Southern Indian Studies, Vol. 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diffusion of Maize to the Southwestern United States and Its Impact

PERSPECTIVE The diffusion of maize to the southwestern United States and its impact William L. Merrilla, Robert J. Hardb,1, Jonathan B. Mabryc, Gayle J. Fritzd, Karen R. Adamse, John R. Roneyf, and A. C. MacWilliamsg aDepartment of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37102, Washington, DC 20013-7012; bDepartment of Anthropology, One UTSA Circle, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249; cHistoric Preservation Office, City of Tucson, P.O. Box 27210, Tucson, AZ 85726; dDepartment of Anthropology, Campus Box 1114, One Brookings Drive, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130; eCrow Canyon Archaeological Center, 23390 Road K, Cortez, CO 81321; fColinas Cultural Resource Consulting, 6100 North 4th Street, Private Mailbox #300, Albuquerque, NM 87107; and gDepartment of Archaeology, 2500 University Drive Northwest, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Edited by Linda S. Cordell, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, and approved October 30, 2009 (received for review June 22, 2009) Our understanding of the initial period of agriculture in the southwestern United States has been transformed by recent discoveries that establish the presence of maize there by 2100 cal. B.C. (calibrated calendrical years before the Christian era) and document the processes by which it was integrated into local foraging economies. Here we review archaeological, paleoecological, linguistic, and genetic data to evaluate the hypothesis that Proto-Uto-Aztecan (PUA) farmers migrating from a homeland in Mesoamerica intro- duced maize agriculture to the region. We conclude that this hypothesis is untenable and that the available data indicate instead a Great Basin homeland for the PUA, the breakup of this speech community into northern and southern divisions Ϸ6900 cal. -

Machc19-05.4

19th Meeting of the MesoAmerica – Caribbean Sea Hydrographic Commission Regional Capacity Building Update of Brazil on its Regional Project International Hydrographic Organization Organisation Hydrographique Internationale Capacity Building in the Caribbean, South America and Africa - Hydrography Courses Brazil/DHN has been expanding its Capacity Building Project towards other countries in the Amazon region and in the Atlantic Ocean basin. COURSE DESCRIPTION DURATION C-Esp-HN Technician in Hydrography and Navigation (Basic Training) 42 weeks C-Ap-HN Technician in Hydrography and Navigation (IHO Cat. “B”) 35 weeks CAHO Hydrographic Surveyors (IHO Cat. “A”) 50 weeks 2018 – 1 Bolivian Navy Officer (IHO Cat “A”). 2019 – Confirmed: 2 students from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (IHO Cat “A”). Confirmation in progress: Angola (6), Mozambique (4), Bolivia (1), Colombia (1) and Paraguay (1) (IHO Cat “A” and “B”). 2020 – In the near future, Fluminense Federal University (UFF) and other Brazilian universities and governmental institutions in cooperation with DHN will develop a Hydrography Program and a Nautical Cartography Program. International Hydrographic Organization Organisation Hydrographique Internationale 2 Capacity Building - IHO Sponsored Trainings/Courses Work Program Training/Course Date 2018 Maritime Safety Information (MSI) Training Course 16-18 October 18 participants from 12 different countries Argentina (2) Brazil (6) Bolivia (1) Colombia (1) Ecuador (1) El Salvador (1) Guyana (1) Liberia (1) Paraguay (1) Peru (1) Uruguay (1) -

A Glance at Member Countries of the Mesoamerica Integration and Development Project, (LC/MEX/TS.2019/12), Mexico City, 2019

Thank you for your interest in this ECLAC publication ECLAC Publications Please register if you would like to receive information on our editorial products and activities. When you register, you may specify your particular areas of interest and you will gain access to our products in other formats. www.cepal.org/en/publications ublicaciones www.cepal.org/apps Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Mario Cimoli Deputy Executive Secretary Raúl García-Buchaca Deputy Executive Secretary for Administration and Analysis of Programmes Hugo Eduardo Beteta Director ECLAC Subregional Headquarters in Mexico This document was prepared by Leda Peralta Quesada, Associate Economic Affairs Officer, International Trade and Industry Unit, ECLAC Subregional Headquarters in Mexico, under the supervision of Jorge Mario Martínez Piva, and with contributions from Martha Cordero Sánchez, Olaf de Groot, Elsa Gutiérrez, José Manuel Iraheta, Lauren Juskelis, Julie Lennox, Debora Ley, Jaime Olivares, Juan Pérez Gabriel, Diana Ramírez Soto, Manuel Eugenio Rojas Navarrete, Eugenio Torijano Navarro, Víctor Hugo Ventura Ruiz, officials of ECLAC Mexico, as well as Gabriel Pérez and Ricardo Sánchez, officials of ECLAC Santiago. The comments of the Presidential Commissioners-designate and the Executive Directorate of the Mesoamerica Integration and Development Project are gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and may not be those of the Organization. This document is an unofficial translation of an original that did not undergo formal editorial review. The boundaries and names shown on the maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Explanatory notes: - The dot (.) is used to separate the decimals and the comma (,) to separate the thousands in the text. -

1. Presentación. 2.Fundamentación

1 UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES HISTORICO-SOCIALES INTRODUCCION A MESOMERICA Y NUEVOS DESCUBRIMIENTOS PROFR. DR. PEDRO JIMENEZ LARA I.I.H-S 1. Presentación. El presente curso pretende ofrecer una visión de los elementos y períodos culturales que identifican al México Antiguo. Las regiones son: oasisamérica, aridoamérica y mesoamérica Los horizontes que la componen son: arqueolítico, cenolítico inferior, cenolítico superior, protoneolítico, oasisamérica, aridoamérica, mesoamérica y los primeros contactos en el s. XVI: Planteamiento que se hace de esta manera para una mejor comprensión del curso y entender la evolución de los grupos asentados en territorio mexicano. 2.Fundamentación. Las área culturales del México Antiguo no solo se reduce a Mesoamérica como el período de máximo florecimiento que le antecedió a la conquista. En otros tiempos, antes de conocerse esta macroárea cultural, llegaron diversos grupos de cazadores-recolectores nómadas. El proceso evolutivo de estos grupos fue largo y lento, permitiendo avanzar e ir tocando diferentes niveles de desarrollo y los conocimientos necesarios para el cultivo y domesticación de las plantas como uno de los descubrimientos mas importantes durante esta fase que cambio el curso de la historia. Otra de las regiones es la llamada Oasisamérica localizada al sw de E.U. y norte de México, compuesta por grupos sedentarios agrícolas pero con una complejidad similar a la Mesoamericana. El área denominada mesoamérica, espacio donde interactuaron y se desarrollaron diversos grupos culturales, fue la “…sede de la mas alta civilización de la América precolombina. (Niederbeger, 11, 1996), se desarrollo en la mayor parte del territorio mexicano. Mesoamérica, definida así por Kirchhoff en 1943, es punto de referencia no solo para estudiosos del período prehispánico, en el convergen diversos especialistas amparados en diferentes corrientes ideológicas y enfoques: antropólogos, geógrafos prehistoriadores, historiadores, sociólogos, arquitectos, biólogos, sociólogos, por mencionar a algunos. -

Sumpit (Blowgun)

Journal of Education, Teaching and Learning Volume 3 Number 1 March 2018. Page 113-120 p-ISSN: 2477-5924 e-ISSN: 2477-4878 Journal of Education, Teaching, and Learning is licensed under A Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Sumpit (Blowgun) as Traditional Weapons with Dayak High Protection (Study Documentation of Local Wisdom Weak Traditional Weapons of Kalimantan) Hamid Darmadi IKIP PGRI Pontianak, Pontianak, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Dayak ancestors who live amid lush forests with towering tree trees and inhabited by a variety of wild animals and wild animals, inspire for the Dayak's ancestors to make weapons that not only protect themselves from the ferocity of forest life but also have been able to sustain the existence of their survival. Such living conditions have motivated the Dayak ancestors to make weapons called "blowgun" Blowgun as weapons equipped with blowgun called damak. Damak made of bamboo, stick and the like are tapered and given sharp-sharp so that after the target is left in the victim's body. In its use damak smeared with poison. Poison blowgun smeared on the damak where the ingredients used are very dangerous, a little scratched it can cause death. Poison blowgun can be made from a combination of various sap of a particular tree and can also be made from animals. Along with the development of blowgun, era began to be abandoned by Dayak young people. To avoid the typical weapons of this high-end Dayak blowgun from extinction, need to be socialized especially to the young generation and to Dayak young generation especially in order, not to extinction. -

The Americas and Oceania Ben06937.Ch21 538-563.Qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 539

ben06937.Ch21_538-563.qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 538 Worlds Apart: 21 The Americas and Oceania ben06937.Ch21_538-563.qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 539 States and Empires in Mesoamerica States and Empires in South America and North America The Coming of the Incas The Toltecs and the Mexica Inca Society and Religion Mexica Society Mexica Religion The Societies of Oceania Peoples and Societies of the North The Nomadic Foragers of Australia The Development of Pacific Island Societies In November 1519 a small Spanish army entered Tenochtitlan, capital city of the Aztec empire. The Spanish forces came in search of gold, and they had heard many reports about the wealth of the Aztec empire. Yet none of those reports prepared them adequately for what they saw. Years after the conquest of the Aztec empire, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier in the Span- ish army, described Tenochtitlan at its high point. The city itself sat in the water of Lake Tex- coco, connected to the surrounding land by three broad causeways, and as in Venice, canals allowed canoes to navigate to all parts of the city. The imperial palace included many large rooms and apartments. Its armory, well stocked with swords, lances, knives, bows, arrows, slings, armor, and shields, attracted Bernal Díaz’s professional attention. The aviary of Tenochti- tlan included eagles, hawks, parrots, and smaller birds in its collection, and jaguars, mountain lions, wolves, foxes, and rattlesnakes were noteworthy residents of the zoo. To Bernal Díaz the two most impressive sights were the markets and the temples of Te- nochtitlan. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

LA FRONTERA CULTURAL MESO-ARIDOAMERICANA: CONSTRUCCIÓN DE IMAGINARIOS NACIONALISTAS EN LA HISTORIA MEXICANA MESO-ARIDOAMERICAN CULTURAL FRONTIER: CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONALIST IMAGINARIES IN MEXICAN HISTORY Adriana Gómez Aíza PhD en Análisis de Discurso por la Universidad de Essex. Profesora investigadora adscrita al Área Académica de Historia y Antropología, Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. [email protected] Sergio Sánchez Vázquez Doctor en Antropología por la Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Profesor investigador adscrito al Área Académica de Historia y Antropología, Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. [email protected] Nota. Una primera versión de este trabajo se presentó en la Memoria del VI Congreso de la Gran Chichimeca: 1-13. Instituto de Investigaciones Humanísticas, UASLP. México. 2007 Resumen La noción de frontera valida ciertas interpretaciones sobre la historia de una nación: lugar donde se nace y comparte con los demás una identidad, un modo de entenderse a sí mismo en relación con otros, con los que pertenecen a ese entorno y los que son ajenos o viven más allá de los confines que los dividen y separan. Aquí se discute la pertinencia de aplicar el término frontera cultural a la presunta división regional entre grupos sedentarios agrícolas mesoamericanos y grupos chichimecas seminómadas de los desiertos del actual norte de México. Para ello se aborda el papel jugado por Mesoamérica y la Gran Chichimeca en la conformación de imaginarios étnicos y nacionalistas, especialmente el nahua-centrismo impuesto por la conquista española, y la reivindicación del pasado prehispánico como constitutivo de la historia de México, enfatizando el contraste entre la reivindicación oficial del mestizaje a partir de la derrota militar de Tenochtitlán y la exégesis chicana que invoca su pasado en Aztlán, tierra mítica de origen de los mexicanos. -

Reconstructing the History of Mesoamerican Populations Through the Study of the Mitochondrial DNA Control Region

Reconstructing the History of Mesoamerican Populations through the Study of the Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Amaya Gorostiza1,2,Vı´ctor Acunha-Alonzo3,Lucı´a Regalado-Liu1, Sergio Tirado1, Julio Granados4, David Sa´mano5,He´ctor Rangel-Villalobos6, Antonio Gonza´ lez-Martı´n1* 1 Department of Zoology and Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Biology, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2 Laboratorio de Identificacio´n Gene´tica, GENOMICA S.A.U. Grupo Zeltia, Madrid, Spain, 3 Laboratorio de Gene´tica Molecular, Escuela Nacional de Antropologı´a e Historia, Mexico City, Mexico, 4 Divisio´nde Immunogene´tica, Departamento de Trasplantes, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Me´dicas y Nutricio´n Salvador Zubiran, Mexico City, Mexico, 5 Academia de Cultura Cientı´fica – Humanı´stica, Universidad Auto´noma del Estado de Me´xico, Mexico City, Mexico, 6 Instituto de Investigacio´n en Gene´tica Molecular, Centro Universitario de la Cie´naga, Universidad de Guadalajara, Ocotlan, Mexico Abstract The study of genetic information can reveal a reconstruction of human population’s history. We sequenced the entire mtDNA control region (positions 16.024 to 576 following Cambridge Reference Sequence, CRS) of 605 individuals from seven Mesoamerican indigenous groups and one Aridoamerican from the Greater Southwest previously defined, all of them in present Mexico. Samples were collected directly from the indigenous populations, the application of an individual survey made it possible to remove related or with other origins samples. Diversity indices and demographic estimates were calculated. Also AMOVAs were calculated according to different criteria. An MDS plot, based on FST distances, was also built. We carried out the construction of individual networks for the four Amerindian haplogroups detected. -

GLOBAL REGENTS REVIEW PACKET 10 - PAGE 1 of 23

GLOBAL REGENTS REVIEW PACKET 10 - PAGE 1 of 23 THIS IS GLOBAL REGENTS REVIEW PACKET NUMBER TEN THE TOPICS OF STUDY IN THIS PACKET ARE: • MESOAMERICA – THE MAYAS, AZTECS, AND INCAS - This topic is divided into two parts. This packet covers both: 1) Geography’s Impact on Mesoamerica (The Mayas, Aztecs, and Incas) and South America (This topic is also covered in Regents Review Packet Number Two. See GEOGRAPHY IMPACTS HOW PEOPLE DEVELOP, Part 11.) 2) The Mayas, Aztecs, and Incas were highly developed, complex civilizations that used advanced technology. • THE AGE OF EXPLORATION - This topic is divided into seven parts. This packet covers the first two: 1) The Encounter 2) Portugal and Spain: The Search for a Water Route to the Spice Islands of East Asia Global Regents Review Packet #11 covers the last five parts. GLOBAL REGENTS REVIEW PACKET 10 - PAGE 2 of 23 MESOAMERICA - THE MAYAS, AZTECS, AND INCAS (divided into 2 parts) PART 1: Geography’s Impact on Mesoamerica (The Mayas, Aztecs, and Incas) and South America (This topic is also covered in Regents Review Packet Number Two. See GEOGRAPHY IMPACTS HOW PEOPLE DEVELOP, Part 11.) • The Andes Mountains and the Amazon River have influenced South Americaʼs economic and political development. How? These diverse landforms prevented Latin American unity, particularly during the era of the Latin American independence movements in the early 19th century. (The Latin American independence movements will be a topic featured in a future Regents Review Packet.) • A study of Aztec, Maya, and Inca agricultural systems would show that these civilizations adapted to their environments with creative farming techniques Mayas = slash and burn agriculture Aztecs = chinampas (floating gardens) Incas = terrace farming • The Andes Mountains had a great influence on the development of the Inca Empire. -

Chopsticks As a Typical Dayak Borneo Weapon

Chopsticks as a Typical Dayak Borneo Weapon Hamid Darmadi {[email protected]} IKIP PGRI Pontianak Abstract: The ancestors of the Dayak tribe who live amid dense forests and inhabited by various wild animals, inspire and motivate the Dayak tribe to make reliable weapons that are not only able to protect themselves from the fierce forest life, but also able to sustain the existence of the Dayak tribe as a whole . The ferocious wilderness of Borneo island has tapered the determination and enthusiasm "Dayak ancestors make" Typical "weapons called" chopsticks. "Chopsticks are made of iron wood (ironwood). Chopsticks have a length of 1.5 to 2cm. The best size for a chopstick Chopsticks consist of three main parts, namely: Chopsticks, chopsticks (damak) and chopsticks (spear made of selected iron tied to the end of the chopsticks). Chopsticks that rely on this blowing power, has a shooting accuracy of up to 200 meters, effective shooting distance of 25 to 30 meters to "typical" which makes the chopstick gun deadly because at the end of the dam is spiked / smeared poison in the form of gum ipuh and a mixture of deadly animals that are said to have no antidote. with the advent of Technology and Knowledge, chopsticks began to be rarely produced as weapons of war, but more at p production as a sports tool to clot and order. Keywords: Typical Dayak Weapon Chopsticks 1 Introduction 1.1 Background for making Chopsticks Weapons Living amidst a dense forest with tree trees that looms high and is inhabited by various wild and wild animals, has inspired Dayaks to make weapons that are not only able to protect them from the fierce forest life, but also able to sustain their lives both materially and moral. -

State Building in the Americas C. 1200 – C. 1450

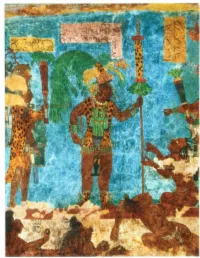

State Building in the Americas c. 1200 – c. 1450 Olmec, Mayan, Aztec, & Inca Empires Mound Building in N. America The Civilizations of America …advanced societies While classical civilizations were developing in were developing in the isolation in the Americas Mediterranean & Asia… During the Neolithic Title Revolution, these nomads settled into ■ Text farming villages; Some of which became advanced civilizations During the Ice Age, prehistoric nomads migrated across the land bridge between Asia & America The Olmecs The Olmecs are often called the “mother culture” because they influenced other Mesoamerican societies The first American civilization were people known as the Olmec in an area known as Mesoamerica The Olmecs developed a strong trade network in MesoamericaThe Olmecs that brought them great wealth The Olmecs used their Olmec trade allowed wealth to build large stone them to spread their monuments & pyramids to culture to other honor their leaders & gods Mesoamericans For unknown reasons, the Olmec civilization declined by 400 B.C. but their cities & symbols influenced later cultures, especially the Mayans Government: Mayans While theEconomy Olmecs: were in were divided intoThe MayansdeclineThe Mayan around economy 400 B.C., individual city-states thewas Mayans based were on trade evolving & & ruled by king-gods borrowedfarming many maize, Olmec beans ideas Society: (1) Kings (dynasties) The Mayans (2) Nobles, priests (3) warriors (4) Merchants, artisans (5) Peasants The Mayans Religion: Mayans were polytheistic & offered their blood, food, & sometimes human sacrifices to please the gods Technology: Mayans invented a writing based on pictures called glyphs, an accurate 365-day calendar, & advanced temples Tikal Chichen Itza The shadow of a serpent appears on one side of the pyramid stairs only on the equinox. -

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields.