The Role of Pedagogy in Developing Life Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

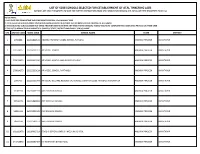

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Annual Report 1983-84

ANNUAL REPORT (1983-84) A NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL PLANNING AND ADMINISTRATION 17-B, SRI AUROBINDO MARG NEW DELHI APRIL 1985 ©NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL PLANNING AND ADM INISTRATION, 1985 Natif A t ' p U m i 4 17-B, ^ DOC, No I - ' Edited, Designed and Printed by Balakrishna Selvaraj, Publication Officer, National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, 17-B, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi-110016 printed at Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd., A-104 Mayapuri, Phase 11, New Delhi 110064 CONTENTS Page Objectives Acknowledgements An Overview 1 - 19 PART I : TRAINING PROGRAMMES 20 - U\ PART II : RESEARCH AND STUDIES hi - 72 PART III : ADVISORY, CONSULTANCY AND SUPPORT SERVICES 73 - 87 PART IV : OTHER ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES 88 - 93 PART V : ACADEMIC UNITS 9^ - 102 PART VI : ACADEMIC INFRASTRUCTURE 103 - 112 PART VII : ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 113 - 126 ANNEXURES I. Training Programmes 127 - 161 II. Research Studies 162 - 185 III. Academic Contribution of Faculty 186 - 207 IV. Visitors 208 - 209 APPENDICES I. List of Members of the Council of NIEPA 210 - 212 II. List of Members of the Executive 213 Committee of NIEPA III. List of Members of Finance Committee of NIEPA IIU IV. List of Members of the Programme Advisory 215 Committee of NIEPA V. List of Members of the Publication 216 Advisory Committee of NIEPA VI. List of Faculty and Research Staff of NIEPA 217 - 219 VII. Annual Accounts and Audit Report 220 - 258 THE AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE INSTITUTE (a) To organise pre-service and in-service training, conferences, workshops, -

Content S.No

CONTENT S.NO. TOPIC PAGE NO. 1. About Jaiprakash Sewa Sansthan 01 2. Our Motto, Mission & Vision 02 3. Our Pedagogy 03 4. Grooming a JPS Student 04 5. Mentoring Programmes 05 6. Personal Details of the Student 06-07 7. List of Holidays, Vacations and Breaks 08 8. School Fact Sheet & School’s Schedule 09 9. School Facilities 10 10. Transport Facilities 11-12 11. Academic Calendar 13-14 12. School Uniform and Dress Code 15 13. Examination Policy 16-17 14. Examination Schedule 18-20 15. Activity Calendar 21-25 16. Code of Conduct 26-27 17. Attendance, Withdrawal & Payment Rules 28-29 18. Activity Clubs 30-32 19. House System 33 20. Prayers 34-38 21. Home Work / Activities - ANNEXURES a. Visits to Infirmary b. Record of Leaves c. Record of Achievements d. Record of Books Read e. Defaulter Record f. Time Table ABOUT- JAIPRAKASH SEWA SANSTHAN (CSR WING OF JAYPEE GROUP) Jaiprakash Sewa Sansthan (JSS), a ‘not-for-profit trust ‘was registered in 1961 to reduce the pain and distress in the society. Set up in 1993, the trust firmly believes that Education is a powerful force for social change as it empowers the individuals, enriches communities and ultimately uplifts societies. The Sansthan has built a rich heritage in the field of quality education with a holistic approach for overall socio-economic development. It currently offers education through 28 schools, 5 ITCs, 2 polytechnic colleges, 2 post graduate colleges and 3 technical universities catering the needs of more than 30,000 students across the country with an objective to equip at least one lac students with the power of education by 2020.All these institutions strive to inculcate discipline and character building along with serious pursuit of knowledge utilizing the most advanced teaching practices and high moral standards, to reflect the motto ‘Humility Enhances Excellence’. -

Language As Identity in Colonial India

Language as Identity in Colonial India “The Indian awakening, our distinctive path to independence as Sengupta recalls, envisaged quilts of interwoven languages expressing a rich, multi-textured land- scape. British rule used tools of colonial enumeration like the census to compart- mentalize Indians into sharply separated languages and religions along Westphalian lines. Naive nationalistic unity-mongering today – Sengupta argues – inadvertently reinforces colonial compartmentalization, losing sight of that very landscape we must cherish and strengthen to achieve the uniquely Indian take-off we are des- tined for. A compelling argument.” —Prof. Probal Dasgupta, Head, Linguistics, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata “Papia Sengupta draws our attention to a very serious concern as how non-recog- nition of linguistic identity can become a source of discrimination, violence, harassment and torture. It is this action of submerging the diversity and plurality that brings in chaos and disturbance in Indian society. Her book may serve as a wakeup call to the Indian administration which is happy to forget that the stron- gest ecosystems in the world are those which are most diverse.” —Prof. Anvita Abbi (Padma Shri), Adjunct Professor, Simon Fraser University, B.C. Vancouver, Canada “Multilingualism has been a long-standing characteristic of Indian society, and its persistence during the post-colonial era is not surprising. What is surprising though is the transformation in the Indian sense of identity, the nation's self-perception, during the colonial period. Dr. Sengupta's well documented study reveals the sequential emergence of the linguistically embedded sense of identity brings home the new burden that language is brought to carry in the nation-India. -

Faculty Newsletter Winter 2007

California Association of Independent Schools Faculty Newsletter Winter 2007 STEPPING OUTSIDE THE KNOWN INSIDE: What I Did This Summer, Or Practice What You Preach Finding Mr. Potato Head Differentiated Instruction Makes a Difference Meditating on Mindfulness ...and more Faculty Newsletter Winter 2007 From the Editor robably “risk-takers” is not the first phrase we would use in describing ourselves and our profession. Rob Evans PP (Family Matters and The Human Side of Change), a former teacher himself, once compared us to “artisans in [our] separate studios, “doing work that is “idiosyncratic and unpredictable,” often requiring of us a talent for “spur-of- the-moment improvisation.” Frankly, those sound like attributes of risk-takers to me. Every day we step in front of our classes, or try a new activity we are, at least to some extent, venturing into the unknown. We may not be Xtreme athletes or venture capitalists, but unpredictability, improvisation, and training our sights beyond what we know to meet the needs of our students always involves the element of risk. Each of our authors in this issue tells a story about stepping out beyond the known in some way, whether in expanding their knowledge and skills in summer professional development work, then returning to classrooms to apply (and sometime teach their colleagues!) what they’ve learned, or initiating new programs in their schools. Sometimes this means we have to go beyond our personal comfort levels, as Cynthia Crass describes in her article about learning new acting techniques; sometimes it involves a hard look at our own practice, as Laura Holmgren, also a teacher at Polytechnic School, demonstrates. -

NAAC LSR-PART 1 (12-11-2015).Pmd

LADY SHRI RAM COLLEGE FOR WOMEN University of Delhi DEPARTMENT PROFILES 2015 SUBMITTED TO NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE May Brahman protect us both The Preceptor and the Disciple May it nourish us both May this energy inspire us towards knowledge May we become illumined by our learning May love and harmony dwell amongst us May peace abide. – College Prayer Sá vidyá yá vimuktaye That alone is knowledge which leads to liberation – College Motto II III May Brahman protect us both The Preceptor and the Disciple May it nourish us both May this energy inspire us towards knowledge May we become illumined by our learning May love and harmony dwell amongst us May peace abide. – College Prayer Sá vidyá yá vimuktaye That alone is knowledge which leads to liberation – College Motto II III CONTENTS NAAC Steering Committee: Principal: Introduction ..............................................................................................VI Dr. Suman Sharma Acknowledgements ...................................................................................X Members: Abbreviations .........................................................................................XII Dr. Priti S. Dhawan-Convenor Dr. Krishna Menon-Convenor Principal’s Profile........................................................................................1 Dr. Divya Misra-Convenor Dr. Kanika K. Ahuja Department Profiles Dr. Madhu Grover • Department of Commerce..................................................................7 Ms. Rukshana Shroff -

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950) Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was the first Deputy Prime Minister of India. He was an Indian barrister and statesman, a leader of the Indian National Congress and a founding father of the Republic of India who played a leading role in the country's struggle for independence and guided its integration into a united, independent nation. In India and elsewhere, he was often addressed as Sardar, which means Chief in Hindi, Urdu, and Persian. Patel was born in Gujjar family and raised in the countryside of Gujarat. He was employed in successful practice as a lawyer. He subsequently organised peasants from Kheda, Borsad, and Bardoli in Gujarat in non-violent civil disobedience against oppressive policies imposed by the British Raj, becoming one of the most influential leaders in Gujarat. He rose to the leadership of the Indian National Congress, in which capacity he organised the party for elections in 1934 and 1937 even as he continued to promote the Quit India Movement. As the first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister of India, Patel organised relief efforts for refugees fleeing from Punjab and Delhi and worked to restore peace across the nation. He led the task of forging a united India, successfully integrating into the newly independent nation those British colonial provinces that had been "allocated" to India. Besides those provinces that had been under direct British rule, approximately 565 self-governing princely states had been released from British suzerainty by the Indian Independence Act of 1947. Employing frank diplomacy with the expressed option to deploy military force, Patel persuaded almost every princely state to accede to India. -

Schcd Schname Init Year Schpass Status Vilcd 24010102001 SHRI

schcd schname Init_Year SchPass status Vilcd SHRI GOVERNMENT HIGH 24010102001 SCHOOL,KAPURASI 2008-09 kprasi 2 240101020 24010102301 GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 GOV301 2 240101023 24010102302 SHRI SYAMJIKRISHNVARMA VIDHYALA 2008-09 SHR302 2 240101023 SHRI SYAMJIKRISHNVARMA SECONDARY 24010102303 SCHOOL 2008-09 SHR303 2 240101023 24010102801 GOVERMENT HIGH SCHOOL GHADULIU 2008-09 GOV801 2 240101028 24010103901 GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 GOV901 2 240101039 24010104501 SARSWATAM SANCHALIT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 SAR501 2 240101045 24010104701 SHRI GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL,HARODA 2008-09 haroda 2 240101047 24010104901 AMIR FAISAL U.B. HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 AMI901 2 240101049 SHRI GOVERNMENT HIGH 24010106501 SCHOOL,BARANDA 2008-09 barnda 2 240101065 24010110001 SHREE BHADARA MADHAYMIK SHALA 2008-09 SHR001 2 240101100 24010200101 SHRI SARASHVATI VIDYALAY 2008-09 SHR101 2 240102001 24010200301 NUTAN VIDYALAYA 2008-09 NUT301 2 240102003 24010200501 SHREE GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOL 2008-09 SHR501 2 240102005 24010201401 SHREE SARVAJNIC VIDYALAY GEDI 2008-09 SHR401 2 240102014 24010201501 GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 GOV501 2 240102015 24010202101 SANDIPANI VIDYA MANDIR 2008-09 SAN101 2 240102021 24010202401 SHREE GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 SHR401 2 240102024 24010202901 GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL 2008-09 GOV901 2 240102029 24010203901 GOVERNMENT SCHOOL MODA 2008-09 GOV901 2 240102039 24010204201 UTTAR BUNIYADI VIDYALAYA 2008-09 UTT201 2 240102042 SHRI GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY 24010204202 SCHOOL,ADESAR 2008-09 adesar 2 240102042 24010204501 -

Twinned Schools

QT4TT dial u L131 GI SAMAGRA SHIKSHA OFFICE OF THE U.E.E. MISSION (A Society Under Education Department, Govt. of NCT of Delhi) Lucknow Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph.23810361, 23810647, Tele Fax:-011 23811442 Email:[email protected] No: - UEEM/Twinning of Schools/Admn./2019/S+.1-4-811•4.—liate:- 1D 2 CIRCULAR SUB:- Twinning of Schools Samagra Shiksha, an Integrated Scheme for School Education-Framework for Implementation, MHRD, Department of School Education and Literacy, in Chapter 5- Quality Interventions, lists Twinning of schools as one of the Quality Interventions, that can help in transforming the school ecosystem through sharing of resources and best practices. Rationale for Twinning Programme 2. The rationale behind this innovative programme is that it offers a powerful alternative to four walled classroom chalk and talk method. It aims to explore new dimensions of learning which will provide and enable the students to understand and respect cultural differences and help in creating committed, disciplined and productive individuals. Objectives of twinning programme: 3. The major objectives of the programme are: a. To bring all students on one common platform; b. Enable both the partner schools to adopt best practices from each other; c. Share experiences and learn jointly d. Develop the spirit of Comradeship e. Get an exposure to the strength and weakness of self and others; f. Provide opportunities to the teaching fraternity to adopt better and more effective practices; g. Develop a sense of interdependence and understanding towards each other; h. Recognize the gaps and make efforts to bridge them; i. Instil a spirit of sharing, caring and togetherness, etc. -

No: - UEEM/Twinning of Schools/Admn./2019/ 2,-1-4-4—Saq4___Date:-2412

2i cl 1. 1-49T 3.114" Tra- csa SAMAGRA SHIKSHA OFFICE OF THE U.E.E. MISSION (A Society Under Education Department, Govt. of NCT of Delhi) Lucknow Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph.23810361, 23810647, Tele Fax:-011 23811442 Email:[email protected] No: - UEEM/Twinning of Schools/Admn./2019/ 2,-1-4-4—Saq4___Date:-2412 CIRCULAR SUB:- Twinning of Schools Samagra Shiksha, an Integrated Scheme for School Education-Framework for Implementation, MHRD, Department of School Education and Literacy, in Chapter 5- Quality Interventions, lists Twinning of schools as one of the Quality Interventions, that can help in transforming the school ecosystem through sharing of resources and best practices. Rationale for Twinning Programme 2. The rationale behind this innovative programme is that it offers a powerful alternative to four walled classroom chalk and talk method. It aims to explore new dimensions of learning which will provide and enable the students to understand and respect cultural differences and help in creating committed, disciplined and productive individuals. Objectives of twinning programme: 3. The major objectives of the programme are: a. To bring all students on one common platform; b. Enable both the partner schools to adopt best practices from each other; c. Share experiences and learn jointly d. Develop the spirit of Comradeship • a Get an exposure to the strength and weakness of self and others; f. Provide opportunities to the teaching fraternity to adopt better and more effective practices; g. Develop a sense of interdependence and understanding towards each other; h. Recognize the gaps and make efforts to bridge them; i. -

Moving from a Monologue to a Dialogue

Moving from a Monologue to a Dialogue Brazilian by birth, Augusto Boal is a theatre director, writer and theorist, whose path-breaking book Theatre of the Oppressed which proposed ways of returning theatre to the people, has become a seminal text for theatre practitioners. Taking off from the work of Paolo Freire, his theatre techniques and games are now being used all over the world, including institutes of psychotherapy. In November 1991, the International Association of Theatre of the Oppressed was formed. The Indian cultural organization Jana Sanskriti, which for several years has been using Boal's ideas and methods in its own grassroots theatre work in rural Bengal, is a member. Early this year, Boal was in Calcutta for a workshop organized by this group. Theatre has a long tradition of being a medium for political intervention-a forum for criticism, analysis, satire, debate, revolutionary rhetoric, suggestions for change. Within India this tradition has always been strong, a parallel stream alongside the 'theatre as entertainment' or 'theatre as art for art's sake' schools of thought. We have several active people's theatre groups functioning at the urban, semi-urban and rural levels. These groups usually work outside the proscenium, with a kind of theatre that eschews the baggage and technology of stages, sets, lights, and elaborate costumes. Poor theatre, Alternative theatre, People's theatre, Third theatre are some of the terms used to categorize such activity, which uses human bodies and flexibility as its basic organizing principle. Call it by whichever name you like, it is theatre for change-social, cultural, economic, political. -

Chapter Preview

2 Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel 1 An Eventful Life he iron man of India, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (31 October 1875 - 15 December 1950) was a political and social Tleader of India who played a major role in the country’s struggle for independence and guided its integration into a united, independent nation. He was called as “Iron Man of India” In India and across the world, he was often addressed as Sardar, which means Chief in many languages of India. Raised in the countryside of Gujarat in Gurjar community and largely self-educated, Vallabhbhai Patel was employed in successful practice as a lawyer when he was first inspired by the work and philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. Patel subsequently organised the peasants of Kheda, Borsad, and Bardoli in Gujarat in non-violent civil disobedience against oppressive policies imposed by the British Raj; in this role, he became one of the most influential leaders in Gujarat. He rose to the leadership of the Indian National Congress and was at the forefront of rebellions and political events, organising the party for elections in 1934 and 1937, and promoting the Quit India movement. As the first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister of India, Patel organised relief for refugees in Punjab and Delhi, and led efforts to restore peace across the nation. Patel took charge of the task to forge a united India from the 565 semi-autonomous An Eventful Life 3 princely states and British-era colonial provinces. Using frank diplomacy backed with the option (and the use) of military action, Patel’s leadership enabled the accession of almost every princely state.