The Hall of Mexico and Central America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Early Mesoamerican Civilizations

2 Early Mesoamerican Civilizations MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES CULTURAL INTERACTION The Later American civilizations • Mesoamerica • Zapotec Olmec created the Americas’ relied on the technology and • Olmec • Monte first civilization, which in turn achievements of earlier cultures Albán influenced later civilizations. to make advances. SETTING THE STAGE The story of developed civilizations in the Americas begins in a region called Mesoamerica. (See map on opposite page.) This area stretches south from central Mexico to northern Honduras. It was here, more than 3,000 years ago, that the first complex societies in the Americas arose. TAKING NOTES The Olmec Comparing Use a Mesoamerica’s first known civilization builders were a people known as the Venn diagram to compare Olmec and Olmec. They began carving out a society around 1200 B.C. in the jungles of south- Zapotec cultures. ern Mexico. The Olmec influenced neighboring groups, as well as the later civi- lizations of the region. They often are called Mesoamerica’s “mother culture.” The Rise of Olmec Civilization Around 1860, a worker clearing a field in the Olmec hot coastal plain of southeastern Mexico uncovered an extraordinary stone sculp- both ture. It stood five feet tall and weighed an estimated eight tons. The sculpture Zapotec was of an enormous head, wearing a headpiece. (See History Through Art, pages 244–245.) The head was carved in a strikingly realistic style, with thick lips, a flat nose, and large oval eyes. Archaeologists had never seen anything like it in the Americas. This head, along with others that were discovered later, was a remnant of the Olmec civilization. -

The Diffusion of Maize to the Southwestern United States and Its Impact

PERSPECTIVE The diffusion of maize to the southwestern United States and its impact William L. Merrilla, Robert J. Hardb,1, Jonathan B. Mabryc, Gayle J. Fritzd, Karen R. Adamse, John R. Roneyf, and A. C. MacWilliamsg aDepartment of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37102, Washington, DC 20013-7012; bDepartment of Anthropology, One UTSA Circle, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249; cHistoric Preservation Office, City of Tucson, P.O. Box 27210, Tucson, AZ 85726; dDepartment of Anthropology, Campus Box 1114, One Brookings Drive, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130; eCrow Canyon Archaeological Center, 23390 Road K, Cortez, CO 81321; fColinas Cultural Resource Consulting, 6100 North 4th Street, Private Mailbox #300, Albuquerque, NM 87107; and gDepartment of Archaeology, 2500 University Drive Northwest, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Edited by Linda S. Cordell, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, and approved October 30, 2009 (received for review June 22, 2009) Our understanding of the initial period of agriculture in the southwestern United States has been transformed by recent discoveries that establish the presence of maize there by 2100 cal. B.C. (calibrated calendrical years before the Christian era) and document the processes by which it was integrated into local foraging economies. Here we review archaeological, paleoecological, linguistic, and genetic data to evaluate the hypothesis that Proto-Uto-Aztecan (PUA) farmers migrating from a homeland in Mesoamerica intro- duced maize agriculture to the region. We conclude that this hypothesis is untenable and that the available data indicate instead a Great Basin homeland for the PUA, the breakup of this speech community into northern and southern divisions Ϸ6900 cal. -

U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: an Overview

Updated February 16, 2021 U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: An Overview Introduction for Engagement in Central America and, with congressional Central America has received considerable attention from support, more than doubled annual foreign aid to the region. U.S. policymakers over the past decade, as it has become a major transit corridor for illicit narcotics and a top source of The Trump Administration repeatedly sought to scale back irregular migration to the United States. In FY2019, U.S. funding for the Central America strategy. It proposed authorities at the southwest border apprehended nearly significant year-on-year assistance cuts for the region in 608,000 unauthorized migrants from El Salvador, each of its annual budget requests and suspended most aid Guatemala, and Honduras (the Northern Triangle of Central for the Northern Triangle in March 2019, two years into the America); 81% of those apprehended were families or strategy’s on-the-ground implementation. Congress chose unaccompanied minors, many of whom were seeking not to adopt many of the proposed cuts, but annual funding asylum (see Figure 1). Although the Coronavirus Disease for the Central America strategy declined from $750 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic disrupted illicit trafficking and million in FY2017 to $505.9 million in FY2021—a nearly irregular migration flows in FY2020, many analysts expect 33% drop over four years (see Figure 2). a resurgence once governments throughout the Western Hemisphere begin lifting border restrictions. Both Congress and the Biden Administration have called for a reexamination of U.S. policy toward Central America Figure 1. U.S. -

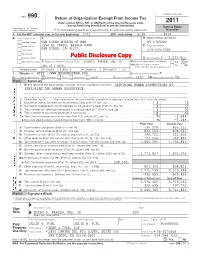

990 Informational Returns, Year Ending June 30, 2012

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code 2011 (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 7/01 , 2011, and ending 6/30 , 2012 B Check if applicable: C D Employer Identification Number Address change SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF MAN 95-1709290 Name change 1350 EL PRADO, BALBOA PARK E Telephone number SAN DIEGO, CA 92101 Initial return 619-239-2001 Terminated Amended return PublicDisclosureCopy G Gross receipts $ 2,021,845. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MICAH D. PARZEN, PHD, JD H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? YesX No H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No SAME AS C ABOVE If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt statusX 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G HTTP://WWW.MUSEUMOFMAN.ORG H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization:X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of Formation: 1915 M State of legal domicile: CA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: INSPIRING HUMAN CONNECTIONS BY EXPLORING THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE. 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Pre-Columbian Agriculture in Mexico Carol J

Pre-Columbian Agriculture in Mexico Carol J. Lange, SCSC 621, International Agricultural Research Centers- Mexico, Study Abroad, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Texas A&M University Introduction The term pre-Columbian refers to the cultures of the Americas in the time before significant European influence. While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus, in practice the term usually includes indigenous cultures as they continued to develop until they were conquered or significantly influenced by Europeans, even if this happened decades or even centuries after Columbus first landed in 1492. Pre-Columbian is used especially often in discussions of the great indigenous civilizations of the Americas, such as those of Mesoamerica. Pre-Columbian civilizations independently established during this era are characterized by hallmarks which included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Many of these civilizations had long ceased to function by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late fifteenth-early sixteenth centuries), and are known only through archaeological evidence. Others were contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Maya, had their own written records. However, most Europeans of the time largely viewed such text as heretical and few survived Christian pyres. Only a few hidden documents remain today, leaving us a mere glimpse of ancient culture and knowledge. Agricultural Development Early inhabitants of the Americas developed agriculture, breeding maize (corn) from ears 2-5 cm in length to perhaps 10-15 cm in length. Potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, and avocados were among other plants grown by natives. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tv1p1rr Author Flores-Marcial, Xochitl Marina Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 © Copyright by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kevin B. Terraciano, Chair My project traces the evolution of the Zapotec cultural practice of guelaguetza, an indigenous sharing system of collaboration and exchange in Mexico, from pre-Columbian and colonial times to the present. Ironically, the term "guelaguetza" was appropriated by the Mexican government in the twentieth century to promote an annual dance festival in the city of Oaxaca that has little to do with the actual meaning of the indigenous tradition. My analysis of Zapotec-language alphabetic sources from the Central Valley of Oaxaca, written from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, reveals that Zapotecs actively participated in the sharing system during this long period of transformation. My project demonstrates that the Zapotec sharing economy functioned to build and reinforce social networks among households in Zapotec communities. -

Regional Fact Sheet – North and Central America

SIXTH ASSESSMENT REPORT Working Group I – The Physical Science Basis Regional fact sheet – North and Central America Common regional changes • North and Central America (and the Caribbean) are projected to experience climate changes across all regions, with some common changes and others showing distinctive regional patterns that lead to unique combinations of adaptation and risk-management challenges. These shifts in North and Central American climate become more prominent with increasing greenhouse gas emissions and higher global warming levels. • Temperate change (mean and extremes) in observations in most regions is larger than the global mean and is attributed to human influence. Under all future scenarios and global warming levels, temperatures and extreme high temperatures are expected to continue to increase (virtually certain) with larger warming in northern subregions. • Relative sea level rise is projected to increase along most coasts (high confidence), and are associated with increased coastal flooding and erosion (also in observations). Exceptions include regions with strong coastal land uplift along the south coast of Alaska and Hudson Bay. • Ocean acidification (along coasts) and marine heatwaves (intensity and duration) are projected to increase (virtually certain and high confidence, respectively). • Strong declines in glaciers, permafrost, snow cover are observed and will continue in a warming world (high confidence), with the exception of snow in northern Arctic (see overleaf). • Tropical cyclones (with higher precipitation), severe storms, and dust storms are expected to become more extreme (Caribbean, US Gulf Coast, East Coast, Northern and Southern Central America) (medium confidence). Projected changes in seasonal (Dec–Feb, DJF, and Jun–Aug, JJA) mean temperature and precipitation at 1.5°C, 2°C, and 4°C (in rows) global warming relative to 1850–1900. -

Machc19-05.4

19th Meeting of the MesoAmerica – Caribbean Sea Hydrographic Commission Regional Capacity Building Update of Brazil on its Regional Project International Hydrographic Organization Organisation Hydrographique Internationale Capacity Building in the Caribbean, South America and Africa - Hydrography Courses Brazil/DHN has been expanding its Capacity Building Project towards other countries in the Amazon region and in the Atlantic Ocean basin. COURSE DESCRIPTION DURATION C-Esp-HN Technician in Hydrography and Navigation (Basic Training) 42 weeks C-Ap-HN Technician in Hydrography and Navigation (IHO Cat. “B”) 35 weeks CAHO Hydrographic Surveyors (IHO Cat. “A”) 50 weeks 2018 – 1 Bolivian Navy Officer (IHO Cat “A”). 2019 – Confirmed: 2 students from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (IHO Cat “A”). Confirmation in progress: Angola (6), Mozambique (4), Bolivia (1), Colombia (1) and Paraguay (1) (IHO Cat “A” and “B”). 2020 – In the near future, Fluminense Federal University (UFF) and other Brazilian universities and governmental institutions in cooperation with DHN will develop a Hydrography Program and a Nautical Cartography Program. International Hydrographic Organization Organisation Hydrographique Internationale 2 Capacity Building - IHO Sponsored Trainings/Courses Work Program Training/Course Date 2018 Maritime Safety Information (MSI) Training Course 16-18 October 18 participants from 12 different countries Argentina (2) Brazil (6) Bolivia (1) Colombia (1) Ecuador (1) El Salvador (1) Guyana (1) Liberia (1) Paraguay (1) Peru (1) Uruguay (1) -

We the American...Hispanics

WE-2R e the American... Hispanics Issued September 1993 U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration BUREAU OF THE CENSUS Acknowledgments This report was prepared by staff of the Ethnic and Hispanic Statistics Branch under the supervisionJorge ofdel Pinal. General direction was providedSusan by J. Lapham, Population Division. The contents of the report were reviewed byJanice Valdisera andMichael Levin, Population Division, and Paula Coupe andDwight Johnson, Public Information Office. Marie Pees, Population Division, provided computer programming support. Debra Niner andMary Kennedy, Population Division, provided review assistance. Alfredo Navarro, Decennial Statistical Studies Division provided sampling review. The staff of Administrative and Publications Services Division, Walter C. Odom, Chief, performed publication planning, design, composition, editorial review, and printing planning and procurement.Cynthia G. Brooks provided publication coordination and editing.Theodora Forgione provided table design and composition services.Kim Blackwell provided design and graphics services.Diane Oliff–Michael coordinated printing services. e, the American Hispanics Introduction We, the American Hispanics traceWe have not always appeared in the our origin or descent to Spaincensus or to as a separate ethnic group. Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and In 1930, Mexicans" were counted many other SpanishĆspeaking counĆand in 1940, persons of Spanish tries of Latin America. Our ancesĆmother tongue" were reported. In tors were among the early explorers1950 and 1960, persons of Spanish and settlers of the New World.surname" In were reported. The 1970 1609, 11 years before the Pilgrimscensus asked persons about their landed at Plymouth Rock, our MestiĆorigin," and respondents could zo (Indian and Spanish) ancestorschoose among several Hispanic oriĆ settled in what is now Santa Fe,gins listed on the questionnaire. -

A Glance at Member Countries of the Mesoamerica Integration and Development Project, (LC/MEX/TS.2019/12), Mexico City, 2019

Thank you for your interest in this ECLAC publication ECLAC Publications Please register if you would like to receive information on our editorial products and activities. When you register, you may specify your particular areas of interest and you will gain access to our products in other formats. www.cepal.org/en/publications ublicaciones www.cepal.org/apps Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Mario Cimoli Deputy Executive Secretary Raúl García-Buchaca Deputy Executive Secretary for Administration and Analysis of Programmes Hugo Eduardo Beteta Director ECLAC Subregional Headquarters in Mexico This document was prepared by Leda Peralta Quesada, Associate Economic Affairs Officer, International Trade and Industry Unit, ECLAC Subregional Headquarters in Mexico, under the supervision of Jorge Mario Martínez Piva, and with contributions from Martha Cordero Sánchez, Olaf de Groot, Elsa Gutiérrez, José Manuel Iraheta, Lauren Juskelis, Julie Lennox, Debora Ley, Jaime Olivares, Juan Pérez Gabriel, Diana Ramírez Soto, Manuel Eugenio Rojas Navarrete, Eugenio Torijano Navarro, Víctor Hugo Ventura Ruiz, officials of ECLAC Mexico, as well as Gabriel Pérez and Ricardo Sánchez, officials of ECLAC Santiago. The comments of the Presidential Commissioners-designate and the Executive Directorate of the Mesoamerica Integration and Development Project are gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and may not be those of the Organization. This document is an unofficial translation of an original that did not undergo formal editorial review. The boundaries and names shown on the maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Explanatory notes: - The dot (.) is used to separate the decimals and the comma (,) to separate the thousands in the text.