Trompe L'oeil and Financial Risk in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It the Harvard Community Has

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Citation Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Accessed July 1, 2016 4:22:42 AM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant

Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Christman, Victoria Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 08:36:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195502 ORTHODOXY AND OPPOSITION: THE CREATION OF A SECULAR INQUISITION IN EARLY MODERN BRABANT by Victoria Christman _______________________ Copyright © Victoria Christman 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Victoria Christman entitled: Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Professor Susan C. Karant Nunn Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Alan E. Bernstein Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Helen Nader Date: 17 August 2005 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It the Harvard Community Has

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Accessed February 18, 2015 9:54:33 PM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://www.nap.edu/24781 SHARE Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use DETAILS 380 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-45954-9 | DOI: 10.17226/24781 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Richard J. Bonnie, Morgan A. Ford, and Jonathan K. Phillips, Editors; Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Opioid Abuse; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Health and FIND RELATED TITLES Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use PAIN MANAGEMENT AND THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC BALANCING SOCIETAL AND INDIVIDUAL BENEFITS AND RISKS OF PRESCRIPTION OPIOID USE Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Prescription Opioid Abuse Richard J. Bonnie, Morgan A. Ford, and Jonathan K. Phillips, Editors Board on Health Sciences Policy Health and Medicine Division A Consensus Study Report of PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. -

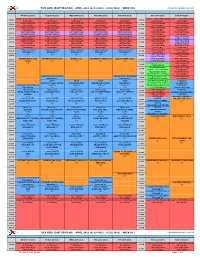

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Master Ref List Cover Page

ELNEC END-OF-LIFE NURSING EDUCATION CONSORTIUM SuperCore Curriculum FACULTY GUIDE Master Reference List Copyright City of Hope and American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2007. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) Project is a national end –of-life educational program administered by City of Hope (COH) and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) designed to enhance palliative care in nursing. The ELNEC Project was originally funded by a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation with additional support from funding organizations (the National Cancer Institute, Aetna Foundation, California HealthCare Foundation, and Archstone Foundation). Further information about the ELNEC Project can be found at www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC. ELNEC: End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Master Reference List Administration on Aging. (2006). Older population by age: 1900 to 2050. Retrieved June 30, 2008 from http://www.aoa.gov./prof/statistics/online_stat_data/popage2050.xls Alvarez, O., Kalinski, C., Nusbaum, J., Hernandez, L., Pappous, E., Kyriannis, C., et al. (2007). Incorporating wound healing strategies to improve palliation (symptom management) in patients with chronic wounds. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10(5), 1161-89. American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM). (2001). The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain (Joint consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society & American Society of Addiction Medicine). Retrieved August 29, 2008 from: http://www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/opioids.htm American Association of Colleges of Nurses. (1997). A peaceful death [Report from the Robert Wood Johnson End-of-Life Care Roundtable]. Washington, DC: Author. American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. -

Jonathan Zittrain's “The Future of the Internet: and How to Stop

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

JO WHITE and the 7 CAMPERS

JO WHITE and the 7 CAMPERS By Craig Sodaro Performance Rights To copy this text is an infringement of the federal copyright law as is to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for further scripts and licensing information. On all programs and advertising the author’s name must appear as well as this notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1989 by Eldridge Publishing Company Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://histage.com/jo-white-7-campers JO WHITE and the 7 CAMPERS -2- SYNOPSIS Hi-ho, hi-ho … uh-oh. A variety show competition tonight is Camp Wickeeup’s last chance to win the annual olympics against their arch rival, Camp Pine Cone. And winning these olympics isn’t just a game - it’s tradition! Trouble is, the Great Buffalo Wigwam was the cabin drawn to represent the camp. And the seven campers of the wigwam are not only sleepy, sneezy, grumpy, happy etc., but also completely inept! Luckily for the campers, Jo White, who would rather sing than whistle while she works, has escaped to their cabin. She was a maid for Mama Lu, one of the hottest rock stars around, but had to exit fast when an agent heard Jo singing and offered her a recording contract. Mama Lu, who has a somewhat fragile voice, is afraid Jo will be a bigger hit than she is. So she and her two back-up singers, Tiny and Bubbles, are out to get Jo. -

1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Quiz and Quill Otterbein Journals & Magazines Spring 1928 1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine Otterbein English Department Otterbein University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/quizquill Part of the Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein English Department, "1928 Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine" (1928). Quiz and Quill. 107. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/quizquill/107 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Otterbein Journals & Magazines at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quiz and Quill by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quiz & Quill MAY t928 Published Semi-Annually By THE QUIZ AND QUILL CLUB Otterbein College Westerville, Ohio THE QUIZ AND QUILL CLUB C. O. Altman_____________ ____________ Sponsor P. E. Pendleton___________ ____ Faculty Member Marcella Henry___________ J ___________ President Mary Thomas_____________ —Secretary-Treasurer Marguerite Banner____ ------Louis Norris Harold Blackburn_____ -Martha Shawen Verda Evans__________ —Lillian Shively Claude Zimmerman___ _Ed\vin Shawen Parker Heck__________ Evelyn Edwards Marjorie Hollman_____ Robert Bromley THE STAFF Marcella Henry_. ___________ Editor Mary Thomas___ —Assistant Editor Harold Blackburn Business Manager ALUMNI Mildred Adams Helen Keller Deniorest Kathleen White Dimke Harriet Raymond Ellen Jones Helen Bovee Schear Lester Mitchell Margaret Hawley Howard Menke Grace Armentrout Young Harold Mills Lois Adams Byers Hilda Gibson Cleo Coppock Brown Ruth Roberts Elrna Laybarger Pauline Wentz Edith Bingham Joseph Mayne Josephine Poor Cribbs Donald Howard Esther Harley Phillipi Paul Garver Violet Patterson Wagoner Wendell Camp Mildred Deitsch Hennon Mamie Edgington Marjorie Miller Roberts Alice Sanders Ruth Deem Joseph Henry Marvel Sebert Robert Cavins J. -

Bee Gee News April 5, 1939

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-5-1939 Bee Gee News April 5, 1939 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "Bee Gee News April 5, 1939" (1939). BG News (Student Newspaper). 507. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/507 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. WELCOME TODAY PRESIDENT FRANK J. PROUT! Bee Gee News I.NTRA-SQUAD GRID GAME VOL. XXIII. BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY, APRIL 5, 1939 No. 26 ~ B. G. Orators Enter Pi Kappa Delta Swing-On The YM-YW TO CONDUCT Pitt U. Players Will Present Installment Plan EASTER SERVICE AT Speech Tourney At Kent State 7 A.M. THURSDAY 'Brother Rat' Here April 18th WILL COMPETE WITH Committees Start Student Ministers Moore HILARIOUS DRAMA And Long Will Have What Is A Hat, STUDENTS FROM SIX Making Plans For Charge Of Program And Why? SHOWS LIFE AMONG A colorful and inspiring Batter EASTERN STATES Sr. Week Program sunrise service has been planned by Tho dictionary defines a hal CADETS AT V. M. I. tho YM and YWCA for Thursday Seven Local Speakers as "a covering for the head," Play Will Be Spontored Long And Moore Head morning. April fl, from 7 to 7:4B in but this is inadequate and Inaeu- Leave Friday With Profs.