Bhavachakra and Mindfulness 291119

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of Beef Producton Nirvana

Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Nirvana: What does that mean? In Search of Beef Produc0on Nirvana • In the Buddhist tradi5on, nirvana is described as the ex5nguishing of the fires that cause suffering and rebirth.[29] These fires are typically iden5fied as the fires of aachment (raga), aversion (dvesha) and ignorance (moha or avidya). • In Hindu philosophy, it is the union with Brahman, the divine ground of existence, and the experience of blissful Things a cow-calf producer learns when you egolessness.[8] own a feedyard: what drives profit? Challenges we face: Rex Ranch • Weather volality •Price volality • Trust between segments • Adding real value to our produc5on • Answers come excruciangly slow (Environment or Genec?) • 2 year concep5on to harvest Excel Beef •7 year gene5c interval Deseret Cattle • Applying research findings correctly in various systems Feeders Weather Volality Table 3. Rex Ranch Annual Calf Cost ($/head) The following events are based on a 201 Average true story. 1 2012 2013 2014 2015 Variao Calf Cost 453 635 876 591 579 n Variaon from previous year (20) 182 241 (285) (12) 148 BIF 2016 General Session II 1 Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Trust between Price Volality segments • Weighing condi5ons • Do what is best for the cale instead of worry • Streamline vaccinaon about who gets the Table 2. Percentage variaon in revenue per head from one year protocol advantage. to the next • Sharing in added value ??? 201 201 201 201 5 year Avg. $/ 2 3 4 5 2016 avg.d head e Jan-Mar 550 lb. Steer a 16% -2% 26% 28% -30% 20% $ -

The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 22, 2015 The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo University of Hamburg Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo1 Abstract With this paper I examine the narrative that in the Cullavagga of the Theravāda Vinaya forms the background to the different rules on bhikkhunī ordination, alternating between translations of the respective portions from the original Pāli and discussions of their implications. An appendix to the paper briefly discusses the term paṇḍaka. Introduction In what follows I continue exploring the legal situation of bhikkhunī or- dination, a topic already broached in two previous publications. In “The Legality of Bhikkhunī Ordination” I concentrated in particular on the legal dimension of the ordinations carried out in Bodhgayā in 1998.2 Based on an appreciation of basic Theravāda legal principles, I discussed the nature of the garudhammas and the need for a probationary training 1 Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, University of Hamburg, and Dharma Drum Insti- tute of Liberal Arts, Taiwan. I am indebted to bhikkhu Ariyadhammika, bhikkhu Bodhi, bhikkhu Brahmāli, bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā, and Petra Kieffer-Pülz for commenting on a draft version of this article. 2 Anālayo (“The Legality”). Anālayo, The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination 402 as a sikkhamānā, showing that this is preferable but not indispensable for a successful bhikkhunī ordination. -

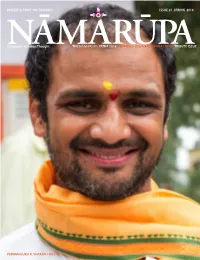

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

RODDY-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Conor Roddy 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Conor Roddy Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Nietzsche’s Buddhist Leidmotive: A Comparative Study of Nietzsche’s Response to the Problem of Suffering Committee: Kathleen Marie Higgins, Supervisor Katherine Arens Lars Gustafsson A. P. Martinich Stephen H. Phillips Nietzsche’s Buddhist Leidmotive: A Comparative Study of Nietzsche’s Response to the Problem of Suffering by Conor Roddy, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2011 Dedication In loving memory of my parents Larry and Patricia Roddy Acknowledgements ―For Confucius,‖ as Herbert Fingarette once remarked, ―unless there are at least two human beings, there can be no human beings‖ (217). One cannot become a person on one‘s own in other words, and although it sometimes seems like a lonely process, one cannot write a dissertation by oneself either. There are so many people who made so many things possible for me to whom I wish to express my gratitude, and since I‘m not planning on writing another dissertation in the near future, I‘m going to do so now. I want to thank all my professors in Dublin, Honolulu, and Austin. When I was an undergraduate in Ireland, it was a passing remark by William Lyons that first got me interested in Nietzsche. During my time in Hawaii, Arindam Chakrabarti, Graham Parkes, and Roger Ames were particularly helpful. -

FPMT Retreat Prayer Book Changes

FPMT Retreat Prayer Book Changes 8/15/2009 After the 100 Million Mani Retreat at Institut Vajra Yogini in France, Education Services received a list of corrections to the FPMT Retreat Prayer Book. These changes are listed below, with the corresponding text included for each change. You may simply mark the changes in your existing copy with a pen, or may print these pages and cut out the corresponding sections and tape them over the mistaken passages in your prayer book. Retreat Prayer Books purchased from Kadampa Center for the Light of the Path retreat already include these changes and do not need to be corrected. For those who may be daunted by adjusting your current copy, new copies may be purchased from Kadampa Center. PAGE 17 Remove the title Inner Mandala Offering. According to Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s teachings, this is not an inner mandala offering. There is no replacement title for this prayer. PAGE 29 Replace the subtitle Visualization with the subtitle: How to Meditate Before the Practice PAGE 31 After the end of the first full paragraph, add the subtitle (the paragraph under the new title has not changed, but is included here for convenience): How to Meditate During the Practice Think that each one of these buddhas is the embodiment of all three times ten directions Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, and all statues, stupas, and scriptures. Think they embody all holy objects, whose essence is the Guru. Have complete faith that each one has the power to purify all your negative karmas and imprints, accumulated since beginningless time. -

In the Works of J.M.G. Le Clézio: Their Force, Their Limitations, and Their Relationship to Alterity

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2007 The Complex Ambivalence of ‘Privileged Moments’ in the Works of J.M.G. Le Clézio: Their Force, Their Limitations, and Their Relationship to Alterity Keith Aaron Moser University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the French Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Moser, Keith Aaron, "The Complex Ambivalence of ‘Privileged Moments’ in the Works of J.M.G. Le Clézio: Their Force, Their Limitations, and Their Relationship to Alterity. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/248 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Keith Aaron Moser entitled "The Complex Ambivalence of ‘Privileged Moments’ in the Works of J.M.G. Le Clézio: Their Force, Their Limitations, and Their Relationship to Alterity." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Karen Levy, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: John Romeiser, Stefanie Ohnesorg, Lisi Schoenbach Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2006 Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Capriles, E. (2006). Capriles, E. (2006). Beyond mind II: Further steps to a metatranspersonal philosophy and psychology. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25(1), 1–44.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25 (1). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.24972/ijts.2006.25.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of The Andes Mérida, Venezuela Some of Wilber’s “holoarchies” are gradations of being, which he views as truth itself; however, being is delusion, and its gradations are gradations of delusion. Wilber’s supposedly universal ontogenetic holoarchy contradicts all Buddhist Paths, whereas his view of phylogeny contradicts Buddhist Tantra and Dzogchen, which claim delusion/being increase throughout the aeon to finally achieve reductio ad absur- dum. Wilber presents spiritual healing as ascent; Grof and Washburn represent it as descent—yet they are all equally off the mark. -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust.