Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ctffta Ignaljjre of Certifying Official/Title ' Daw (

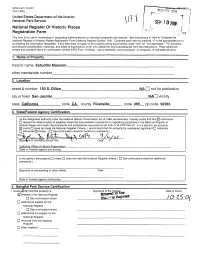

NFS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register Of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Estudillo Mansion_____________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 150 S. Dillon________________ NA CH not for publication city or town San Jacinto____________________ ___NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Riverside. code 065_ zip code 92583 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this 12 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

Journal of Sd History

T HE J OURNAL OF SANDIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/ SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY MCCLAIN Editors COLIN R. FISHER DAWN M. RIGGS Review Editors MATTHEW BOKOVOY Contributing Editor Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 81825, San Diego, California 92138 ISSN 0022-4383 T HE J OURNAL OF SAN DIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the MATTHEW BOKOVOY San Diego Historical Society at University of Oklahoma 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 DONALD C. CUTTER Albuquerque, New Mexico A $50.00 annual membership in the San WILLIAM DEVERELL Diego Historical Society includes subscrip- University of Southern California; Director, Huntington-USC Institute on California tion to The Journal of San Diego History and and the West the SDHS Times. Back issues and microfilm copies are available. VICTOR GERACI University of California, Berkeley Articles and book reviews for publication PHOEBE KROPP consideration, as well as editorial correspon- University of Pennsylvania dence should be addressed to the ROGER W. LOTCHIN Editors, The Journal of San Diego History University of North Carolina Department of History, University of San at Chapel Hill Diego, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA NEIL MORGAN 92110 Journalist DOYCE B. NUNIS, JR. All article submittals should be typed and University of Southern California double spaced, and follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors should submit four JOHN PUTMAN San Diego State University copies of their manuscript, plus an electronic copy, in MS Word or in rich text format ANDREW ROLLE (RTF). -

Journal of San Diego History V 50, No 1&2

T HE J OURNAL OF SANDIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/ SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY MCCLAIN Editors COLIN FISHER DAWN M. RIGGS Review Editors MATTHEW BOKOVOY Contributing Editor Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 81825, San Diego, California 92138 ISSN 0022-4383 T HE J OURNAL OF SAN DIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the MATTHEW BOKOVOY San Diego Historical Society at University of Oklahoma 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 DONALD C. CUTTER Albuquerque, New Mexico A $50.00 annual membership in the San WILLIAM DEVERELL Diego Historical Society includes subscrip- University of Southern California; Director, Huntington-USC Institute on California tion to The Journal of San Diego History and and the West the SDHS Times. Back issues and microfilm copies are available. VICTOR GERACI University of California, Berkeley Articles and book reviews for publication PHOEBE KROPP consideration, as well as editorial correspon- University of Pennsylvania dence should be addressed to the ROGER W. LOTCHIN Editors, The Journal of San Diego History University of North Carolina Department of History, University of San at Chapel Hill Diego, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA NEIL MORGAN 92110 Journalist DOYCE B. NUNIS, JR. All article submittals should be typed and University of Southern California double spaced, and follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors should submit four JOHN PUTMAN San Diego State University copies of their manuscript, plus an electronic copy, in MS Word or in rich text format ANDREW ROLLE (RTF). -

Cultural Resources Assessment

CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT RANCHO DIAMANTE PROJECT CITY OF HEMET RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA December 2019 CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT RANCHO DIAMANTE PROJECT CITY OF HEMET RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: City of Hemet H.P. Kang Associate Planner 445 E. Florida Avenue Hemet, California 92543 Prepared by: Riordan Goodwin, Archaeologist LSA Associates, Inc. 1500 Iowa Avenue Riverside, California 92507 (951) 781‐9310 LSA Project No. HET1601 National Archaeological Database Information (NADB): Type of Study: Reconnaissance Survey Sites Recorded: 33‐015743/CA‐RIV‐8196, 33‐015900/CA‐RIV‐15900 (updates); LSA‐HET1601‐S‐1 USGS 7.5′ Quadrangle: Winchester, California Acreage: ~258.7 acres Key Words: Hemet, Phase I Survey, positive results, historic period resources December 2019 C ULTURAL R ESOURCES A SSESSMENT R ANCHO D IAMANTE P ROJECT D ECEMBER 2019 C ITY OF H EMET, C ALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The City of Hemet retained LSA Associates, Inc. to conduct a cultural resources assessment for the proposed construction of the Rancho Diamante Project in the City of Hemet, in Riverside County, California. This cultural resources assessment was completed pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The cultural resources assessment included records searches, additional research, and field surveys of the project area. Three previously documented cultural resources were identified within the project area: a still‐active subsurface aqueduct (33‐015734), an abandoned railroad line (33‐ 015743), and the former site of an early 20th century farm (33‐015900). One additional linear resource that transects the project area (Hemet Channel) was also documented. Although previously evaluated as not significant under CEQA, the farm site retains some potential for subsurface deposits. -

Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, Circa 1852-1904

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb109nb422 Online items available Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Finding Aid written by Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Documents BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM 1 Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in Cali... Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt. Date Completed: March 2008 © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Documents pertaining to the adjudication of private land claims in California Date (inclusive): circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892 Microfilm: BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM Creators : United States. District Court (California) Extent: Number of containers: 857 Cases. 876 Portfolios. 6 volumes (linear feet: Approximately 75)Microfilm: 200 reels10 digital objects (1494 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: In 1851 the U.S. -

Phase I Environmental Site Assessment West Residential Area

PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL SITE ASSESSMENT Otay Ranch Village 13 - West Residential Area Parcels A and B North of Otay Lakes Road Chula Vista, California 91914 C2C Project Number: 2009-082 Prepared for: The Otay Ranch Company 1392 East Palomar Street, Suite 202 Chula Vista, California 91913 Prepared by: Coast 2 Coast Environmental, Inc. 13964 Boquita Drive Del Mar, California 92014 (619) 889-6232 [email protected] September 11, 2009 Revised November 5, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... iii 2.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 2.1 Purpose.............................................................................................................................1 2.2 Scope of Services.............................................................................................................1 2.3 Significant Assumptions and Data Gaps .........................................................................2 2.4 Limitations .......................................................................................................................2 2.5 Exceptions to ASTM Standard Practice E1527-05..........................................................2 2.6 Special Terms and Conditions .........................................................................................2 2.7 User Reliance...................................................................................................................2 -

Phase 1 Cultural Resources Assessment: Core5 Rider Commerce Center Project, City of Perris, Riverside County, California

PHASE 1 CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT: CORE5 RIDER COMMERCE CENTER PROJECT, CITY OF PERRIS, RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EPD Solutions, Inc. 2 Park Plaza, Ste. 1120 Irvine, CA 92614 Prepared on Behalf of: Core5 Industrial Partners 300 Spectrum Center Drive Suite 880 Irvine, CA 92618 Prepared by: Matthew Wetherbee, MSc., RPA Principal Investigator: Tria Belcourt, M.A., RPA, Riverside County Qualified Archaeologist Material Culture Consulting, Inc 2701-B North Towne Avenue Pomona, CA 91767 626-205-8279 October 2020 *REVISED April 2021 Type of Study: Cultural resources assessment Cultural Resources within Area of Potential Impact: None USGS 7.5-minute Quadrangle: Perris, Section 17 of Township 4S, Range 3W APN(s): 300-210-029, 300-210-011, 300-210-012, and 300-210-013 Survey Area: Approx. 11.2 acres Date of Fieldwork: August 20, 2020 and March 30, 2021 Key Words: Archaeology, CEQA, Phase I Survey, Negative Cultural Result, Riverside County MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Core5 Industrial Partners proposes the construction of a new commercial complex, called the Core5 Rider Commerce Center (Project). The proposed Project consists of development of a high cube industrial building on an approximately 11.2-acre site (APN 300-210-029, 300-210-011, 300-210-012, and 300-210-013), located at the southwest corner of East Rider Street and Wilson Avenue, within the Perris Valley Commerce Center Specific Plan, City of Perris, Riverside County, California. Material Culture Consulting, Inc. (MCC) was retained by E|P|D Solutions, Inc. to conduct a Phase I cultural resource investigation of the Project Area. These assessments were conducted in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), and included cultural records searches, a search of the Sacred Lands File (SLF) by the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC), outreach efforts with 21 Native American tribal representatives, background research, and a pedestrian field survey. -

APPENDIX G ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES EVALUATION to the DRAFT SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT

OTAY CROSSINGS COMMERCE PARK APPENDIX G ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES EVALUATION to the DRAFT SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT EIR 93-19-006Q, TM 5405RPL7 SCH NO. 2006041039 Lead Agency: County of San Diego Department of Planning and Land Use 5201 Ruffin Road, Suite B San Diego, California 92123 Contact: Robert Hingtgen (858) 694-3712 MAY 2010 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES EVALUATION, OTAY CROSSINGS COMMERCE PARK, OTAY MESA, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA TM 5405RPL7 Submitted to: County of San Diego Department of Planning and Land Use 5201 Ruffin Road, Suite B San Diego, California 92123-1666 (858) 694-2960 Prepared for: Kearny PCCP Otay 311, LLC 655 West Broadway, Suite 1600 San Diego, California 92101 Prepared by: Affinis Shadow Valley Center 847 Jamacha Road El Cajon, California 92019 (619) 441-0144 Mary Robbins-Wade, M.A. (R.P.A.) Director of Cultural Resources August 2005 Revised August 2006 Revised November 2006 Revised September 2007 Revised August 2008 Revised September 2009 Revised April 2010 Affinis Job No. 2232/1966 USGS quadrangle: Otay M esa (7.5' series) Acreage: approx. 311 acres Keywords: Archaeological evaluation; Otay Mesa, San Diego County; prehistoric and historic sites; sparse lithic scatters; historic debris, homestead sites; CA-SDI-8076/CA-SDI-8079, CA-SDI-8078, CA-SDI-8080, CA-SDI-8081, CA-SDI-10,299, CA-SDI-11,793, CA-SDI- 11,794, CA-SDI-11,798, CA-SDI-11,799H, CA-SDI-11,800, CA-SDI-11,801, CA-SDI-11,802H, CA-SDI-12,888H, CA-SDI-15,872, CA-SDI- 15,873, CA-SDI-15,875; T18S, R1W, Sections 31 and 32 NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA BASE INFORMATION Authors: Mary Robbins-Wade Consulting firm: Affinis, 847 Jamacha Road, El Cajon, California 92019 (619) 441-0144 Report Date: August 2005, Revised August 2006, Revised November 2006, Revised September 2007, Revised August 2008, Revised September 2009, Revised April 2010 Report Title: Archaeological Resources Evaluation, Otay Crossings Commerce Park, Otay Mesa, San Diego County, California. -

A PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCE INVESTIGATION for the PERRIS TRUCK TERMINAL PROJECT on MARKHAM STREET, PERRIS, RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA (Apns 302-110-031 and -032)

A PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCE INVESTIGATION FOR THE PERRIS TRUCK TERMINAL PROJECT ON MARKHAM STREET, PERRIS, RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA (APNs 302-110-031 and -032) Prepared for: LILBURN CORPORATION Attn: Cheryl Tubbs 1905 Business Center Drive San Bernardino, California 92408 Prepared by: McKENNA et al. 6008 Friends Avenue Whittier, California 90601-3724 (562) 696-3852 [email protected] Author and Principal Investigator: Jeanette A. McKenna, MA/RPA/HonDL Job No. 02-20-04-2064 April 24, 2020 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATABASE SUMMARY Author(s): Jeanette A. McKenna Consulting Firm: McKenna et al. 6008 Friends Avenue Whittier, California 90601-3724 (562) 696-3852 (Office) (562) 754-7712 (Cell) Report Date: April 24, 2020 Report Title: A Phase I Cultural Resource Investigation for the Perris Truck Terminal Project on Markham Street, Perris, Riverside County, California Prepared for: Lilburn Corporation Attn: Cheryl Tubbs 1905 Business Center Drive San Bernardino, California 92408 Submitted to: Lilburn Corporation Attn: Cheryl Tubbs 1905 Business Center Drive San Bernardino, California 92408 Submitted by: McKenna et al. 6008 Friends Avenue Whittier, California 90601-3724 APNs: 302-110-031 and 302-110-032 USGS Quad: Perris (7.5’; 1:64,000) Study Area: 9.54 acres (Riverside Tract, Block 6, Lot 6); North side of Markham Street; east of Perris Blvd.; Township 4 South; Range 3 West; SW ¼ of NW ¼ of Section 5. Key Words: Perris; Perris Valley; Kellogg Property; Ashley Property; Riverside Tract, Block 6; Agriculture; Phase I archaeological survey; CA-RIV-8312; Primary Record 33-016078. i MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This Phase I cultural resource investigation for the Perris Truck Terminal Project was initiated by McKenna et al. -

A Phase I Cultural Resources Survey for the Idi Indian Avenue and Ramona Expressway Project

A PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY FOR THE IDI INDIAN AVENUE AND RAMONA EXPRESSWAY PROJECT PERRIS, CALIFORNIA APNs 302-060-002, -005, -006, and -038, 302-050-034 and -036 Submitted to: City of Perris Planning and Development 135 North D Street Perris, California 92570 Prepared for: Steve Hollis IDI Ramona, LLC 8 Corporate Park, Suite 300 Irvine, California 92606 Prepared by: Andrew J. Garrison and Brian F. Smith Brian F. Smith and Associates, Inc. 14010 Poway Road, Suite A Poway, California 92064 August 23, 2018; Revised February 7, 2019 A Phase I Cultural Resources Survey for the IDI Project __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Archaeological Database Information Authors: Andrew J. Garrison and Brian F. Smith Consulting Firm: Brian F. Smith and Associates, Inc. 14010 Poway Road, Suite A Poway, California 92064 (858) 484-0915 Report Date: August 23, 2018; Revised February 7, 2019 Report Title: A Phase I Cultural Resources Survey for the IDI Indian Avenue and Ramona Expressway Project, Perris, California Prepared for: Steve Hollis IDI Ramona, LLC 8 Corporate Park, Suite 300 Irvine, California 92606 Submitted to: City of Perris Planning and Development 135 North D Street Perris, California 92570 Submitted by: Brian F. Smith and Associates, Inc. 14010 Poway Road, Suite A Poway, California 92064 Assessor’s Parcel Number(s): 302-060-002, -005, -006, and -038, 302-050-034 and -036 USGS Quadrangle: Perris, California (7.5 minute) Study Area: 24.2-acre industrial site northwest of the intersection of Indian Avenue and the Ramona Expressway and 2.64-acre off-site improvement area Key Words: USGS Perris Quadrangle (7.5 minute); archaeological survey; positive; P-33-028621; no CEQA-significant resources. -

Historical/Archaeological Resources Survey Report

IDENTIFICATION AND EVALUATION OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES REPORT SAN JACINTO RIVER LEVEE PROJECT (STAGE 4) In and near the City of San Jacinto Riverside County, California For Submittal to: Community Development Department City of San Jacinto 595 S. San Jacinto Avenue, Building A San Jacinto, CA 92583 and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Los Angeles District 915 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90017 Prepared for: Sonya Hooker Albert A. Webb Associates 3788 McCray Street Riverside, CA 92506 Prepared by: CRM TECH 1016 East Cooley Drive, Suite A/B Colton, CA 92324 Michael Hogan, Principal Investigator Bai “Tom” Tang, Principal Investigator September 27, 2014 CRM TECH Contract No. 2845 Title: Identification and Evaluation of Historic Properties: San Jacinto River Levee Project (Stage 4), in and near the City of San Jacinto, Riverside County, California Author(s): Bai “Tom” Tang, Principal Investigator/Historian Daniel Ballester, Archaeologist/Field Director Nina Gallardo, Archaeologist/Native American Liaison Consulting Firm: CRM TECH 1016 East Cooley Drive, Suite A/B Colton, CA 92324 (909) 824-6400 Date: September 27, 2014 For Submittal to: Community Development Department City of San Jacinto 595 S. San Jacinto Avenue, Building A San Jacinto, CA 92583 (951) 487-7330 and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Los Angeles District 915 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90017 (213) 452-3840 Prepared for: Sonya Hooker Albert A. Webb Associates 3788 McCray Street Riverside, CA 92506 (951) 248-4263 USGS Quadrangles: Lakeview and San Jacinto, Calif., 7.5’ quadrangles;