05-Culturalresourceassessment.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County of Riverside General Plan San Jacinto Valley Area Plan

County of Riverside General Plan San Jacinto Valley Area Plan COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE Transportation and Land Management Agency 4080 Lemon Street, 12th Floor Riverside, CA 92501-3634 Phone: (951) 955-3200, Fax: (951) 955-1811 October 2011 Page i County of Riverside General Plan San Jacinto Valley Area Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision Summary.......................................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A Special Note on Implementing the Vision ........................................................................................................ 2 Location ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Features ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Setting ....................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Unique Features ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 San Jacinto River ................................................................................................................................................ -

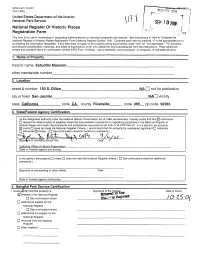

Ctffta Ignaljjre of Certifying Official/Title ' Daw (

NFS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register Of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Estudillo Mansion_____________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 150 S. Dillon________________ NA CH not for publication city or town San Jacinto____________________ ___NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Riverside. code 065_ zip code 92583 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this 12 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

3.8 Biological Resources

Section 3.8 – Biological Resources 3.8 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.8.1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this section is to identify existing biological resources within the planning area covered by the proposed project, analyze potential biological impacts, and recommend mitigation measures to avoid or lessen the significance of any identified adverse impacts. The assessment of impacts to biological resources is a qualitative review of the existing biological resources within the City and its SOI and a determination of whether the proposed project includes adequate provisions to ensure the protection of these resources. Given the programmatic nature of the PEIR, specific impacts to individual properties or areas are not identified or known at this time. 3.8.2 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING The information contained in this Environmental Setting section is primarily from information contained in the City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Background Reports (see Chapter 3 – Biological Resources). This document is attached as Appendix B to this PEIR. The City and SOI are located in the Elsinore Valley, which is generally bounded on the west by the east flank of the rugged Santa Ana Mountains and on the west by gently sloping hills. The San Jacinto River and Temescal Wash cut through the valley, converging at Lake Elsinore. The area contains a mixture of land developed for residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, and agricultural uses and undeveloped land remaining in its natural state. Approximately 16 natural vegetative communities, in addition to developed sites and agricultural uses, occur in the City and its SOI. Each of these habitats provides cover, food, and water necessary to meet biological requirements of a variety of animal species. -

Birds of the San Jacinto Valley Important Bird Area the San Jacinto Valley

Birds of the San Jacinto Valley Important Bird Area The San Jacinto Valley “Through this beautiful valley runs a good-sized river...on whose banks are large, shady groves... All its plain is full of fl owers, fertile pastures, and other vegetation.” So wrote Juan Bautista De Anza in 1774, describing the San Jacinto Valley as he came down from the mountains on his expedition from Tubac, Arizona, to San Francisco. When he came to what we now call Mystic Lake in the northern part of the valley, he wrote: “We came to the banks of a large and pleasing lake, several leagues in circum- ference and as full of white geese as of water, they being so numerous that it looked like a large, white glove.” It is clear from these early descriptions that the San Jacinto Valley has long been a haven for wildlife. While much of the valley has been developed over the years, the San Jacinto Valley is still amazingly rich with birds and other wildlife, and has the potential to remain so in perpetuity. This pamphlet describes a few of the many birds that make the San Jacinto Valley their home. Some species are rare and need protection, while others are common. Some migrate to the San Jacinto Valley from thousands of miles away, while others spend their entire lives within the confi nes of the valley. Our hope is that you get to know the birds of the San Jacinto Valley, and are moved to help protect them for future generations. 2 The San Jacinto Valley is the fl oodplain of the San Jacinto River in western Riverside County. -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This Chapter Presents an Overall Summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the Water Resources on Their Reservations

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This chapter presents an overall summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the water resources on their reservations. A brief description of each Tribe, along with a summary of available information on each Tribe’s water resources, is provided. The water management issues provided by the Tribe’s representatives at the San Diego IRWM outreach meetings are also presented. 4.1 Reservations San Diego County features the largest number of Tribes and Reservations of any county in the United States. There are 18 federally-recognized Tribal Nation Reservations and 17 Tribal Governments, because the Barona and Viejas Bands share joint-trust and administrative responsibility for the Capitan Grande Reservation. All of the Tribes within the San Diego IRWM Region are also recognized as California Native American Tribes. These Reservation lands, which are governed by Tribal Nations, total approximately 127,000 acres or 198 square miles. The locations of the Tribal Reservations are presented in Figure 4-1 and summarized in Table 4-1. Two additional Tribal Governments do not have federally recognized lands: 1) the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians (though the Band remains active in the San Diego region) and 2) the Mount Laguna Band of Luiseño Indians. Note that there may appear to be inconsistencies related to population sizes of tribes in Table 4-1. This is because not all Tribes may choose to participate in population surveys, or may identify with multiple heritages. 4.2 Cultural Groups Native Americans within the San Diego IRWM Region generally comprise four distinct cultural groups (Kumeyaay/Diegueno, Luiseño, Cahuilla, and Cupeño), which are from two distinct language families (Uto-Aztecan and Yuman-Cochimi). -

Water, Capitalism, and Urbanization in the Californias, 1848-1982

TIJUANDIEGO: WATER, CAPITALISM, AND URBANIZATION IN THE CALIFORNIAS, 1848-1982 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Hillar Yllo Schwertner, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 14, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Hillar Yllo Schwertner All Rights Reserved ii TIJUANDIEGO: WATER, CAPITALISM, AND URBANIZATION IN THE CALIFORNIAS, 1848-1982 Hillar Yllo Schwertner, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: John Tutino, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This is a history of Tijuandiego—the transnational metropolis set at the intersection of the United States, Mexico, and the Pacific World. Separately, Tijuana and San Diego constitute distinct but important urban centers in their respective nation-states. Taken as a whole, Tijuandiego represents the southwestern hinge of North America. It is the continental crossroads of cultures, economies, and environments—all in a single, physical location. In other words, Tijuandiego represents a new urban frontier; a space where the abstractions of the nation-state are manifested—and tested—on the ground. In this dissertation, I adopt a transnational approach to Tijuandiego’s water history, not simply to tell “both sides” of the story, but to demonstrate that neither side can be understood in the absence of the other. I argue that the drawing of the international boundary in 1848 established an imbalanced political ecology that favored San Diego and the United States over Tijuana and Mexico. The land and water resources wrested by the United States gave it tremendous geographical and ecological advantages over its reeling southern neighbor, advantages which would be used to strengthen U.S. -

California Gubernatorial Recall Election

County of Riverside CALIFORNIA GUBERNATORIAL RECALL ELECTION Registrar of Voters Tuesday, September 14, 2021 County Voter Information Guide Polling Places September 11-September 13 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. IMPORTANT! VOTING HAS CHANGED! DETAILS INSIDE Election Day, September 14 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Location on Back Cover Registration Deadline August 30, 2021 Quick • Easy • Convenient This election every voter receives a Vote-By-Mail ballot. Additional Information Inside Request Language Assistance Form on Back Cover to receive election material translated in available selected languages. AVISO IMPORTANTE Una traducción en Español de esta Guía de Información del Condado Para el Votante puede obtenerse en la oficina del Registro COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE REGISTRAR OF VOTERS de Votantes llamando al (951) 486- 7200 2720 Gateway Drive, Riverside, CA 92507-0918 o (800) 773-VOTE (8683) o visite nuestro (951) 486-7200 • (800) 773-VOTE (8683) • California Relay Service (Dial 711) Mailing Address: 2724 Gateway Drive, Riverside, CA 92507-0918 sitio web www.voteinfo.net www.voteinfo.net THIS ELECTION VOTING IS DIFFERENT VOTE-BY-MAIL Vote at home using your Vote-By-Mail ballot No Postage Required Quick, easy, convenient... from the comfort of your home! OR BALLOT DROP-OFF LOCATION Drop off your ballot at any of the Ballot Drop-off locations in Riverside County No Postage Required See inside... for a list of drop-off locations throughout Riverside County! OR POLLING PLACE Vote in-person at Your Assigned Polling Place in Riverside County September 11- September 13, from 9:00 a.m. -

Geologic Map of the Lakeview 7.5' Quadrangle, Riverside

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Eastern Municipal Water District and the CALIFORNIA DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OPEN-FILE REPORT 01-174 Version 1.0 117 7' 30" 117 00' CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS 3 52' 30" 33 52' 30" MODERN SURFICIAL DEPOSITS—Sediment recently transported and Kmeg Granite of Mount Eden (Cretaceous)—Granite to monzogranite; white to gray, grain-size, rare schlieren, and more abundant, more attenuated inclusions. Age Qw Qf Qv Qc Qlv deposited in channels and washes, on surfaces of alluvial fans and alluvial plains, leucocratic, medium- to coarse-grained, commonly foliated. Contains relation to Lakeview Mountains pluton is ambiguous. Small mass of tonalite and on hillslopes. Soil-profile development is non-existant. Includes: muscovite, garnet, and almost no mafic minerals. Restricted to northeastern resembling Lakeview Mountains tonalite occurs within the Reinhardt Canyon Qyf6 Qw Very young wash deposits (late Holocene)—Deposits of active alluvium; confined part of quadrangle where it occurs as dikes and irregular masses emplaced pluton near the contact, but is not clear whether it is inclusion or intrusion of to San Jacinto River channel. Consists mostly of unconsolidated sand in along foliation in metamorphic rocks; also as southernmost part of small pluton Lakeview Mountains rock. Similar appearing tonalite north of Lakeview Qyf5 ephemeral, engineered river channel. Prior to agricultural development, that extends into quadrangle to north Mountains is correlated with Reinhardt Canyon pluton Holocene position of river channel was north of current engineered channel. Sediment Mixed metamorphic rocks and granitic rocks (Cretaceous and Qyf4 Klt Tonalite of Laborde Canyon (Cretaceous)—Biotite-hornblende tonalite. -

Journal of Sd History

T HE J OURNAL OF SANDIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/ SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY MCCLAIN Editors COLIN R. FISHER DAWN M. RIGGS Review Editors MATTHEW BOKOVOY Contributing Editor Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 81825, San Diego, California 92138 ISSN 0022-4383 T HE J OURNAL OF SAN DIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the MATTHEW BOKOVOY San Diego Historical Society at University of Oklahoma 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 DONALD C. CUTTER Albuquerque, New Mexico A $50.00 annual membership in the San WILLIAM DEVERELL Diego Historical Society includes subscrip- University of Southern California; Director, Huntington-USC Institute on California tion to The Journal of San Diego History and and the West the SDHS Times. Back issues and microfilm copies are available. VICTOR GERACI University of California, Berkeley Articles and book reviews for publication PHOEBE KROPP consideration, as well as editorial correspon- University of Pennsylvania dence should be addressed to the ROGER W. LOTCHIN Editors, The Journal of San Diego History University of North Carolina Department of History, University of San at Chapel Hill Diego, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA NEIL MORGAN 92110 Journalist DOYCE B. NUNIS, JR. All article submittals should be typed and University of Southern California double spaced, and follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors should submit four JOHN PUTMAN San Diego State University copies of their manuscript, plus an electronic copy, in MS Word or in rich text format ANDREW ROLLE (RTF). -

Journal of San Diego History V 50, No 1&2

T HE J OURNAL OF SANDIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/ SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY MCCLAIN Editors COLIN FISHER DAWN M. RIGGS Review Editors MATTHEW BOKOVOY Contributing Editor Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 81825, San Diego, California 92138 ISSN 0022-4383 T HE J OURNAL OF SAN DIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the MATTHEW BOKOVOY San Diego Historical Society at University of Oklahoma 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 DONALD C. CUTTER Albuquerque, New Mexico A $50.00 annual membership in the San WILLIAM DEVERELL Diego Historical Society includes subscrip- University of Southern California; Director, Huntington-USC Institute on California tion to The Journal of San Diego History and and the West the SDHS Times. Back issues and microfilm copies are available. VICTOR GERACI University of California, Berkeley Articles and book reviews for publication PHOEBE KROPP consideration, as well as editorial correspon- University of Pennsylvania dence should be addressed to the ROGER W. LOTCHIN Editors, The Journal of San Diego History University of North Carolina Department of History, University of San at Chapel Hill Diego, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA NEIL MORGAN 92110 Journalist DOYCE B. NUNIS, JR. All article submittals should be typed and University of Southern California double spaced, and follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors should submit four JOHN PUTMAN San Diego State University copies of their manuscript, plus an electronic copy, in MS Word or in rich text format ANDREW ROLLE (RTF).