A Model of Lexical Variation and the Grammar with Application to Tagalog Nasal Substitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga

Heritage Voices: Language - Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga About the Tagalog Language Tagalog is a language spoken in the central part of the Philippines and belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian language family. Tagalog is one of the major languages in the Philippines. The standardized form of Tagalog is called Filipino. Filipino is the national language of the Philippines. Filipino and English are the two official languages of the Philippines (Malabonga & Marinova-Todd, 2007). Within the Philippines, Tagalog is spoken in Manila, most of central Luzon, and Palawan. Tagalog is also spoken by persons of Filipino descent in Canada, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In the United States, large numbers of Filipino immigrants live in California, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Washington (Camarota & McArdle, 2003). According to the 2000 US Census, Tagalog is the sixth most spoken language in the United States, spoken by over a million speakers. There are about 90 million speakers of Tagalog worldwide. Bessie Carmichael Elementary School/Filipino Education Center in San Francisco, California is the only elementary school in the United States that has an English-Tagalog bilingual program (Guballa, 2002). Tagalog is also taught at two high schools in California. It is taught as a subject at James Logan High School, in the New Haven Unified School District (NHUSD) in the San Francisco Bay area (Dizon, 2008) and as an elective at Southwest High School in the Sweetwater Union High School District of San Diego. At the community college level, Tagalog is taught as a second or foreign language at Kapiolani Community College, Honolulu Community College, and Leeward Community College in Hawaii and Sacramento City College in California. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Tagalog As Spoken In

Language specific peculiarities Document for Tagalog as Spoken in the Philippines 1. Dialects Tagalog is spoken by around 25 million1 people as a first language and approximately 60 million as a second language. It is the local language spoken by most Filipinos and serves as a lingua franca in most parts of the Philippines. It is also the de facto national language of the Philippines together with English. Although officially the name of the national language is "Filipino", which has Tagalog as its basis, the majority of Filipinos are unaccustomed, even unaware, of this naming convention. Practically speaking, the name "Tagalog" is used by many Filipinos when referring to the national language. "Filipino", on the other hand, is rather ambiguous and, it must be said, carries nationalistic overtones2. The population of Tagalog native speakers is primarily concentrated in a region that covers southern Luzon and nearby islands. In this project, three major dialectal regions of Tagalog will be presented: Dialectal Region Description North Includes the Tagalog spoken in Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija and parts of Zambales. Central The Tagalog spoken in Manila, parts of Rizal and Laguna. This is the Tagalog dialect that is understood by the majority of the population. South Characteristic of the Tagalog spoken in Batangas, parts of Cavite, major parts of Quezon province and the coastal regions of the island of Mindoro. 1.1. English Influence The standard Tagalog spoken in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is also considered the prestige dialect of Tagalog. It is the Tagalog used in the media and is taught in schools. -

The Languages of Nusa Tenggara: Pan Reconstruction and Subgrouping

The Languages of Nusa Tenggara: PAn Reconstruction and Subgrouping Peter Norquest University of Arizona [email protected] 6/2/12 0.0 Introduction • The majority consensus on the demographic history of the speakers of the Austronesian family of languages is that they originated on Taiwan (after having migrated from southern China), and proceeded through insular Southeast Asia. • This migration model crucially predicts that linguistic innovations at any point along the migration path must carry over into subsequent areas of dispersal. with phonological mergers (and lexical replacements) being unrecoverable once they have occurred. • The distinctions between *C and *t, *S and *h, and *N and *n have only been recognized in the Formosan languages of Taiwan, having merged in all extra-Formosan Austronesian languages. 0.1 The Problem • A group of phonological distinctions have been preserved in the Nusa Tenggara (NT) region (which coincides with the Central Malayo-Polynesian node of the above tree), the majority of which have not been preserved in the Formosan languages. • Several of these distinctions appear to have also been preserved in other parts of the Malayo-Polynesian area. Here, we will be concerned with the Macro-Sumba subgroup. which includes the languages of Sumba. Savu, Dhao. and Bimanese (spoken in eastern Sumbawa): [Proto-Sumba [Bimanese [Savu-Dhao 111 0.2 The Present State of Austronesian reconstruction The consensus inventory of PAn consonants is the following: (I) p t C c k q ? b d j z g s S h m n )1 1] N w r R y *C, *j, *z, *s, *S. -

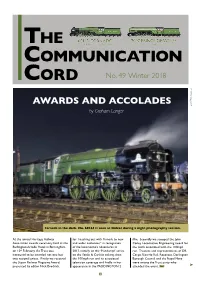

Didcot Railway CENTRE

THE COMMUNICATION ORD No. 49 Winter 2018 C Shapland Andrew AWARDS AND ACCOLADES by Graham Langer Tornado in the dark. No. 60163 is seen at Didcot during a night photography session. At the annual Heritage Railway for “reaching out with Tornado to new film. Secondly we scooped the John Association awards ceremony held at the and wider audiences” in recognition Coiley Locomotive Engineering award for Burlington Arcade Hotel in Birmingham of the locomotive’s adventures in the work associated with the 100mph on 10th February, the Trust was 2017, initially on the ‘Plandampf’ series run. Trustees and representatives of DB honoured to be awarded not one but on the Settle & Carlisle railway, then Cargo, Ricardo Rail, Resonate, Darlington two national prizes. Firstly we received the 100mph run and its associated Borough Council and the Royal Navy the Steam Railway Magazine Award, television coverage and finally in her were among the Trust party who ➤ presented by editor Nick Brodrick, appearance in the PADDINGTON 2 attended the event. TCC 1 Gwynn Jones CONTENTS EDItorIAL by Graham Langer PAGE 1-2 Mandy Gran Even while Tornado Awards and Accolades up his own company Paul was Head of PAGE 3 was safely tucked Procurement for Northern Rail and Editorial up at Locomotive previously Head of Property for Arriva Tornado helps Blue Peter Maintenance Services Trains Northern. t PAGE 4 in Loughborough Daniela Filova,´ from Pardubice in the Tim Godfrey – an obituary for winter overhaul, Czech Republic, joined the Trust as Richard Hardy – an obituary she continued to Assistant Mechanical Engineer to David PAGE 5 generate headlines Elliott. -

The Linguistic Ecology of Lombok, Eastern Indonesia

2018-06-01 Uppsala University Workshop Sasak, eastern Indonesia: layers of language contact and language change Peter K. Austin Linguistics Department, SOAS University of London Many thanks to Berndt Nothofer for sharing his Sasak materials and research on etymologies, and to colleagues in Lombok for assistance with data and analysis, especially Lalu Dasmara, Lalu Hasbollah and Sudirman. Key points of today’s talk ◼ The history and sociology of Lombok, eastern Indonesia has led to complex lexical borrowings from languages to the west through the innovation of a speech levels system ◼ Earlier believed the ‘core vocabulary’ (body parts, kinship, numbers, pronouns) was immune from borrowing but not here ◼ Sasak has innovated new non-etymological non- borrowed material through a kind of system pattern borrowing Outline ◼ Geography and History ◼ Population and Sociology ◼ Language variation ◼ Contact phenomena ◼ Conclusions Indonesia Data collection Lombok history ◼ Majapahit dependency (13th-15th century) Lombok history ◼ Borrowed Javanese cultural traditions: caste system, aristocracy, Hindu-Buddhist cultural concepts and practices, literacy ◼ Influence of Makassarese (east Lombok) and Balinese (west Lombok) from 16th century ◼ 1678 Balinese Gegel drive out Makassarese, 1740 Balinese Karangasem conquer Gelgel, dominate all Lombok ◼ Introduction of priesthood, books, Aksara Sasak, reinforcement of Javanese influences ◼ Karangasem-Lombok enhanced court by collecting greatest works of the Balinese and Javanese literature, centre of literary -

Tagbanua Language in Irawan in the Midst of Globalization Teresita D

Tagbanua Language in Irawan in the Midst of Globalization Teresita D. Tajolosa Palawan State University Tessie_Tajolosa@ yahoo.com Abstract The purpose of this study was to investigate the Tagbanua language as a potentially endangered language in Irawan alone. Focusing on the language attitude, language use and actual language proficiency of the Tagbanua inhabitants, the researcher was interested in determining how these may be affected by the respondents’ characteristics such as age, sex, education and geographical location. Social factors such as intermarriage and stereotyping which may influence the perpetuation or decline of the language were also examined. The respondents included young and adult speakers from Sitio Iratag, Sitio Tagaud and lowland Irawan. To determine the language attitude and language use of the respondents, the researcher administered a set of questionnaire. For actual language proficiency, two native speakers of Tagbanua were hired to do interviews with the respondents. The paper ends with an outlook of how the Tagbanua language can be maintained by its speakers. 1.Introduction A surge of interest in sociolinguistics has been taking place during the past decades. Among the focus of many studies from different parts of the world are language loss, language identity and language survival. Despite the tug of war between the value of bilingualism and the survival of minority languages, supporters of indigenous language survival remain very vocal in their call for the continuous widespread of the language. This is due to the fact that “the threat to linguistic resources is now recognized as a worldwide crisis” (Crawford, 1998, http://our worldcompuserve.com/homepages/JW CRAWFORD/brj.htm ). -

Folklore As a Tool to Naturally Learn and Maintain Sasak Language As Mother Tongue

Folklore as a Tool to Naturally Learn and Maintain Sasak Language as Mother Tongue Nuriadi Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, University of Mataram, Majapahit Street No.62, Mataram Keywords: Folklore, Maintenance, Sasak Language, Mother Tongue. Abstract: This paper discusses the role of function of Sasak folklore, especially verbal folklores, in teaching and maintaining Sasak language naturally. ‘Sasak’ is a name of an ethnic group exisiting in Lombok island using Sasak language as mother tongue. Based on qualitative research, Sasak people is usually ‘planting’ (teaching) the Sasak language as their mother tongue through folklore, especially verbal Sasak folklores. Those are such as: pinje panje, children playing songs (elate), lullabying songs (bedede), or story telling (waran). This activity mostly happens in informal form in any kind of occasions. This phenomenon is usually undergone by mothers to their children or by other children to their friends in their own communities. Hence, it is also found that this model of learning is very effective in maintaining the Sasak language as mother tongue and Sasak culture. Finally, based on the research, most of the informants acknowledge that they still well remember all the folklores they played in childhood. They even still love their Sasak backgrounds. Therefore, Sasak folklore is a good tool in naturally teaching and/or maintaining Sasak language. 1 INTRODUCTION taking a role as mother-tongue for that group. It is embedded, according to Sairin (2010), in the vein of Language is as a culture and identity as well for each the real users and functions as a determinant of ethnic group (Sairin, 2010). -

The Bungku-Tolaki Languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia

The Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Mead, D.E. The Bungku-Tolaki languages of south-eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia. D-91, xi + 188 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D91.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

The Heritage Language Acquisition and Education of an Indigenous Group in Taiwan: an Ethnographic Study of Atayals in an Elementary School

THE HERITAGE LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND EDUCATION OF AN INDIGENOUS GROUP IN TAIWAN: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF ATAYALS IN AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BY HAO CHEN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Secondary and Continuing Education in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Mark Dressman, Chair Professor Sarah McCarthey Professor Liora Bresler Assistant Professor Wen-Hao Huang ABSTRACT In this study, I used ethnographic methods to investigate the learning and education of the heritage language of a group of indigenous students in Taiwan. Traditionally, their heritage language, Atayal, was not written. Also, Atayal was taught at schools only recently. As one of Austronesian language families, Atayal language and culture could have been part of the origin of other Polynesians in the Pacific Islands. Furthermore, as an Atayal member I was interested in knowing the current status of Atayal language among the Atayal students in school. I also wanted to know the attitudes of Atayal learning of the participants as well as how they saw the future of Atayal language. Last, I investigated the relationship of Atayal language and Atayal cultures. I stayed in an Atayal village in the mid mountain area in Taiwan for six months to collect observation and interview data. The research site included the Bamboo Garden Elementary School and the Bamboo Garden Village. In the 27 Atayal students who participated in this study, 16 were girls and 11 were boys. They were between Grade 2 to Grade 6. -

Documenting Endangered Literary Genres in Sasak, Eastern Indonesia

Documenting endangered literary genres in Sasak, eastern Indonesia Peter K. Austin Endangered Languages Academic Programme Department of Linguistics, SOAS ANDC, Australian National University [email protected] 2013-01-30 Draft paper prepared for Indonesian Linguistics Workshop, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, February 2013 – do not quote or cite without permission Abstract1 The island of Lombok, eastern Indonesia, is linguistically and culturally complex, with several languages being used there, including Sasak, Balinese, Kawi (a form of early modern Javanese) and Indonesian. Sasak shows wide geographical and social variation, with a system of speech levels, apparently borrowed from its western neighbours. The Sasaks also have a literary tradition of writing manuscripts on palm leaves (lòntar) in a manner similar to that of the Balinese (Rubinstein 2000, Creese 1999), and historically, the Javanese. Lombok today remains one of only a handful of places in Indonesia where reading lòntar (called in Sasak, pepaòsan) continues to be practised, however even there the number of people who are able to read and interpret the texts is rapidly diminishing. In this paper I outline the nature of the Sasak literary materials (see also Marrison 1999, 2000, Van der Meij 1996, 2002), how reading is taught, the nature of reading performances, and the role of this genre within contemporary Sasak culture. This work results from fieldwork undertaken in two locations on Lombok, and studies I have carried out with some of the few younger specialists who is able to perform lòntar reading. The paper concludes with discussion of some challenges for language documentation theory and practice (Himmelmann 2002, Woodbury 2011) that arise in the process of recording and analyzing 1 Research on Sasak has been supported at various times by the Australian Research Council, the School of Oriental and African Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung. -

Tagalog Language Maintenance and Shift Among the Filipino Community in New Zealand

Tagalog Language Maintenance and Shift among the Filipino Community in New Zealand Ronalyn Magadia Umali A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Communication Studies 2016 School of Communication Studies Table of Contents ABSTRACT iv LIST OF TABLES v ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Background to the study 1 1.2. Aims and significance of the study 2 1.3. Structure of the thesis 3 CHAPTER TWO: LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AND SHIFT 5 2.1. Language Contact, Maintenance, and Shift 5 2.1.1. Domains: where language is used 6 2.1.2. Reversing Language Shift, Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale and Ethnolinguistic Vitality 7 2.1.3. Attitudes and behaviours 9 2.1.4. Challenges to RLS, GIDS, and Ethnolinguistic Vitality 11 2.1.5. Non-traditional approaches to multilingualism 12 2.2. New Zealand and its Languages 13 New Zealand language maintenance and shift studies 14 2.3. The Philippines and its Languages 17 Filipino migrants and language maintenance/shift patterns 18 2.4. Chapter summary 21 CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY 22 3.1. Guiding perspective of the research 22 3.2. Research Design 23 3.3. Research Instruments 24 3.3.1. Informal observations 24 3.3.2. Interviews 25 3.4. Sampling 26 3.5. Thematic Analysis 27 3.6. Chapter summary 28 CHAPTER FOUR: THE TAGALOG LANGUAGE IN NEW ZEALAND 29 4.1. Filipinos and Tagalog language in New Zealand 29 4.2. Participants‘ demographics 32 4.2.1.