Decoding Hardy's Architectural Metaphor in Jude the Obscure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-Łamanie (11).Indd

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. 11 2016, pp. 75–86 doi: 10.4467/20843941YC.16.005.6851 ROMEO AND JULIET: A NEW CONTEXT FOR VICTORY? Nic Panagopoulos National & Kapodistrian University of Athens Abstract: The contention of the present comparative study is that the closest Shakespearean work to Conrad’s Victory is not The Tempest, as has previously been thought, but Romeo and Juliet. Besides various thematic links between these two texts, also noted by Adam Gillon (1976), I argue that Victory and Romeo and Juliet are connected on the level of genre, plot, and characterization, with whole scenes in Conrad’s novel mirroring those in Shakespeare’s play. In conclusion I suggest that the striking similarities between the two works can either be explained by a conscious desire on Conrad’s part to imitate Shakespeare’s art, or by a kind of involuntary emulation, whereby the nov- elist had so far assimilated the Bard’s work as to follow it unconsciously while composing his own novel. Keywords: Conrad and Shakespeare, tragedy/comedy, mirroring, Victory, Romeo and Juliet, com- parative study, cryptomnesia In his famous extended essay “Joseph Conrad and Shakespeare,” the late Adam Gillon does a remarkable job of tracing the many textual and thematic parallels between Conrad’s major works and virtually the whole Shakespearean canon. He be- gins by pointing out that Conrad could have read The Two Gentlemen of Verona at the age of eight as his father was translating many of the Bard’s works into Polish around 1856. As is often the case, Shakespeare must have been one the fi rst writers that the young and impressionable Conrad was exposed to, and certainly one of the fi rst English writers in that category. -

AP English Literature Required Reading

Kerr High School AP English Literature Summer Reading 2019 Welcome to AP Literature! I’m fairly certain you are parched and thirsty for some juicy reading after a year of analyzing speeches and arguments, so let us jump right in. After months of deliberation and careful consideration, I have chosen several pieces from as far back as 429 BC Athens, to 1200 AD Scotland, venturing on to Africa 1800s, and finishing up in 20th century Chicago. Grab your literary passport and join me as we meet various tragic heroes and discover their tragic flaws and tragic mistakes. You will learn the difference between an Aristotelian tragic hero and a Shakespearean tragic hero, not to mention gain a whole bunch of insight into the human condition and learn some ancient Greek in the process. I made sure each piece is available in PDF online. If you choose to use the online documents, be certain you are able to annotate and have quick access to the annotated text for class discussions. The only AP 4 summer writing you will do is five reading record cards. Four of your reading record cards could include all of the required summer reading pieces. It is my expectation that you earnestly read, annotate, and ponder each of the required pieces and be ready to launch into discussion after your summer reading exam. Heavily annotated notes on the four attached tragic hero articles and your handwritten reading record cards will count as one major grade and are due Thursday, August 15, by 3:00 pm. Instructions for the reading record cards are attached. -

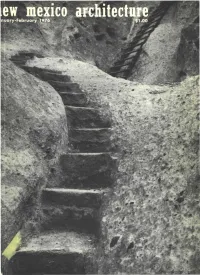

Complete Issue

Conerete Bloek & Sprayed Coating- a ~inning eOlDbination of beauty & silDplieity at lo~eost STAND RD CREGO CK WITH CEMENT LE E COAT AND SPRAYED-ON TE U ED INISH COAT • JERRY GOFFE PHOTO RUST TRACTOR COMPANY ELLISON-HAWKINS-VOGT 6' BYRNES, P.A. ARCH ITECTS ·ENGINEERS K. L. HOUSE CONSTRUCTION CO. GENERAL CONTRACTOR KENNETH P. THOMPSON CO., INC. MASONRY CONTRACTOR BILL C. CARROLL CO., INC. SPRAYED COATING "'\ For our reoders I"~, we wish 1976 to \'\'~" be rhapsodic, • thriving, abundant and eudaemonic. , '~-I4 ""_ """""' .----"''''''v~J col: 18 no. 1 jan. - feb. 1976 • new mexico architecture As we begin another year of New Mexico Architecture, it is appropri ate to remind our readers of the contribution made to our financial stability by the advertisers. It is their support which makes possible the production of the magazine. To all of these fine people the "staff" says a most sincere thank you! Space in New Mexico Architecture o DOD as a Resource for on Energy Ethic 10 Beginning on page lOis an arti - By Anthony C. Antoniades, AI.A, AI.P. cle by Anthony C. Antoniades, AlA, AlP, Associate Professor of Archi tecture at the University of Texas at Arlington. Professor Antoniades taught architecture at the Universi ty of New Mexico before moving to Index to Advertisers 18 Texas. It was during those years in our state that he developed a strong interest in and knowledge of the architectural heritage of New Mexi ico. Three articles by Antoniades hove appeared previously in NMA November/December 1971, Septem ber/October 1973 and July/August 1974. -

ALL MY SONS a Play in Three Acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller

ALL MY SONS a play in three acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller (Keller) Kate Keller (Mother) Chris Keller Ann Deever George Deever Dr. Jim Bayliss (Jim) Sue Bayliss Frank Lubey Lydia Lubey Bert Act One The back yard of the Keller home in the outskirts of an American town. August of our era. The stage is hedged on right and left by tall, closely planted poplars which lend the yard a secluded atmosphere. Upstage is filled with the back of the house and its open, unroofed porch which extends into the yard some six feet. The house is two stories high and has seven rooms. It would have cost perhaps fifteen thousand in the early twenties when it was built. Now it is nicely painted, looks tight and comfortable, and the yard is green with sod, here and there plants whose season is gone. At the right, beside the house, the entrance of the driveway can be seen, but the poplars cut off view of its continuation downstage. In the left corner, downstage, stands the four‐foot‐high stump of a slender apple tree whose upper trunk and branches lie toppled beside it, fruit still clinging to its branches. Downstage right is a small, trellised arbor, shaped like a sea shell, with a decorative bulb hanging from its forward‐curving roof. Carden chairs and a table are scattered about. A garbage pail on the ground next to the porch steps, a wire leaf‐burner near it. On the rise: It is early Sunday morning. Joe Keller is sitting in the sun reading the want ads of the Sunday paper, the other sections of which lie neatly on the ground beside him. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

"So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 3 Article 5 March 2012 Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office Frederick B. Jonassen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Frederick B. Jonassen, Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 853 (2012), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss3/5 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj KISS THE BOOK . YOU’RE PRESIDENT . : “SO HELP ME GOD” AND KISSING THE BOOK IN THE PRESIDENTIAL OATH OF OFFICE Frederick B. Jonassen* INTRODUCTION .................................................854 I. THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE OF “SO HELP ME GOD” AS HISTORICAL PRECEDENT IN THE PRESIDENT’S INAUGURATION ...................859 A. Washington’s “So Help Me God” in the Supreme Court ..........861 B. Newdow v. Roberts.......................................864 II. THE CASE AGAINST “SO HELP ME GOD”..........................870 A. The Washington Irving Recollection ..........................872 B. The Freeman Source ......................................874 C. Two Conjectural Arguments for “So Help Me God” Discredited ...879 D. One More Conjecture .....................................881 III. THE EVIDENCE THAT WASHINGTON KISSED THE BIBLE ..............885 A. First-Hand Accounts of the Biblical Kiss ......................885 B. The Subsequent Tradition ..................................890 1. Andrew Johnson......................................892 2. Ulysses S. Grant......................................892 3. Rutherford B. Hayes...................................893 4. James A. -

Idea and Execution in Jude the Obscure

Colby Quarterly Volume 9 Issue 10 June Article 3 June 1972 Idea and Execution in Jude the Obscure A. F. Cassis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 9, no.10, June 1972, p.501-509 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cassis: Idea and Execution in Jude the Obscure Colby Library Quarterly Series IX ,Tline 1972 No. 10 IDEA AND EXECUTION IN JUDE THE OBSCURE By A. F. CASSIS ~~T HERE HAS BEEN no such tragedy in fiction - on anything like the same lines - since he [Balzac] died," wrote Swin burne to Hardy after reading Jude the Obscure. Ten days after the publication of the novel, Hardy wrote to a "close friend": "You have hardly an idea how poor and feeble the book seems to me, as executed, beside the idea of it that I had formed in prospect."! Eight weeks later, to the same friend, he described it as "a mass of imperfections."2 Our purpose is to discover any "imperfections" in the tragedy and assess the "execution" in the light of the "idea." When he wrote the novel, Hardy believed that the greatest tragedy was "an excursion, a revelation of soul's unreconciled to life."3 This is why Jude, the only one of Hardy's characters whose life is traced from childhood to premature death, is en dowed with a sensitivity that amounts to a weakness and so feels "the pricks of life somewhat before his time." Dreams of aca demic distinction which develop into a ruling passion aggravate Jude's unreconcilement to life at Marygreen especially as Christ minster acquires a "tangibility, a permanence, a hold on his life."4 A blank refusal from one College brings his dreams to an abrupt end and the tragedy of "unfulfilled aims" comes to the forefront. -

Annual Report

Greeks Helping Greeks ANNUAL REPORT 2019 About THI The Hellenic Initiative (THI) is a global, nonprofi t, secular institution mobilizing the Greek Diaspora and Philhellene community to support sustainable economic recovery and renewal for Greece and its people. Our programs address crisis relief through strong nonprofi t organizations, led by heroic Greeks that are serving their country. They also build capacity in a new generation of heroes, the business leaders and entrepreneurs with the skills and values to promote the long term growth of Hellas. THI Vision / Mission Statement Investing in the future of Greece through direct philanthropy and economic revitalization. We empower people to provide crisis relief, encourage entrepreneurs, and create jobs. We are The Hellenic Initiative (THI) – a global movement of the Greek Diaspora About the Cover Featuring the faces of our ReGeneration Interns. We, the members of the Executive Committee and the Board of Directors, wish to express to all of you, the supporters and friends of The Hellenic Initiative, our deepest gratitude for the trust and support you have given to our organization for the past seven years. Our mission is simple, to connect the Diaspora with Greece in ways which are valuable for Greece, and valuable for the Diaspora. One of the programs you will read about in this report is THI’s ReGeneration Program. In just 5 years since we launched ReGeneration, with the support of the Coca-Cola Co. and the Coca-Cola Foundation and 400 hiring partners, we have put over 1100 people to work in permanent well-paying jobs in Greece. -

Of Desperate Remedies

Colby Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 1979 Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies Lawrence Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 15, no.3, September 1979, p.194-200 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Jones: Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Reme Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies by LAWRENCE JONES N THE autumn of 1884, Thomas Hardy was approached by the re I cently established publishing firm of Ward and Downey concerning the republication of his first novel, Desperate Remedies. Although it had been published in America by Henry Holt in his Leisure Hour series in 1874, the novel had not appeared in England since the first, anony mous publication by Tinsley Brothers in 1871. That first edition, in three volumes, had consisted of a printing of 500 (only 280 of which had been sold at list price). 1 Since that time Hardy had published eight more novels and had established himself to the extent that Charles Kegan Paul could refer to him in the British Quarterly Review in 1881 as the true "successor of George Eliot," 2 and Havelock Ellis could open a survey article in the Westminster Review in 1883 with the remark that "The high position which the author of Far from the Madding Crowd holds among contemporary English novelists is now generally recognized." 3 As his reputation grew, his earlier novels were republished in England in one-volume editions: Far from the Madding Crowd, A Pair of Blue Eyes, and The Hand ofEthelberta in 1877, Under the Greenwood Tree in 1878, The Return of the Native in 1880, A Laodicean in 1882, and Two on a Tower in 1883. -

Jude the Obscure

Colby Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 1991 Highways and Cornfields: Space and Time in the Narration of Jude the Obscure Janet H. Freeman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 27, no.3, September 1991, p.161-173 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Freeman: Highways and Cornfields: Space and Time in the Narration of Jude Highways and Cornfields: Space and Time in the Narration of Jude the Obscure by JAN ET H. FREE MAN A small slow voice rose from the shade ofthe fireside. as ifoul of the earth: "IfI was you, mother, I wouldn't marryfather!"father!"' It came from little Time, and they started, for they hadforgotten him. (V,4,223)(V,4,223j OTION is like breathing in Jude the Obscure: it is both a sign of life and a M sign of what life is like. As long as he lives, Jude Fawley never stops moving from place to place, sometimes deliberately, as when-"having always fancied himself arriving thus"l-he gets Ollt of the cart and makes his first entrance into Christminster walking on his own two feet; sometim€s uncon sciously, as when he and Arabella walk very far from horne on their first afternoon together; or impulsively, as when he and Sue, havingjust met, walk out to Lunlsdon in search of PhilJotson. -

Deal Simultaneously with Literary Forms. with the Chronological

.1\ * 4 411, 1, 1, 44' .041. 1 t i s 4 I .4 . DOCUMBN.T RESti.01E ED 033 114 . I. f g , .to O . 604 4 0,4 re 44 4. I 'to TE 001 533 By Sauer, Edwin H. I to *. t et°. Sequence and Uniformity in the High School Literature Program. o Metropolitan Detroit Bureau of School Studies. Inc.. Mich. ' Pub Date 28 Mar' 63 .., . 4 Y. 1* Note-16p.; Address before the 13th Annual English Conferenceof the Metropolitan Detroit Bureau of School Studies. Detroit. Michigan. EDRS Price MF -$025 HC -$0.90 Descriptors -Classic& Literature. Comedy. Curriculum. *Curriculum Design.Drama. *English. English Instruction. Literary Genres. Literary History. *Literature. Mythology. Novels.Poetry. Satire. *Secondary Education. *Sequential Programs. Thematic Approach. Tragedy A good. sequential literatureprogram for secondary school students should deal simultaneously with literary forms. with thechronological development of literature, and with broad themes of humanexperience. By employing the abundance of teaching aids.texts. and improved foreign translations available today.an imaginatively planned program can help studentsdiscover themselves as wellas become aware of their cultural heritage and rapidlychanging world. In grades 7-9. such a program should include mythology from all periodsand cultures. the literature of the great heroes from Agamemnonto Robert E. Lee. and the mysteryor cycle plays of the English Middle Ages. In grades 10-12.the lyric poem. satire and irony. the comic and tragic hero. the comedy ofmanners. the 'problem drama. the historical romance. the social novel, the novel of sensibility, the theme ofmovement, and such non-literary components as current eventsmay be covered. -

Tragedy and Transcendence: Tracing Tragedy from Early Modernity to Present William J

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Honors Theses Honors Projects 5-20-2012 Tragedy and Transcendence: Tracing Tragedy from Early Modernity to Present William J. Giancola '12 College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Giancola, William J. '12, "Tragedy and Transcendence: Tracing Tragedy from Early Modernity to Present" (2012). Honors Theses. 1. https://crossworks.holycross.edu/honors/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. TRAGEDY AND TRANSCENDENCE: TRACING TRAGEDY FROM EARLY MODERNITY TO PRESENT by William Giancola COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS Worcester, Massachusetts May, 2012 For Charles Flowers Table of Contents Introduction: Tragedy and Transcendence………………………………………………………...1 Tragedy’s Concerns and Structure………………………………………………………………...4 The Tragedy of Dr. Faustus……………………………………………………………………...13 The Tragedy of Hamlet…………………………………………………………………………..23 The Tragedy of King Lear……………………………………………………………………….34 The Modern Sense of Tragedy…………………………………………………………………...44 Modern Tragedy and Pessimism – Death of a Salesman………………………………………...53 Modern Tragedy and the Absurd – Endgame……………………………………………………63 Conclusion: The Future of Tragedy…………………………………………………………...…70 Introduction: Tragedy and Transcendence Tragedy, in comparison to epic, comedy, satire, and lyric – as representations of life – seems to occupy a more fundamental position. By this I do not mean to say that tragedy is objectively superior to these other genres, but instead that it more earnestly, in some respects, offers insight into human nature, life’s necessities, and the cosmic forces at play in the world as they relate to and have a bearing on human existence.