Stories of the Fallen Willow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sideways Title Page

SIDEWAYS by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor (Based on the novel by Rex Pickett) May 29, 2003 UNDER THE STUDIO LOGO: KNOCKING at a door and distant dog BARKING. NOW UNDER BLACK, A CARD -- SATURDAY The rapping, at first tentative and polite, grows insistent. Then we hear someone getting out of bed. MILES (O.S.) ...the fuck... A door is opened, and the black gives way to blinding white light, the way one experiences the first glimpse of day amid, say, a hangover. A worker, RAUL, is there. MILES (O.S.) Yeah? RAUL Hi, Miles. Can you move your car, please? MILES (O.S.) What for? RAUL The painters got to put the truck in, and you didn’t park too good. MILES (O.S.) (a sigh, then --) Yeah, hold on. He closes the door with a SLAM. EXT. HIDEOUS APARTMENT COMPLEX - DAY SUPERIMPOSE -- SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Wearing only underwear, a bathrobe, and clogs, MILES RAYMOND comes out of his unit and heads toward the street. He passes some SIX MEXICANS, ready to work. 2. He climbs into his twelve-year-old convertible SAAB, parked far from the curb and blocking part of the driveway. The car starts fitfully. As he pulls away, the guys begin backing up the truck. EXT. STREET - DAY Miles rounds the corner and finds a new parking spot. INT. CAR - CONTINUOUS He cuts the engine, exhales a long breath and brings his hands to his head in a gesture of headache pain or just plain anguish. He leans back in his seat, closes his eyes, and soon nods off. -

ALL MY SONS a Play in Three Acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller

ALL MY SONS a play in three acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller (Keller) Kate Keller (Mother) Chris Keller Ann Deever George Deever Dr. Jim Bayliss (Jim) Sue Bayliss Frank Lubey Lydia Lubey Bert Act One The back yard of the Keller home in the outskirts of an American town. August of our era. The stage is hedged on right and left by tall, closely planted poplars which lend the yard a secluded atmosphere. Upstage is filled with the back of the house and its open, unroofed porch which extends into the yard some six feet. The house is two stories high and has seven rooms. It would have cost perhaps fifteen thousand in the early twenties when it was built. Now it is nicely painted, looks tight and comfortable, and the yard is green with sod, here and there plants whose season is gone. At the right, beside the house, the entrance of the driveway can be seen, but the poplars cut off view of its continuation downstage. In the left corner, downstage, stands the four‐foot‐high stump of a slender apple tree whose upper trunk and branches lie toppled beside it, fruit still clinging to its branches. Downstage right is a small, trellised arbor, shaped like a sea shell, with a decorative bulb hanging from its forward‐curving roof. Carden chairs and a table are scattered about. A garbage pail on the ground next to the porch steps, a wire leaf‐burner near it. On the rise: It is early Sunday morning. Joe Keller is sitting in the sun reading the want ads of the Sunday paper, the other sections of which lie neatly on the ground beside him. -

Monthly Invoiced Expenditure Jan

Essex County Fire and Rescue Service January 2017 Purchase Invoice Data INVOICE DOCUMEN DEPARTMENT NOMINAL TYPE OF EXPENDITURE DESCRIPTION PERIOD YEARCODE VALUE ECFRS Ref SUPPLIER DATE T TYPE ICT 2510 IT Communications PAGER RENTAL 28/10/16-27/01/17 10 2017 4180.50 154808 05/10/2016 FPIN PAGEONE COMMUNICATIONS LTD Service Leadership Team 2902 Legal Expenses CANCELLED BY FPIN 157818 10 2017 28476.00 155469 04/11/2016 FPIN ESSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 52.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 26.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 598.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 136.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Property Services 4003 Postage Direct Mailing & Carriage METER RESET 07.11.16 10 2017 25.50 156252 26/11/2016 FPIN PURCHASE POWER - PITNEY BOWES ICT 4005 IT Consumables HP - Low Voltage Power Supply 10 2017 229.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables call out charge to inspect/ser 10 2017 190.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables CREDIT FPIN 156261 10 2017 -95.00 156263 30/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 112.00 156340 02/12/2016 FPIN PHYSIOTHERAPY ESSEX LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 600.00 156340 02/12/2016 -

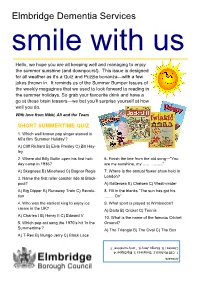

Elmbridge Dementia Services Smile with Us

Elmbridge Dementia Services smile with us Hello, we hope you are all keeping well and managing to enjoy the summer sunshine (and downpours!). This issue is designed for all weather as it’s a Quiz and Puzzle bonanza—with a few jokes thrown in. It reminds us of the Summer Bumper Issues of the weekly magazines that we used to look forward to reading in the summer holidays. So grab your favourite drink and have a go at these brain teasers—we bet you’ll surprise yourself at how well you do. With love from Nikki, Ali and the Team SHORT SUMMERTIME QUIZ 1. Which well known pop singer starred in 60’s film ‘Summer Holiday’? A) Cliff Richard B) Elvis Presley C) Bill Hay- ley 2. Where did Billy Butlin open his first holi- 6. Finish the line from the old song—”You day camp in 1936? are my sunshine, my ….. ……..” A) Skegness B) Minehead C) Bognor Regis 7. Where is the annual flower show held in 3. Name the first roller coaster ride at Black- London? pool? A) Battersea B) Chelsea C) Westminster A) Big Dipper B) Runaway Train C) Revolu- 8. Fill in the blanks “The sun has got his tion ……. On” 4. Who was the earliest king to enjoy ice 9. What sport is played at Wimbledon? cream in the UK? A) Darts B) Cricket C) Tennis A) Charles I B) Henry II C) Edward V 10. What is the name of the famous Cricket 5. Which pop act sang the 1970’s hit ‘In the Ground? Summertime’? A) The Triangle B) The Oval C) The Box A) T-Rex B) Mungo Jerry C) Black Lace ” 7. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

Heads and Tails Unit Overview

6 Heads and tails Unit Overview Outcomes READING In this unit pupils will: Pupils can: ●● Describe wild animals. ●● recognise cognates and deduce meaning of words in ●● Ask and answer about favourite animals. context. ●● Compare different animals’ bodies. ●● understand a poem, find specific information and transfer ●● Write about a wild animal. this to a table. ●● read and complete a gapped text about two animals. Productive Language WRITING VOCABULARY Pupils can: ●● Animals: a crocodile, an elephant, a giraffe, a hippo, ●● write short descriptive texts following a model. a monkey, an ostrich, a pony, a snake. Strategies ●● Body parts: an arm, fingers, a foot, a head, a leg, a mouth, a nose, a tail, teeth, toes, wings. Listen for words that are similar in other languages. L 1 ●● Adjectives: fat, funny, hot, long, short, silly, tall. PB p.35 ex2 PHRASES Before you listen, look at the pictures and guess. ●● It has got/It hasn’t got (a long neck). L 2 AB p.39 ex5 ●● Has it got legs? Yes, it has./No, it hasn’t. Read the questions before you listen. Receptive Language L 3 PB p.39 ex1 VOCABULARY Listen and try to understand the main idea. ●● Animals: butterfly, meerkat, penguin, whale. L 4 ●● Africa, apple, beak, carrot, lake, water, wildlife park. PB p.36 ex1 ●● Eat, live, fly. S Use the model to help you speak. PHRASES 3 PB p.38 ex2 ●● It lives ... Look for words that are similar in other languages. R 2 Recycled Language AB p.38 ex1 VOCABULARY Use your Picture Dictionary to help you spell. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

"So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 3 Article 5 March 2012 Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office Frederick B. Jonassen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Frederick B. Jonassen, Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 853 (2012), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss3/5 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj KISS THE BOOK . YOU’RE PRESIDENT . : “SO HELP ME GOD” AND KISSING THE BOOK IN THE PRESIDENTIAL OATH OF OFFICE Frederick B. Jonassen* INTRODUCTION .................................................854 I. THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE OF “SO HELP ME GOD” AS HISTORICAL PRECEDENT IN THE PRESIDENT’S INAUGURATION ...................859 A. Washington’s “So Help Me God” in the Supreme Court ..........861 B. Newdow v. Roberts.......................................864 II. THE CASE AGAINST “SO HELP ME GOD”..........................870 A. The Washington Irving Recollection ..........................872 B. The Freeman Source ......................................874 C. Two Conjectural Arguments for “So Help Me God” Discredited ...879 D. One More Conjecture .....................................881 III. THE EVIDENCE THAT WASHINGTON KISSED THE BIBLE ..............885 A. First-Hand Accounts of the Biblical Kiss ......................885 B. The Subsequent Tradition ..................................890 1. Andrew Johnson......................................892 2. Ulysses S. Grant......................................892 3. Rutherford B. Hayes...................................893 4. James A. -

The Runners of Shawnee Road

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-20-2013 The Runners of Shawnee Road Melissa Remark University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Remark, Melissa, "The Runners of Shawnee Road" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1761. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1761 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Runners of Shawnee Road A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theater and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Melissa Remark B.A. Trent University, 2010 Diploma, Humber College, 2000 December, 2013 The Sheeny Man rides through the streets pulling his wagon of junk. Sometimes he is black, sometimes he is white, and sometimes he is French. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay