete script should then be handed in (it will be returned to you later). Once this has been done, no further discussions will be entered into about your score. The score signed for will be considered to be correct. -

Tales of Dread

Zlom1_2019_Sestava 1 5.4.19 8:01 Stránka 65 WINNER OF THE FABIAN DORSCH ESA ESSAY PRIZE TALES OF DREAD MARK WINDSOR ‘Tales of dread’ is a genre that has received scant attention in aesthetics. In this paper, I aim to elaborate an account of tales of dread which (1) effectively distinguishes these from horror stories, and (2) helps explain the close affinity between the two, accommodating borderline cases. I briefly consider two existing accounts of the genre – namely, those of Noël Carroll and of Cynthia Freeland – and show why they are inadequate for my purposes. I then develop my own account of tales of dread, drawing on two theoretical resources: Freud’s ‘The “Uncanny”’, and Tzvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic. In particular, I draw on Freud to help distinguish tales of dread from horror stories, and I draw on Todorov to help explain the fluidity between the genres. I argue that both horror stories and tales of dread feature apparent impossibilities which are threatening; but whereas in horror stories the existence of the monster (the apparent impossibility) is confirmed, tales of dread are sustained by the audience’s uncertainty pertaining to preternatural objects or events. Where horror monsters pose an immediate, concrete danger to the subject’s physical well-being, these preternatural objects or events pose a psychological threat to the subject’s grasp of reality. I In his book The Philosophy of Horror, Noël Carroll identifies a narrative genre that he calls ‘tales of dread’. Unlike horror stories, Carroll claims, tales of dread do not feature monstrous entities or beings, but rather a distinctive kind of preternatural event. -

Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance Sarah Lucie The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ACTING OBJECTS STAGING NEW MATERIALISM, POSTHUMANISM AND THE ECOCRITICAL CRISIS IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE by SARAH LUCIE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 SARAH LUCIE All rights reserved ii Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance by Sarah Lucie This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________________________________________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Chair of Examining Committee __________________________________________________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Erika Lin Edward Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance by Sarah Lucie Advisor: Peter Eckersall I investigate the material relationship between human and nonhuman objects in performance, asking what their shifting relations reveal about our contemporary condition. -

Neopastoral Artifacts and the Phenomenology of Environment in American Modernist Poetics

REFUSE TO RELIC: NEOPASTORAL ARTIFACTS AND THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF ENVIRONMENT IN AMERICAN MODERNIST POETICS Douglas ii Refuse to Relic: Neopastoral Artifacts and the Phenomenology of Environment in American Modernist Poetics Thesis format: Monograph by Jeffrey Daniel Douglas, B.A., B.Ed., M.A. Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate Studies McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario, Canada © Jeffrey D. Douglas 2013 Douglas iii Abstract Building on concepts of the pastoral, the picturesque, the “vernacular ruin,” and frontierism in an American context, this thesis explores the interest in ruin and commodity- oriented refuse within rural, wilderness, and what Leo Marx in The Machine in the Garden calls “middle ground” environments. Chapter one analyzes how “nature,” as both scenery and the natural environment removed from civilization, has been conceptualized as a place where human-made objects become repurposed through the gaze of the spectator. Theories surrounding gallery and exhibition space, as well as archaeological practices related to garbage excavation, are assessed to determine how waste objects, when wrested out of context, become artifacts of cultural significance. Chapter two turns to focus on the settler experience of the frontier in order to locate a uniquely American evolution of the interest in everyday waste objects. Because the frontier wilderness in American culture can be regarded as a site of transition and malleability, it is argued that the (mis)perception of object matter within this transitional space helped to shape modernist poetics and its association with everyday objects. Chapters three and four return to the rural and the pastoral to focus on Marx’s concept of the “middle ground,” borderlands of quasi-natural space that are located “somewhere ‘between,’ yet in a transcendent relation to, the opposing forces of civilization and nature” (23). -

Running Head: Weak Uncanny Valley for Controlled Face Images Virtual

Running head: Weak Uncanny Valley for Controlled Face Images Virtual Faces Evoke Only a Weak Uncanny Valley Effect: An Empirical Investigation with Controlled Virtual Face Images Jari Kätsyri1,2*, Beatrice de Gelder1, Tapio Takala2 1Department of Cognitive Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Netherlands 2Department of Computer Science, Aalto University, Finland *Correspondence: Jari Kätsyri, Department of Computer Science, P.O.Box 15400, FI-00076 Aalto, Finland. jari.katsyri (at) aalto.fi Preprint version 2019-09-04 Running head: Weak Uncanny Valley for Controlled Face Images Abstract The uncanny valley (UV) hypothesis suggests that increasingly human-like robots or virtual characters elicit more familiarity in their observers (positive affinity) with the exception of near- human characters that elicit strong feelings of eeriness (negative affinity). We studied this hypothesis in three experiments with carefully matched images of virtual faces varying from artificial to realistic. We investigated both painted and computer-generated (CG) faces to tap a broad range of human-likeness and to test whether CG faces would be particularly sensitive to the UV effect. Overall, we observed a linear relationship with a slight upward curvature between human-likeness and affinity. In other words, less realistic faces triggered greater eeriness in an accelerating manner. We also observed a weak UV effect for CG faces; however, least human-like faces elicited much more negative affinity in comparison. We conclude that although CG faces elicit a weak UV effect, this effect is not fully analogous to the original UV hypothesis. Instead, the subjective evaluation curve for face images resembles an uncanny slope more than a UV. Based on our results, we also argue that subjective affinity should be contrasted against subjective rather than objective measures of human-likeness when testing UV. -

Robots: Is the Uncanny Valley Real?

BBC - Future Robots: Is the uncanny valley real? http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20130901-is-the-uncan... 2 September 2013 Robots: Is the uncanny valley real? By Rose Eveleth Total recoil The uncanny valley concept states that we are unsettled by robots and models that look almost, but not quite human. (Copyright: Getty Images) For decades the golden rule in robotics has been that the more lifelike a creation, the more likely it crosses the line from cute to creepy. But questions are being raised as to whether this is really true. Mick Walters opens a door in his lab and points his computer’s camera towards the small, blurry, tan-coloured object he has just revealed. "This is Kaspar Two," he says. As the Skype connection catches up, an image of a robot in a baseball hat, a blue button-down shirt and striped socks appears. Kaspar Two is a robot child. He's not even on, just sitting slumped over. Even though the image is somewhat fuzzy, Kaspar Two is able to give me that feeling, that nagging sense of unease. "I must admit," says Walters, "when I first actually built Kaspar, I did think he was a bit uncanny." Kaspar has been created at University of Hertfordshire, UK to help children with autism understand how to read emotions and engage with other people, but it falls into what's often 1 of 4 09/03/2013 09:48 AM BBC - Future Robots: Is the uncanny valley real? http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20130901-is-the-uncan.. -

Evaluation of the Uncanny Valley in CG Characters

SBC - Proceedings of SBGames 2012 Computing Track – Full Papers Evaluation of the Uncanny Valley in CG Characters Laura M. Flach Vanderson Dill Christian Lykawka Rafael H. de Moura M´arcio S. Pinho FACIN/PUCRS Soraia R. Musse Virtual Reality Group Virtual Humans Simulation Lab FACIN/PUCRS FACIN/PUCRS Abstract To answer these questions, we proposed an evalu- ation methodology based on a questionnaire with This paper revisits the Uncanny Valley subject in subjects. First, we selected representative char- order to evaluate its effects on the perception of acters from recent and well known movies and characters that currently use computer graphics, games, and other characters that are unknown. animation and computer simulation. It is based In order to evaluate the public's empathy with on surveys that generated hundreds of samples the chosen characters, we conducted a two-stages and showed preliminary results about new criteria questionnaire. In the first stage we presented still and correlations regarding the familiarity of the images and, in the second stage, videos with the characters with the public. The analysis of famil- performance of the same characters in the same iarity in those characters showed great agreement scenes. with the original curve of the uncanny valley. Fu- ture enhancements are then suggested to add new As the results, more than two hundred of analysed dimensions to the original graph. samples leaded to conclusions that indicated the uncanny valley hypothesis is valid for CG char- acters. The following sections cover the related Keywords:: Uncanny Valley, Computer works on the subject, the model for evaluation Graphics, Modern Media, Movies, Games (including the details of both surveys), obtained results and final considerations. -

Philosophy for Children and Pragmatism Part I. the Uncanny History of Pragmatism

Philosophy for Children and Pragmatism Part I. The Uncanny History of Pragmatism Agora Philosophical Forum Handout by Soroush Marouzi 1. A Brief Overview of the Pragmatism-P4C Relation: - Pragmatism was born in 1867 in America - P4C as a social movement was initiated in the early 1970’s - Pragmatism, as a philosophical position, manifests itself in the educational method advocated by the proponents of the P4C movement - Hence, we shall start with an overview of pragmatism - The methodological sensitivities to explore pragmatist philosophies o Employing the intellectual biography approach to unfold the varieties of pragmatist notions 2. The Metaphysical Club: - The American pragmatists were struggling to build the ‘modern’ America after the Civil war. o A historical narrative of the club by Louis Menand (2001) - The objective of the club: Bring metaphysics down to earth; start with human experience - The Four Greats: Charles S. Peirce, William James, Oliver W. Holmes, and Chauncy Wright 2.1. Charles. S. Peirce (1839-1914): - Peirce was “the greatest American thinker ever” (Russell 1959, p 276). - Peirce invented pragmatism o Along with semiotics, mathematical logic, statistical economics, game-theoretic semantics, economics of science, propensity interpretation of probability, indeterministic metaphysics, falsification, abductive reasoning, etc. - Peirce’s works to be discussed in this workshop o On a New List of Categories (1867) o The Fixation of Belief (1877) o How to Make Our Ideas Clear (1878) 2.2. William James (1842-1910): - A charming man with a popular philosophy - He is known as the father of psychology in America. o In his Principles of Psychology (1890), he demarcated psychology from philosophy. -

The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama Navrachana University

Dissertation On THE EVOLUTION OF FANDOM CULTURE OF K-DRAMA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of BA Journalism & Mass Communication program of Navrachana University during the year 2018-2021 By MIRA ERDA Semester VI 18165007 Under the guidance of Prof. VARSHA NARAYANAN NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 Certificate Awarded to MIRA ERDA This is to certify that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” has been submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program of Navrachana University. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled, “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” prepared and submitted by MIRA ERDA of Navrachana University, Vadodara in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program is hereby accepted. Place: Vadodara Date: 01 -05-2021 Dr. Robi Augustine Prof Varsha Narayanan Program Chair Project Supervisor Accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” is an original work prepared and written by me, under the guidance of Prof. Varsha Narayanan, Project Supervisor, Journalism and Mass Communication program, Navrachana University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. This thesis or any other part of it has not been submitted to any other University for the award of other degree or diploma.