Historic Resources Survey, Chula Vista, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICROCONTOS E OUTRAS MICROFORMAS Alguns Ensaios

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM MICROCONTOS E OUTRAS MICROFORMAS Alguns ensaios MMicrocontos.indbicrocontos.indb 1 226-09-20126-09-2012 119:33:529:33:52 MMicrocontos.indbicrocontos.indb 2 226-09-20126-09-2012 119:33:539:33:53 MICROCONTOS E OUTRAS MICROFORMAS Alguns ensaios ORGANIZADORES Cristina Álvares e Maria Eduarda Keating MMicrocontos.indbicrocontos.indb 3 226-09-20126-09-2012 119:33:539:33:53 MMicrocontos.indbicrocontos.indb 4 226-09-20126-09-2012 119:33:539:33:53 ÍNDICE 7 Introdução 11 “La coz de la mula”. Fronteras genéricas en Historias mínimas de Javier Tomeo Anna Sawicka 23 El título en la minifi cción de José María Merino. Ensayo de una tipología Begoña Díez Sanz 45 Nouveaux genres littéraires urbains. Les nouvelles en trois lignes contemporaines au sein des micronouvelles Cristina Álvares 59 Representaciones del Proceso en la microfi cción argentina contemporánea Émilie Delafosse 73 A ascensão do microconto brasileiro no início do século XXI Fabrina Martinez de Souza e Rauer Ribeiro Rodrigues MMicrocontos.indbicrocontos.indb 5 226-09-20126-09-2012 119:33:539:33:53 81 Macrocities/Microstories: A Brave New Digital World Gilles Bonnet 95 “A minha gata morreu. Agora já me posso suicidar”: microformas de Adília Lopes Gonçalo Duarte 109 Forme brève et nostalgie du récit dans L’autofi ctif d’Éric Chevillard Guillaume Bellon 131 Microcuento – Speed Dating literario Paulina Nalewajko 139 “Uma macieira que dá laranjas”: a microfi cção de Rui Manuel Amaral Rita Patrício -

San Diego Bay Watershed Management Area & Tijuana River

San Diego Bay Watershed Management Area & Tijuana River Watershed Management Area Copermittee Meeting Minutes October 23, 2018 10:00am-12:00pm County of San Diego, 5510 Overland Ave., Room 472, San Diego, CA 92123 Attendees: San Tijuana Organization Names Diego River Bay WMA WMA SDCRAA (Airport) Nancy Phu (Wood) X City of Chula Vista (CV) Marisa Soriano X City of Imperial Beach (IB) Chris Helmer X X City of La Mesa (LM) Joe Kuhn X Jim Harry X Joe Cosgrove X X City of San Diego (SD) Brianna Menke X Arielle Beaulieu X Stephanie Gaines X Joanna Wisniewska X X County of San Diego (County) Rouya Rasoulzadeh X X Dallas Pugh X Port of San Diego (Port) Stephanie Bauer X Matt Rich X X Wood Environment & Sarah Seifert X Infrastructure Solutions (Wood) Greg McCormick X D-Max Engineering, Inc. (D-Max) John Quenzer X X Dudek Bryn Evans X Members of the Public Michelle Hallack (Alta Environmental) - - 1. Call to order: 10:10am 2. Roll Call and Introductions Participants introduced themselves. 3. Time for public to speak on items not on the agenda Present members of the public declined the opportunity to speak. 4. Draft San Diego Bay FY20 budget The estimated budget for FY20 was discussed. The current FY20 estimate is conservative and assumes receiving water monitoring and the WQIP update would occur during the first year of the new permit term. The estimated budget is under the spending cap estimate, but is more than the FY19 budget since receiving water monitoring and the WQIP update are two items not included in this fiscal year’s (FY19) budget. -

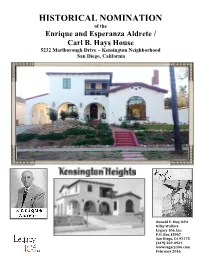

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge Sweetwater Marsh and South San Diego Bay Units Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement Volume I – August 2006 Vision Statement The San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge protects a rich diversity of endangered, threatened, migratory, and native species and their habitats in the midst of a highly urbanized coastal environment. Nesting, foraging, and resting sites are managed for a diverse assembly of birds. Waterfowl and shorebirds over-winter or stop here to feed and rest as they migrate along the Pacific Flyway. Undisturbed expanses of cordgrass- dominated salt marsh support sustainable populations of light-footed clapper rail. Enhanced and restored wetlands provide new, high quality habitat for fish, birds, and coastal salt marsh plants, such as the endangered salt marsh bird’s beak. Quiet nesting areas, buffered from adjacent urbanization, ensure the reproductive success of the threatened western snowy plover, endangered California least tern, and an array of ground nesting seabirds and shorebirds. The San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge also provides the public with the opportunity to observe birds and wildlife in their native habitats and to enjoy and connect with the natural environment. Informative environmental education and interpretation programs expand the public’s awareness of the richness of the wildlife resources of the Refuge. The Refuge serves as a haven for wildlife and the public to be treasured by this and future generations. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service California/Nevada Refuge Planning Office 2800 Cottage Way, Room W-1832 Sacramento, CA 95825 August 2006 San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) Sweetwater Marsh and South San Diego Bay Units Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement San Diego County, California Type of Action: Administrative Lead Agency: U.S. -

San Diego Bay Fish Consumption Study

CW San Diego Bay SC RP Fish Consumption Es 69 tablished 19 Study Steven J. Steinberg Shelly L. Moore SCCWRP Technical Report 976 San Diego Bay Fish Consumption Study Identifying fish consumption patterns of anglers in San Diego Bay Steven J. Steinberg and Shelly Moore Southern California Coastal Water Research Project March 2017 (Revised December 2017) Technical Report 976 TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Project Leads Southern California Coastal Water Research California Regional Water Quality Control Project (SCCWRP) Board, San Diego Region Tom Alo, Water Resource Control Engineer Dr. Steven Steinberg, Project Manager & Contract Manager Shelly Moore, Project Lead Brandman University Dr. Sheila L. Steinberg, Social Science Consultant Technical Advisory Group Members California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Regional Water Quality Control Alex Vejar Board, San Diego Region Chad Loflen California Department of Public Health Lauren Joe Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Pacific (SPAWAR) City of San Diego/AMEC Chuck Katz Chris Stransky State Water Resources Control Board County Department of Environmental Dr. Amanda Palumbo Health Keith Kezer University of California, Davis Dr. Fraser Shilling Environmental Health Coalition Joy Williams Unified Port of San Diego Phil Gibbons Industrial Environmental Association Jack Monger United States Environmental Protection Agency Recreational Fishing/Citizen Expert Dr. Cindy Lin Mike Palmer i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was prepared for and supported by funding from the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Diego Region; the San Diego Unified Port District; and the City of San Diego. We appreciate the valuable input and recommendations from our technical advisory group, Mr. Paul Smith at SCCWRP for his assistance in development of the mobile field survey application and database, our field survey crew (Mr. -

Downloadable Version

EDITORIAL BOARD Francisco Sóñora Luna. Director Magazine Raquel Troitiño Barros. Scholar Science Advisor Mercedes Mariño Paz. Translator and English Translation Advisor Gloria Rivas Rodríguez. Social English Communication Advisor Felipe Roget Salgado. Computer Advisor Aitor Alonso Méndez. Webmaster & Social Media - English Scientific Communication Advisor COVER DESIGN: Javier Sande Iglesias. E D IT ED B Y ISBN: 978-84-697-9954-3 * The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible INDEX STUDY, EDUCATION AND DIDACTICS FROM THE EXCELLENCE TO COMBAT CLIMATE CHANGE ................................................................................................................................... 1 SCIENCE AND SCHOOL I N THE FACE OF GLOBAL C H A N G E I N T H E O C E A N S ....................................................................................................................... 3 THEATRE AS AN EDUCAT I O N A L T O O L ............................................................ 5 EUROPEAN PROJECT “EduCO2cean” AT ALVES MARTINS SECONDARY SCHOOL (ESAM) – A PROJECT MEANT FOR TWO YEARS THAT PROMISES TO CONTINUE IN A DIFFERENT FORMAT ............................................................................................................... 45 EUTROPHICATION IN TH E BALTIC SEA – STATE AND EFFECTS .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cz39h5 Online items available The Descriptive Finding Guide for the Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078 Alan Renga San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives 10/23/2014 2001 Pan American Plaza, Balboa Park San Diego 92101 URL: http://www.sandiegoairandspace.org/ The Descriptive Finding Guide for SDASM.SC.10078 1 the Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives Title: Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers source: Jackson, Parker H. Identifier/Call Number: SDASM.SC.10078 Physical Description: 0.36 Cubic FeetOne Box Date (inclusive): 1913-2014 Abstract: Parker H. Jackson was the biographer Richard S. Requa, the master architect of the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. This Collection includes documents from Jackson's studies of Requa. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open to researchers by appointment. Conditions Governing Use Some copyright may be reserved. Consult with the library director for more information. Preferred Citation [Item], [Filing Unit], [Series Title], [Subgroups], [Record Group Title and Number], [Repository “San Diego Air & Space Museum Library & Archives”] Immediate Source of Acquisition The materials in this collection were donated to the San Diego Air & Space Museum. The collection has been processed and is open for research. Biographical / Historical Parker H. Jackson was the biographer Richard S. Requa, the master architect of the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. Jackson became fascinated with Requa and his influence on architectural design after purchasing a home designed by Requa located in the community of Kensington, in San Diego. -

The Sweetwater District Does Not Discriminate with Regard to Gender

The Sweetwater District does not discriminate with regard to gender, religion, color, national origin, ancestry/ethnicity, material or parental status, age, physical or mental disability, sexual orientation or any other unlawful consideration. SUHSD Board Policy #2224. No one is better than you, but you are no better than anyone else until you do something to prove it. Adelante Mujer . …….. because you are the past because you are the today, and because you are the future. ……. because you are the creator of our communities ……. Adelante, because your love and care is the strength of our lives. ……. because by being present today with your sisters, mothers, grandmothers, we create unity among ourselves ……. because today is a good day, everyday is a good day ……. because no matter how confused or puzzled you are, you will never be lost. ……. because the little girl inside of you wants to experience, develop, and create ……. because unity, strength and power is for the betterment of our community ……. because Today you will blossom and soon achieve all your goals ……. because you are the woman of the day – Everyday! 22nd Annual Adelante Mujer Conference, March 7, 2015 Real riches are the riches possessed inside. Adelante Mujer . MISSION STATEMENT The Adelante Mujer Steering Committee promotes Latinas' rights to determine their own destiny through personal, cultural, academic and professional development. PURPOSE • Expose Latinas to successful role models in a • Encourage Latinas to continue their wide variety of occupations. education. • Raise self-esteem and empower all • Encourage Latinas to pursue non-traditional participants in making positive decisions career paths. toward economic self-sufficiency. -

Se Han Incoado Cuatro Causas Por El Suceso Que

'' '' • • 1------------------------------------------- ------------------------------(COLUMNA UNA)+--- LO INCENDIO LA UNIVERSIDAD PIDE QUE FUSILEN A LOS MACl~ADISTAS COLUMNA TRES l-- Edición del MediodiL UNA DESCARGA ,----- MIMEROTECA •1 '-. EL EC TRI CA RESERVA centavo l>IR.~t,TOR SE ENFRENTO EL BARCO CON UNA TEMPESTAD A las seis de la mañana, \, ___________________TERRORISMO. (Vea Col. CUATRO) _ .J ACOGmo • l&A l'll&ll"lJtOU ro.. ~.u. • ll'ISCltil''lO COMO C;OBBBESPOHDEJl'OU DB SEG estaba el "Morro Castle" _convertido en l l a m a s -ANO l.- LA HABANA, SABADO 8 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 193-1 -NUM. 171- DESTRU-IDO EW YORK, Sep. 8.- La Opinión Pública Aspira a Acabar con el Gobierno de Mendieta 8 y 37 a. m.-(Por ------------ (Dijo Rodríguez Pintarlo). ---(COLUMNA DOS)--- N Cable de la U. P.) Los primeros reportes lle- gados a esta ciudad en r~ lación con el siniestro de que ha sido víctima el "Mtrro Castle", cuando PASAJEROS IIE ros C I EN ( -';JLUMNA UNO --- estaba a punto de llegar a est~ puerto, acusan más Al fin se celebró la anunciada Ayer llegó a la Habana, proceden Asamblea NacionaEsta, en la cual se EL ARTICULADO te de los Estados Unidos. a donde ha• prcdujo intensos debates, que die bía ido en misión especial de nuestro ron lugar a severas criticas al Go DE LA NUEVA gobierno (firma del nuevo tratado) bierno de la semi Concentración del nuestro «elegante• Secreta.rlo de Es Corone¡ Mendieta, y al mismo tiem LEY ELECTORAL tado, Don Cosme de J.a Torriente. Al po a defensa afectuosas de viejos desembarcar dijo a los periodistas que amigos del actual Presidente. -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME I: INVENTORIES OF HISTORIC BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES ON CALIFORNIA MILITARY INSTALLATIONS Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 Prepared by: FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Sacramento, California 95834 and JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March2000 Calirornia llisloric Miliiary Buildings and Structures Inventory, \'olume I CONTENTS Page CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................ ii TABLES ......................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................... viii SERIES INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ ix 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1-1 I. I Purpose and Goals ......................................................................................................