Model Curriculum on the Effective Medical Documentation of Torture and Ill-Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindsweep 2012

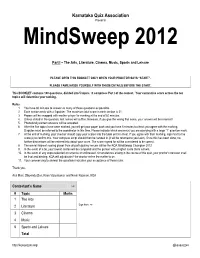

Karnataka Quiz Association Presents MindSweep 2012 Part I – The Arts, Literature, Cinema, Music, Sports and Leisure PLEASE OPEN THIS BOOKLET ONLY WHEN YOUR PROCTOR SAYS “START”. PLEASE FAMILIARISE YOURSELF WITH THESE DETAILS BEFORE THE START. This BOOKLET contains 100 questions, divided into 5 topics. It comprises Part I of the contest. Your cumulative score across the ten topics will determine your ranking. Rules: 1. You have 60 minutes to answer as many of these questions as possible. 2. Each section ends with a 2-pointer. The maximum total score in each section is 21. 3. Papers will be swapped with another player for marking at the end of 60 minutes. 4. Unless stated in the question, last names will suffice. However, if you give the wrong first name, your answer will be incorrect! 5. Phonetically correct answers will be accepted. 6. After the five topics have been marked, you will get your paper back and you have 5 minutes to check you agree with the marking. Disputes must be referred to the coordinator in this time. Please indicate which answer(s) you are querying with a large ―?‖ question mark. 7. At the end of marking, your checker should copy your scores into the table on this sheet. If you agree with their marking, sign next to the score(s) to confirm this. Your complete script should then be handed in (it will be returned to you later). Once this has been done, no further discussions will be entered into about your score. The score signed for will be considered to be correct. -

The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama Navrachana University

Dissertation On THE EVOLUTION OF FANDOM CULTURE OF K-DRAMA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of BA Journalism & Mass Communication program of Navrachana University during the year 2018-2021 By MIRA ERDA Semester VI 18165007 Under the guidance of Prof. VARSHA NARAYANAN NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY Vasna - Bhayli Main Rd, Bhayli, Vadodara, Gujarat 391410 Certificate Awarded to MIRA ERDA This is to certify that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” has been submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program of Navrachana University. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled, “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” prepared and submitted by MIRA ERDA of Navrachana University, Vadodara in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication program is hereby accepted. Place: Vadodara Date: 01 -05-2021 Dr. Robi Augustine Prof Varsha Narayanan Program Chair Project Supervisor Accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation titled “The Evolution of Fandom Culture of K-Drama” is an original work prepared and written by me, under the guidance of Prof. Varsha Narayanan, Project Supervisor, Journalism and Mass Communication program, Navrachana University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication. This thesis or any other part of it has not been submitted to any other University for the award of other degree or diploma. -

The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations

Review of General Psychology © 2015 American Psychological Association 2015, Vol. 19, No. 4, 393–407 1089-2680/15/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000056 The Uncanny Valley: Existence and Explanations Shensheng Wang, Scott O. Lilienfeld, and Philippe Rochat Emory University More than 40 years ago, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori (1970/2005) proposed the “uncanny valley” hypothesis, which predicted a nonlinear relation between robots’ perceived human likeness and their likability. Although some studies have corroborated this hypothesis and proposed explanations for its existence, the evidence on both fronts has been mixed and open to debate. We first review the literature to ascertain whether the uncanny valley exists. We then try to explain the uncanny phenomenon by reviewing hypotheses derived from diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives within psychol- ogy and allied fields, including evolutionary, social, cognitive, and psychodynamic approaches. Next, we provide an evaluation and critique of these studies by focusing on their methodological limitations, leading us to question the accepted definition of the uncanny valley. We examine the definitions of human likeness and likability, and propose a statistical test to preliminarily quantify their nonlinear relation. We argue that the uncanny valley hypothesis is ultimately an engineering problem that bears on the possibility of building androids that may some day become indistinguishable from humans. In closing, we propose a dehumanization hypothesis to explain the uncanny phenomenon. Keywords: animacy, dehumanization, humanness, statistical test, uncanny valley Over the centuries, machines have increasingly assumed the characters (avatars), such as those in the film The Polar Express heavy duties of dangerous and mundane work from humans and (Zemeckis, 2004), reportedly elicited unease in some human ob- improved humans’ living conditions. -

Medical Physical Examination in Connection with Torture

INTERNATIONAL • NATIONAL ADAPTATION │ MEDICAL • PSYCHOLOGICAL • LEGAL │ ENGLISH • FRENCH • SPANISH Reference Materials The Istanbul Protocol: International Guidelines for the Investigation and Documentation of Torture MEDICAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF ALLEGED TORTURE VICTIMS A Practical Guide to the Istanbul Protocol – for Medical Doctors 2004 This guide was written by the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) as part of the Istanbul Protocol Implementation Project, an initiative of Physicians for Human Rights USA (PHR USA), the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey (HRFT), the World Medical Association (WMA), and the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) THE ISTANBUL PROTOCOL IMPLEMENTATION PROJECT 2003 - 2005 © International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) Borgergade 13 P.O. Box 9049 DK-1022 Copenhagen K DENMARK Tel: +45 33 76 06 00 Fax: +45 33 76 05 00 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.irct.org ISBN 87-88882-71-3 The Istanbul Protocol: International Guidelines for the Investigation and Documentation of Torture MEDICAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF ALLEGED TORTURE VICTIMS A Practical Guide to the Istanbul Protocol - for Medical Doctors Ole Vedel Rasmussen, MD, DMSc Stine Amris, MD Margriet Blaauw, MD, MIH Lis Danielsen, MD, DMSc REFERENCE MATERIALS REGARDING THE USE OF THE ISTANBUL PROTOCOL: INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR THE INVESTIGATION AND DOCUMENTATION OF TORTURE The Istanbul Protocol is the first set of international guidelines for the investigation and documentation of torture. -

Istanbul Protocol

OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Geneva PROFESSIONAL TRAINING SERIES No. 8/Rev.1 Istanbul Protocol Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2004 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * Material contained in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, pro- vided credit is given and a copy of the publication containing the reprinted material is sent to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. HR/P/PT/8/Rev.1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.04.XIV.3 ISBN 92-1-154156-5 ISBN 92-1-116726-4 ISSN 1020-1688 Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Istanbul Protocol Submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 9 August 1999 PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS Action for Torture Survivors (HRFT), Geneva Amnesty International, London Association for the Prevention of Torture, Geneva Behandlungszentrum für Folteropfer, Berlin British Medical Association (BMA), London Center for Research and Application of Philosophy -

Reconstructing Ovicaprid Herding Pattern in Anatolian and Mesopotamian Settlements During the Bronze Age

Eurasian Journal of Anthropology Euras J Anthropol 4(1):23−35, 2013 Reconstructing ovicaprid herding pattern in Anatolian and Mesopotamian settlements during the Bronze Age Lubna Omar∗, A. Cem Erkman Department of Anthropology, Ahi Evran University, Kırşehir, Turkey Received July 12, 2013 Accepted December 30, 2013 Abstract This study focuses on examining caprine herding strategies during Early and Middle Bronze periods, throughout the analysis of the faunal materials that belong to Anatolian and upper Mesopotamian sites. The main argument of this paper is assessing the role of both environmental factors and socio-economic strategies in the development of caprine herding patterns. The zooarchaeological research methods which were applied on several faunal assemblages assisted us in evaluating the frequency of herded species in each settlement, the distribution of age groups and the variation of animal’s size. While conducting a comparative study among several archaeological sites situated in two distinctive geographical regions, will give us the chance to illustrate if environmental or socio-economic factors lead to the adaptation of certain herding patterns. Consequently we will able to shed new light on the developments of early urban societies. Keywords: Zooarchaeology, animal economy, Bronze Age, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, early urbanism Introduction Bronze Age era marks the beginning of the historical periods as human communities altered their subsistence strategies toward specialized economical system that paved the way for the raise of urbanism. Therefore, the study of the economic activities of various Bronze Age settlements located in the Anatolian plateau all the way to the southern Mesopotamian valley, will provide us with an exceptional opportunity to evaluate the background and the and fundamental elements of the early urban organizations. -

“Your Words, Lord, Are Spirit and Life.” Psalm 19:8

T H E M O T H E R C H U R C H O F T H E R O M A N C A T H O L I C D I O C E S E O F C O L U M B U S Since 1878 nourishing by Word and Sacrament all who enter this holy and sacred place. 212 East Broad Street + Columbus, Ohio 43215 + Phone: (614) 224-1295 + Fax: (614) 241-2534 www.saintjosephcathedral.org + www.cathedralmusic.org THIRD SUNDAY IN THE SEASON OF ORDINARY TIME ~ JANUARY 27, 2019 “Your words, Lord, are Spirit and life.” Psalm 19:8 INSIDE THIS BULLETIN Next Sunday, February 3, The Do’s and Don’ts of Reading the Bible immediately after all Masses 10 Ways to Fall in Love with the Bible the traditional Blessing of Throats will be available. Blessing of Throats: Feast of Saint Blaise Saint Francis de Sales: The Beauty of Devotion While not celebrated as such, February 3 is the traditional Feast of Saint Blaise. MONTHLY PRAYER INTENTION OF POPE FRANCIS: JANUARY SAINT JOSEPH CATHEDRAL 212 East Broad Street + Columbus, Ohio 43215 Evangelization – Young People Phone (614) 224-1295 + Fax (614) 241-2534 That young people, especially in Latin America, follow the example www.saintjosephcathedral.org of Mary and respond to the call of the Lord to communicate the joy www.cathedralmusic.org of the Gospel to the world. Check us out on www.facebook.com SCHEDULING MASS INTENTIONS + Most Reverend Frederick F. Campbell, D.D., Ph.D., One of the greatest acts of charity is to pray for the living and the Bishop of the Diocese of Columbus dead, and the greatest and most powerful prayer we have is the + Most Reverend James A. -

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 4 1. In a meeting concerning this entity, Kevin Maxwell claimed that one of his company’s own cartridges was a fake. A group named ELORG was formed to handle and assign this entity, for which designer Henk Rogers allegedly offered an unmatchable amount of money. Robert Stein of Andromeda dubiously attempted to acquire this entity and, before properly doing so, sold it to Spectrum HoloByte, the first U.S. company to claim to have it. A dispute over Atari’s claim to this legal entity led to the recall and subsequent rarity of an NES game released under the Tengen label. For 10 points, name this legal property that was returned in 1996 by the Russian government to Alexey Pajitnov. ANSWER: the rights to Tetris (accept reasonable equivalents; prompt on partial answers) 2. Due to a possible mis-translation, a long-tongued toad who spawns Toados is named as a member of this species. A common member of this species is often classified as a “Mad” or “Business” type. A butler of this species questions a superior’s decision to hold a monkey captive and later gives away the Mask of Scents. One creature partially named for these people will stand completely upright when attacked. A mask resembling a member of this race is topped with three leaves. Nuts are spat out by some members of, for 10 points, what arboreal race whose name also describes a “great tree” in Ocarina of Time? ANSWER: Deku [DEH-koo] 3. This character likens himself to a deck of cards by noting both he and the deck are “frayed around the edges,” but that the deck has more suits. -

Blessing Throats on the Feast of St. Blaise Unfortunately, What Is Known

Blessing Throats on the Feast of St. Blaise Unfortunately, what is known about the life of St. Blaise derives from various traditions. His feast day is celebrated in the East on Feb. 11 and in the West on Feb. 3 (although it was observed on Feb. 15 until the 11th century). All sources agree that St. Blaise was the Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia who suffered martyrdom under Licinius about A.D. 316. (Remember that Emperor Constantine had legalized the practice of Christianity in 313, but Licinius, his ally and co-emperor who had concurred in legalizing Christianity, betrayed him and began persecuting the Church. Constantine defeated Licinius in 324.) From here, we rely on the tradition which has been associated with our liturgical celebrations over the centuries, which does not necessarily preempt their veracity or accuracy. In accord with various traditions, St. Blaise was born to rich and noble parents, and received a Chris- tian education. He was a physician before being consecrated a bishop at a young age. Although such a statement seems terse, keep in mind that at that time the local community usually nominated a man to be a bishop based on his outstanding holiness and leadership qualities; he in turn was then exam- ined and consecrated by other bishops with the approval of the Holy Father. Therefore, St. Blaise must have been a great witness of our Faith, to say the least. During the persecution of Licinius, St. Blaise, receiving some divine command, moved from the town, and lived as a hermit in a cave. -

Proving Torture, Demanding the Impossible: Home Office Mistreatment of Medical Evidence

Proving Torture Demanding the impossible Home Office mistreatment of expert medical evidence November 2016 Freedom from Torture is the only UK-based human rights organisation dedicated to the treatment and rehabilitation of torture survivors. We do this by offering services across England and Scotland to around 1,000 torture survivors a year, including psychological and physical therapies, forensic documentation of torture, legal and welfare advice, and creative projects. Since our establishment in 1985, more than 57,000 survivors of torture have been referred to us, and we are one of the world’s largest torture treatment centres. Our expert clinicians prepare medico-legal reports (MLRs) that are used in connection with torture survivors’ claims for international protection, and in research reports, such as this. We are the only human rights organisation in the UK that systematically uses evidence from in-house clinicians, and the torture survivors they work with, to hold torturing states accountable internationally; and to work towards a world free from torture. To find out more about Freedom from Torture please visit www.freedomfromtorture.org Or follow us on Twitter@FreefromTorture Or join us on Facebook www.facebook.com/FreedomfromTorture Proving Torture Demanding the impossible Home Office mistreatment of expert medical evidence Cover photo: Survivor of Torture, by Jenny Matthews Title page photo: the scarred back of a 22-year-old Tamil man who is a survivor of sexual abuse and torture by Sri Lankan security forces while in detention ~ photo by Will Baxter FOREWORD Freedom from Torture must be congratulated for this excellent report. It clearly sheds light on what many of us working within the complex field of assessment of torture have been perturbed by for years - seemingly bizarre Home Office decisions in some asylum claims. -

Between the Lines

Between the Lines i of the Bible A MODERN COMMENTARY ON THE 613 COMMANDMENTS HERBERT S. GOLDSTEIN, D.D. Professor of Homiletics, Yeshiva University + Rabbi, West Side Institutional Synagogue, New York rown Publishers, Inc., New York 530th Commandment 306 532nd COMMANDMENT these days, usually make a on The Law Of The Beautiful ee special plea to the congregants ior Captive Woman the observance of the Torah, w ic We read in Deuteronomy, Chap. serves as a comfort to those in t ° ter 21, verse 10 and 11, “When thoy Great Beyond. “When Thou Shalt Do That Which Is Right In The Sight goest forth to battle against thine enemies .. and thou carriest them Of The Lord”. Again the Torah re- peats (See Chapter 19, verse 13) away captive’, verse 11, “and seest its exhortation against’ among the captives a woman of ism. goodly form, and thou hast a desire unto her, and wouldest take her to This commandment prevailed in thee to wife’. The Torah here makes th Israel at the time when the Jews settled there and also in Transjor- a concession to human nature dur. dania. ing wartime. The Israelite was to bring her into his house and have 531st OF THE 613 BIBLICAL her cut. her hair, leave her nails COMMANDMENTS grow long, substitute for the beauti- ‘Not To Work Nor To Seed In ful garment she wore, plain, simple The Rough Valley ones and remove all the jewelry and Concerning this we read in Deu- ornaments that she had for the pur- teronomy, Chapter 21, verse 4, “And pose of enticing, and permit her to the elders of that city shall bring cry for a month for her parents be- down the heifer unto a rough valley, cause of her enforced absence. -

Fathers Know Best? Christian Families in the Age of Asceticism

JACOBS AND KRAWIEC/FATHERS KNOW BEST 257 Fathers Know Best? Christian Families in the Age of Asceticism ANDREW S. JACOBS REBECCA KRAWIEC The lure of the early Christian family has grown strong in recent years: for cultural historians seeking the roots of “Western” civilization,1 for social historians trying to explore the lives of non-elite populations in the ancient world,2 and for religious historians still trying to answer the question, “What difference did Christianity make?”3 Although students of the earliest era of Christianity still press for more work to be done in their period,4 the steady growth of scholarship on the Roman family from 1. See, for instance, A History of the Family, 2 vols., ed. André Burguière et al. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1996), esp. Aline Rouselle’s essay “The Family Under the Roman Empire: Signs and Gestures,” 1:269–310; and more recently Jack Goody, The European Family: An Historico-Anthropological Essay, The Making of Europe (London: Blackwell, 2000), 27–44. 2. Family studies have notably drawn the attention of historians interested in the history of children, women, slaves, and gays. A few recent examples: Gillian Clark, Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Life-Styles (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993); eadem, “The Fathers and the Children,” in The Church and Childhood, ed. Diana Wood (London: Blackwell, 1994), 1–27; Chris Frilingos, “‘For My Child, Onesimus’: Paul and Domestic Power in Philemon,” JBL 119 (2000): 91–104; Bernadette Brooten, Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); John Boswell, Same- Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (New York: Villard Books, 1994).